This document discusses two damage models for predicting ductile fracture initiation: 1) the Rice and Tracey cavity growth model, which relates cavity growth rate to stress triaxiality and plastic strain increment, and predicts initiation when cavity radius reaches a critical value. 2) A damage work model, which combines plastic strain work with a term accounting for cavity growth related to hydrostatic stress, predicting initiation when damage work reaches a critical value. Finite element simulations of notched tensile specimens of two steel materials were performed to evaluate these models based on experimental crack initiation locations and steps. Both models were able to predict initiation location and step for a relatively constant critical damage value.

![156 R. Chaouadi et al.

Table 1. Chemical composition (wt-%)

C Si Mn P S Cr Mo Ni

18MND5 0.18 0.26 1.55 0.007 0.002 0.18 0.50 0.65

22NiMoCr37 0.30 0.23 0.71 0.009 0.011 0.47 0.80 0.71

Table 2. Mechanicalproperties

0.2% yield stress Tensilestrength Elongation Reduction of area

#u(MPa) ~r~(MPa) ~% A%

18MND5(20°C) 525 670 22.5 70

22NiMoCr37(100°C) 517 670 19.8 61

Furthermore, all the tests have been performed under controlled displacement at a constant

crosshead speed. The load and the crosshead displacement are continuously recorded, as well

as the diameter contraction by an LVDT.

The specimens are identified by the notation NTSp for Notched Tensile Specimen followed

by the notch radius p. Typical mean strain-mean stress curves obtained from different notched

specimens are shown in Fig. 1. As can be seen, the sharpness of the notch drastically reduces

the ductility of the specimen because of the important role played by the hydrostatic component

of the stress tensor.

4. Finite element simulation

The stress-strain calculations are performed using the SYSTUS finite element code. Because

of the axial symmetry, only a quarter of the specimen is simulated using two dimension

isoparametric 8-node elements with reduced Gauss integration. The von Mises criterion for

plasticity is used with associated incremental flow rule.

The load application is simulated by a vertical displacement of the nodes situated at the

upper face. Because of the large strains and deformations, the updated Lagrangian procedure

is used. The BFGS algorithm is used to solve the constitutive equations.

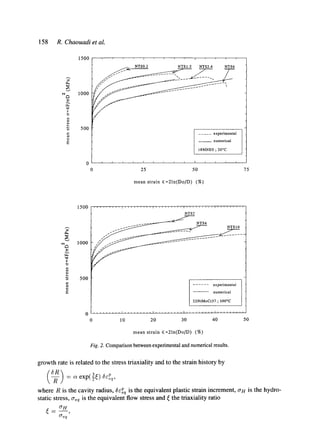

The comparison of experimental results with numerical calculations shows an overall good

agreement (Fig. 2).

The stress triaxiality ratio (O'H/O'eq),where O"n and Cr~qare respectively the hydrostatic

and equivalent stresses, at the centre of specimen calculated from the Bridgman [1] formula

is underestimated with regard to finite element calculations. However, the correlation is very

good in the early stage of loading, except the NTS 0.2 geometry (Table 3).

The triaxiality ratio is maximum at the centre of the specimen for all geometries, except

for NTS 0.2 where it is maximum in a region close to the notch (t0.5 mm from the notch).

Similarly, the crack initiates at the centre of each specimen except the NTS 0.2-specimen

where it cracks from the notch.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chaouadi1994-190825163016/85/Chaouadi1994-2-320.jpg)

![Damage work as ductile fracture criterion 157

II

r,

E

1500

1000

500

0

0 100

NTS0.2 NTS1.2 NTS2.4 NTS6 NTS12 NTS60

J ~ material: 18MND5

room temperature

NTSR Do=6mm

i i i I T i i i I r i i r t i r i I

25 50 75

mean strain E=21n(Do/D) (%)

Fig. 1. Strain-stress curves - influence of stress triaxiality.

Table 3. Stress triaxiality at the centre of specimen

NTS0.2 NTS1.2 NTS2.4 NTS6 NTS2 NTS4 NTS10

Bridgman 2.47 1.14 0.82 0.56 1.14 0.82 0.56

EE.M. (early stage) 1.35 1.07 0.81 0.54 1.08 0.80 0.54

EE.M. (mean) 1.28 1.39 1.12 0.86 1.37 1.07 0.80

5. Damage modelling

Physically, ductile damage is related to the nucleation, growth and coalescence of cavities. The

nucleation and coalescence phases are negligible compared to the growth phase, and therefore

are not taken into account in this model. Many authors [2-10] have shown the important role

played by the hydrostatic stress. Therefore, it is expected that this component will appear in the

damage function. In addition, because of the damage process which is a cumulative process,

the plastic strain increment will be the loading factor which represents the strain history.

5.1. CAVITY GROWTH MODEL

Rice and Tracey [11] have calculated the displacement field of a perfectly plastic material

containing a spherical cavity and subjected to remote stress and strain-rate fields. They derived

a relation between the cavity radius rate and the stress-strain field. The damage is then related

to the cavity radius, and crack initiation occurs for a critical radius of the cavity. This cavity](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chaouadi1994-190825163016/85/Chaouadi1994-3-320.jpg)

![Damage work as ductilefracture criterion 159

a is a constant factor, and according to Rice and Tracey [11] for high triaxialities, a = 0.283.

However, this value has been corrected by Huang [12] who found a better approximation for

a = 0.427. Furthermore, Marini [13] has shown that a is actually proportional to the volume

fraction of second phase particles. Nevertheless, in this model, its value is not critical because

it appears as a proportional parameter that can be fitted experimentally.

Crack initiation occurs when R reaches its critical value Rc, which is an intrinsic property

of the material. This model has been successfully used by many authors [5, 6, 9, 10, 14].

5.2. DAMAGEWORKMODEL

Another way of characterizing the ductile damage is obtained from the expression giving the

plastic work per unit volume. Plastic strain work is given by

8WD = aij&r~j.

Using the deviatoric stress expressions, this equation can be written as

In plasticity problems, ~i = 0 to satisfy the incompressibility condition, and therefore, the

hydrostatic stress O'H does not contribute to plastic deformation. This is experimentally well

verified. However, locally, in particular for high plastic strains, this is no longer valid. Ductile

fracture is a cavitation process, and locally, the volume change should be taken into account

when evaluating the plastic strain work.

The volume change (~V/V) can be related to the cavity growth rate of Rice and Tracey by

~V 8R

V R

Therefore

(SR

~WD = Creq~CPeqq- 3(rH

R

Rearranging this equation leads to

~W~ = [1 + 3~¢ exp(3¢)] ~q~q.

As can be seen from this equation, there is a competition between plastic flow and cavity

growth. ~WD will be called 'damage work'. Fracture occurs when damage work reaches

a critical value noted WDC, characteristic of the material. The first term is related to the

dislocation creation process by plastic deformation whereas the second term is related to the

cavity creation process.

As before, the factor o~is an experimental fitting parameter. However, this factor could

be correlated to the microstructure of the material, in the sense that it will represent also the

distribution of the second phase particles in the material. So, any scattering in the data will be

reflected by a.

The damage model given here is very similar to the one proposed by Zhang et al. [15,

16]. However, the derivation is different although the conceptual idea of competition between

material flowing and cavitation is the same. Indeed, they combined the void multistage

nucleation model to the Gurson [17] potential for porous materials to derive what they called

the 'combinatory work density'.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chaouadi1994-190825163016/85/Chaouadi1994-5-320.jpg)

![160 R. Chaouadi et al.

Table4. Critical damage of the different specimens

eP~q(%) (R/Ro)c Wac(Jlmm3)

18MND5 --

NTS 1.2 21 1.63 1.61 (2.35)(*)

NTS2.4 37 1.74 1.67 (2.38)

NTS6 58 1.76 1.57 (2.13)

NTS0.2 64 1.80 1.61 (2.17)

22NiMoCr37

NTS2 18 1.47 1.28 (1.87)

NTS4 28 1.48 1.18 (1.67)

NTS10 50 1.59 1.30 (1.76)

* Values corresponding to ¢r --- 0.428.

6. Results and discussion

These two damage models, i.e. Rice and Tracey cavity growth and damage work have been

calculated in the meshes of the minimum cross section of the different notched tensile spec-

imens (Fig. 3). Their evolution in the minimum section clearly shows the expected critical

region of crack initiation. Thus, the crack initates at the centre of all specimens but at the notch

for NTS 0.2-specimen, as predicted by both models. Furthermore, at crack initiation, their

critical value is relatively constant, independent from the notch sharpness. In both models, the

finite element calculations have been performed assuming avon Mises material. This means

that the damage and the constitutive relations are non-coupled, whereas in the case of the

Gurson model [17], they are coupled.

The tensile properties of both steels being very similar (see Table 2), one would expect

quite similar critical damage values. The reason could be assigned to the factor, a, proportional

to the second phase particles. So, the main inclusions present in such steels being MnS-type,

according to Franklin [18], their density can be evaluated from the chemical composition

using the relation

0.001]

fMnS(%) = 5.4 %S %MnJ '

where, %S and %Mn are the weight-% of sulphur and manganese, respectively, and fMnSis the

volume fraction of MnS-inclusions. This relation agrees well with experimental measurements

for ferritic steels [6]. Given both compositions of the steels under consideration, this relation

gives fMnS = 0.007% for 18MND5 and fMnS = 0.05% for 22NiMoCr37. Therefore, the

factor ~ for 22NiMoCr37 should be higher than for 18MND5. Another possible reason for

the difference of critical damage values between these steels is the specimen size effect, as

suggested by Marini [13]. The critical cavity growth ratio and the critical damage work for

each material and geometry have been deduced and are given in Table 4. These values have

been obtained by integrating the damage functions from zero to the mean strain corresponding

to crack initiation derived from the experimental tests.

This table shows that (R/Ro)c increases with local plastic strain. Beremin [2, 3] showed

that this model should take into account the decohesion strain necessary to initiate a cavity.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chaouadi1994-190825163016/85/Chaouadi1994-6-320.jpg)