Chapter 11 of 'Finance by Boundless' covers capital budgeting, which is the planning process to determine long-term investments worth pursuing. Key methods include net present value (NPV), internal rate of return (IRR), payback period, and profitability index, all of which help to rank and evaluate investment proposals. The chapter emphasizes the importance of accurate forecasting of revenues and expenditures and outlines that capital budgeting plays a crucial role in the financial health and direction of an organization.

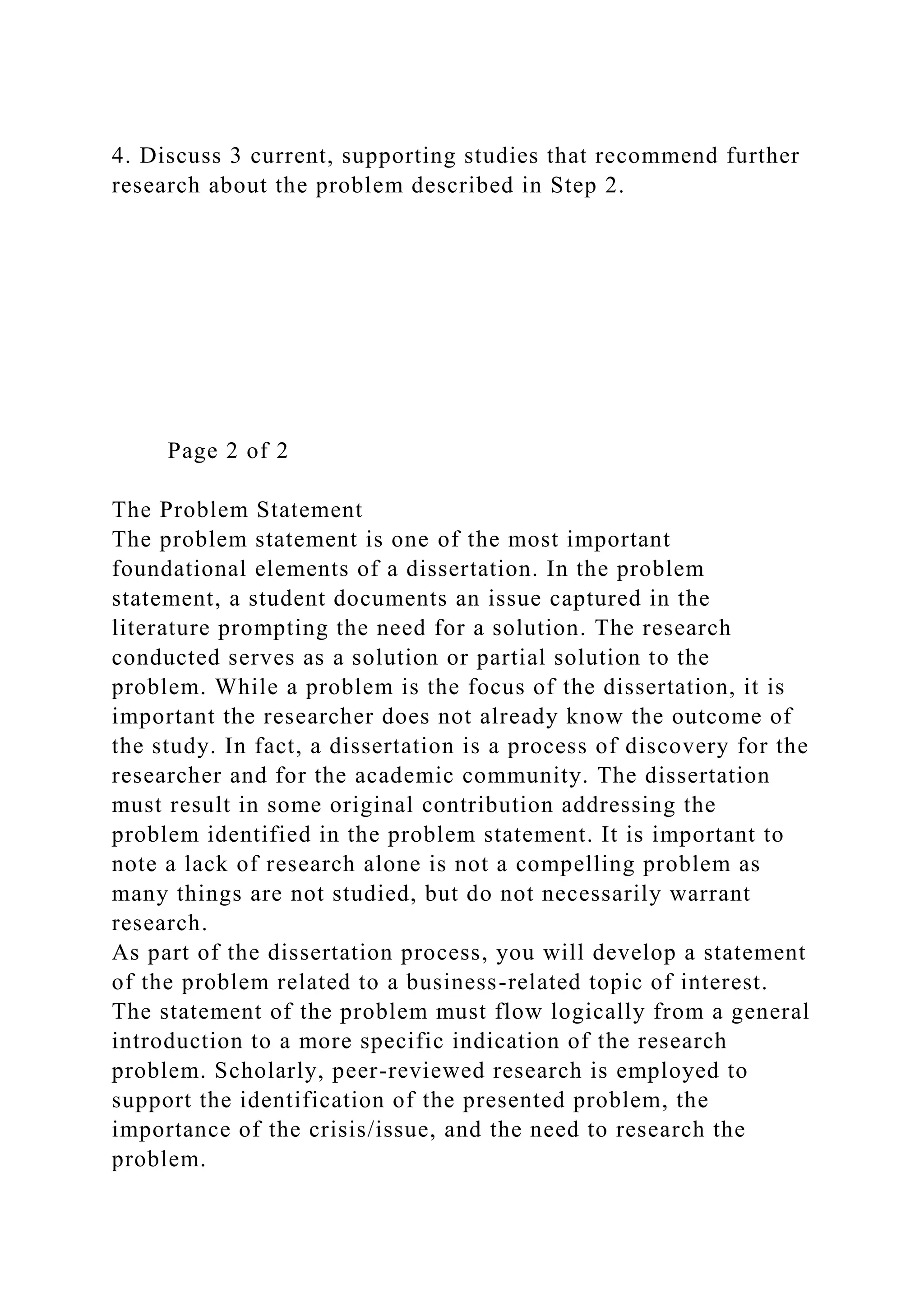

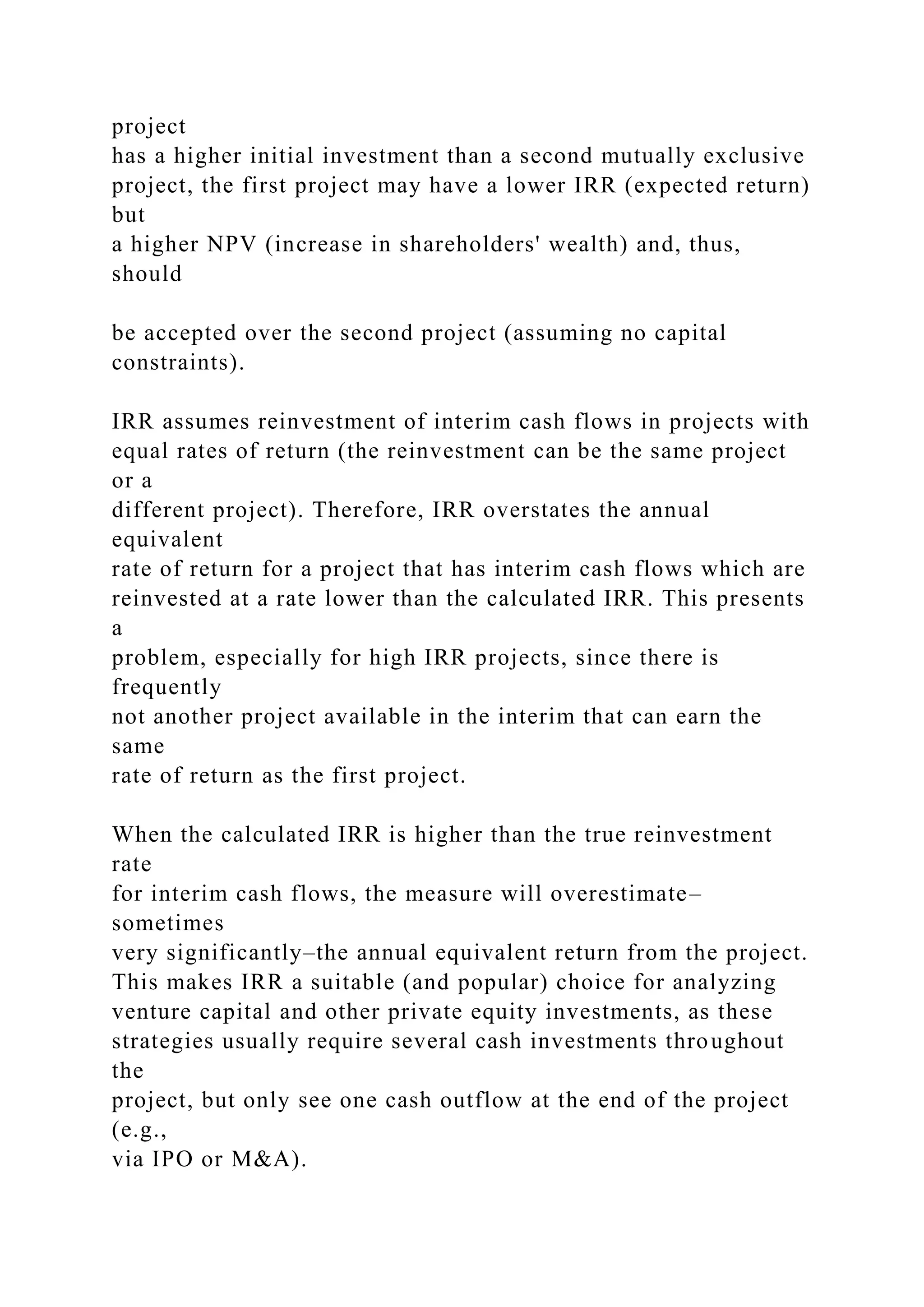

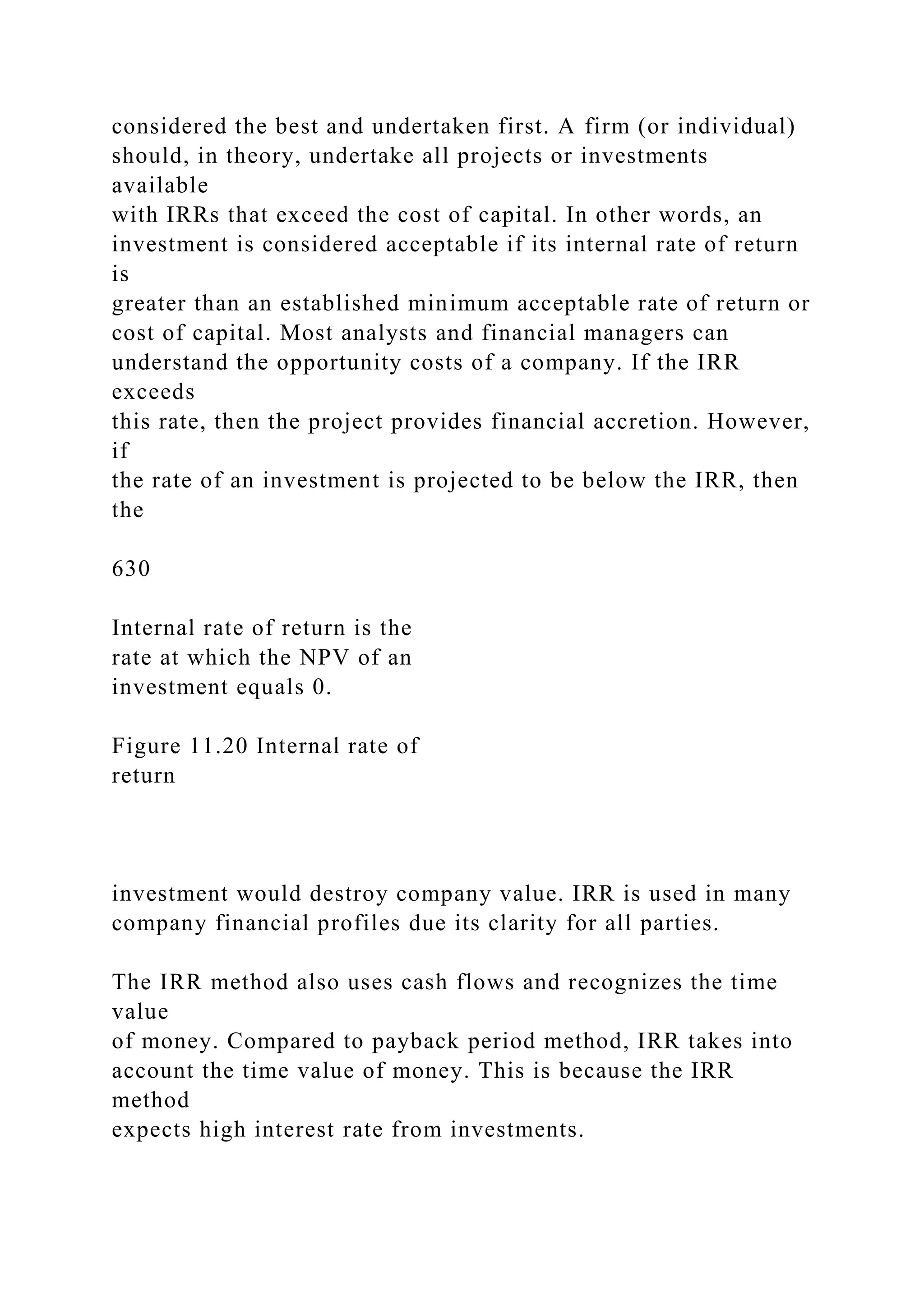

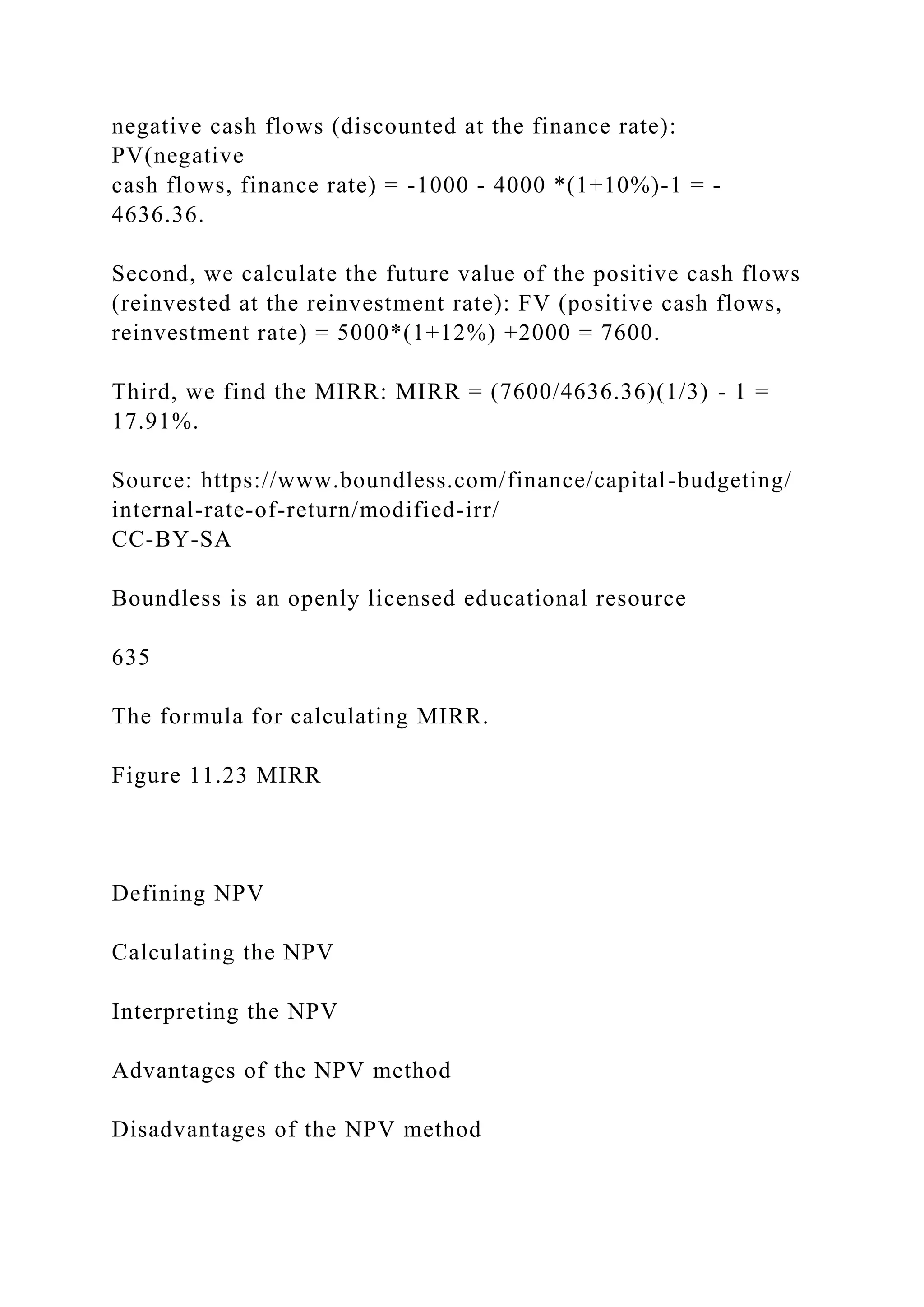

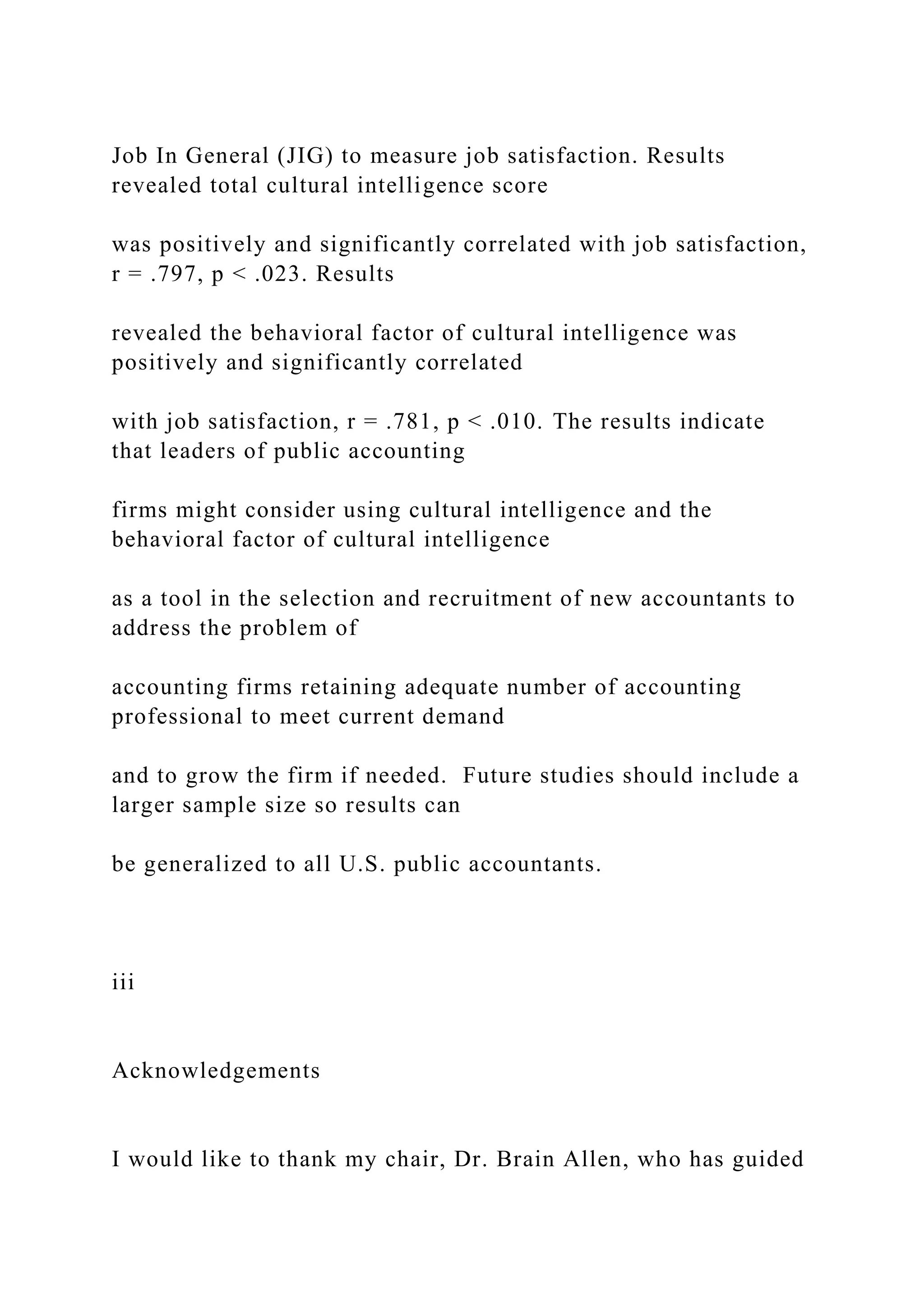

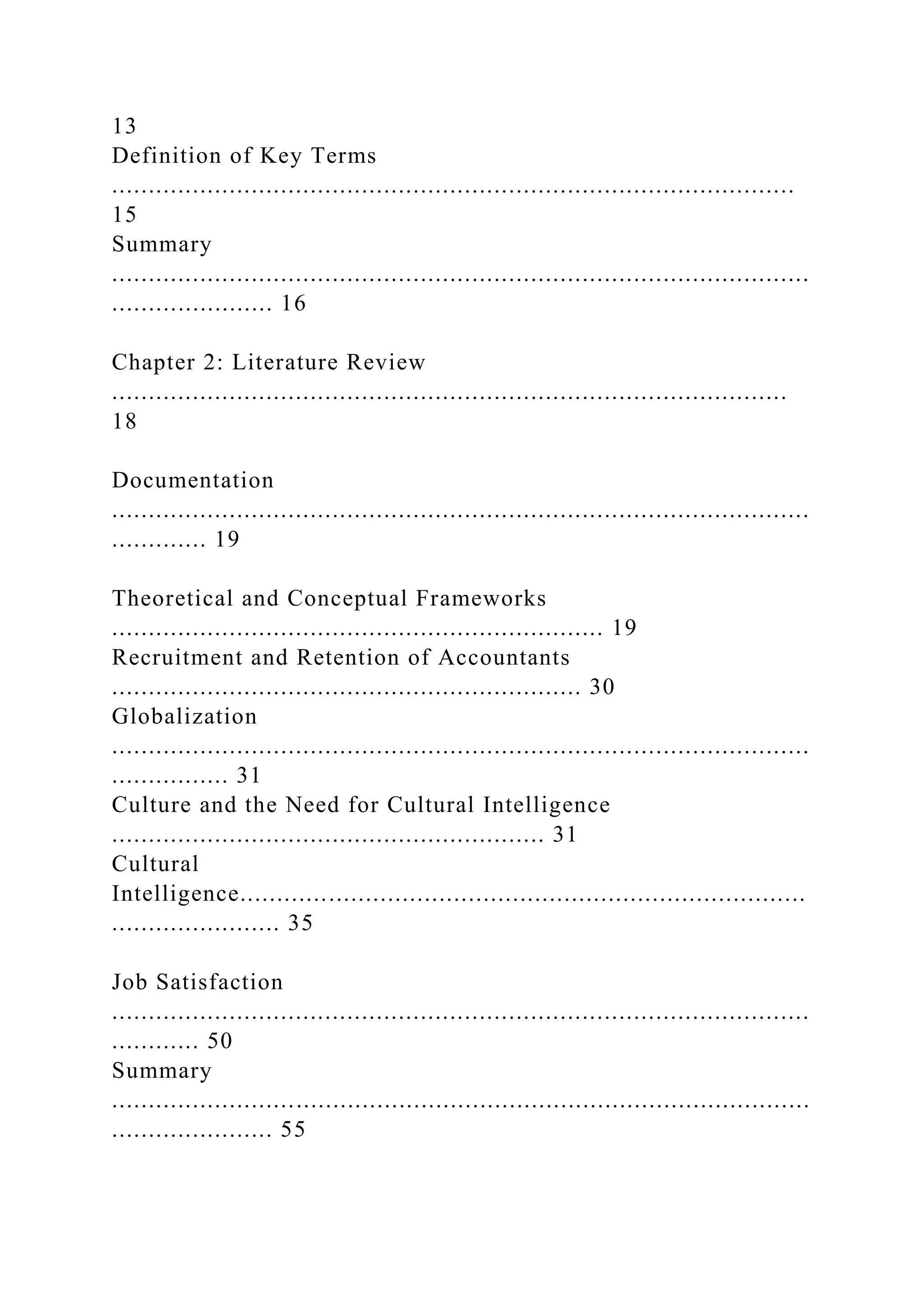

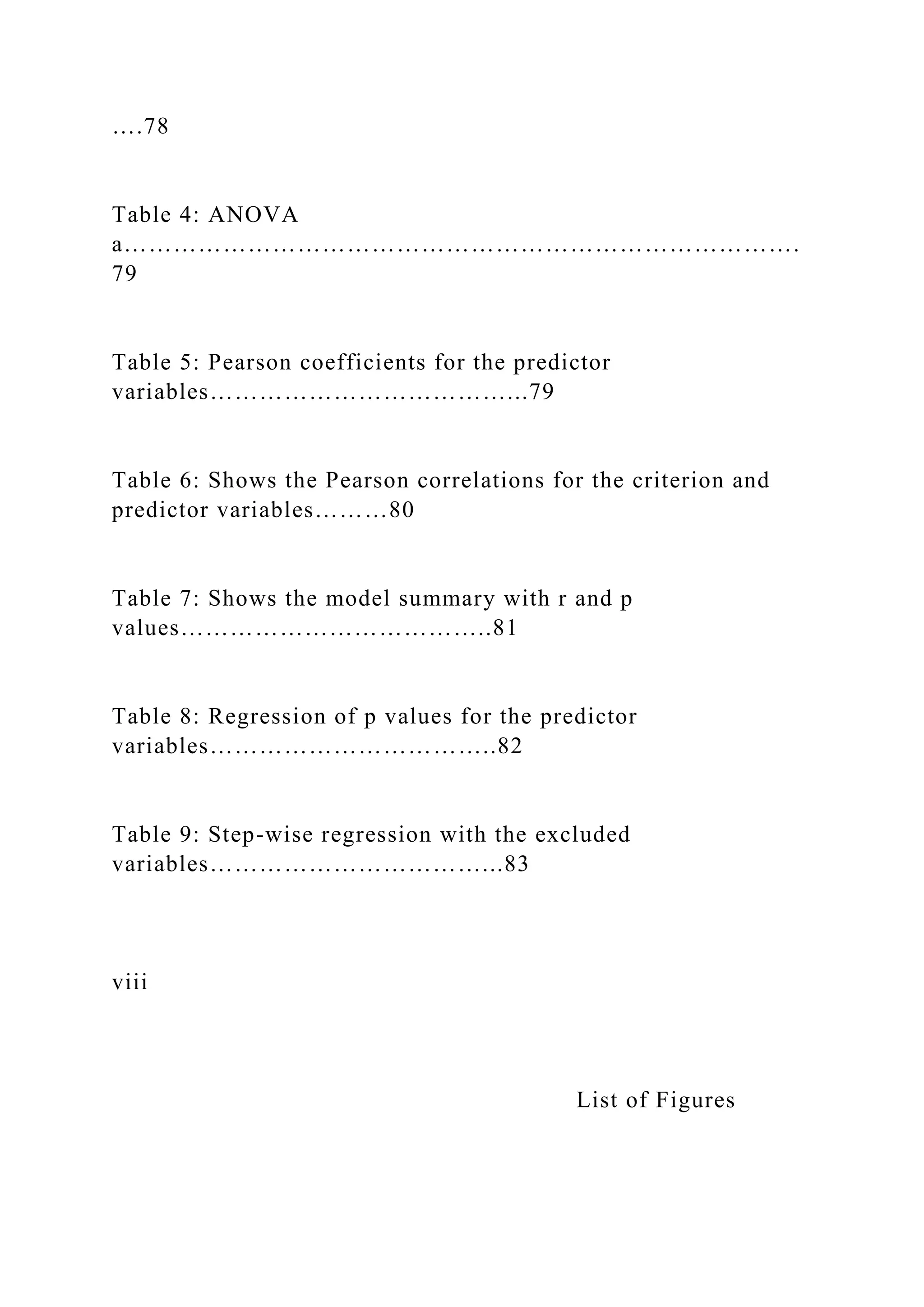

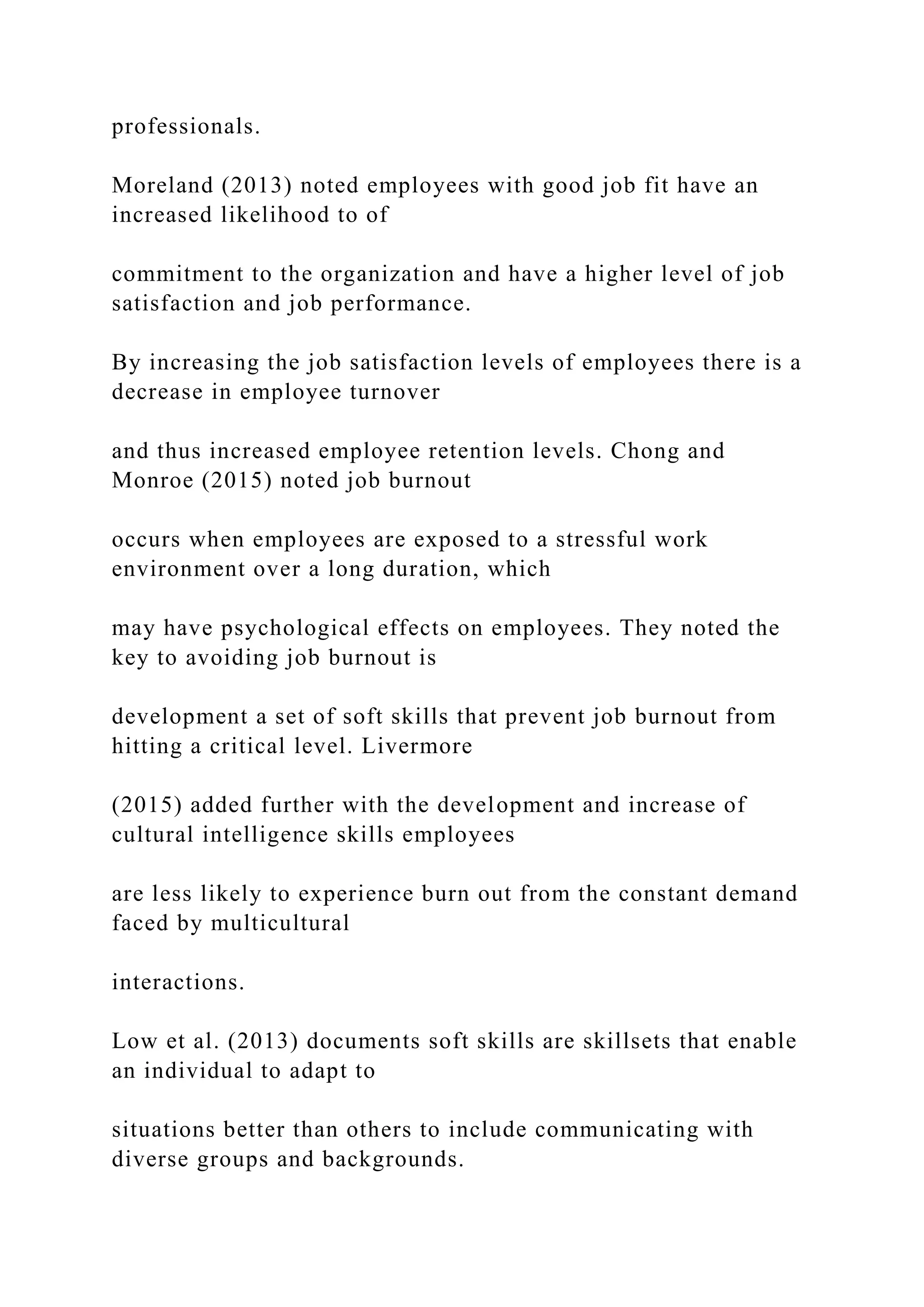

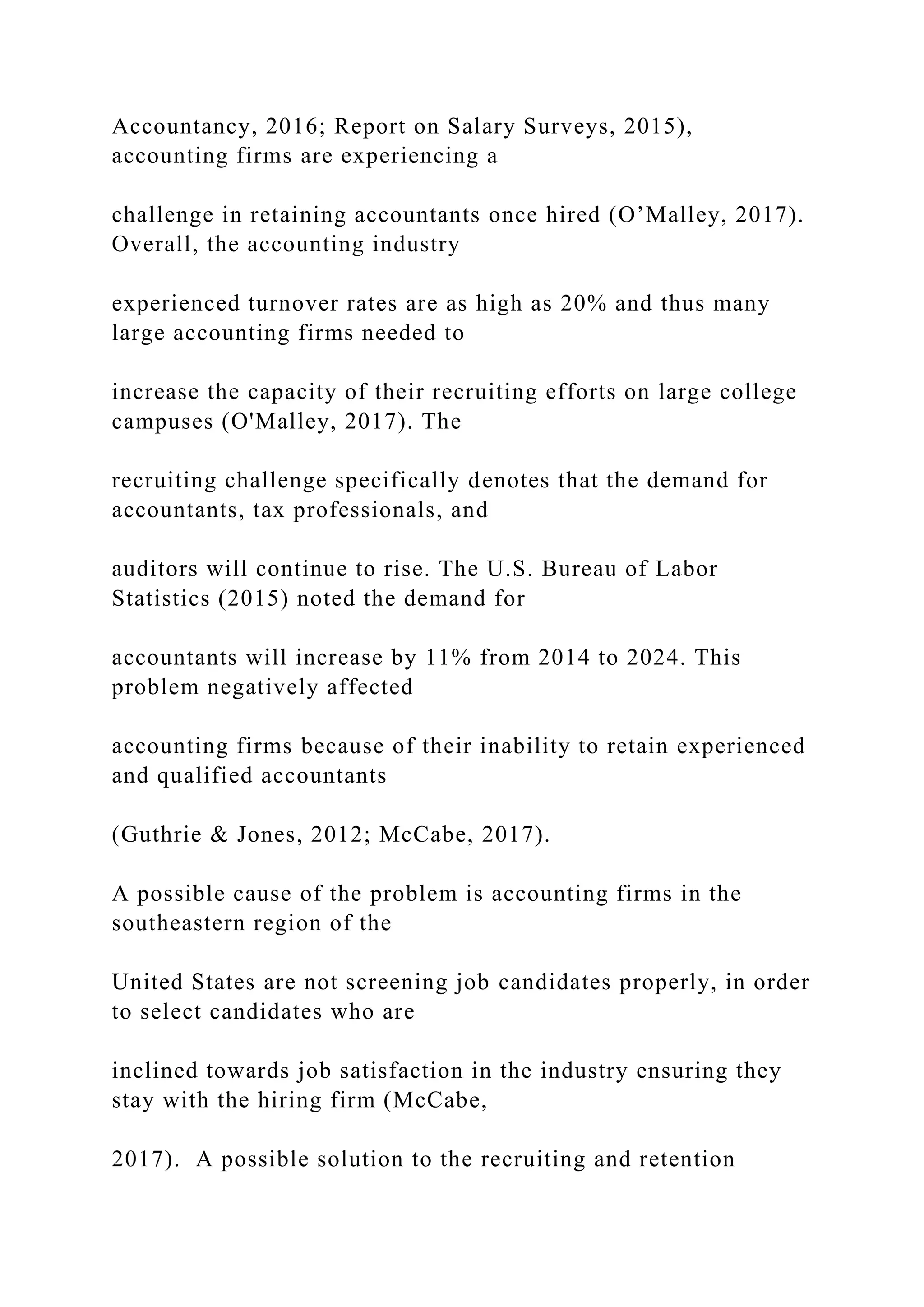

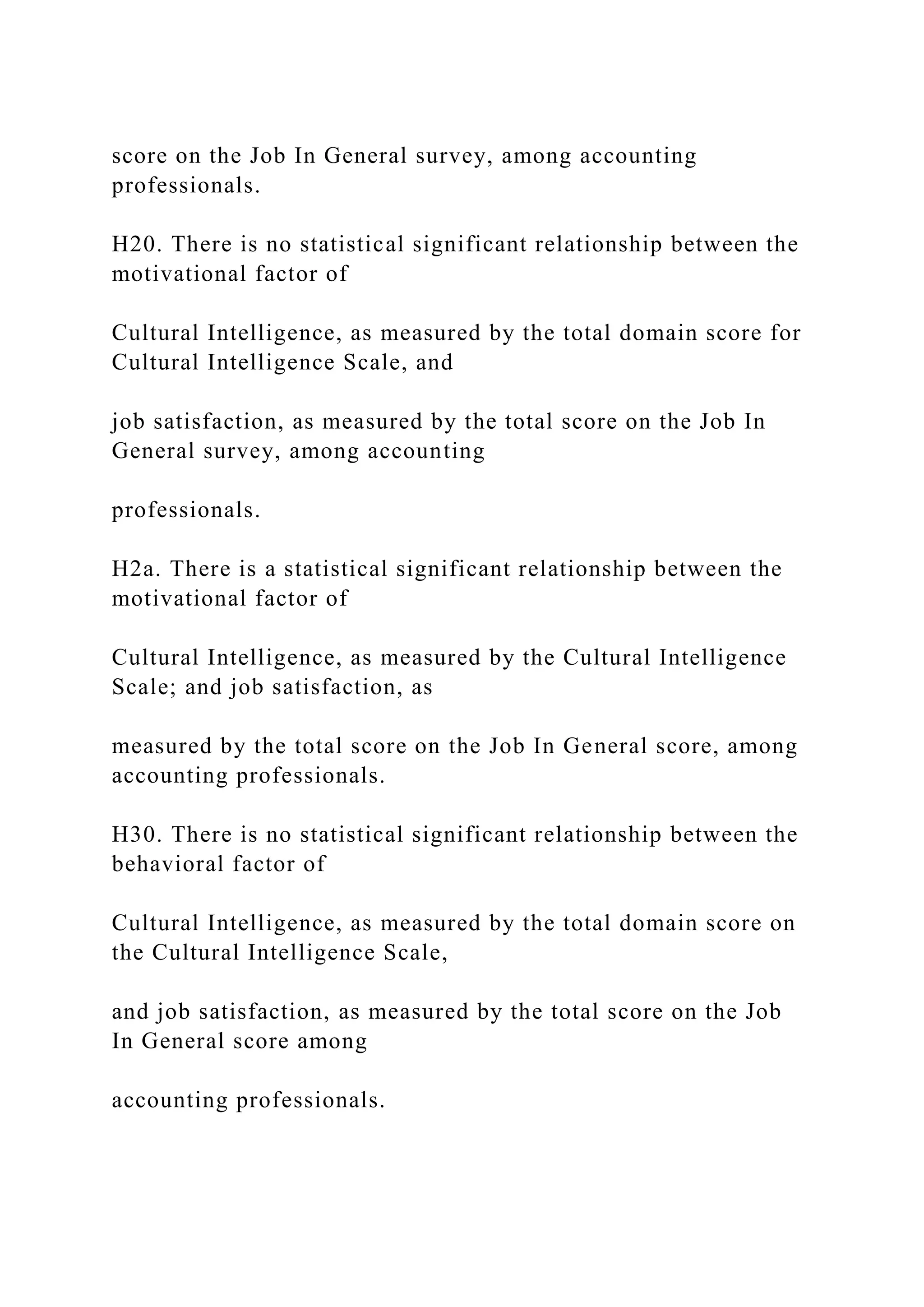

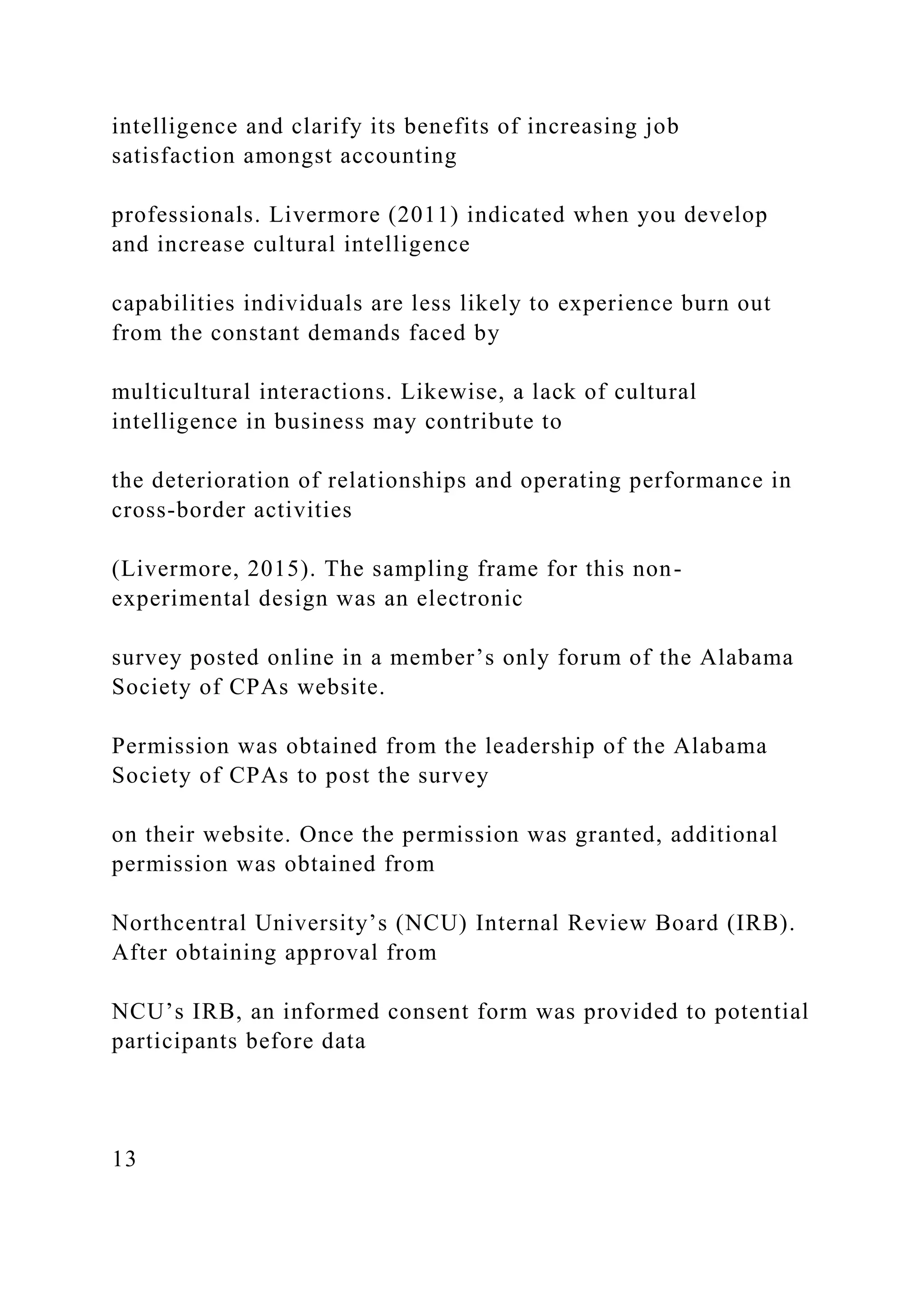

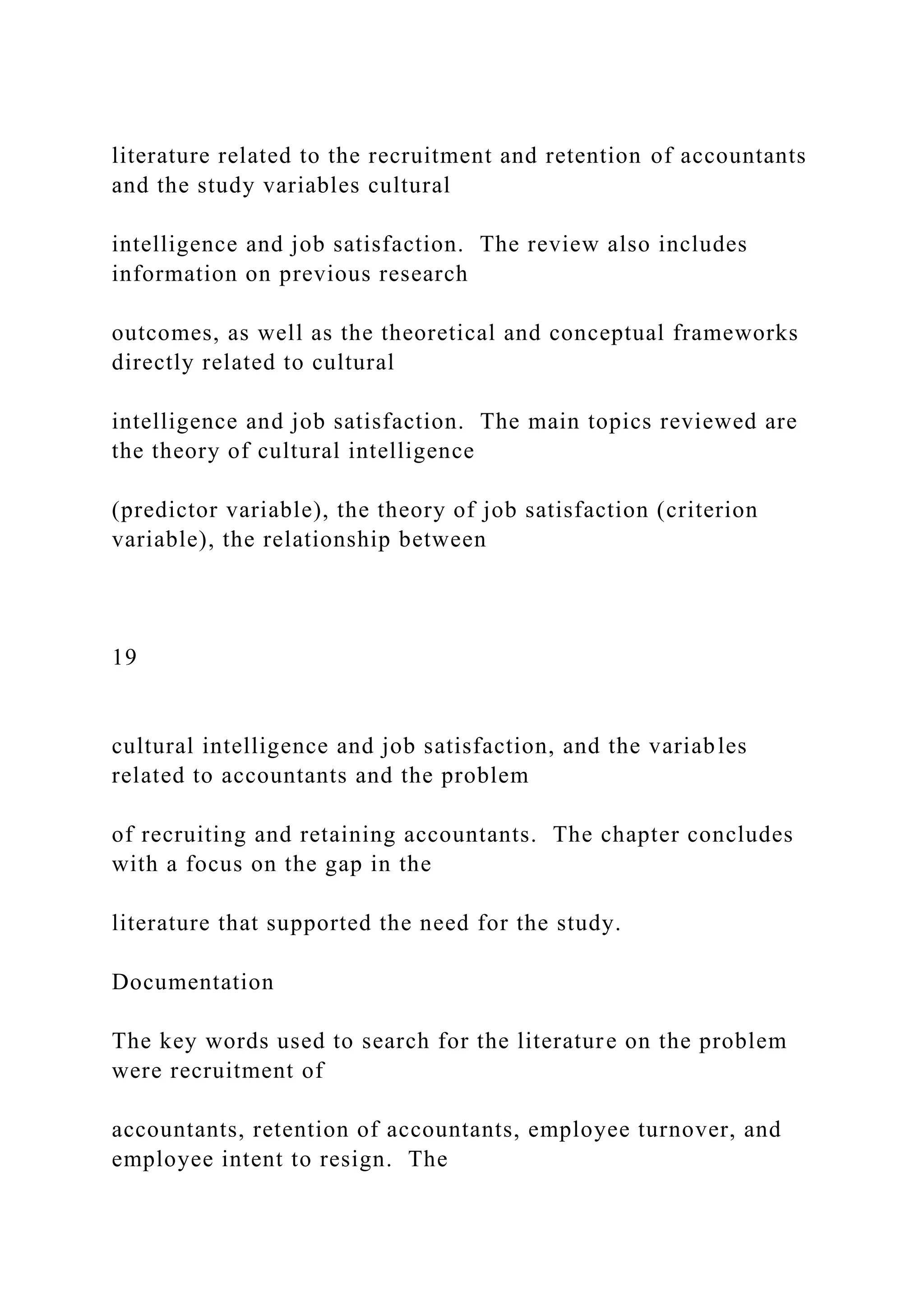

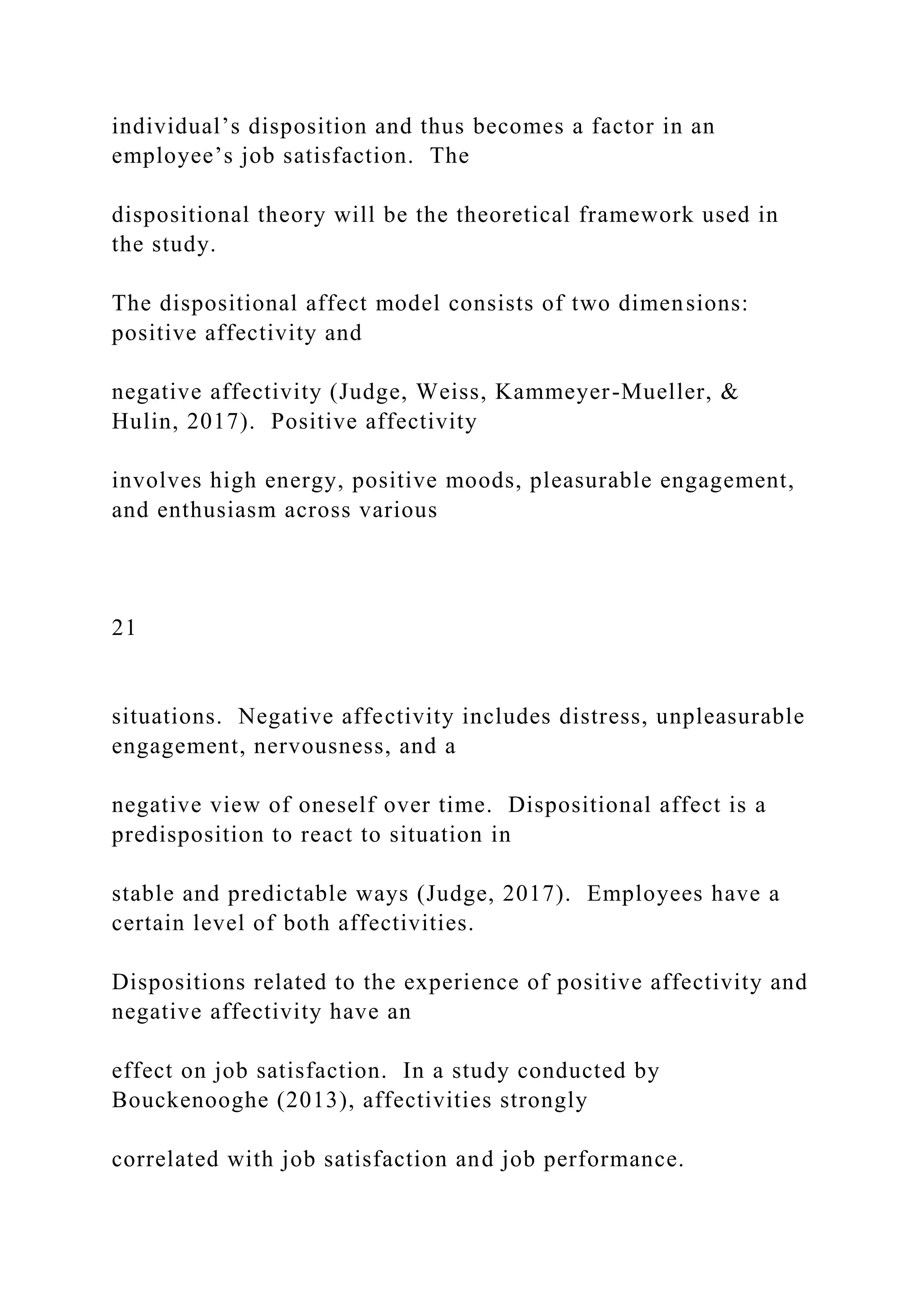

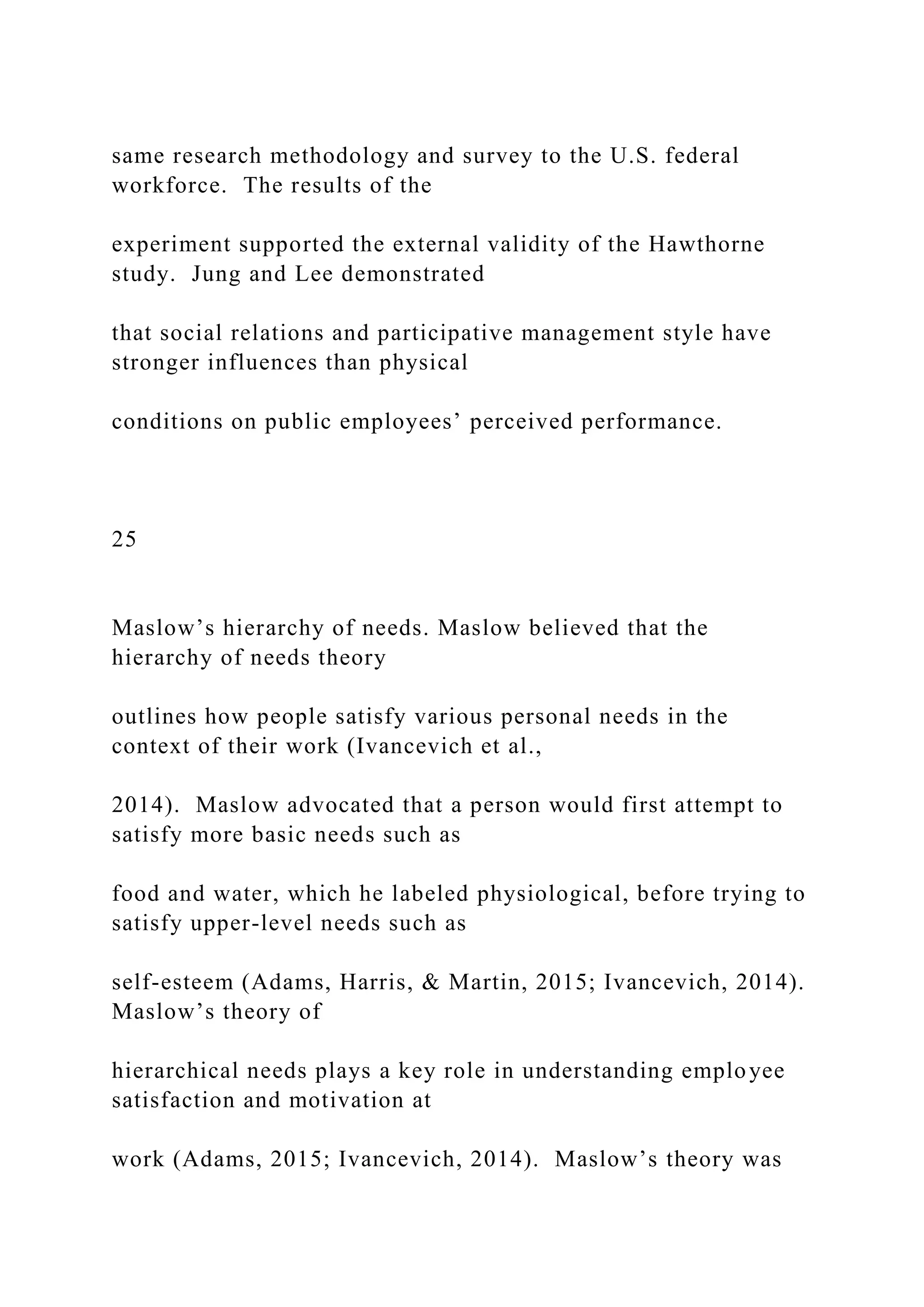

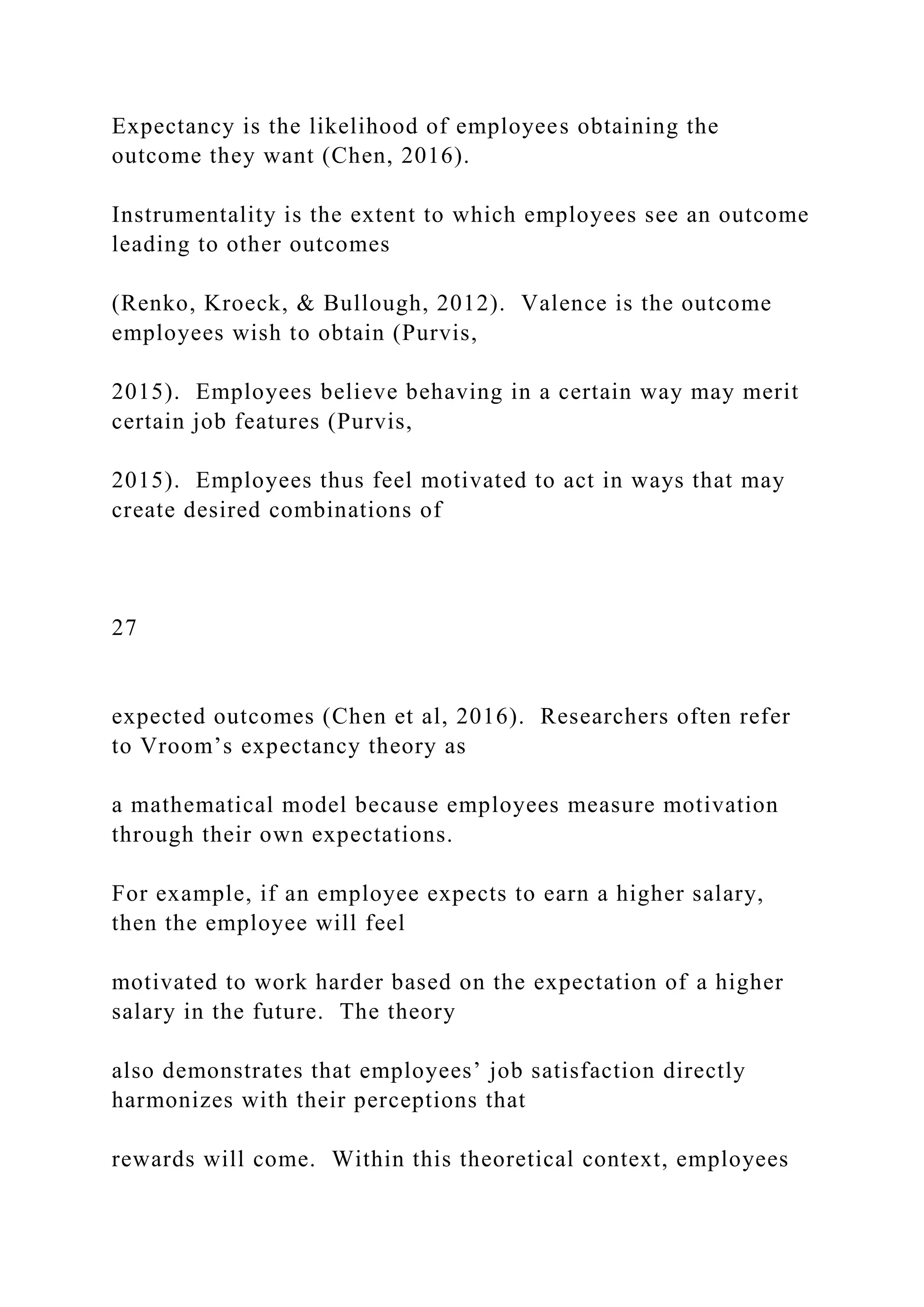

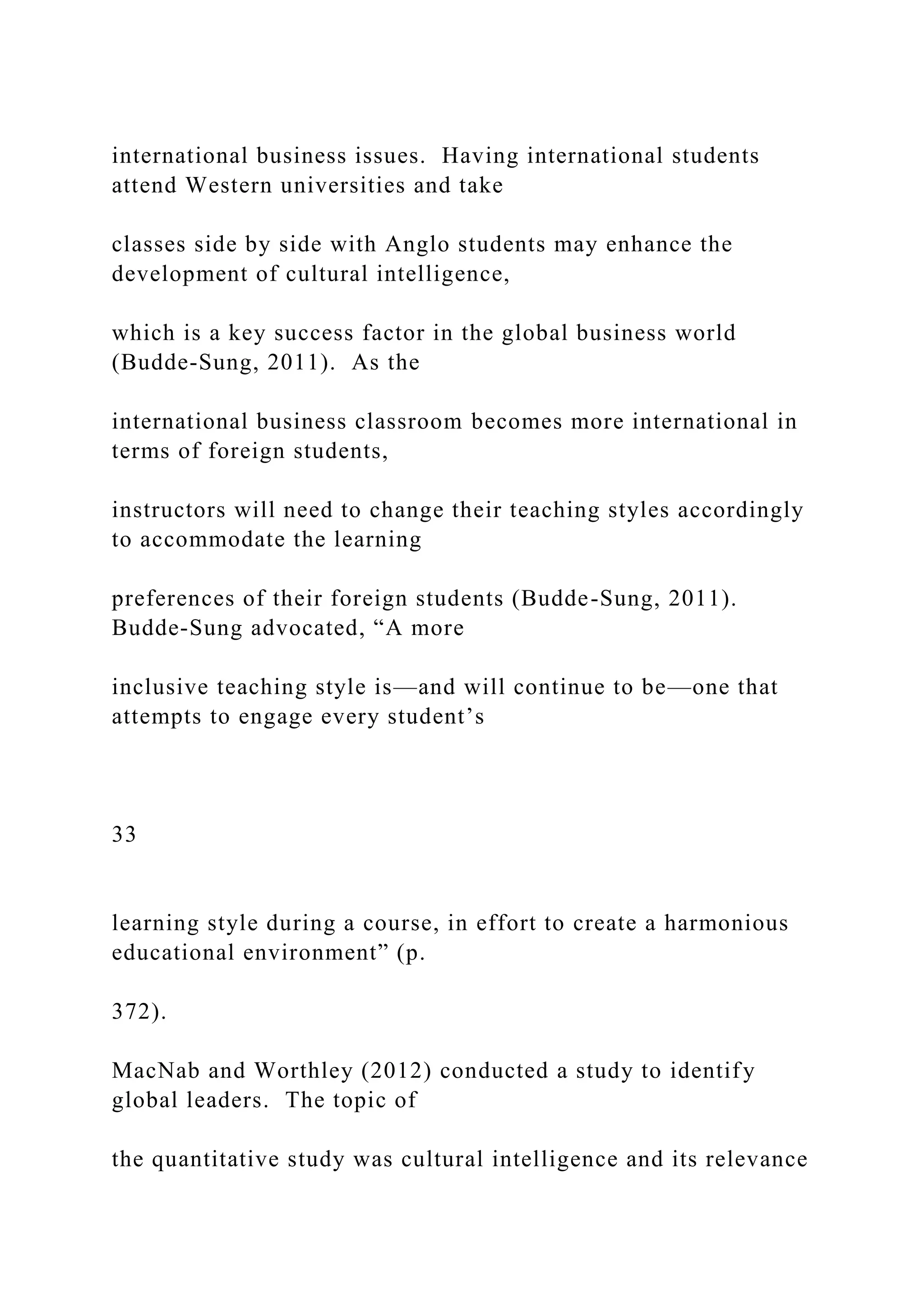

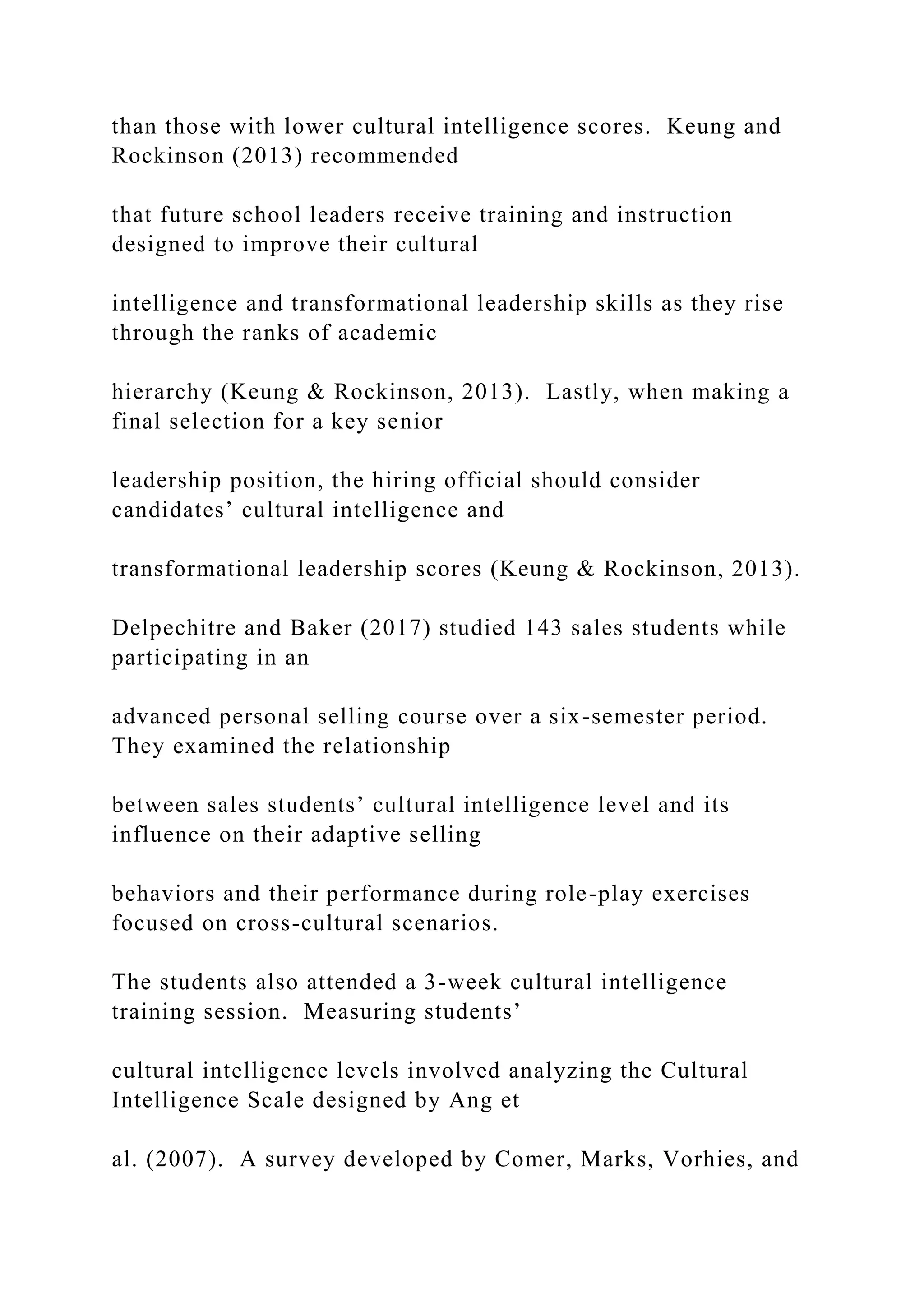

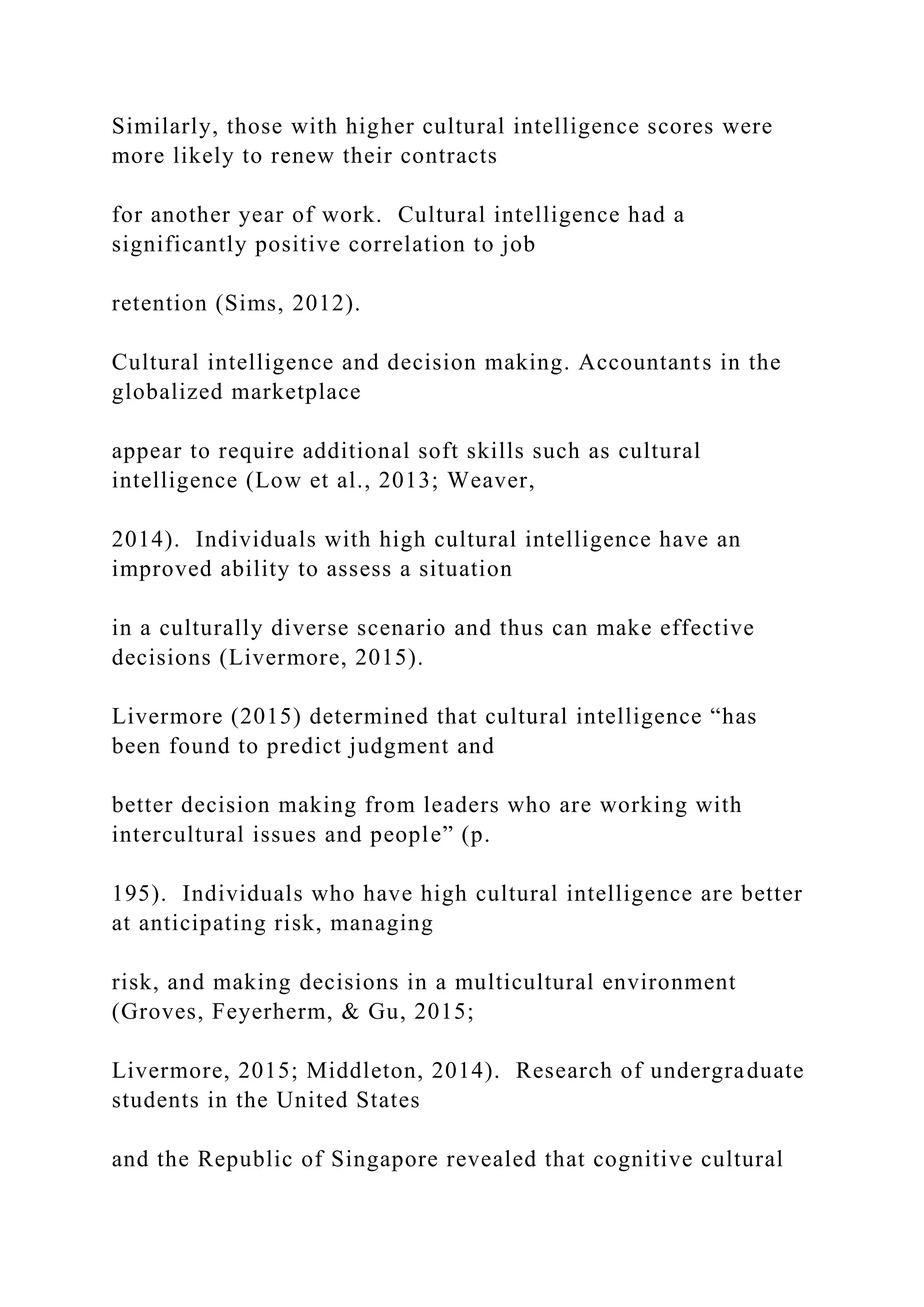

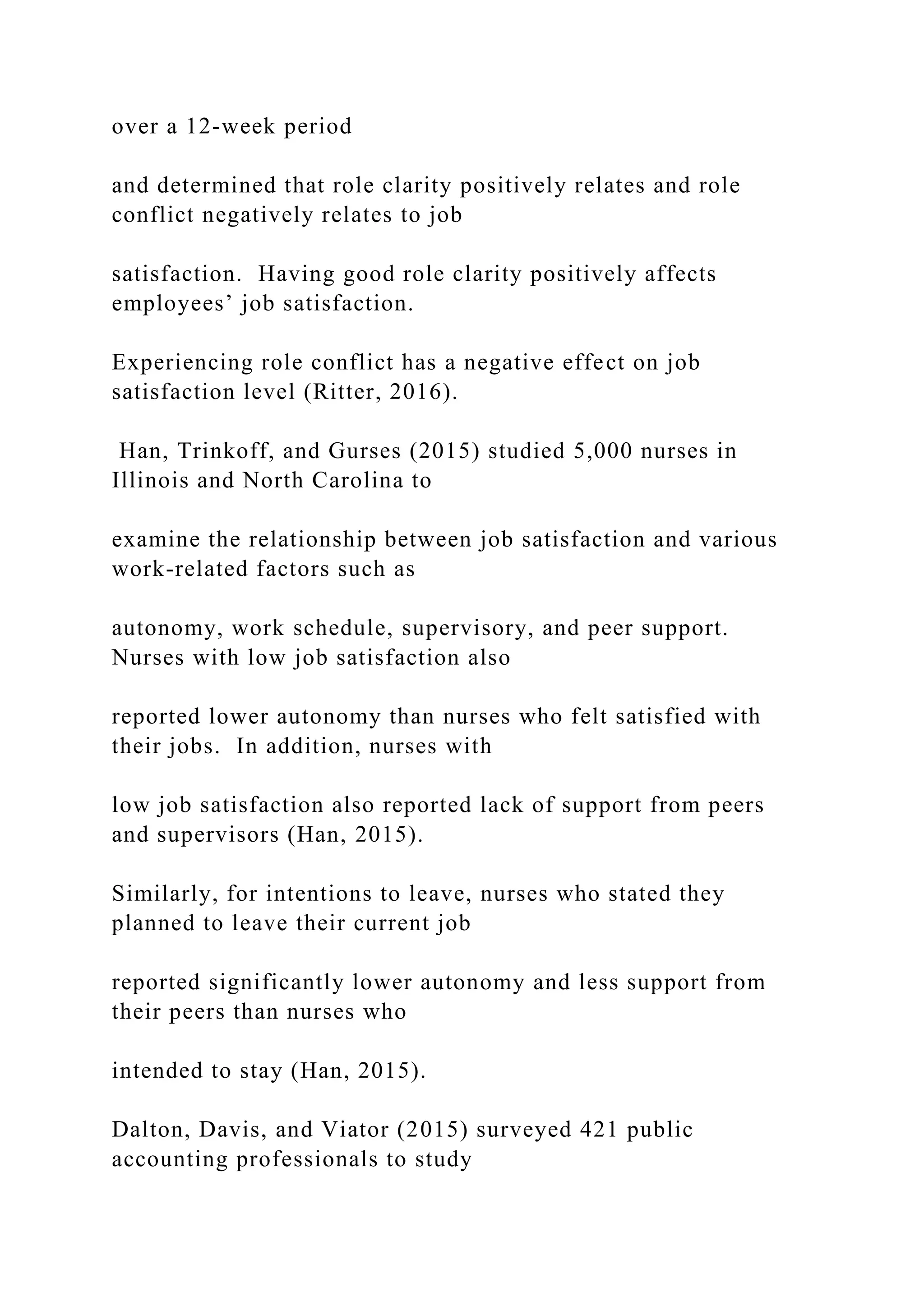

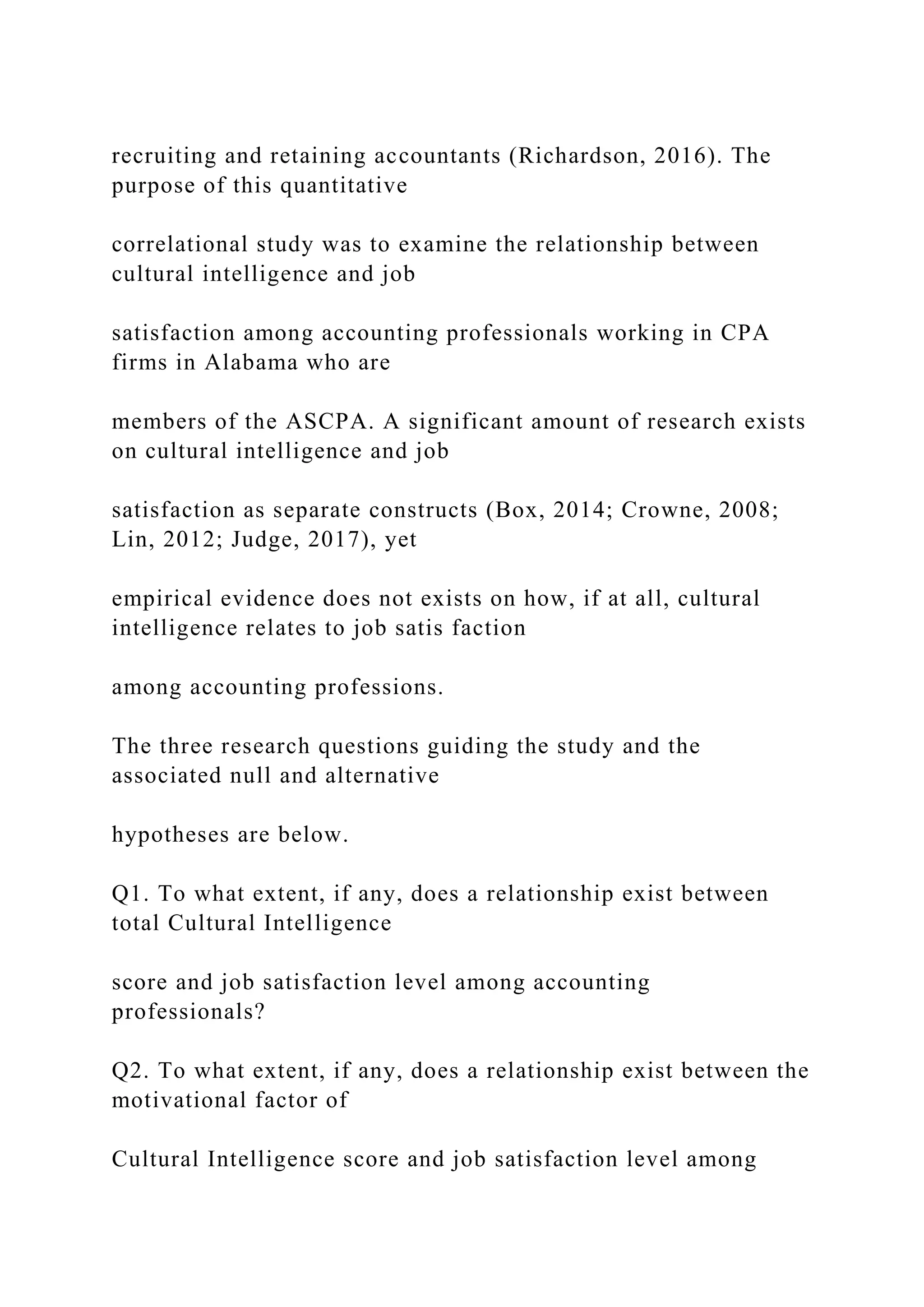

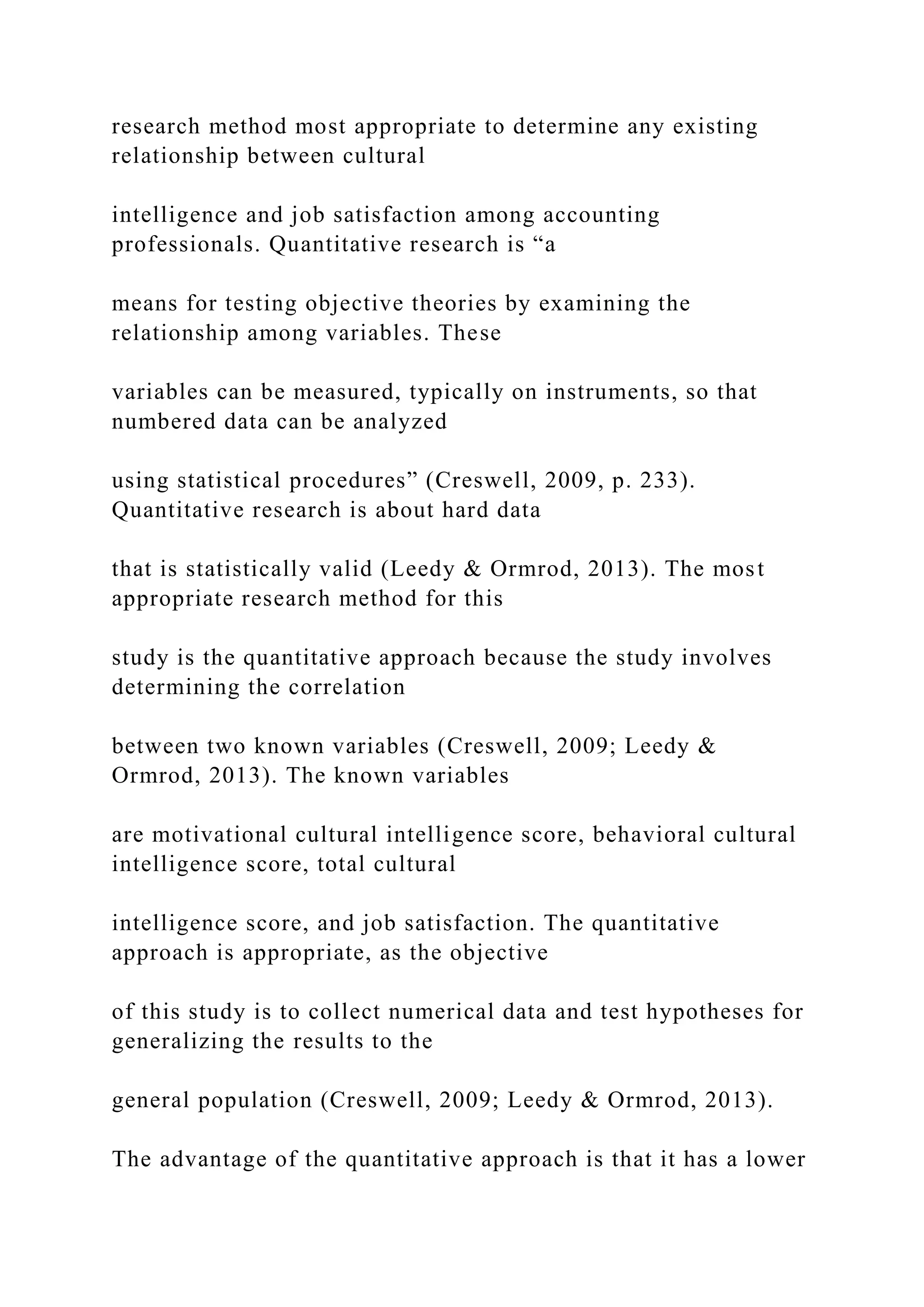

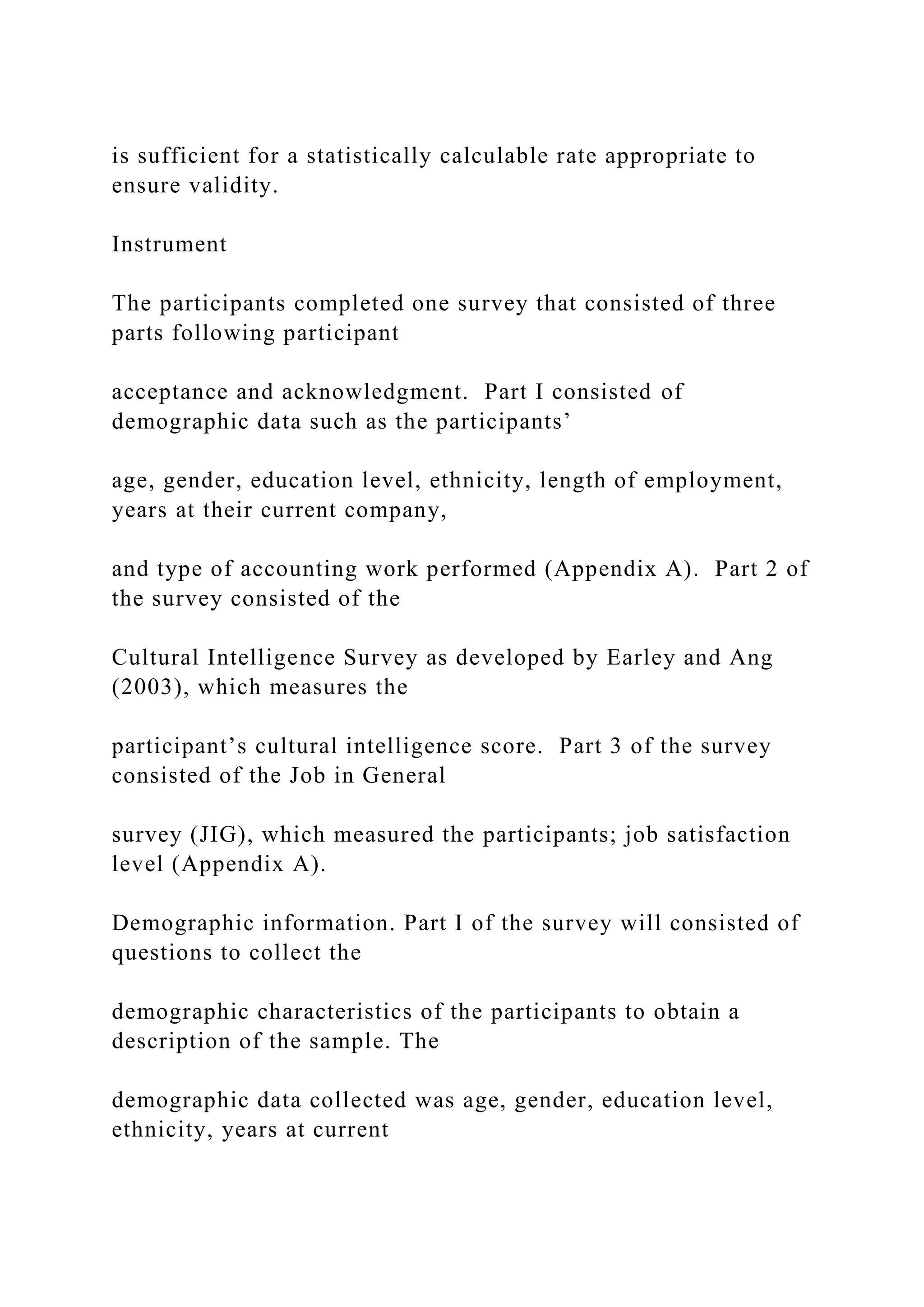

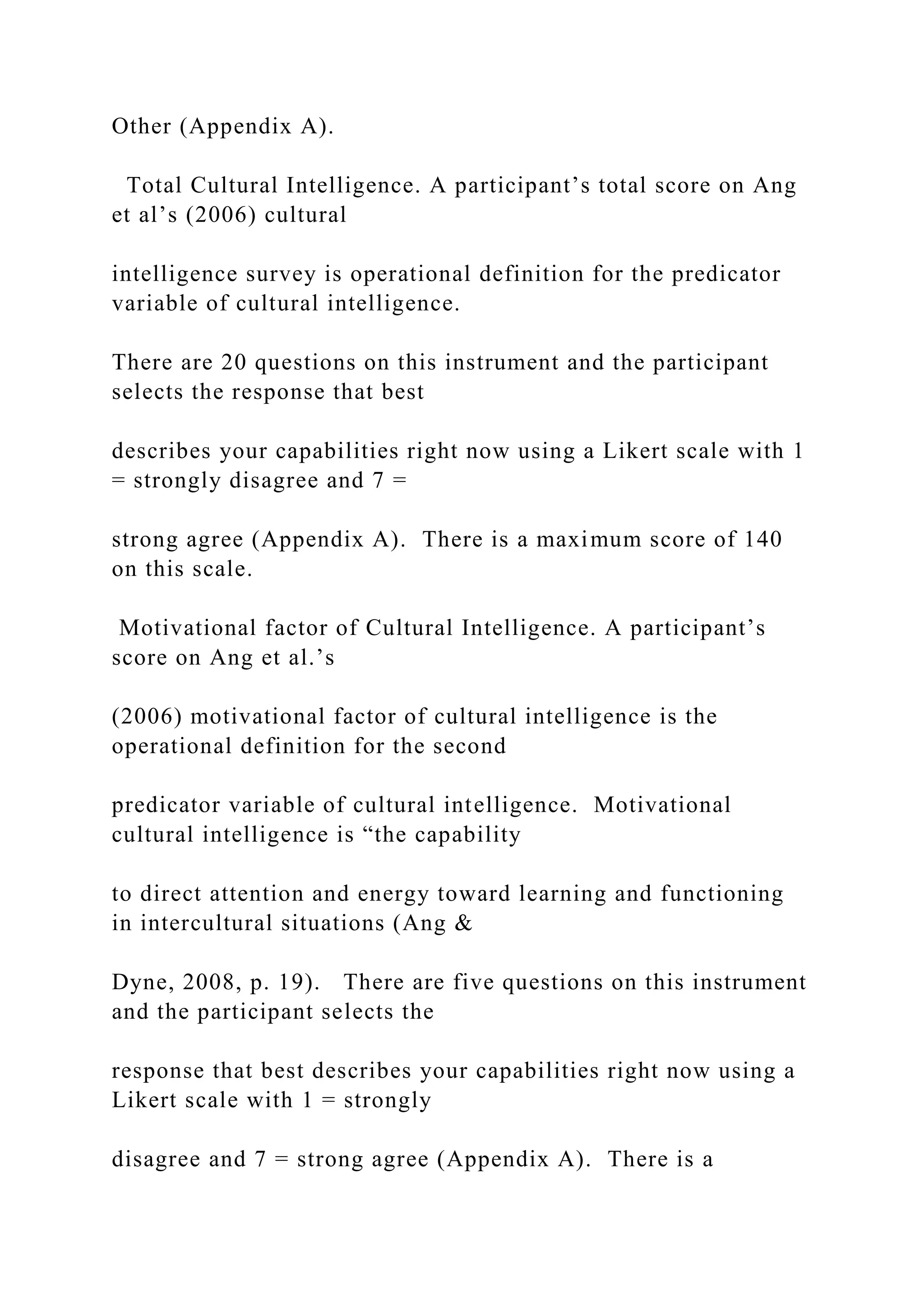

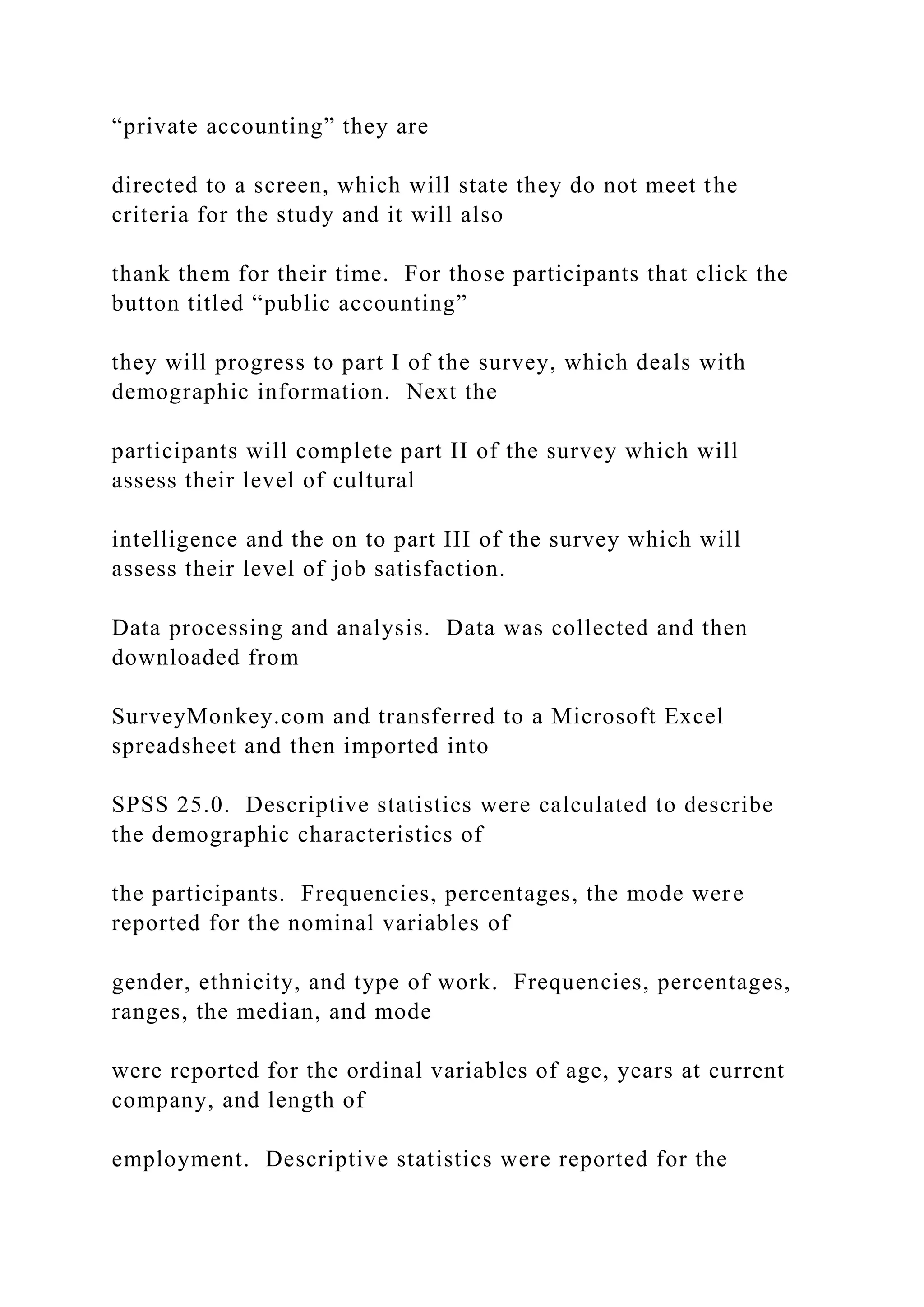

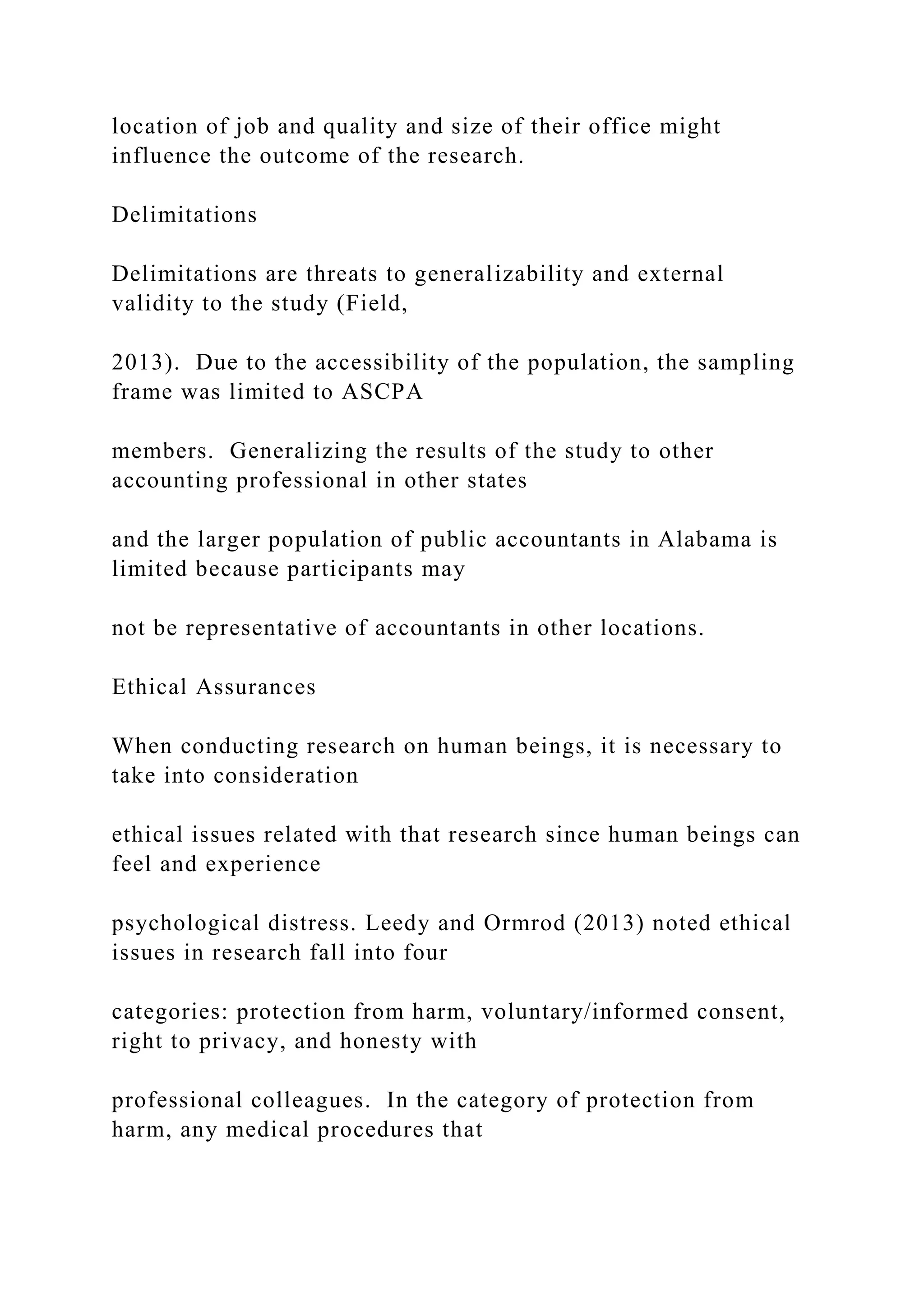

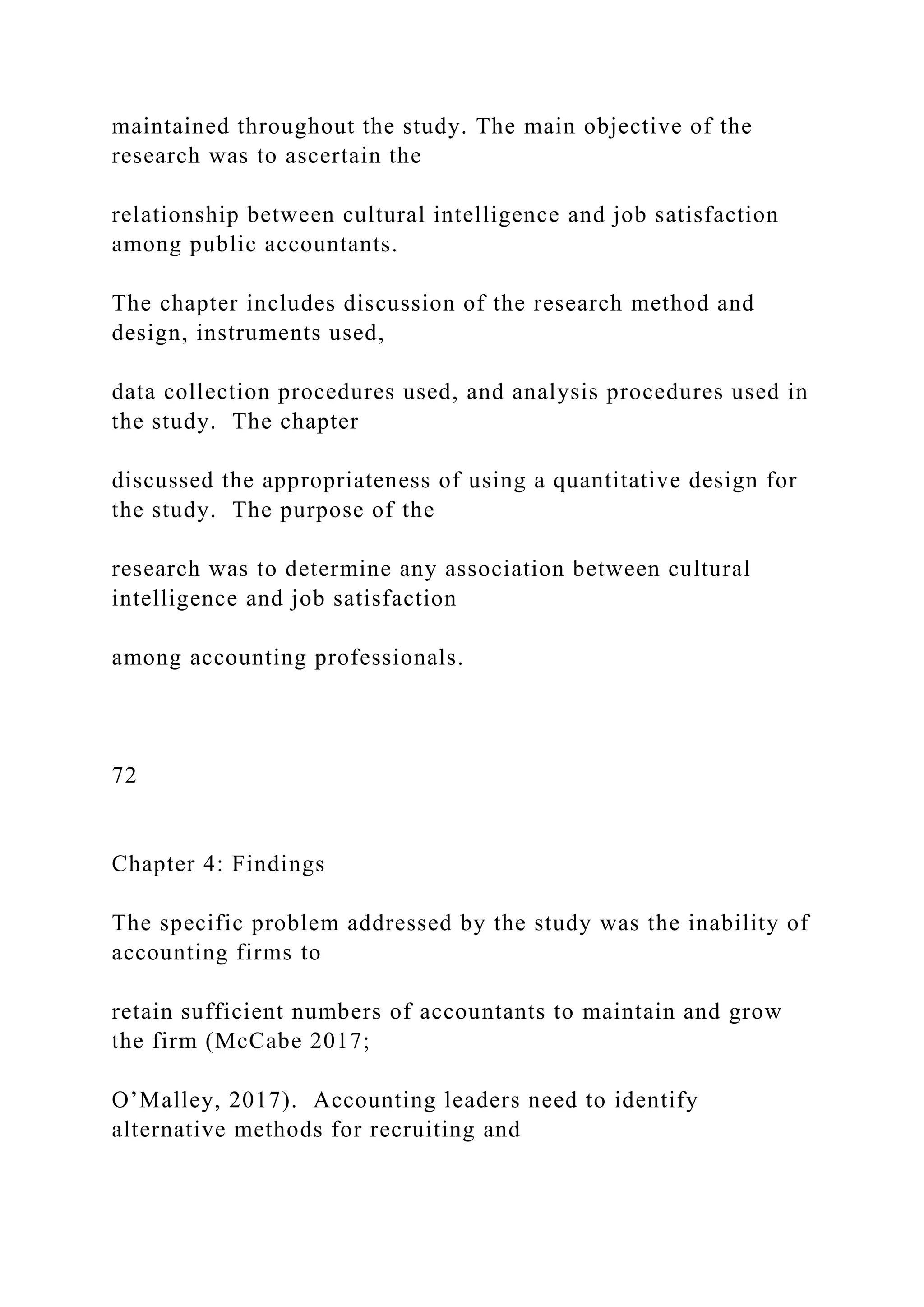

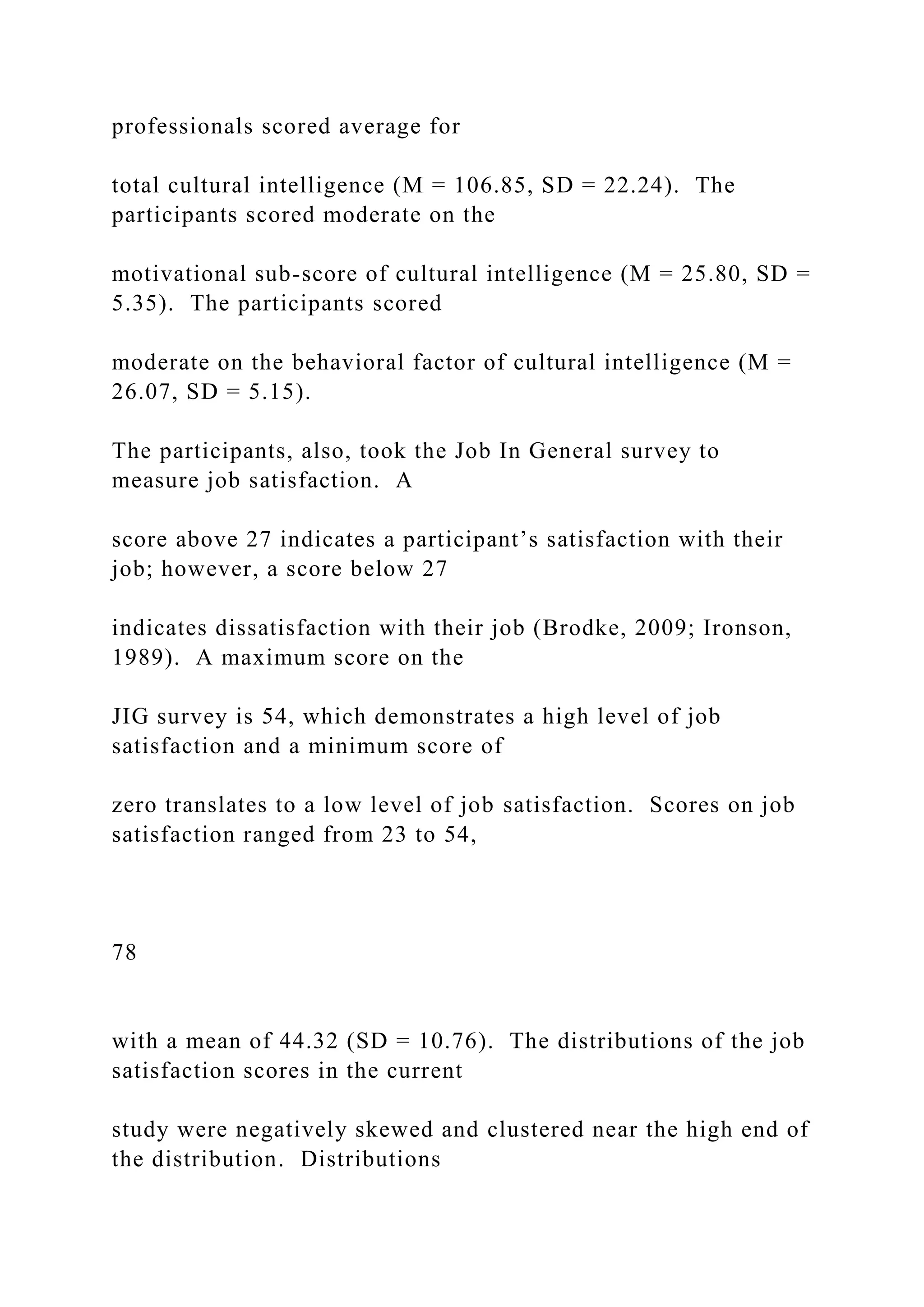

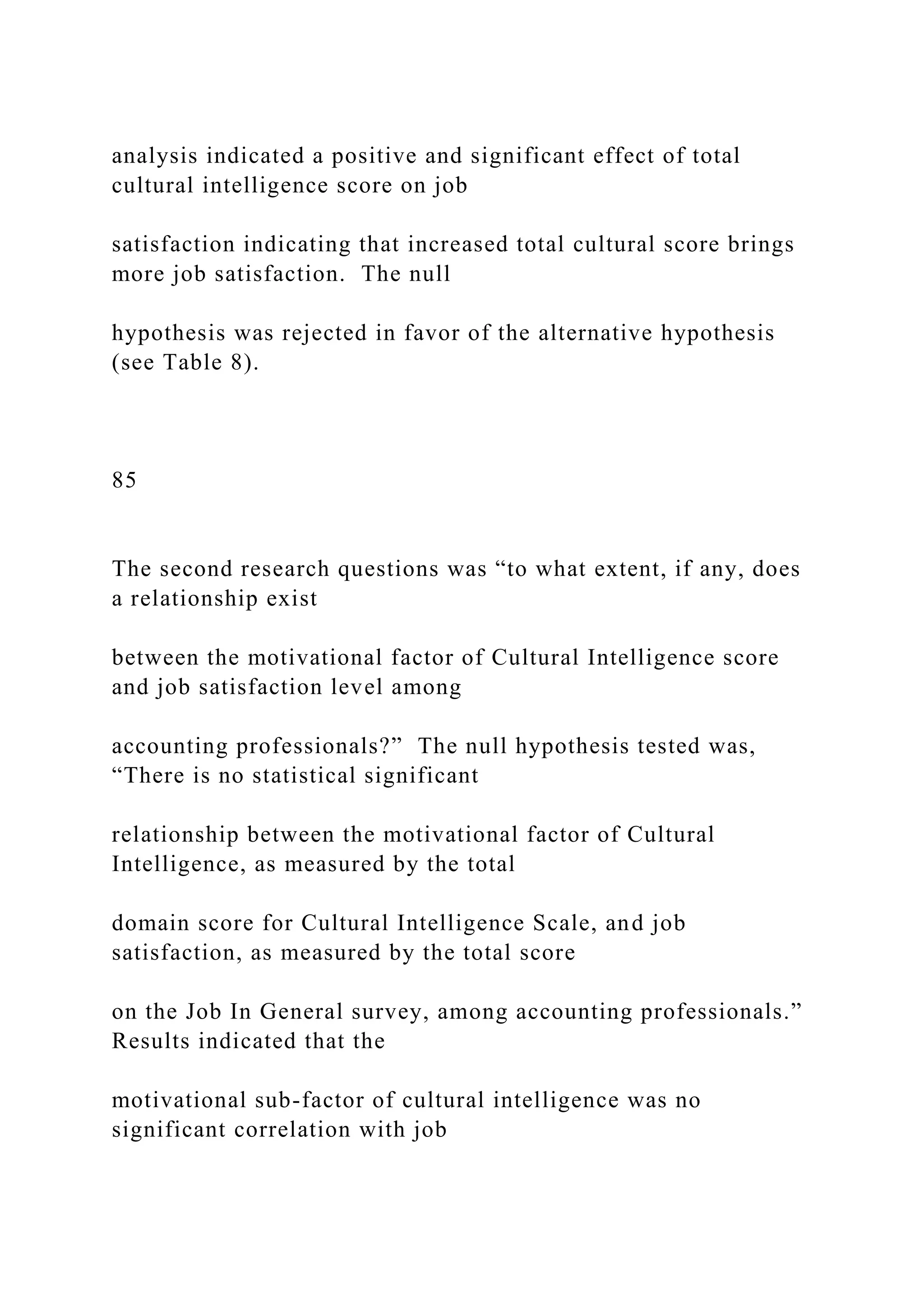

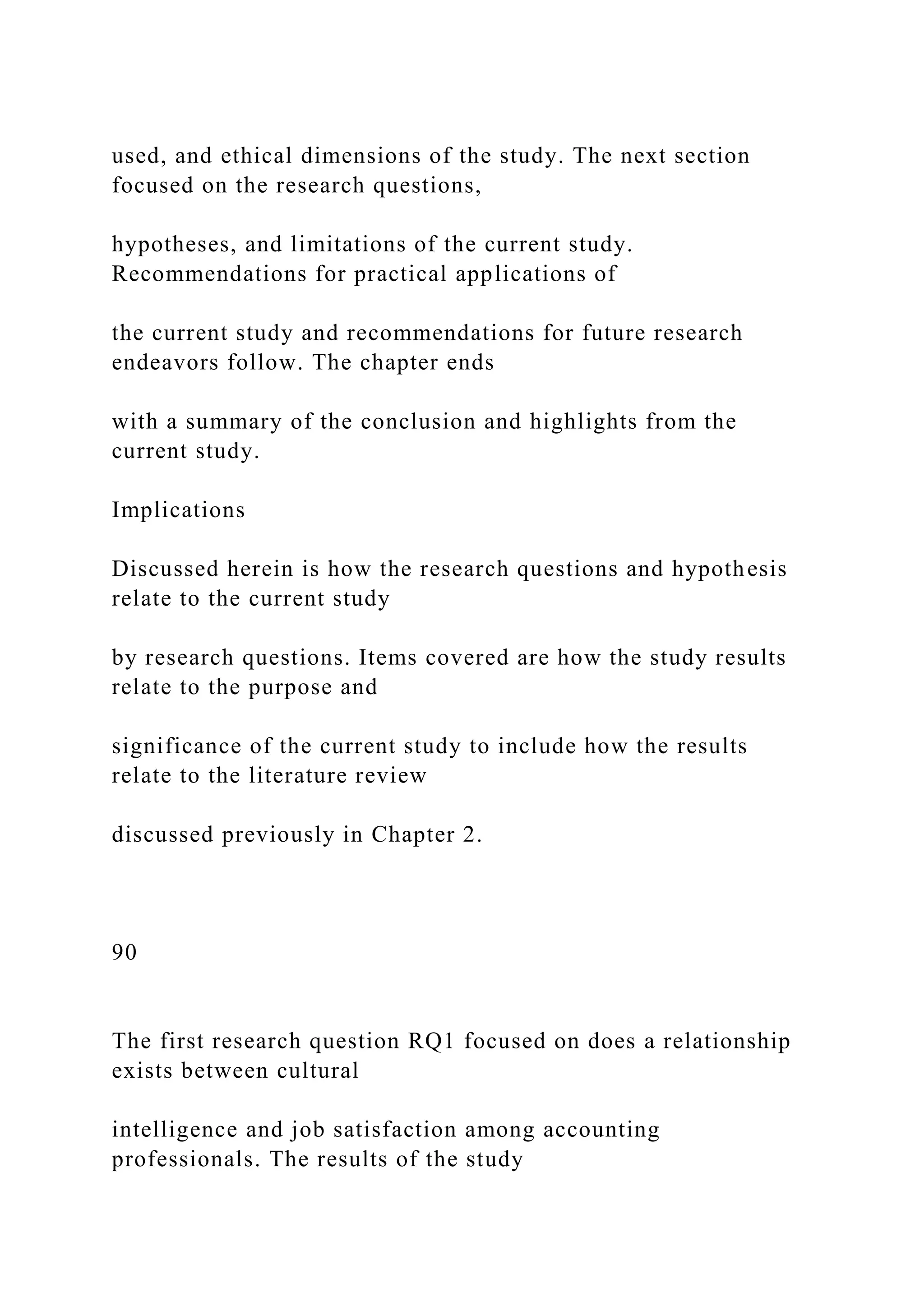

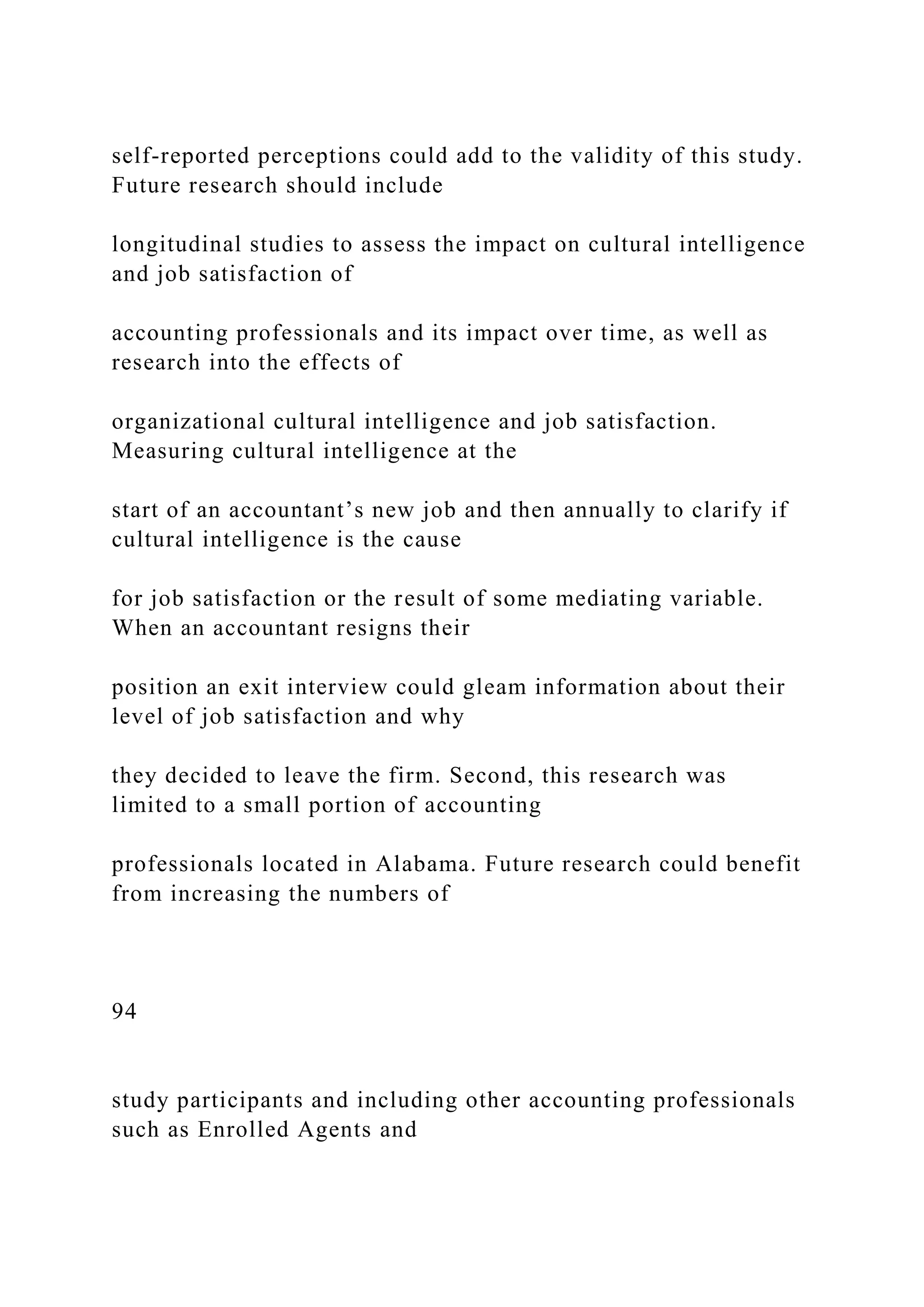

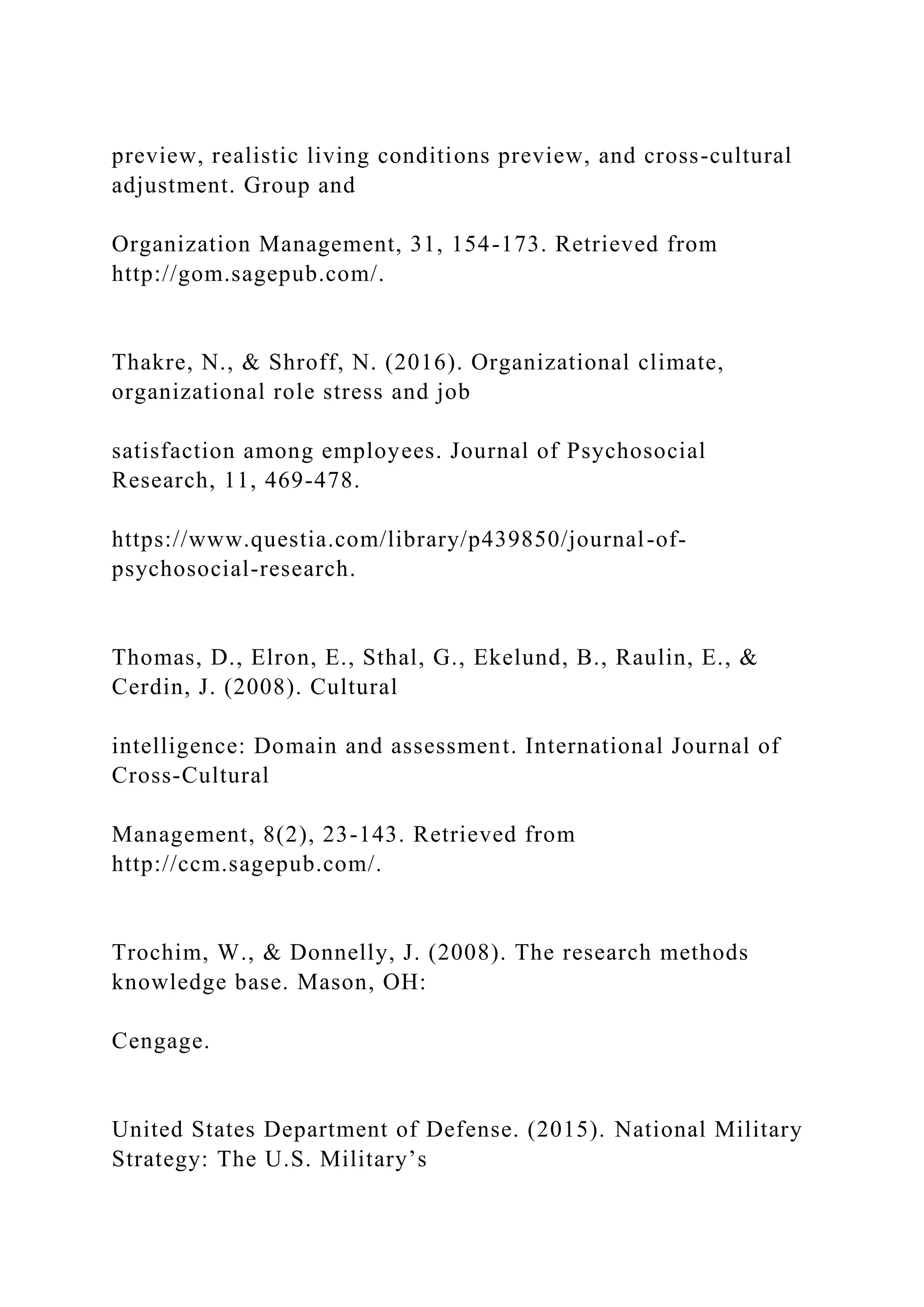

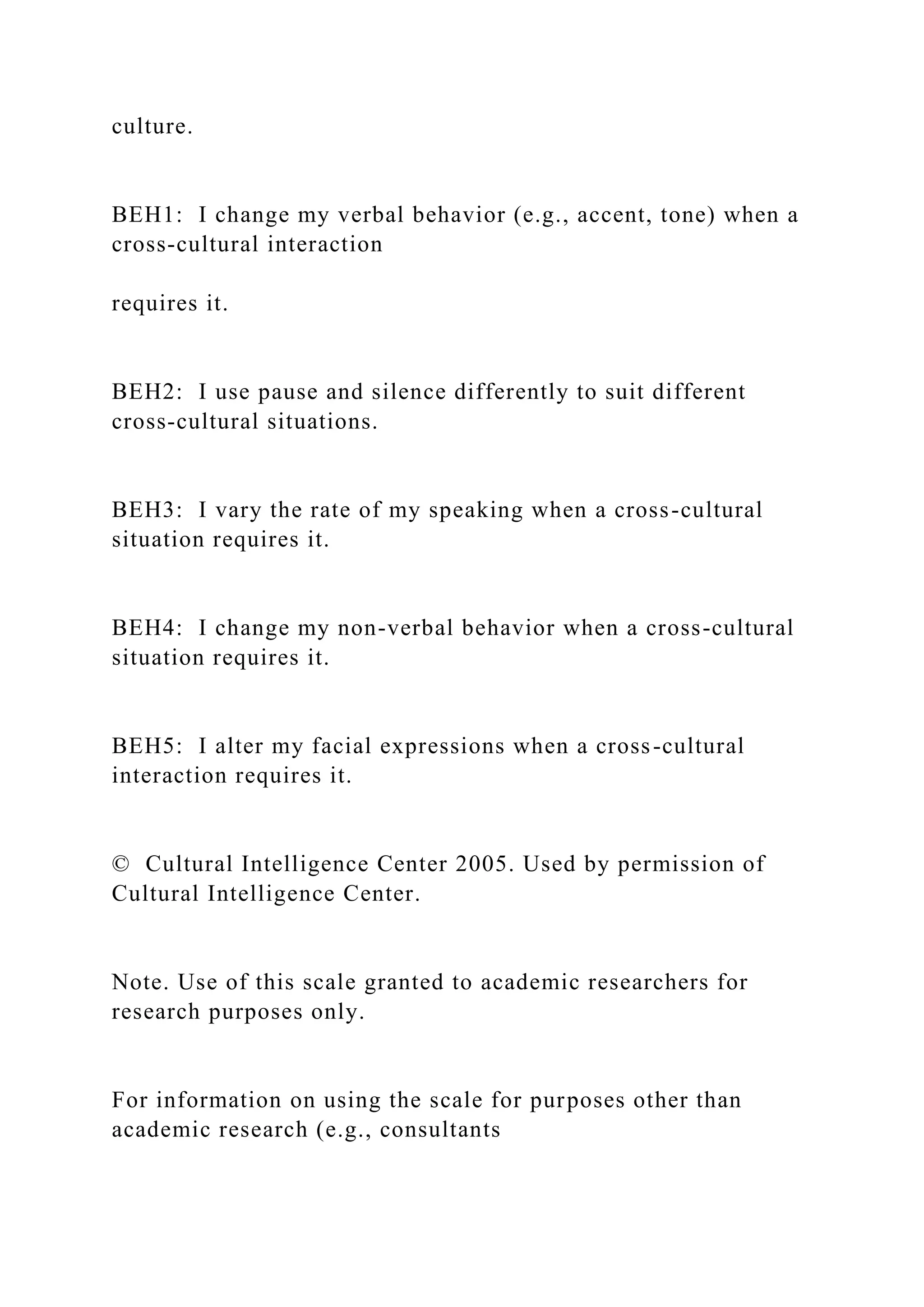

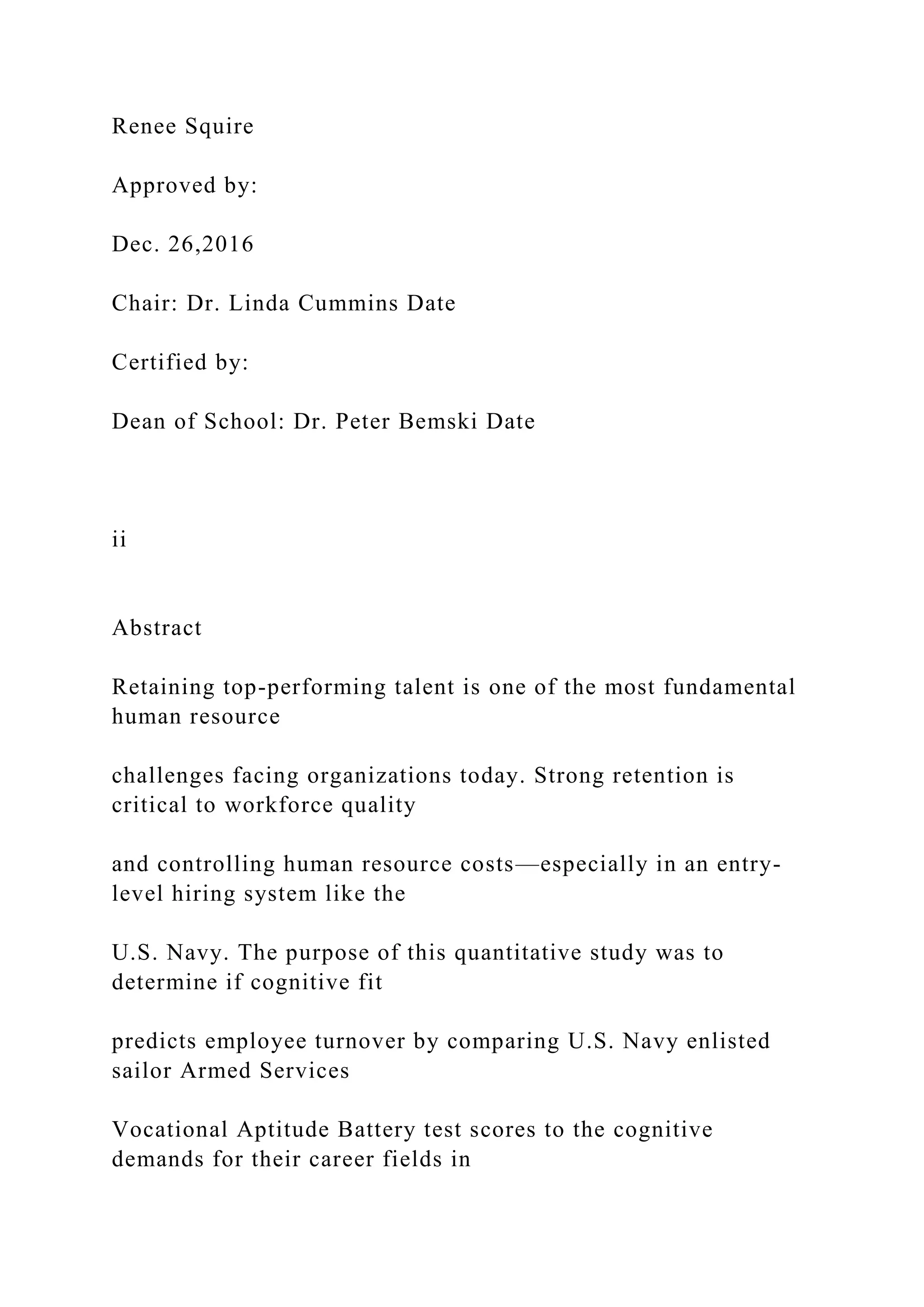

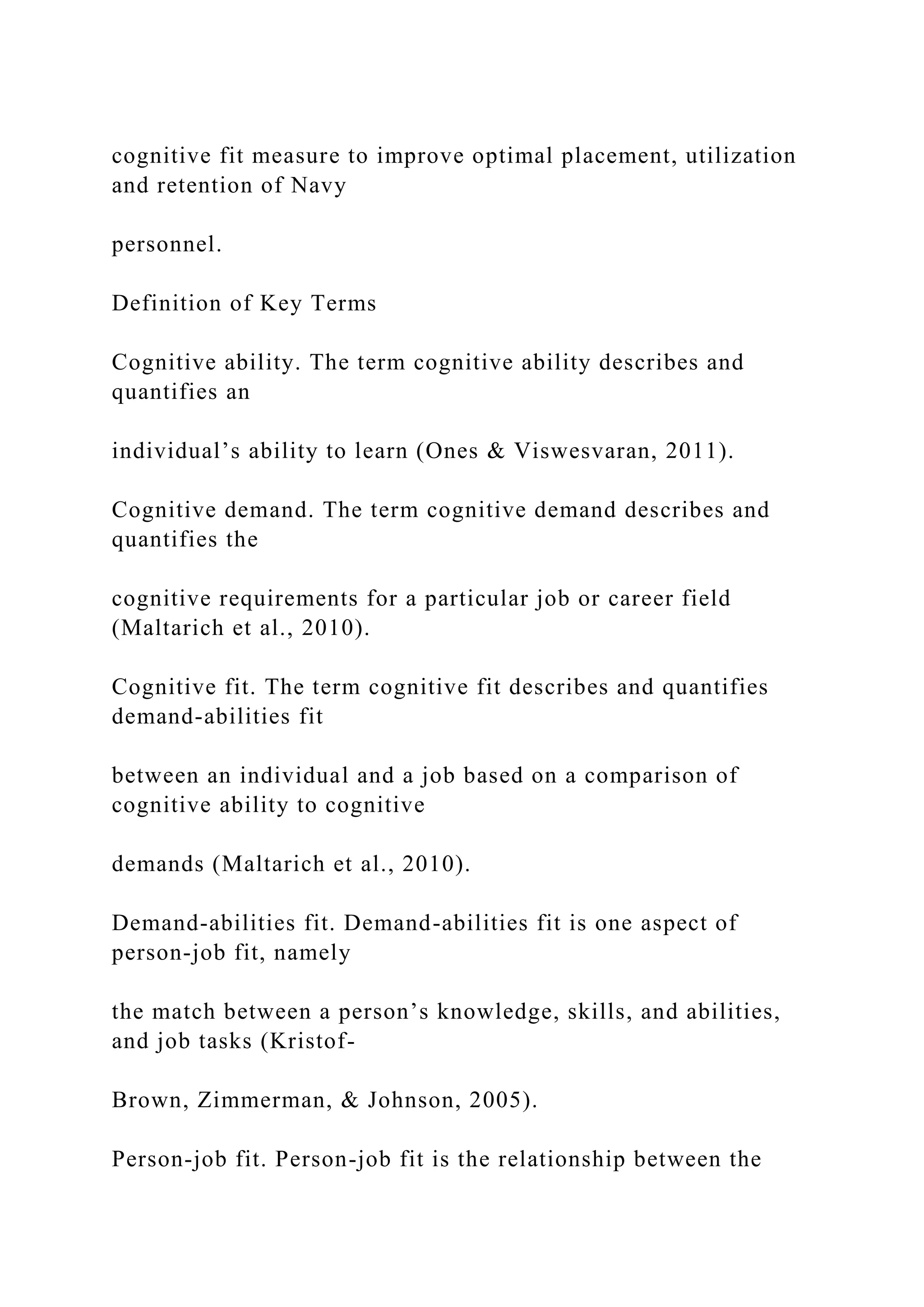

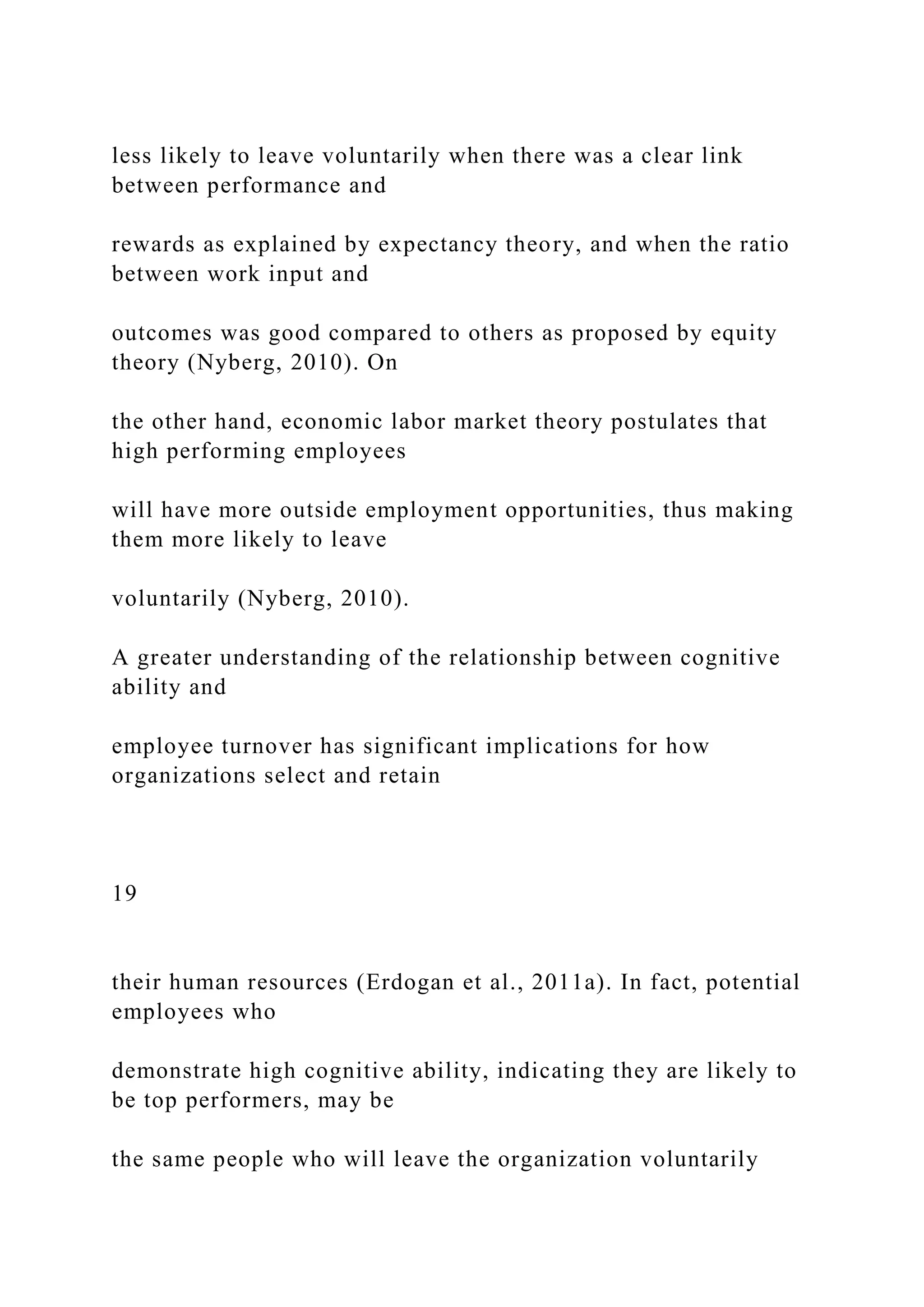

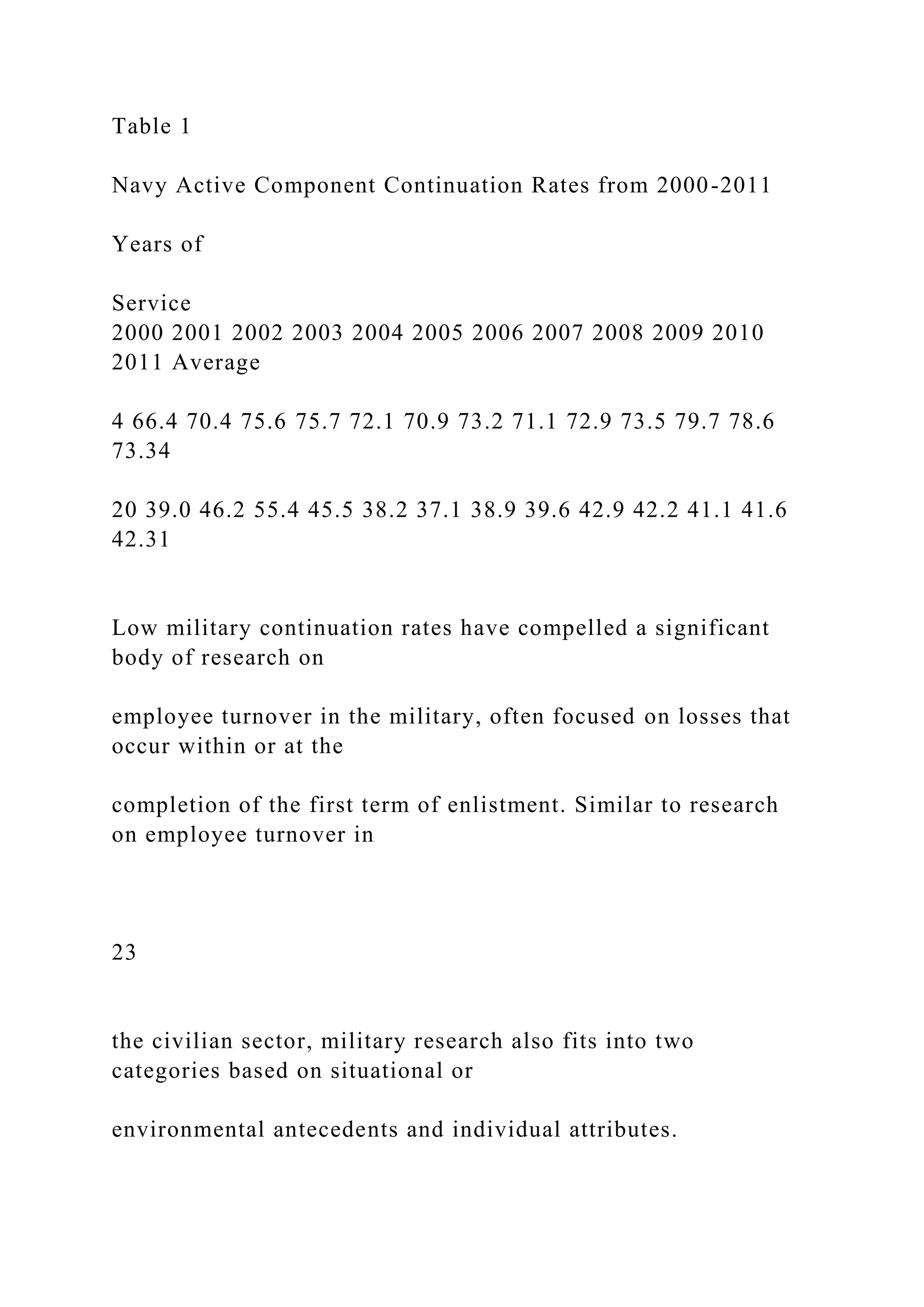

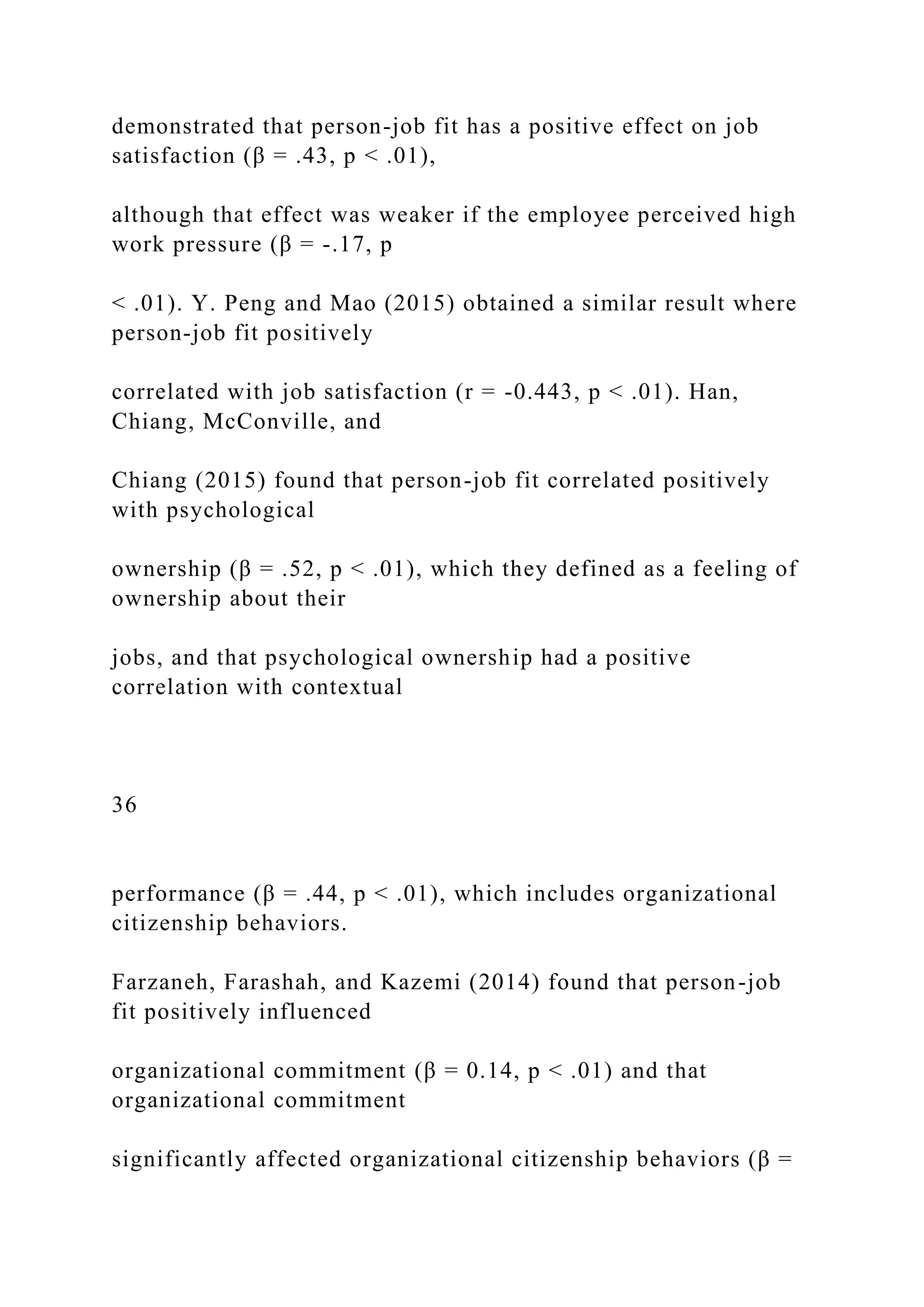

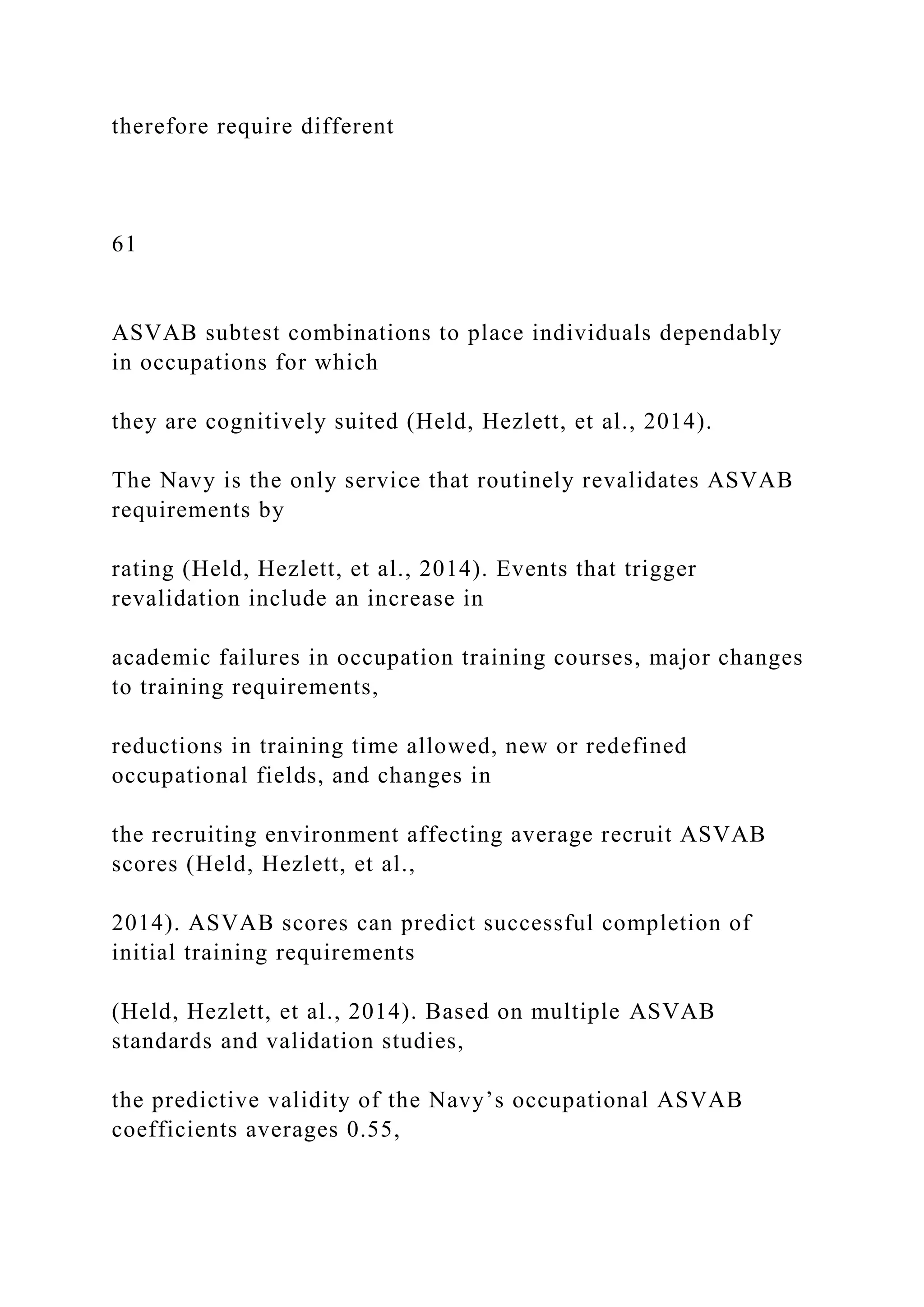

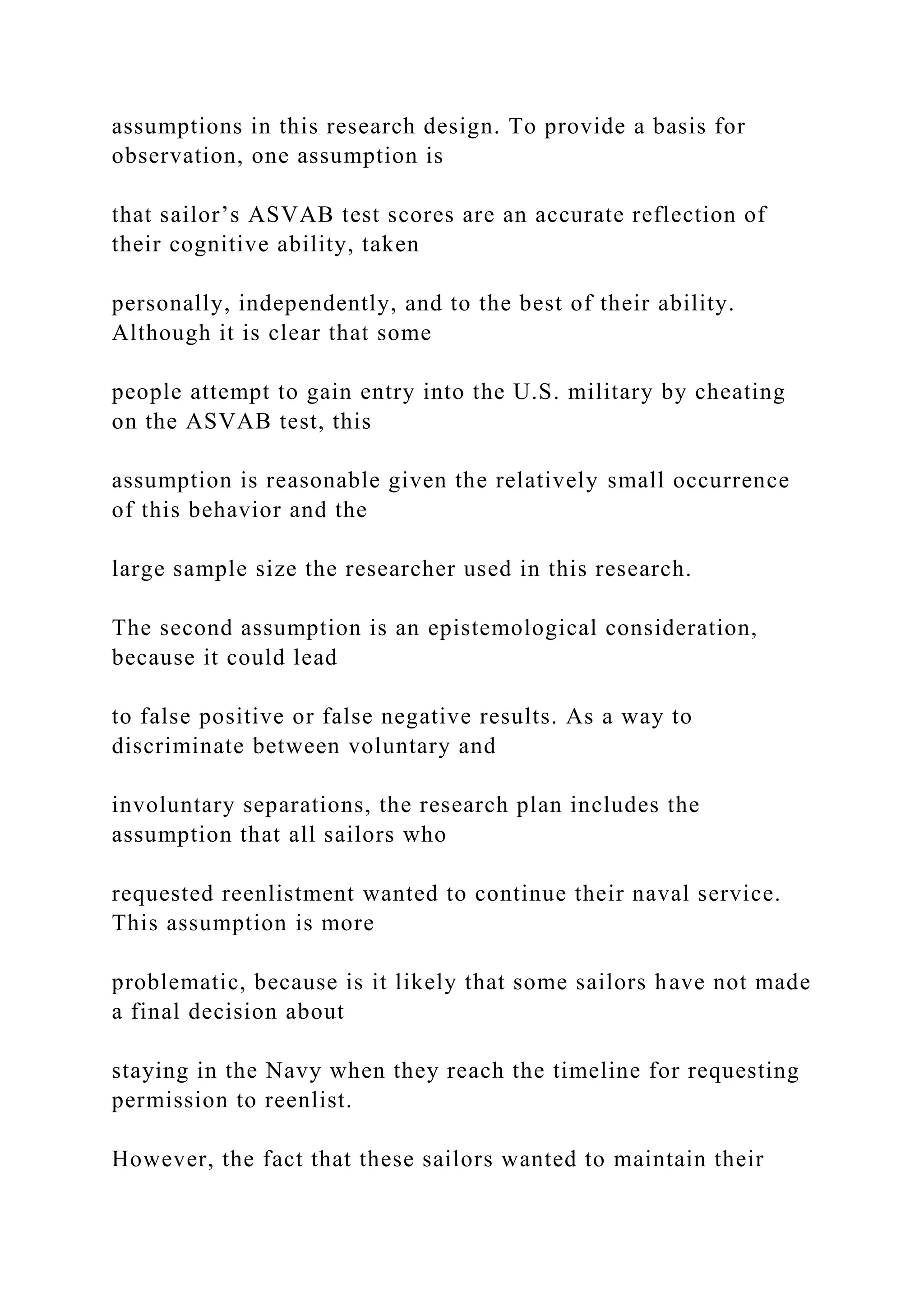

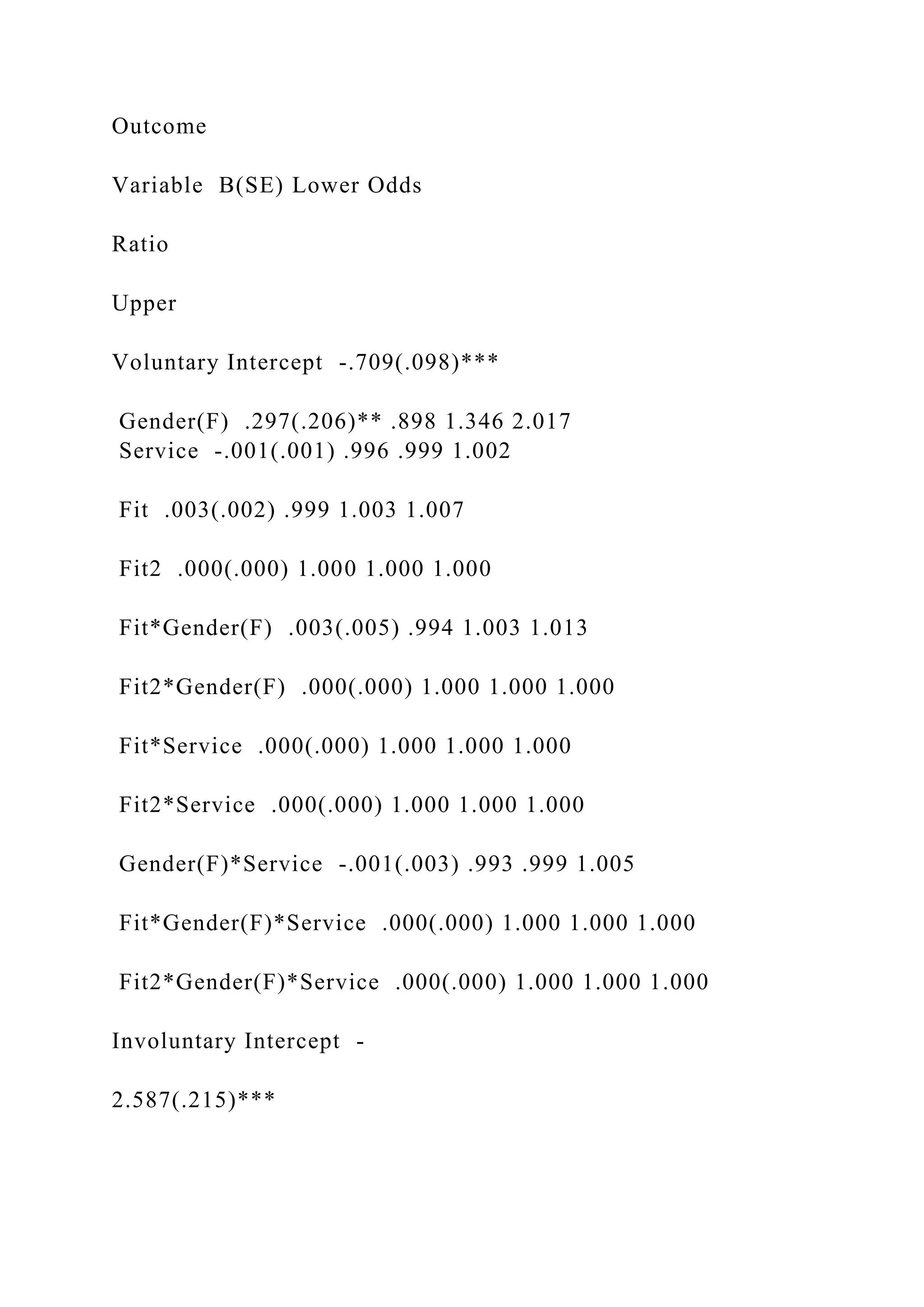

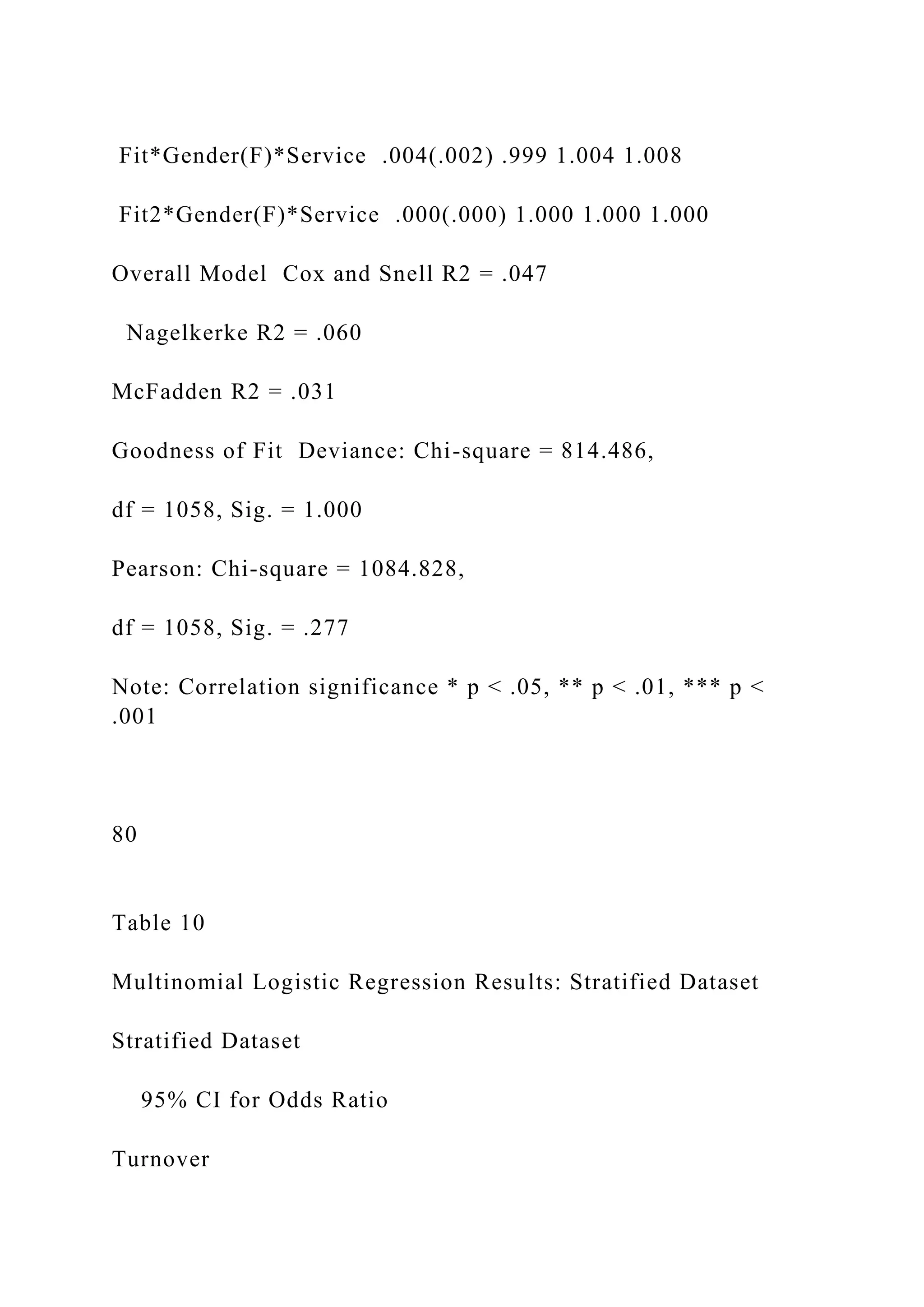

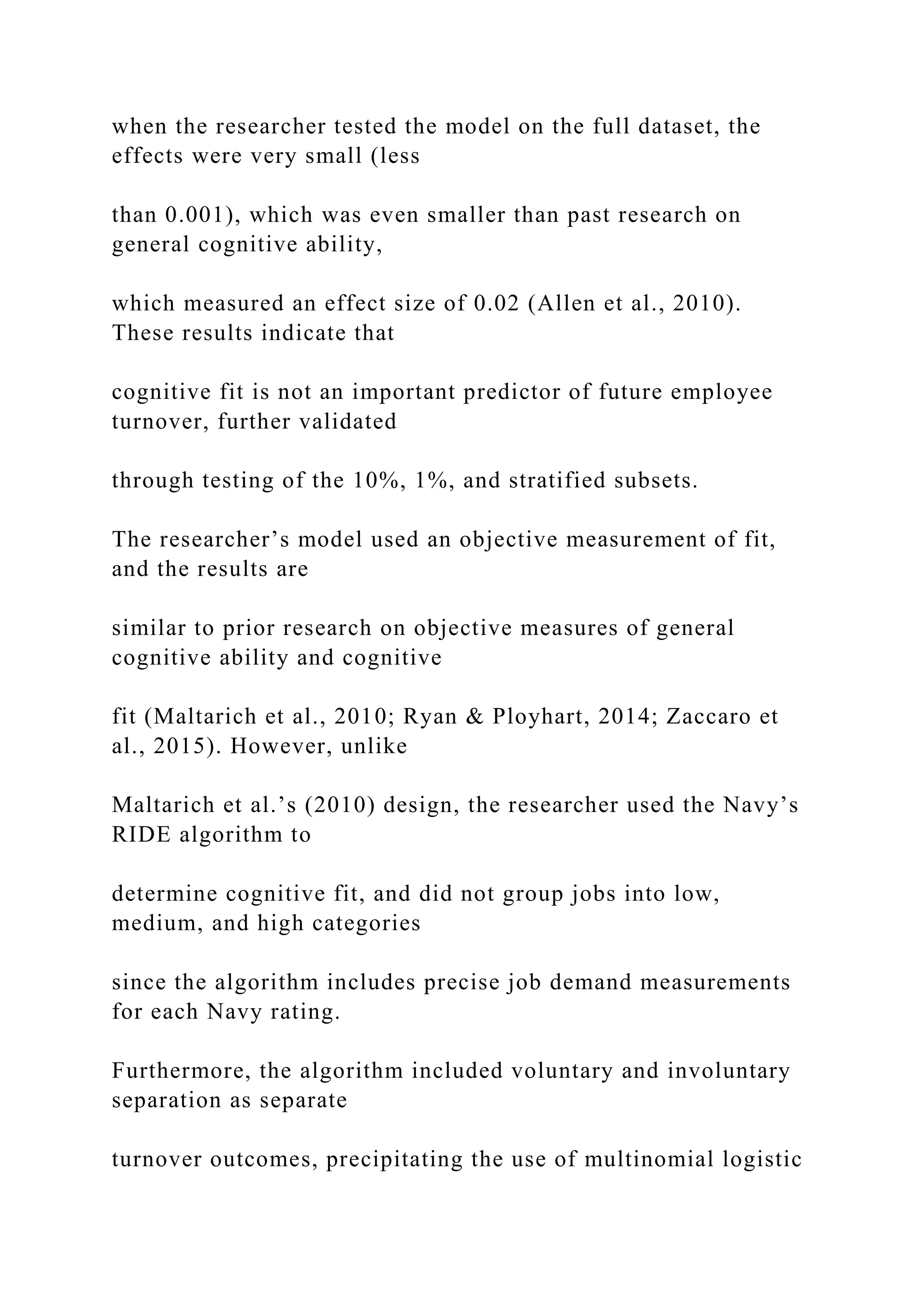

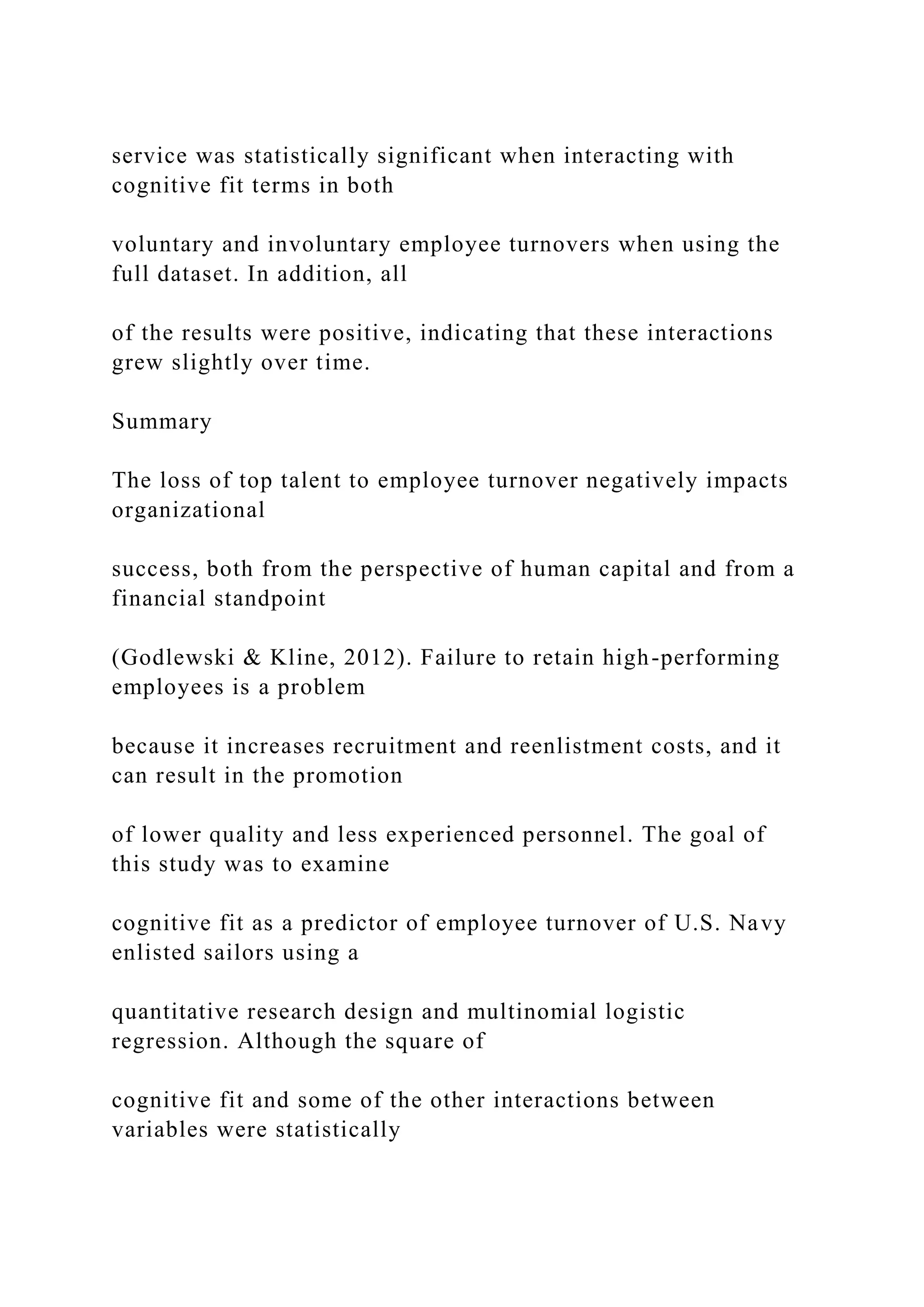

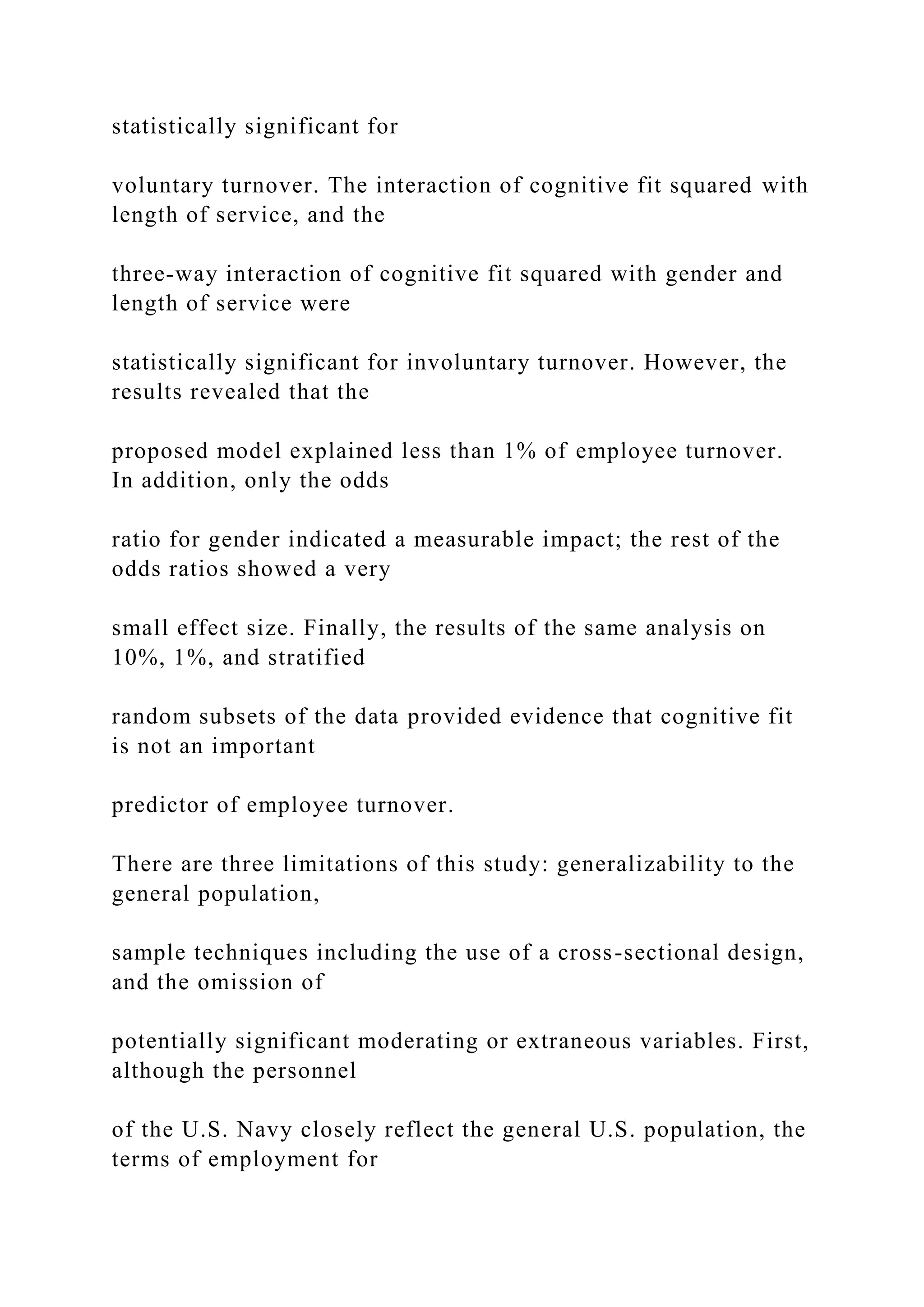

![• MIRR = {[FV(positive cash flows, reinvestment rate)/-

PV(negative cash flows, finance rate)]^(1/n)}-1.

The modified internal rate of return (MIRR) is a financial

measure

of an investment's attractiveness. It is used in capital budgeting

to

rank alternative investments of equal size. As the name implies,

MIRR is a modification of the internal rate of return (IRR) and

as

such aims to resolve some problems with the IRR.

While there are several problems with the IRR, MIRR resolves

two

of them. Firstly, IRR assumes that interim positive cash flows

are

reinvested at the same rate of return as that of the project that

generated them. This is usually an unrealistic scenario and a

more

634

likely situation is that the funds will be reinvested at a rate

closer to

the firm's cost of capital. The IRR therefore often gives an

unduly

optimistic picture of the projects under study. Generally, for

comparing projects more fairly, the weighted average cost of

capital

should be used for reinvesting the interim cash flows. Secondly,

more than one IRR can be found for projects with alternating

positive and negative cash flows, which leads to confusion and

ambiguity. MIRR finds only one value.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter11capitalbudgetingfromfinancebyboundlessisus-221019024242-5b9717e7/75/Chapter-11-Capital-Budgeting-from-Finance-by-Boundless-is-us-docx-59-2048.jpg)

![and non-academic organizations), please send an email to

[email protected]

Part III, Job in General Survey

111

112

Appendix B: Cultural Intelligence Permission Letter

113

Appendix C: JIG Permission Letter

Chapter 1: IntroductionBackgroundStatement of the

ProblemPurpose of the StudyTheoretical FrameworkResearch](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter11capitalbudgetingfromfinancebyboundlessisus-221019024242-5b9717e7/75/Chapter-11-Capital-Budgeting-from-Finance-by-Boundless-is-us-docx-351-2048.jpg)

![[email protected]

Daniel F. Wallace, PhD

Copy to:

SEA 05H - Gray

SEA 05H – Markiewicz

The SAGE Handbook for Research in

Education: Engaging Ideas and Enriching

Inquiry

The Challenge of framing a Problem: What Is Your

Burning Question?

Contributors: Susan Harter

Edited by: Clifton F. Conrad & Ronald C. Serlin

Book Title: The SAGE Handbook for Research in Education:

Engaging Ideas and Enriching Inquiry

Chapter Title: "The Challenge of framing a Problem: What Is

Your Burning Question?"

Pub. Date: 2006

Access Date: December 2, 2019](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter11capitalbudgetingfromfinancebyboundlessisus-221019024242-5b9717e7/75/Chapter-11-Capital-Budgeting-from-Finance-by-Boundless-is-us-docx-590-2048.jpg)

![Page 13 of 18

The SAGE Handbook for Research in Education: Engaging

Ideas and

Enriching Inquiry

able studies that never go beyond the elitist journals that are

shared only with like-minded scientists.) Others

have had the courage to identify issues of relevance, attempting

to stimulate public interest. One such goal

is to redress certain societal ills. Three such themes are

identified in closing this essay on the challenge of

framing a problem. Thus, it is critical that certain research-

minded investigators step out of their ivory towers

and challenge certain provocative claims, to do the needed

empirical research that will bring a sense of bal-

ance, accuracy, clarity, and realism.

In our own research, first, we have questioned the

generalization that there is rampant gender bias against

girls within the school system (American Association of

University Women [AAUW], 1992; Sadker & Sadker,

1994). Second, we have refined Gilligan's (1993) contention

that with the advent of adolescence, most girls

lose the ability to voice their opinions. Third, we have

challenged the claims of Baumeister, Smart, and Boden

(1996) that there is a “dark side to high self-esteem” in that it is

part of a constellation that predicts violence

toward others.

We believe that it is essential that dissemination of the results

of potentially relevant studies not result in over-

generalizations that can be misinterpreted, and therefore

misused, with regard to public policy. The opportu-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter11capitalbudgetingfromfinancebyboundlessisus-221019024242-5b9717e7/75/Chapter-11-Capital-Budgeting-from-Finance-by-Boundless-is-us-docx-627-2048.jpg)