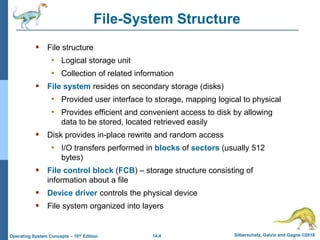

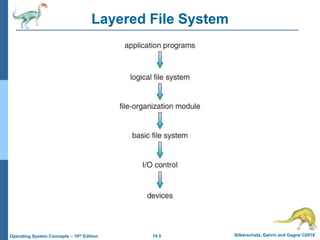

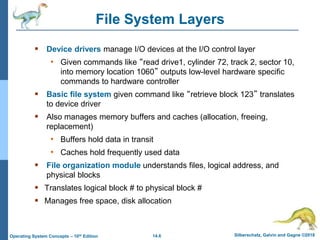

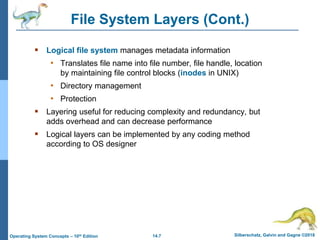

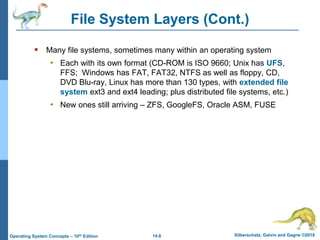

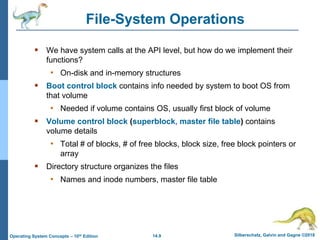

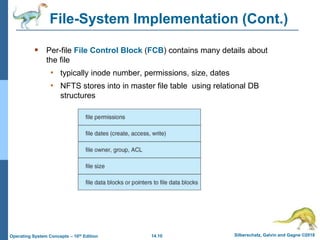

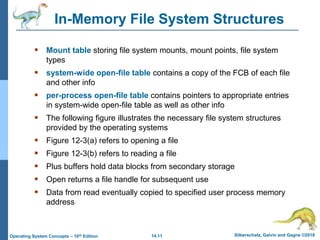

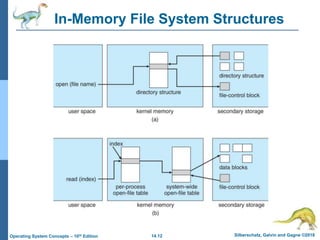

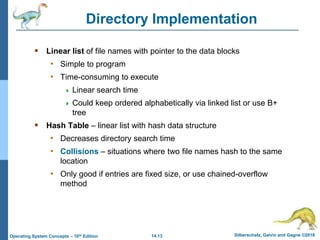

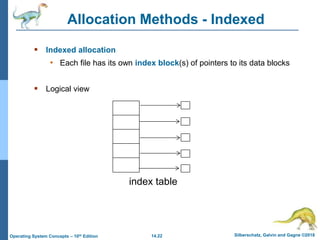

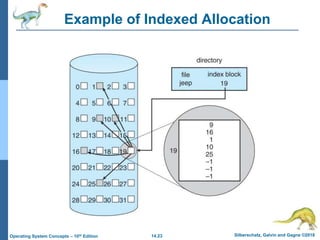

This document provides an overview of file system implementation and concepts. It describes the layered structure of a typical file system, with different layers managing devices, basic file system functions, logical file system metadata, and the user interface. Common file system data structures are discussed, including file control blocks, directories implemented as lists or hash tables, and allocation methods like contiguous, linked, indexed, and extent-based allocation. The document also covers in-memory file system structures, free space management using bitmaps or linked lists, techniques for improving efficiency and performance, and recovery through logging file system updates.

![14.31 Silberschatz, Galvin and Gagne ©2018

Operating System Concepts – 10th Edition

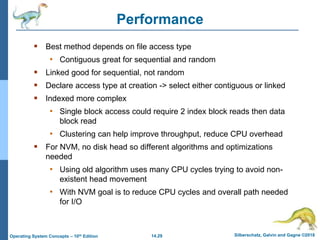

Free-Space Management

File system maintains free-space list to track available

blocks/clusters

• (Using term “block” for simplicity)

Bit vector or bit map (n blocks)

…

0 1 2 n-1

bit[i] =

1 block[i] free

0 block[i] occupied

Block number calculation

(number of bits per word) *

(number of 0-value words) +

offset of first 1 bit

CPUs have instructions to return offset within word of first “1” bit](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ch14-220108181203/85/Chapter-14-Computer-Architecture-25-320.jpg)