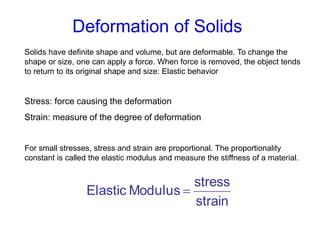

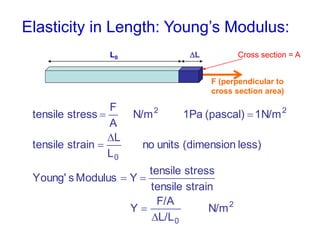

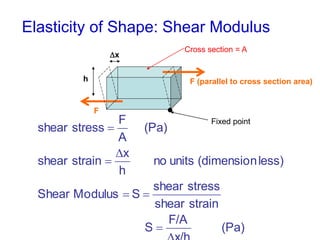

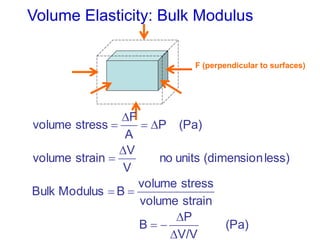

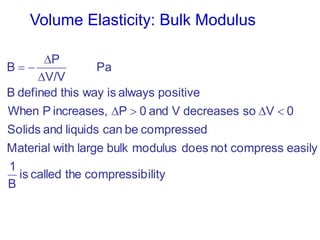

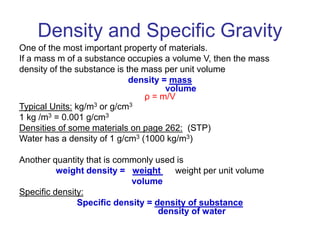

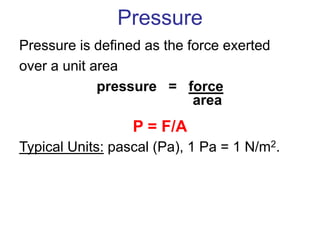

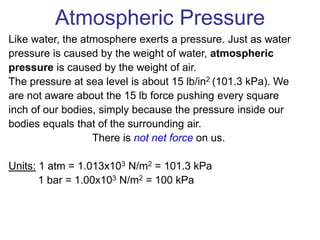

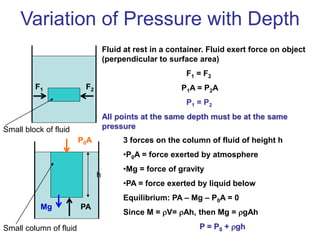

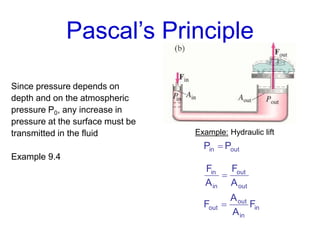

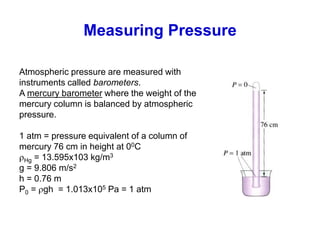

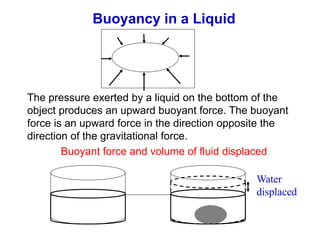

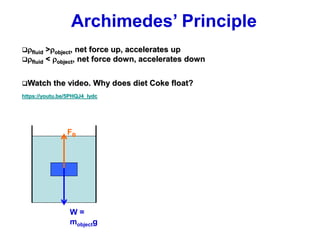

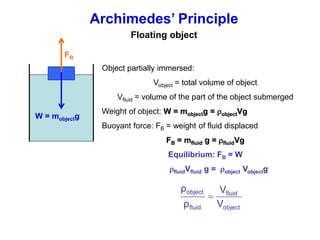

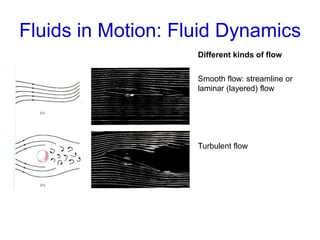

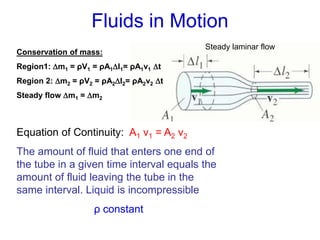

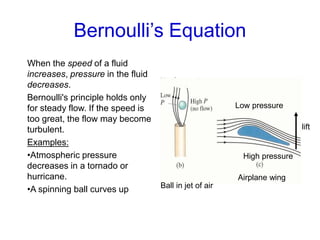

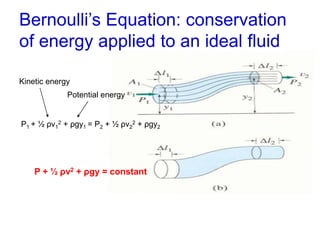

This document discusses key concepts about states of matter, properties of solids and fluids, and fluid dynamics. It defines solids, liquids, and gases, and explains how solids maintain a fixed shape and volume while liquids have a definite volume but not shape. It also covers elastic properties of solids including Young's modulus, shear modulus, and bulk modulus. Other topics include density, pressure, buoyancy, Archimedes' principle, fluid flow, Bernoulli's equation, and continuity equation.