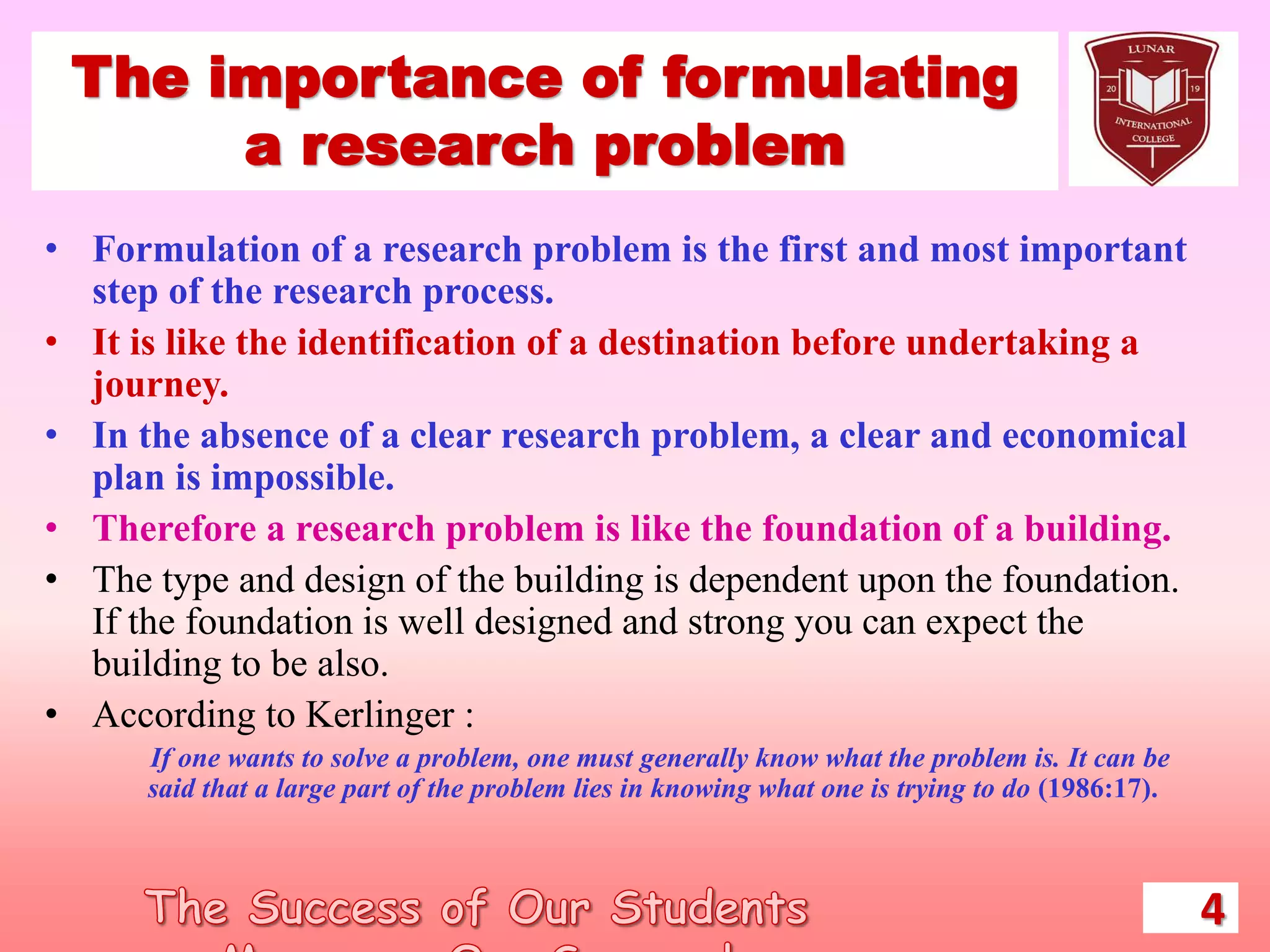

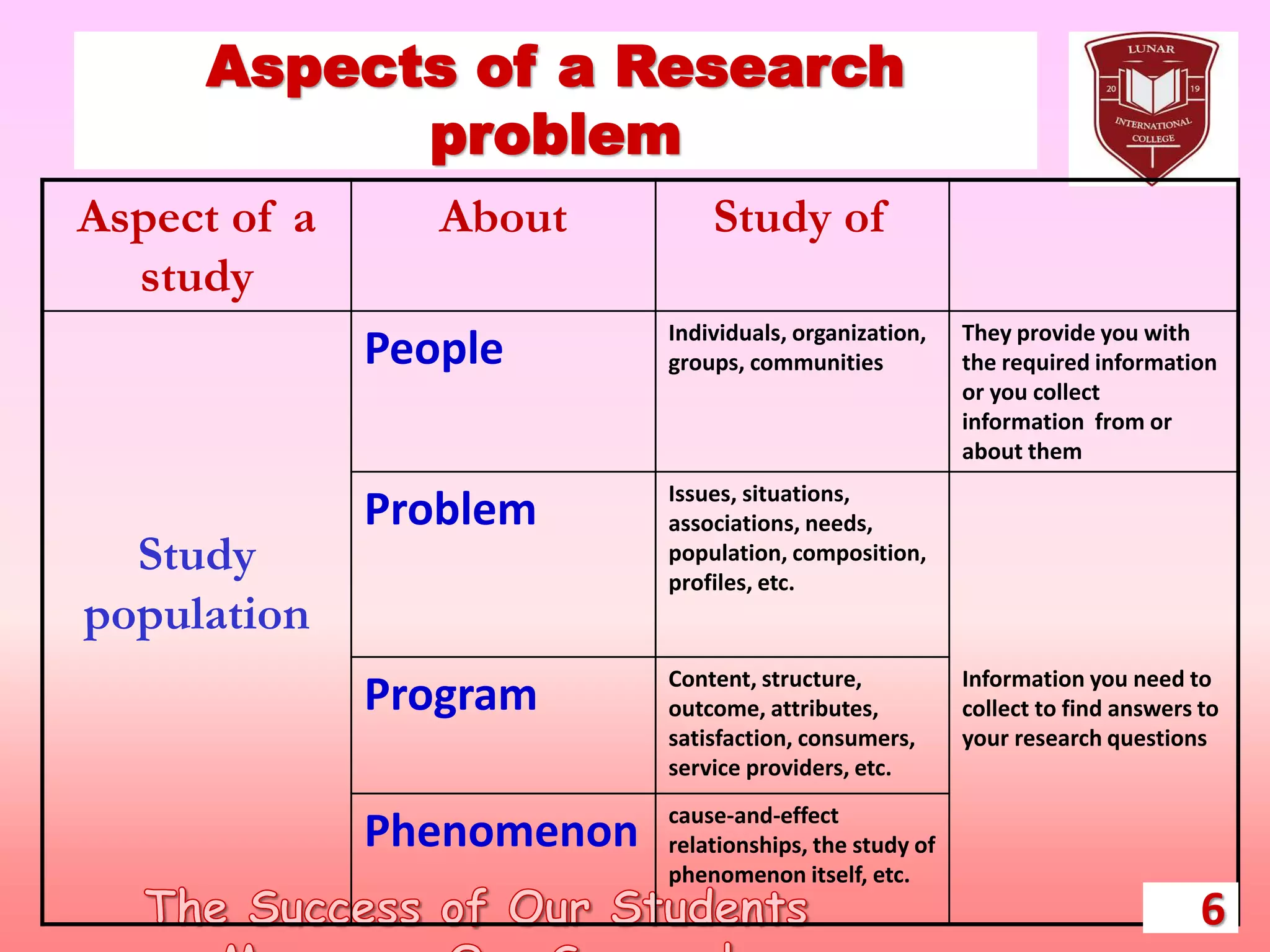

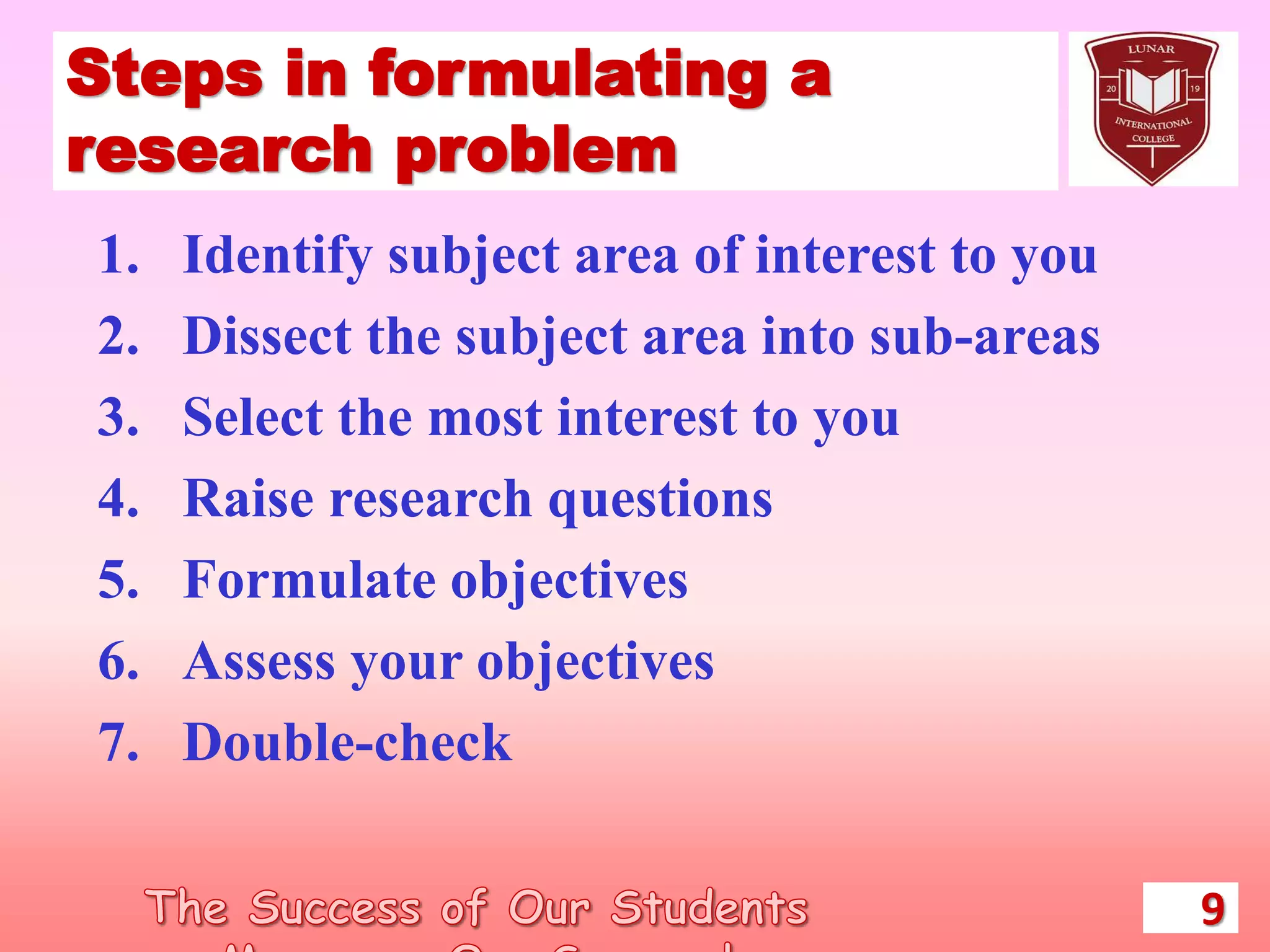

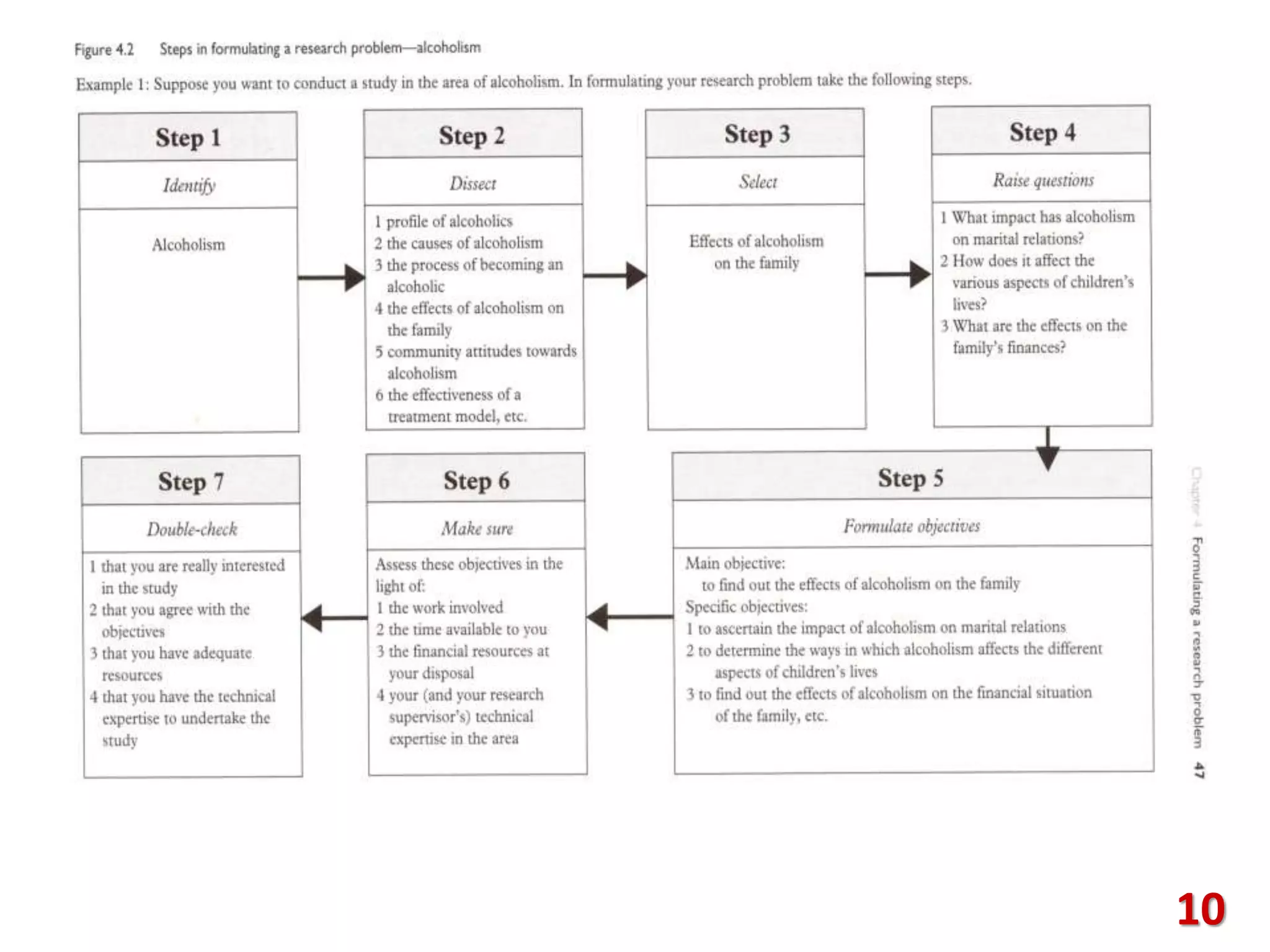

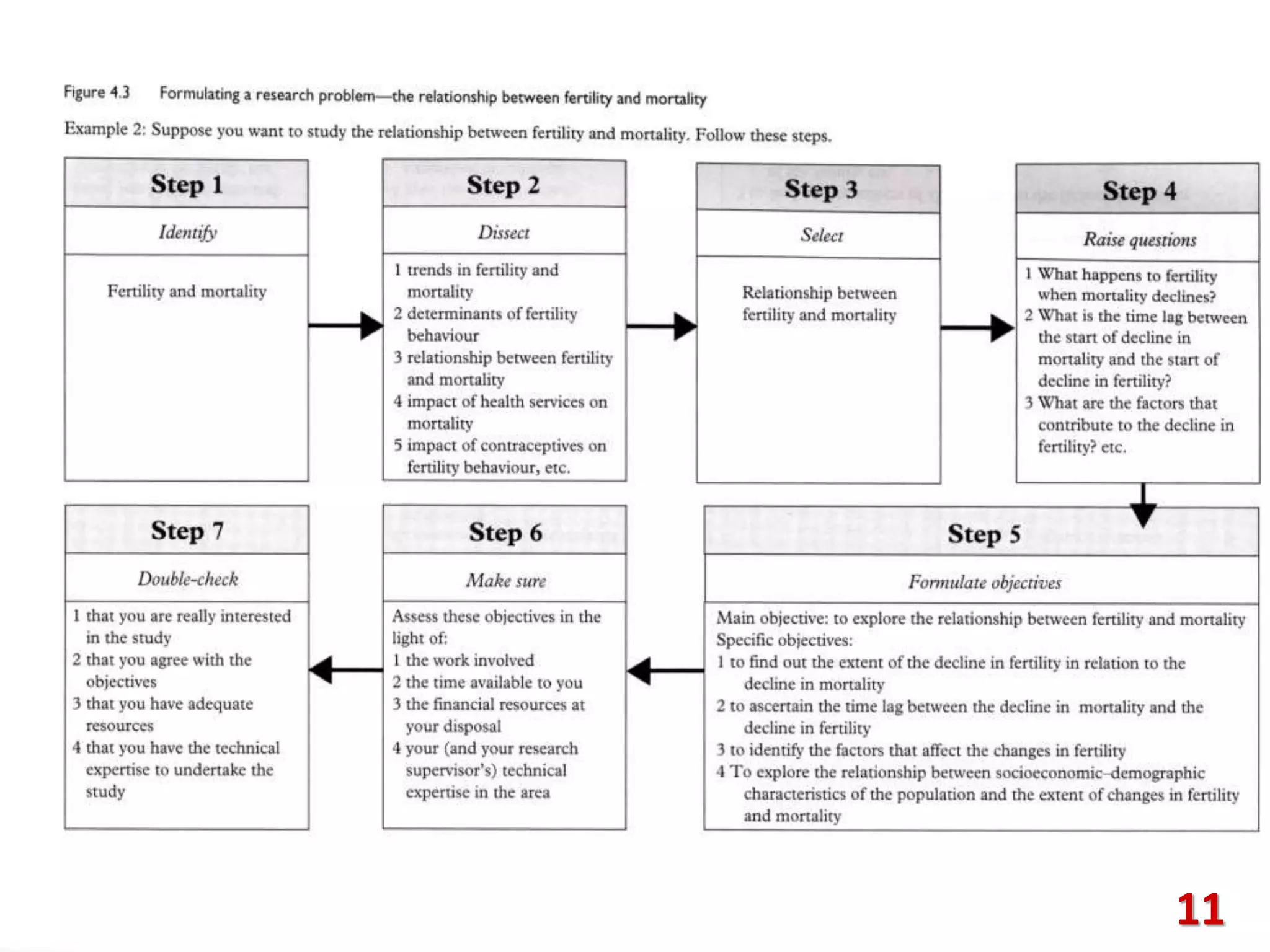

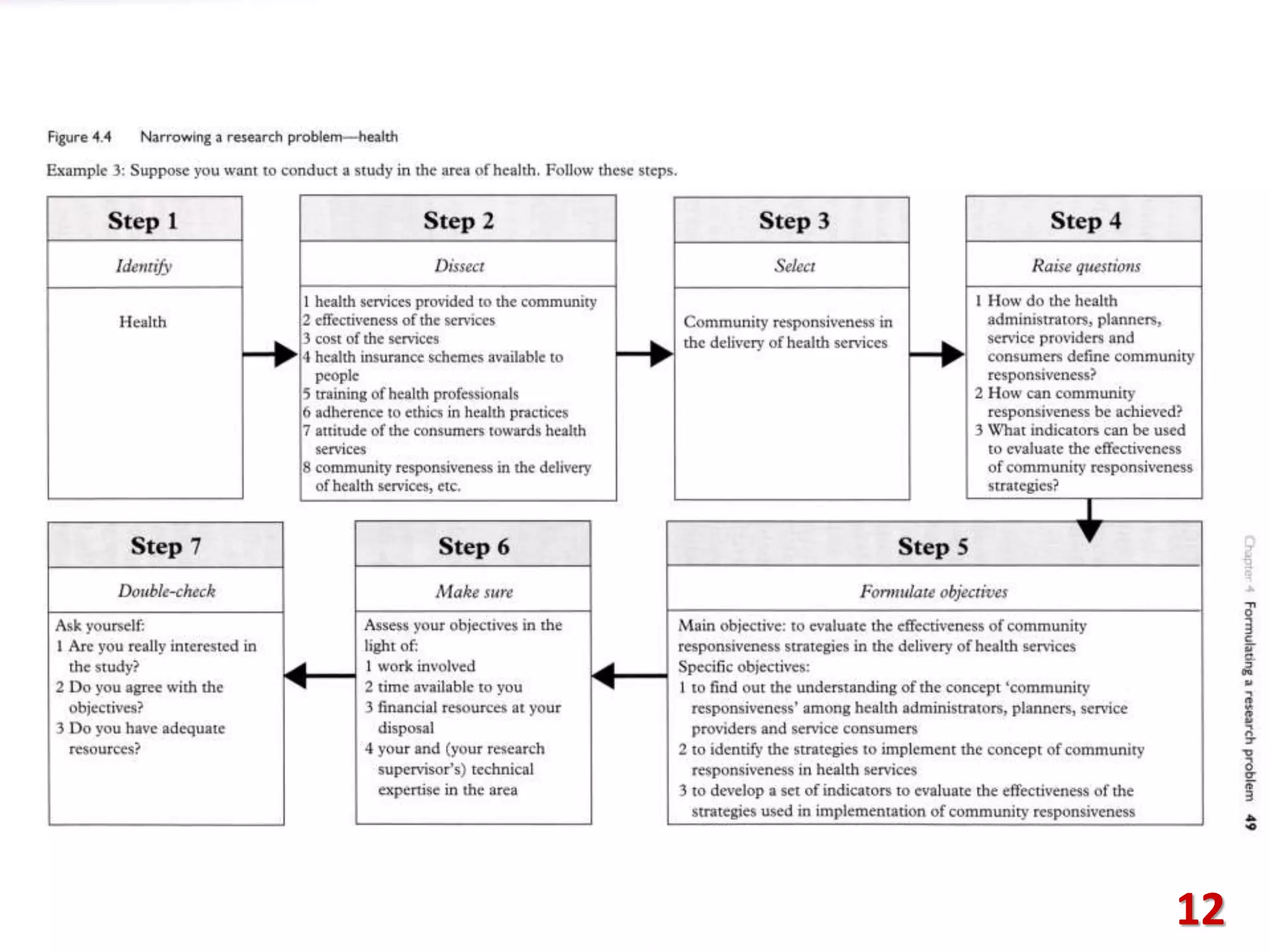

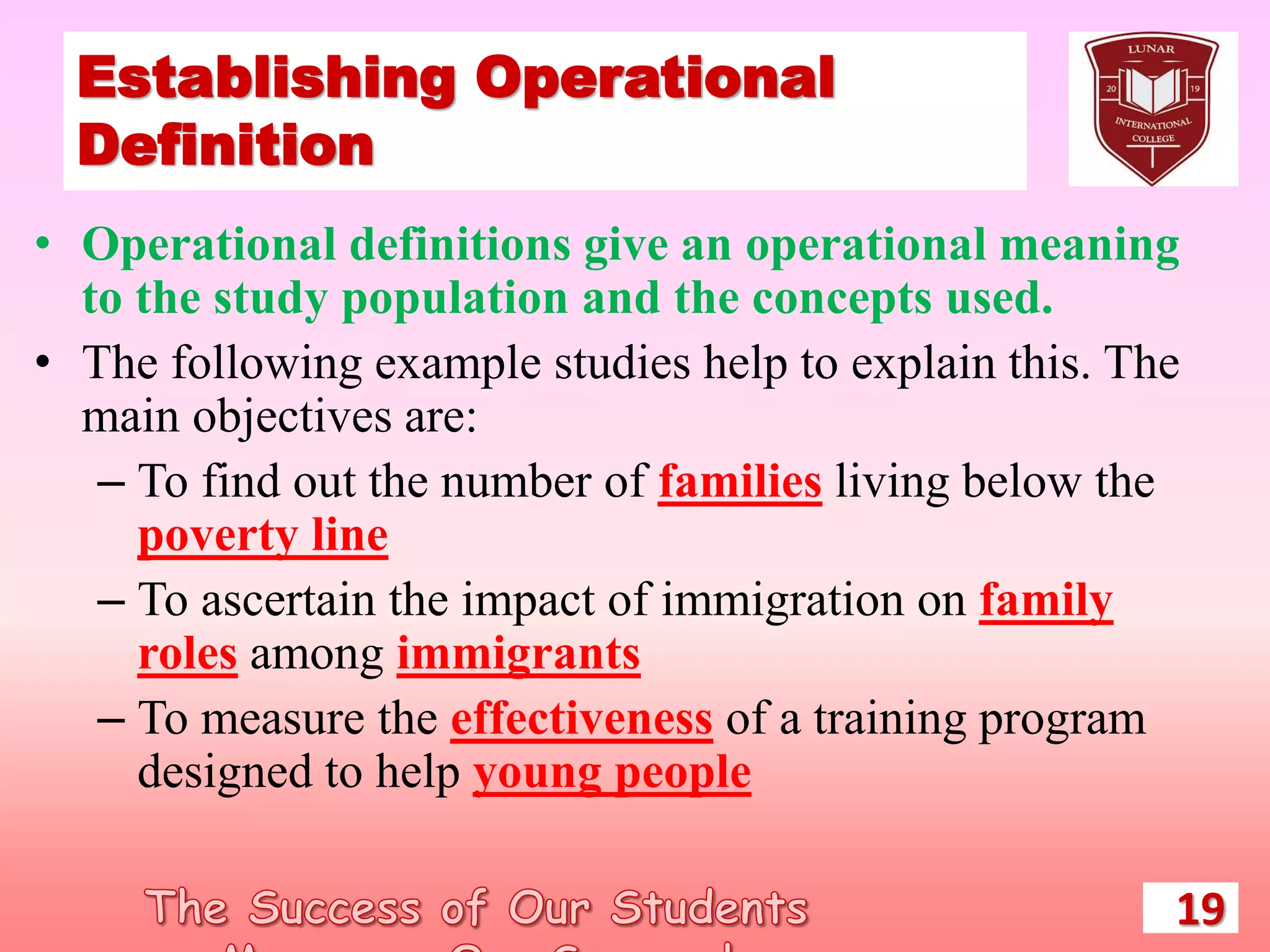

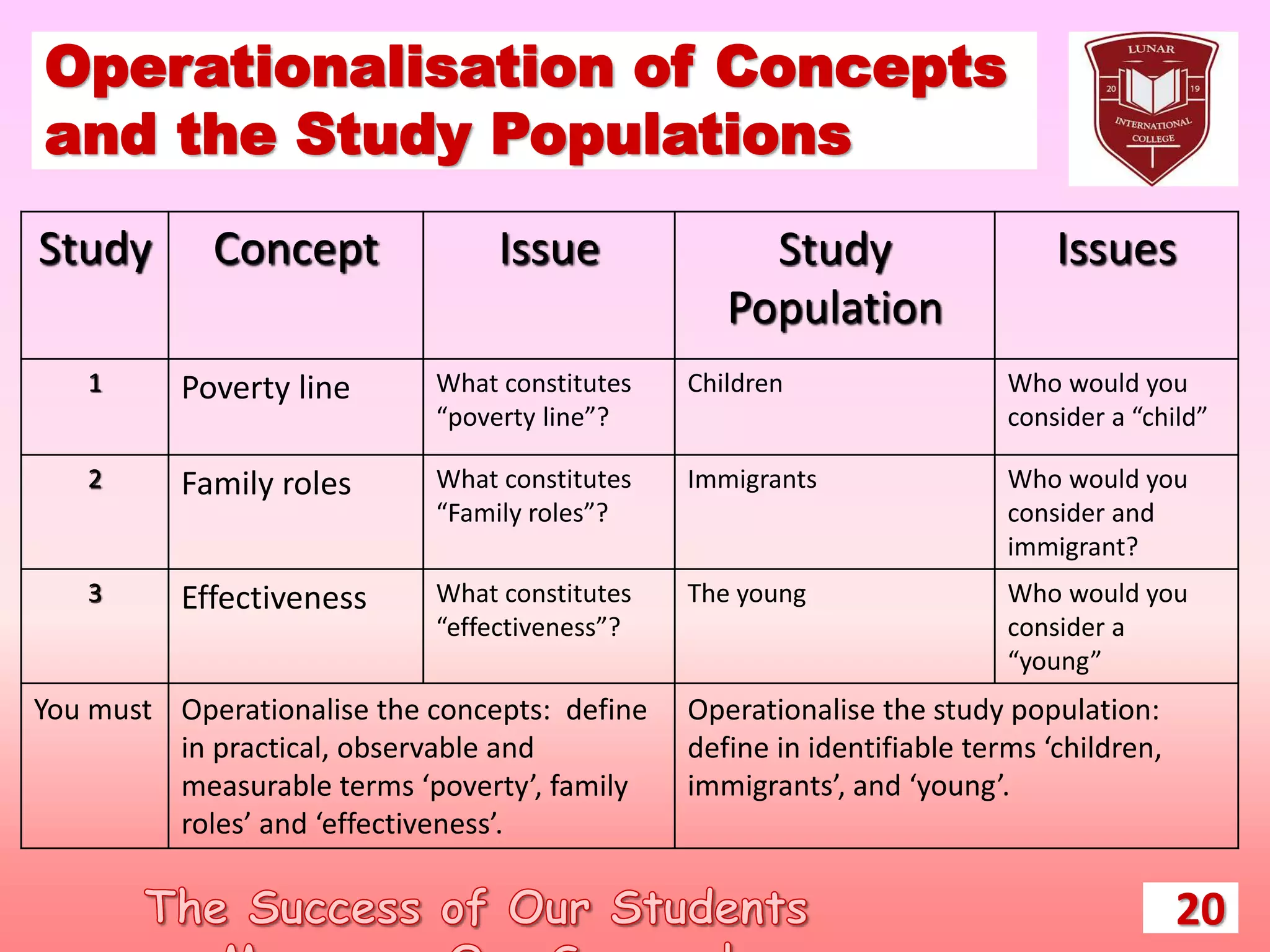

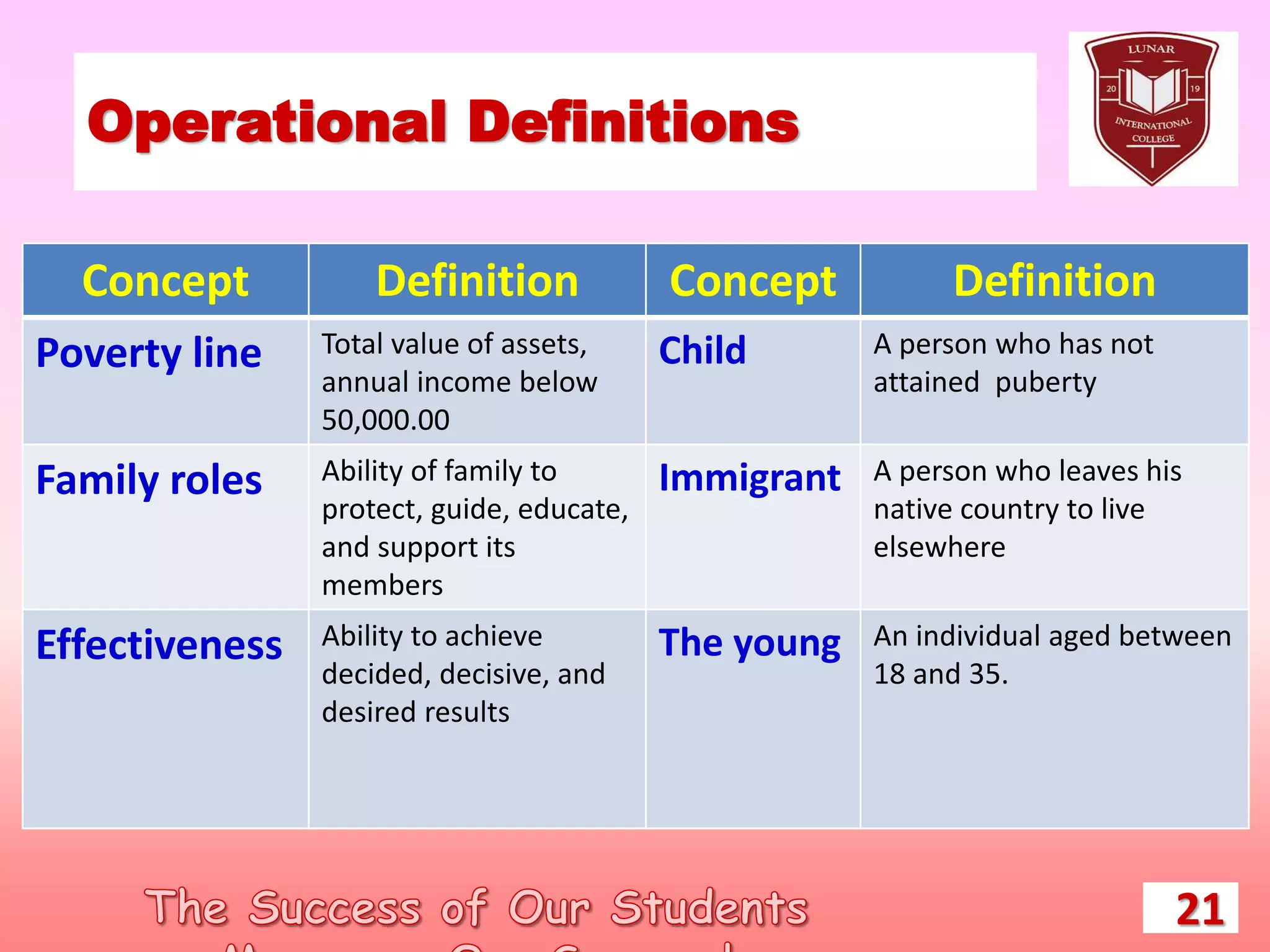

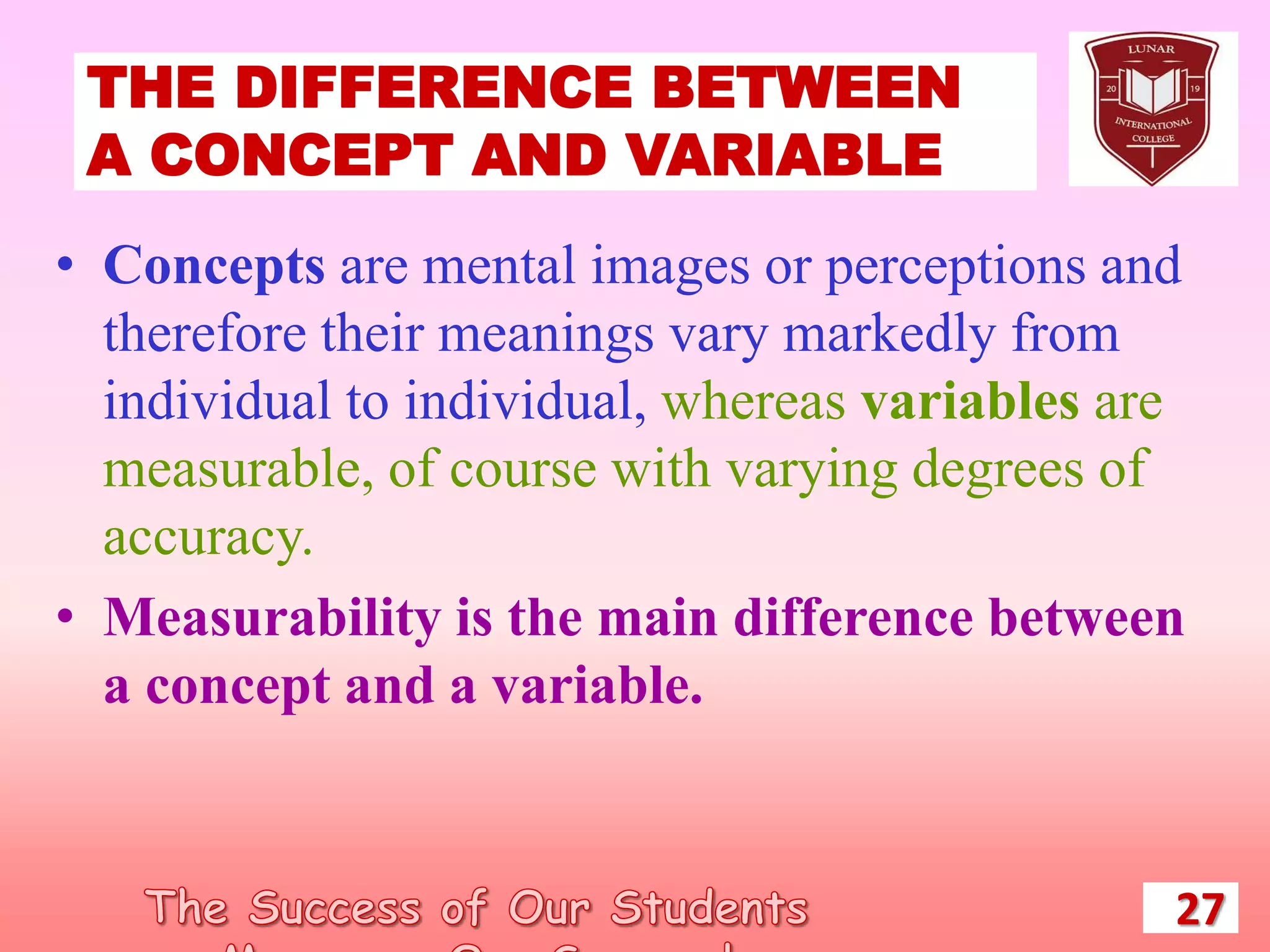

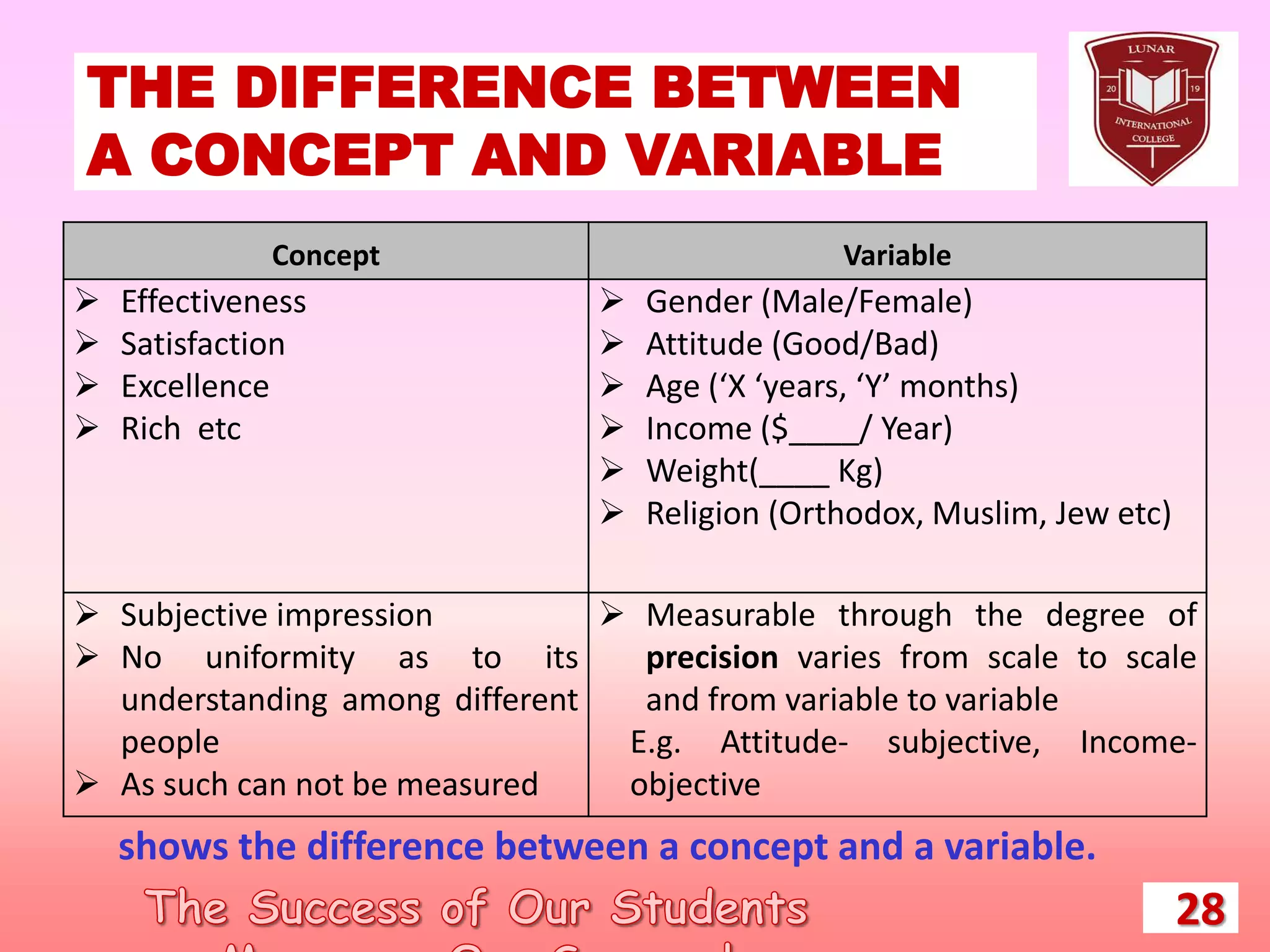

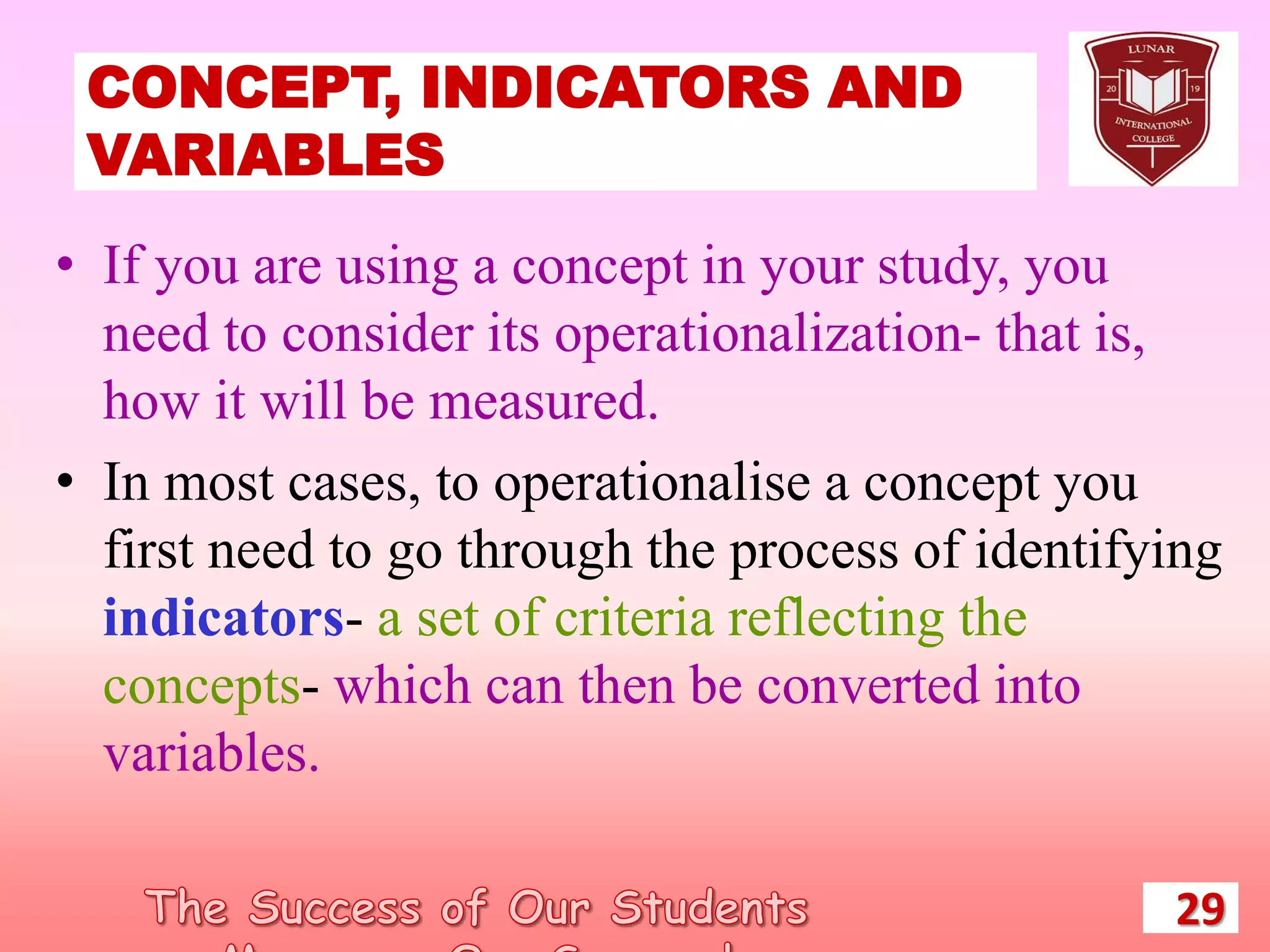

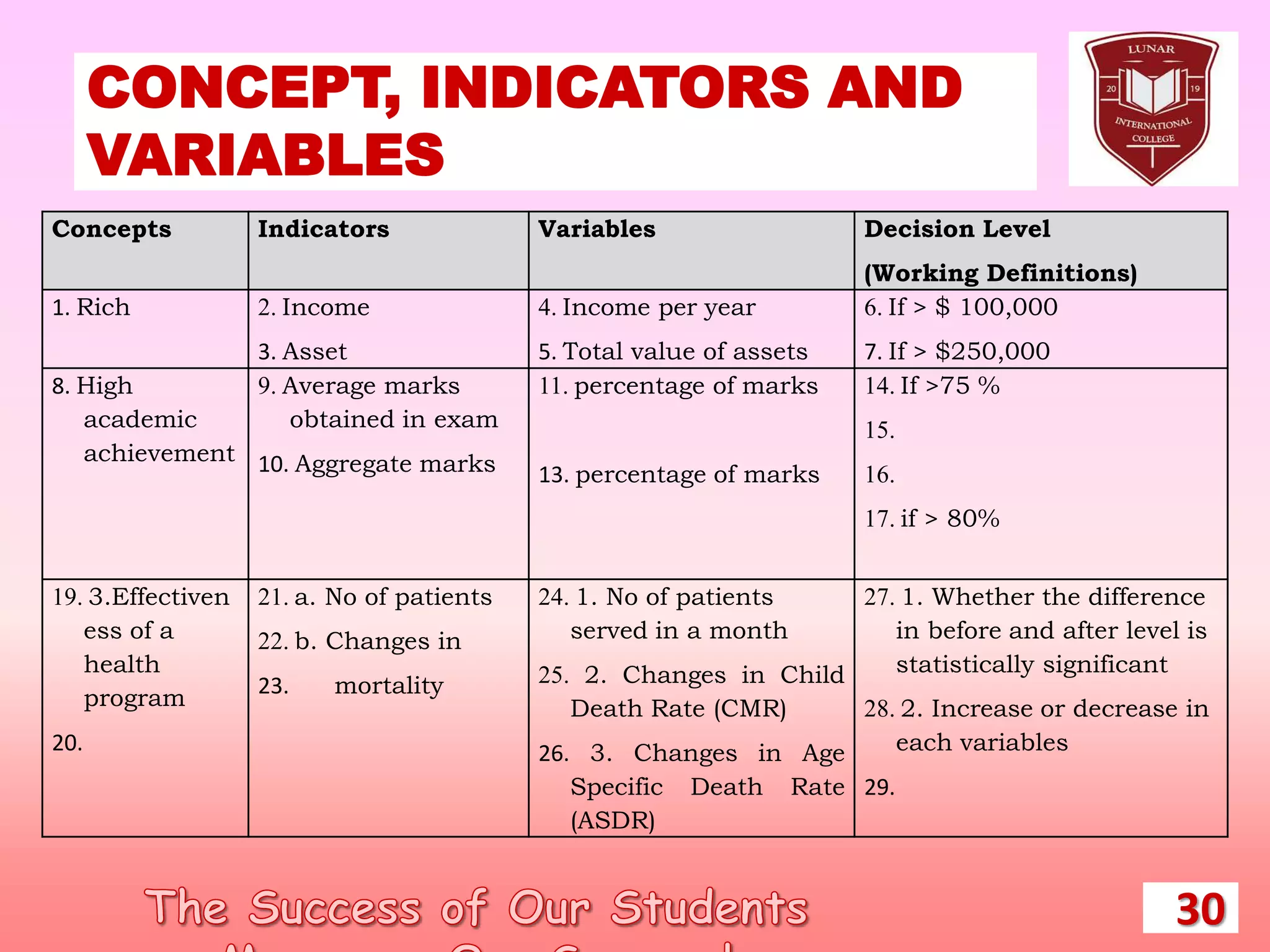

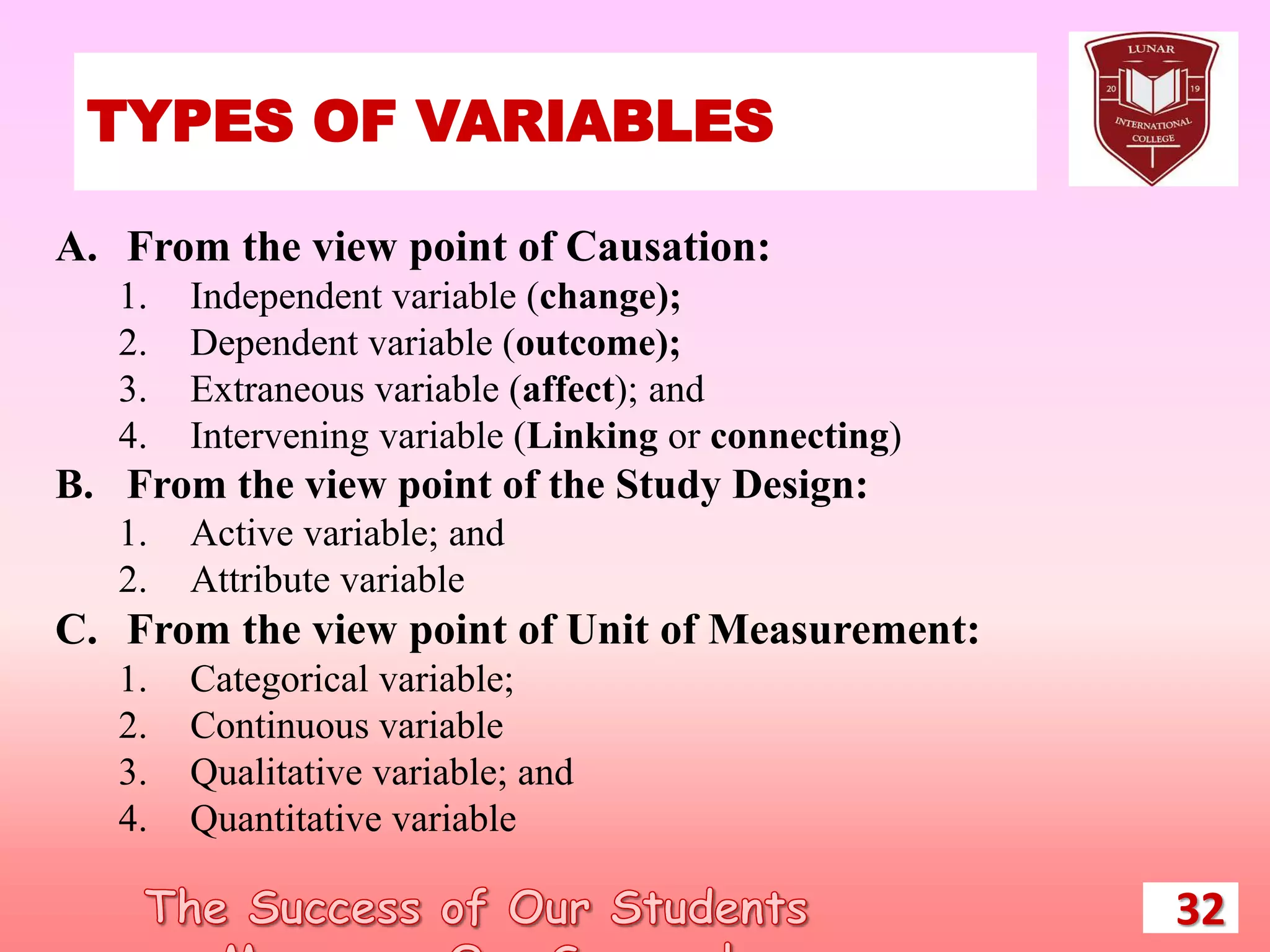

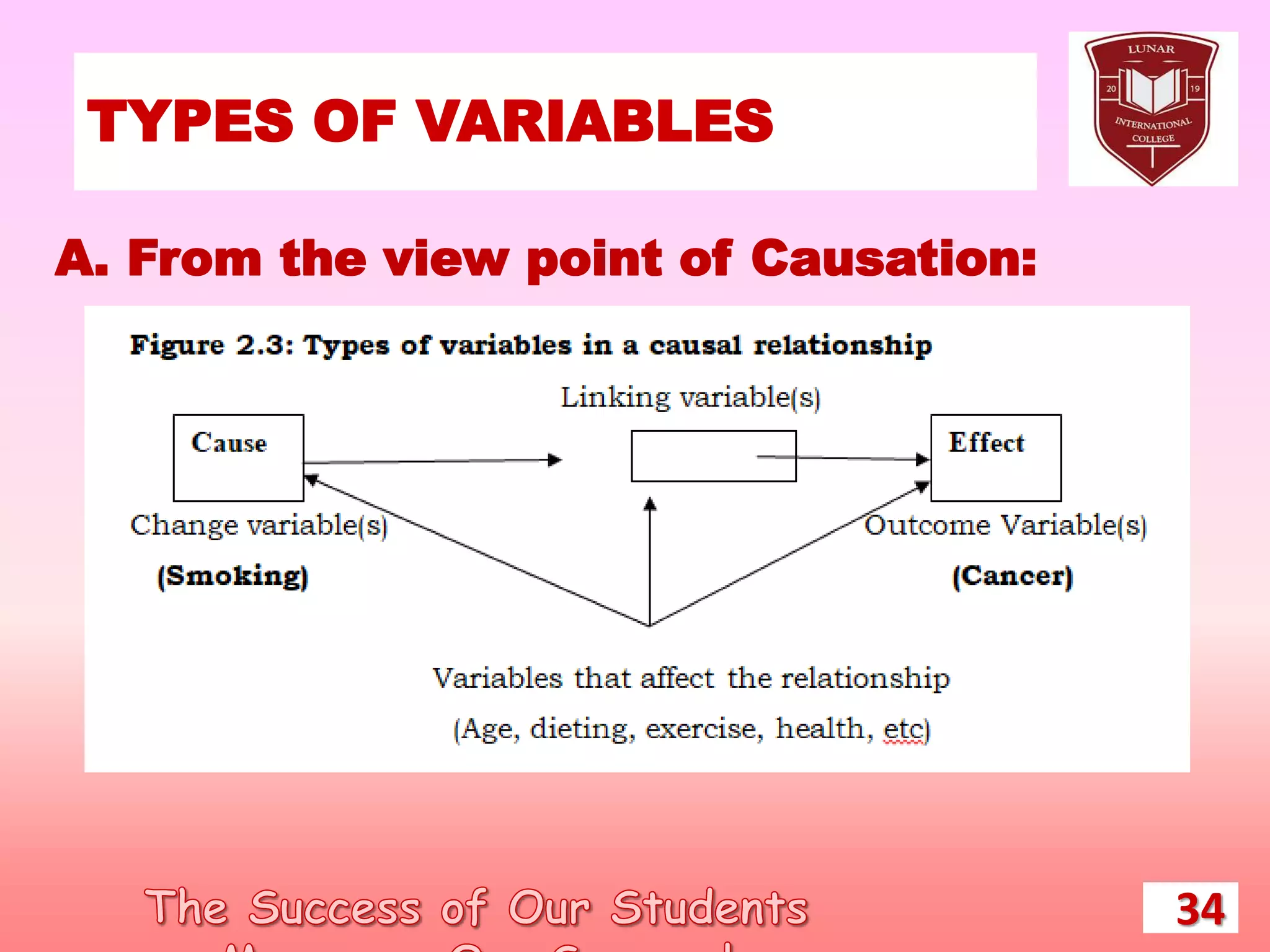

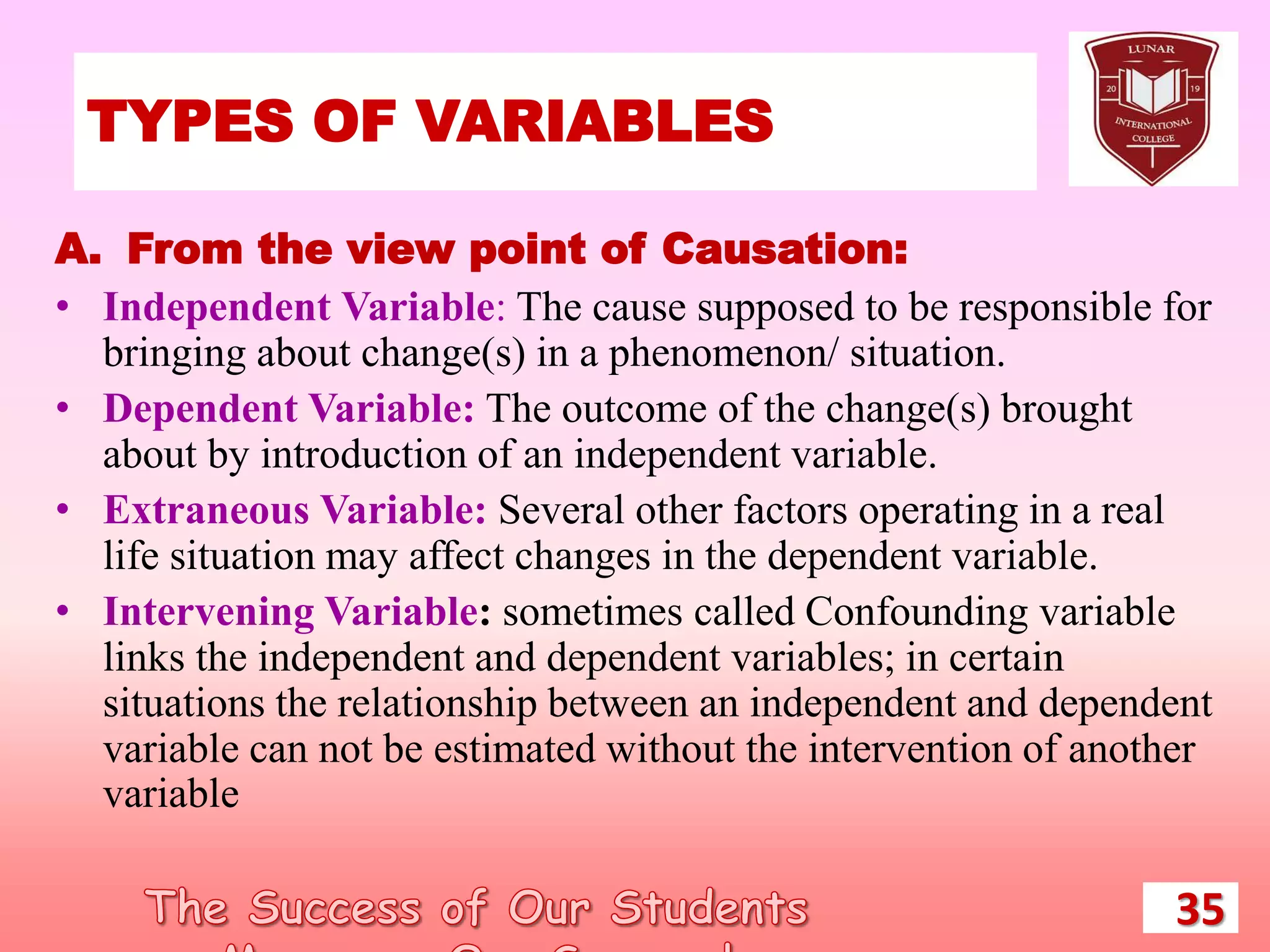

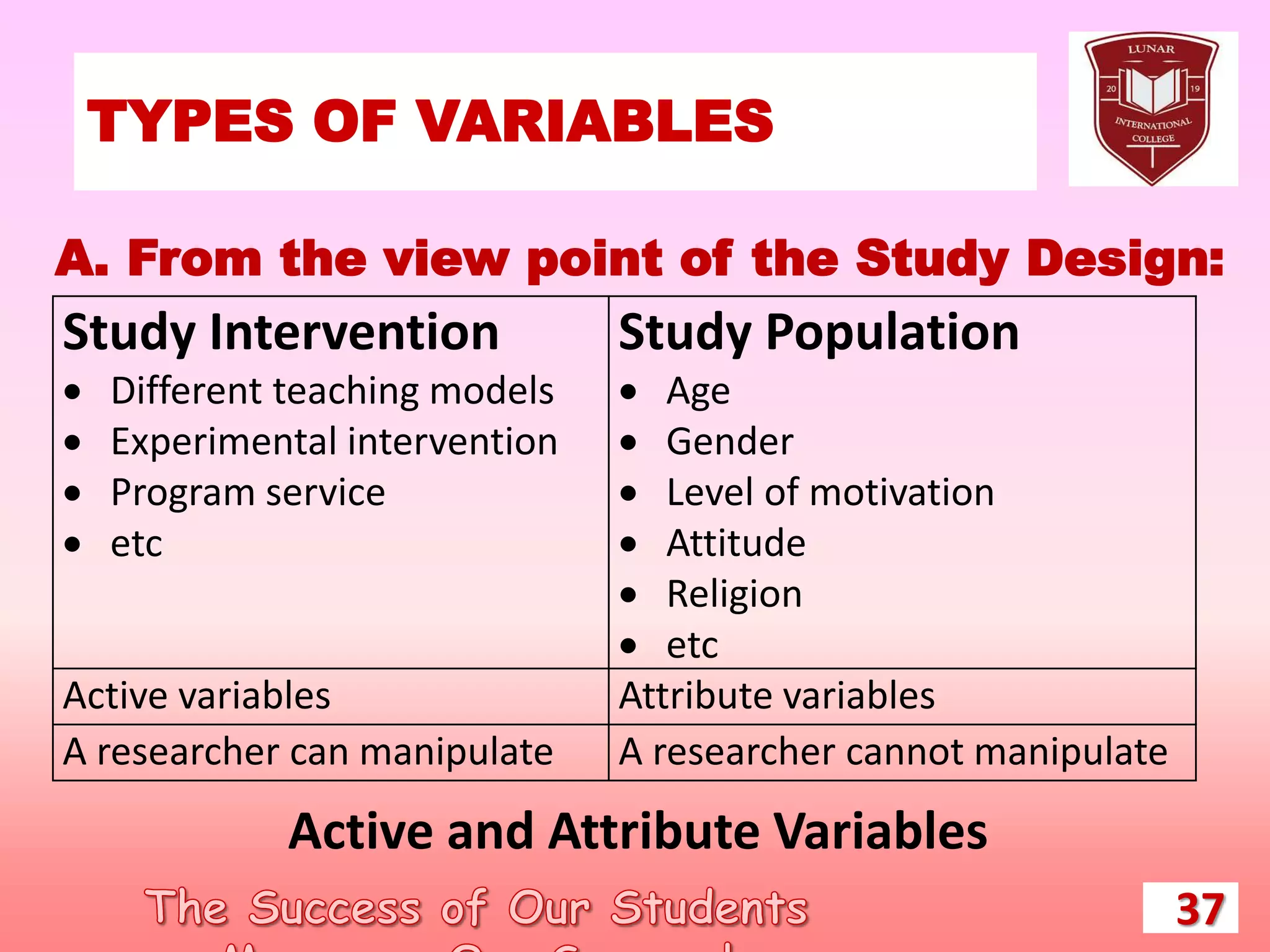

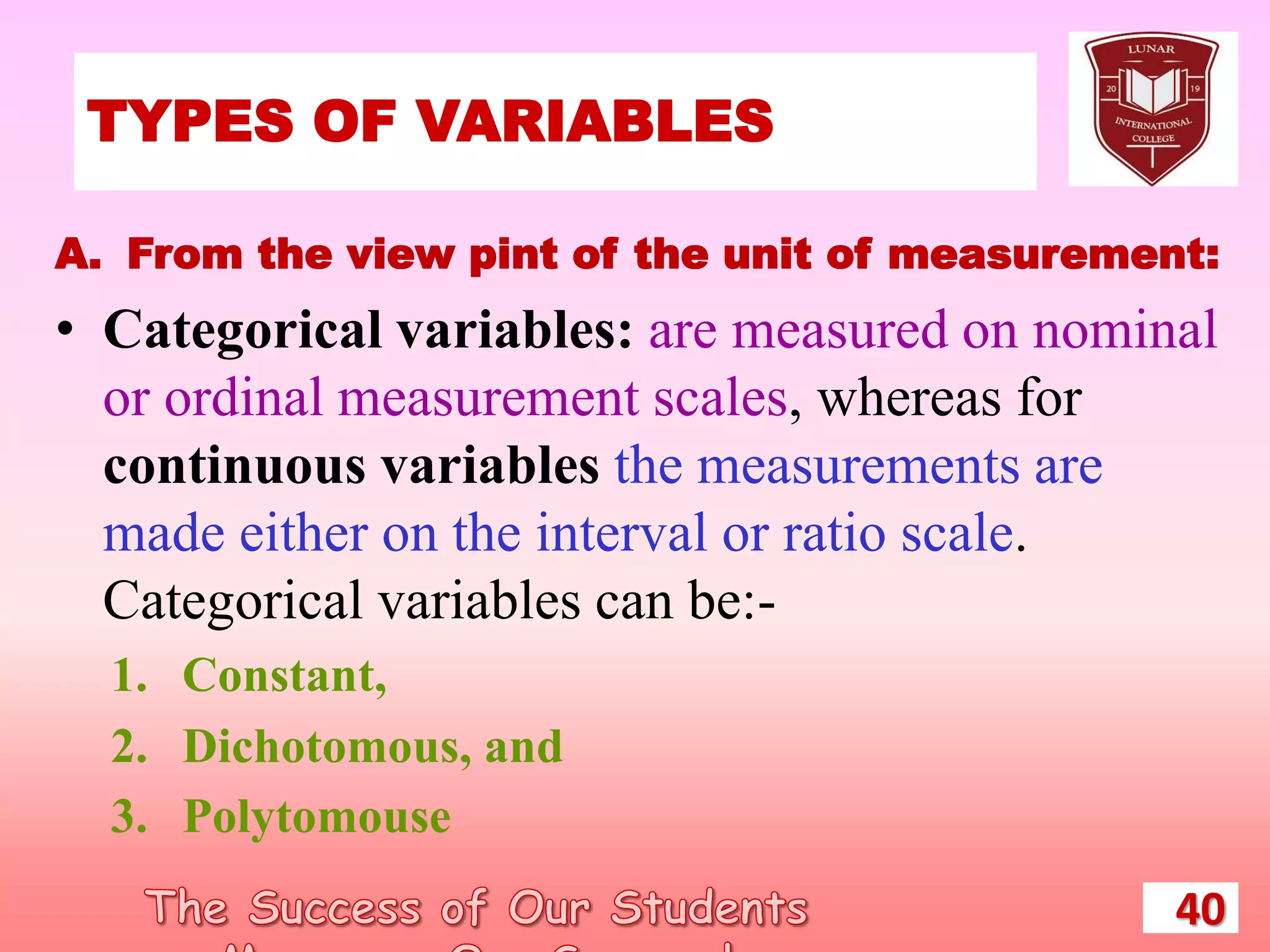

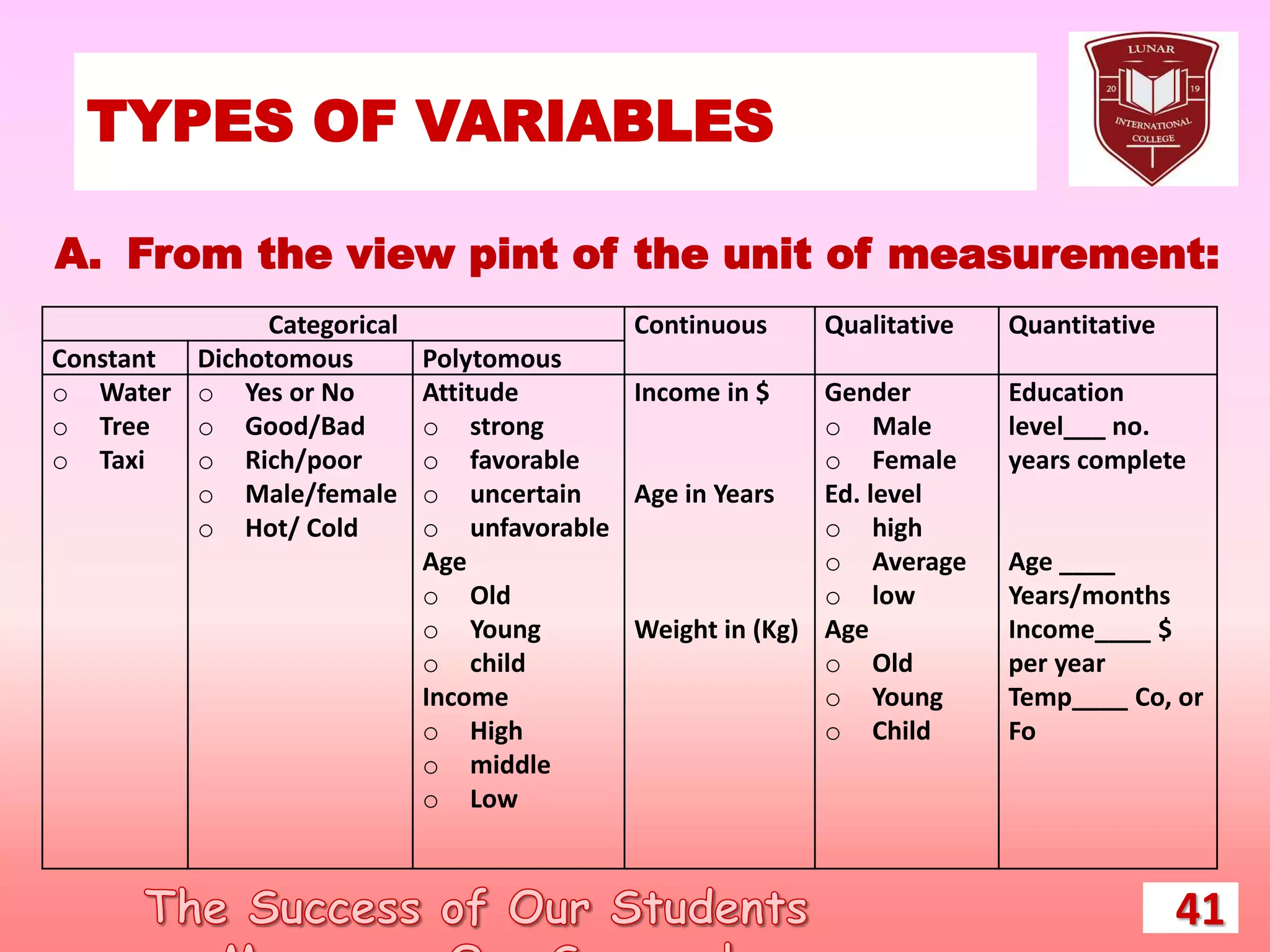

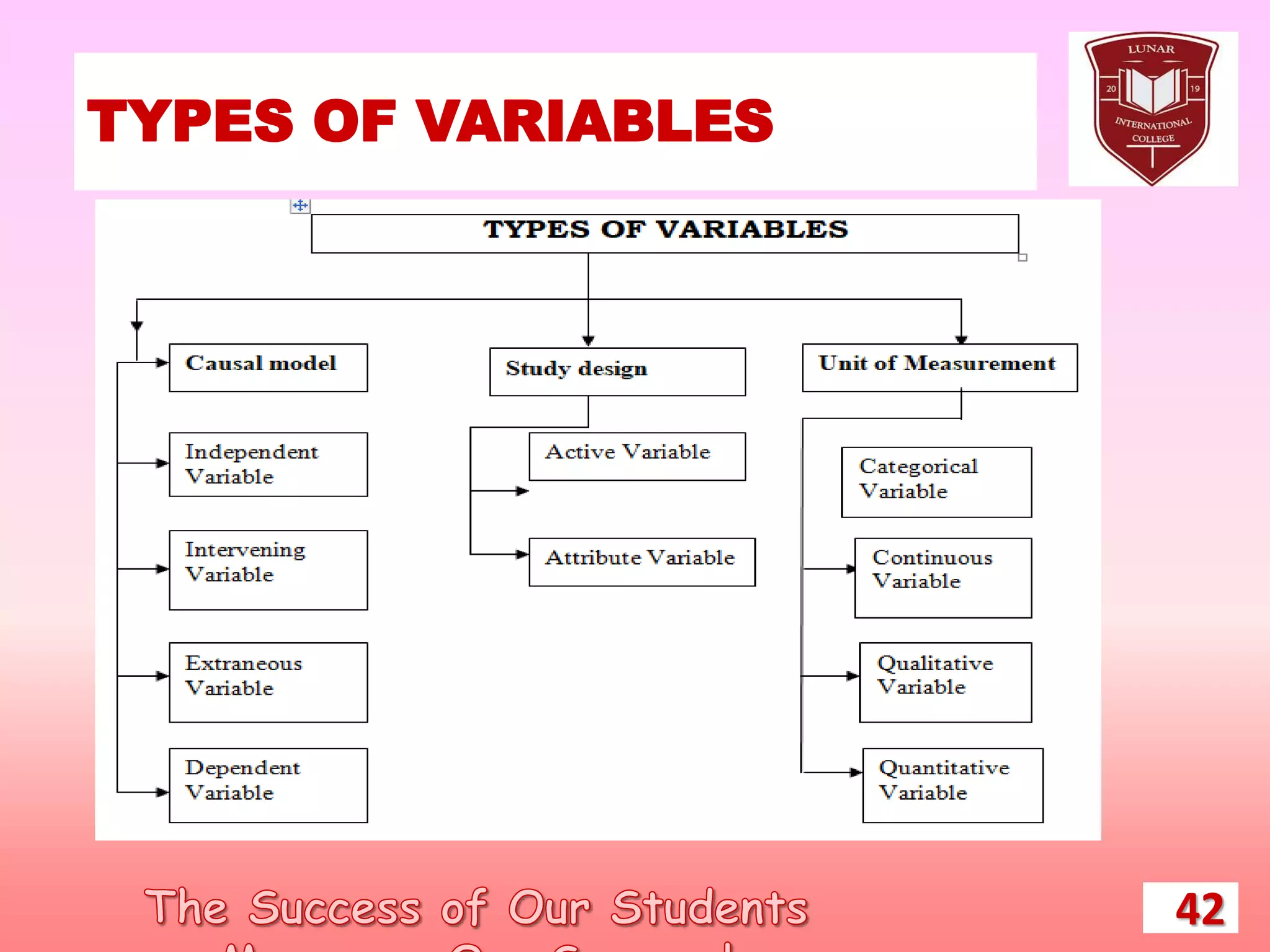

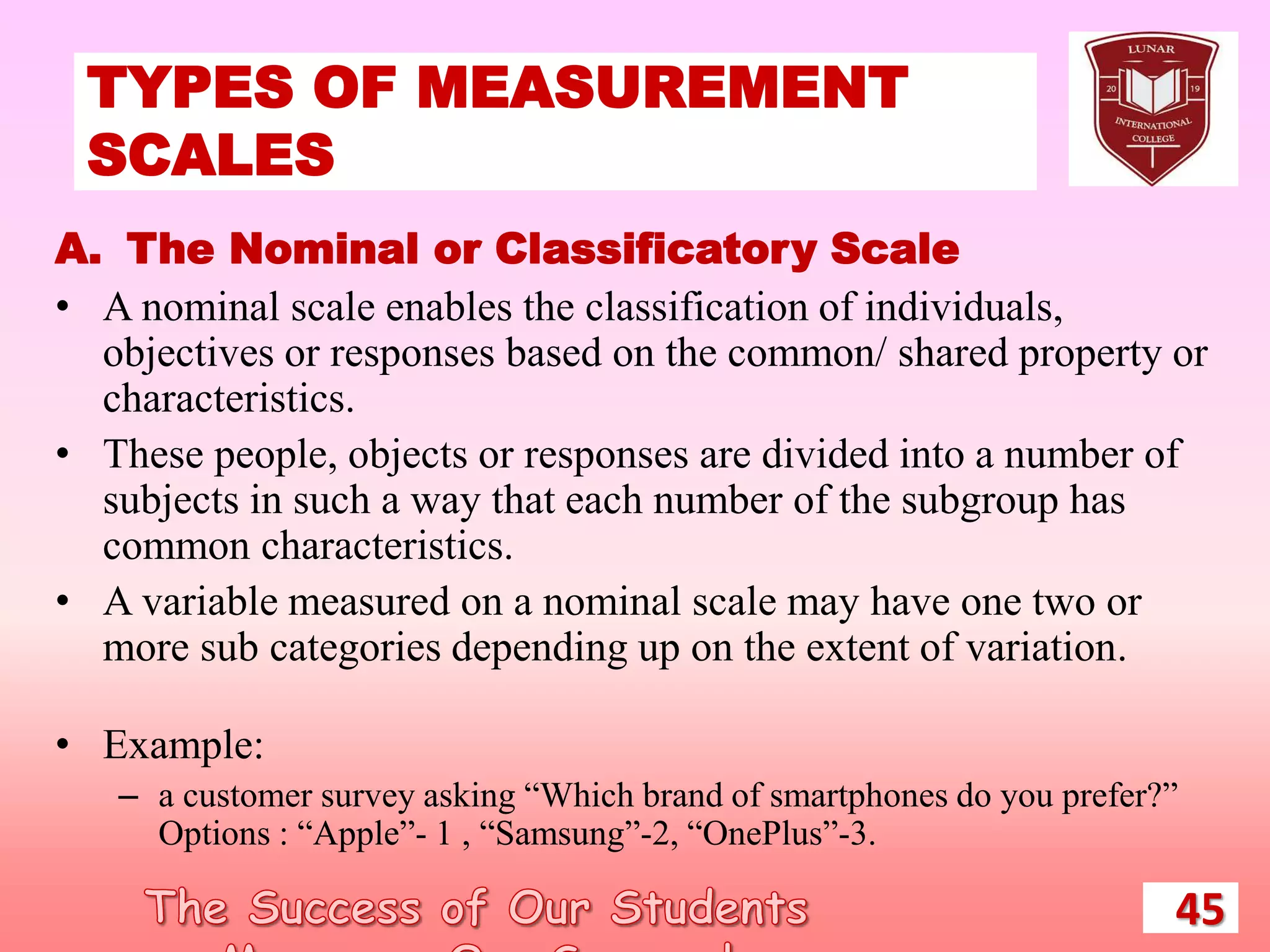

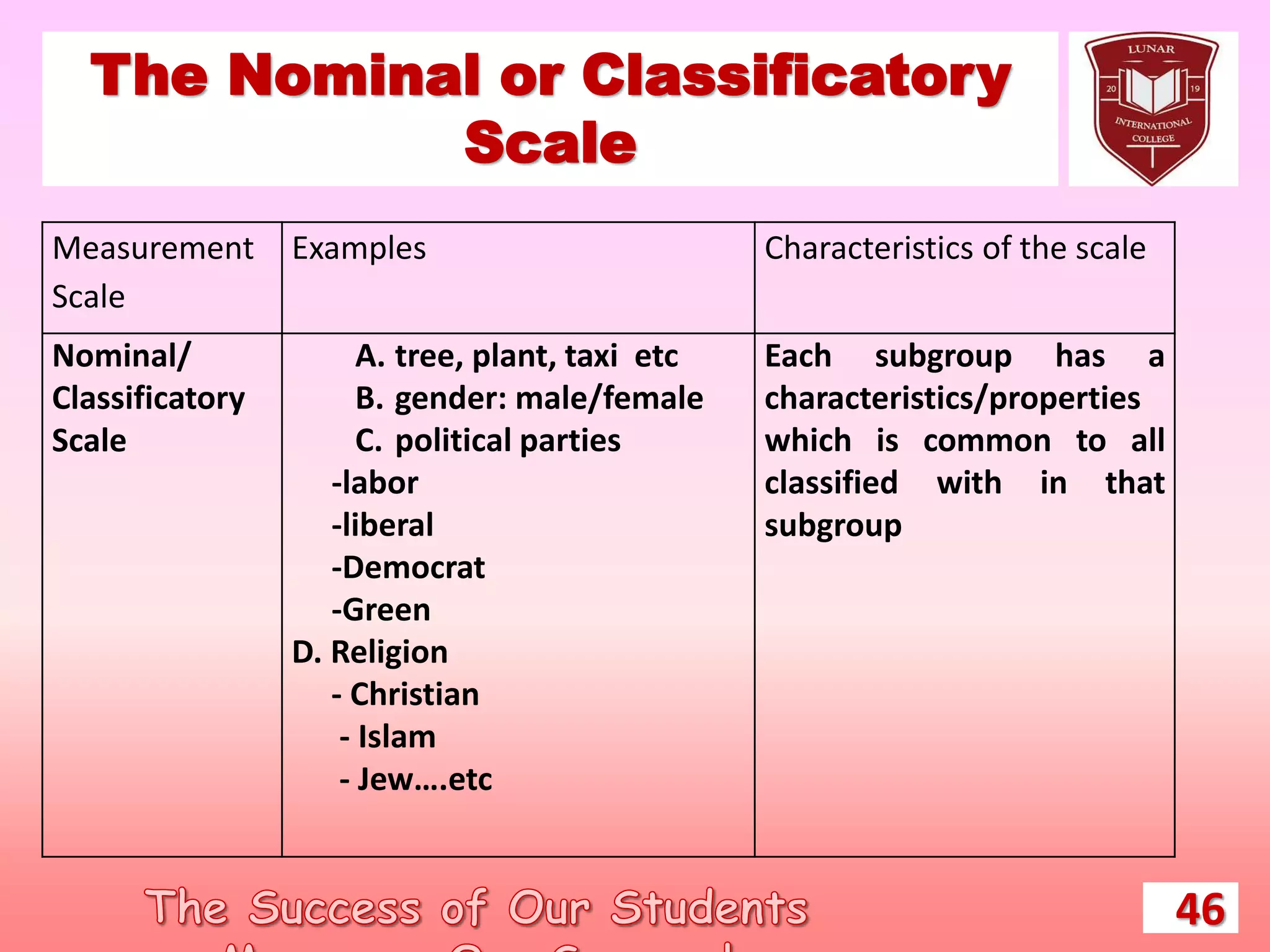

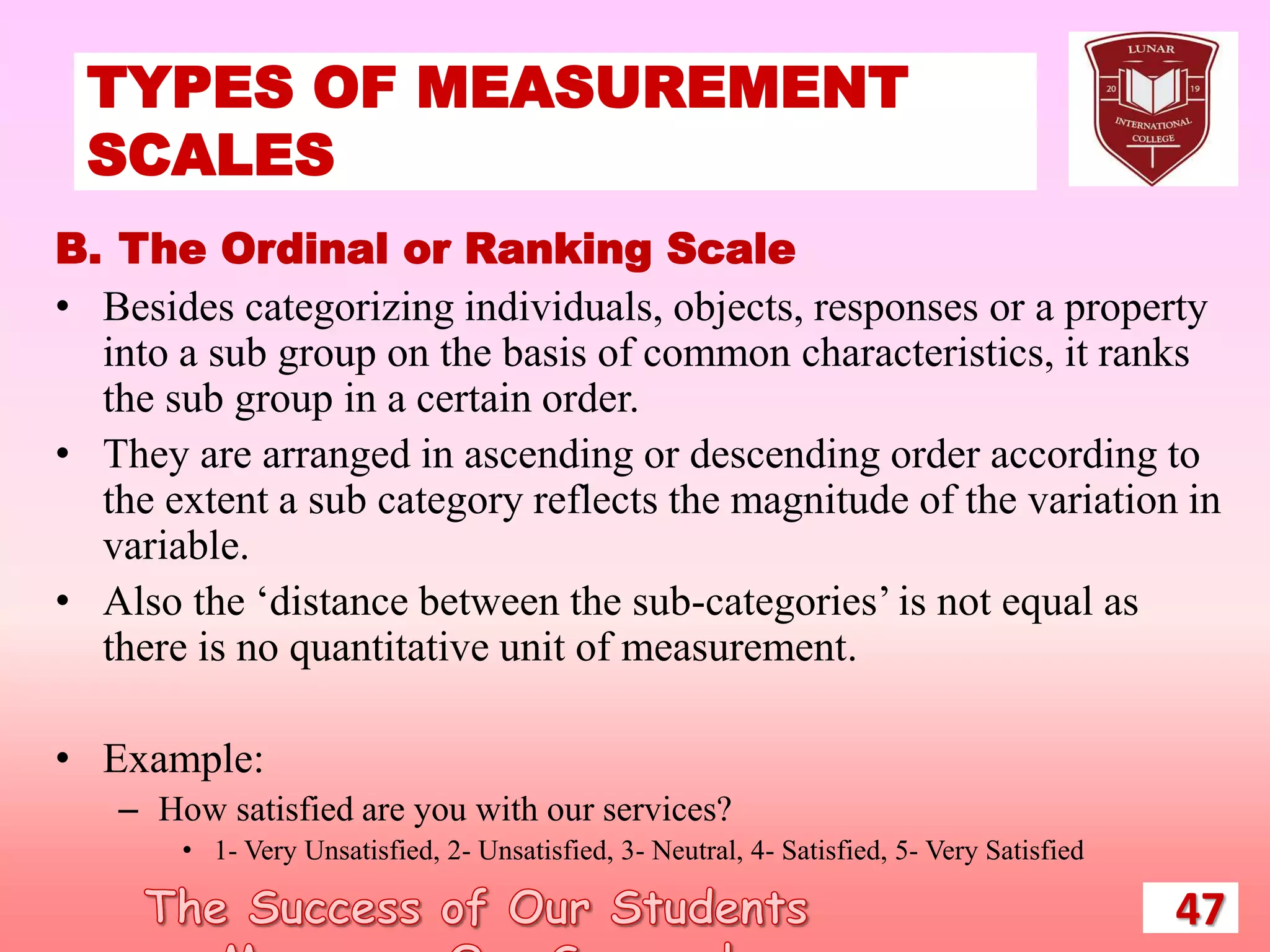

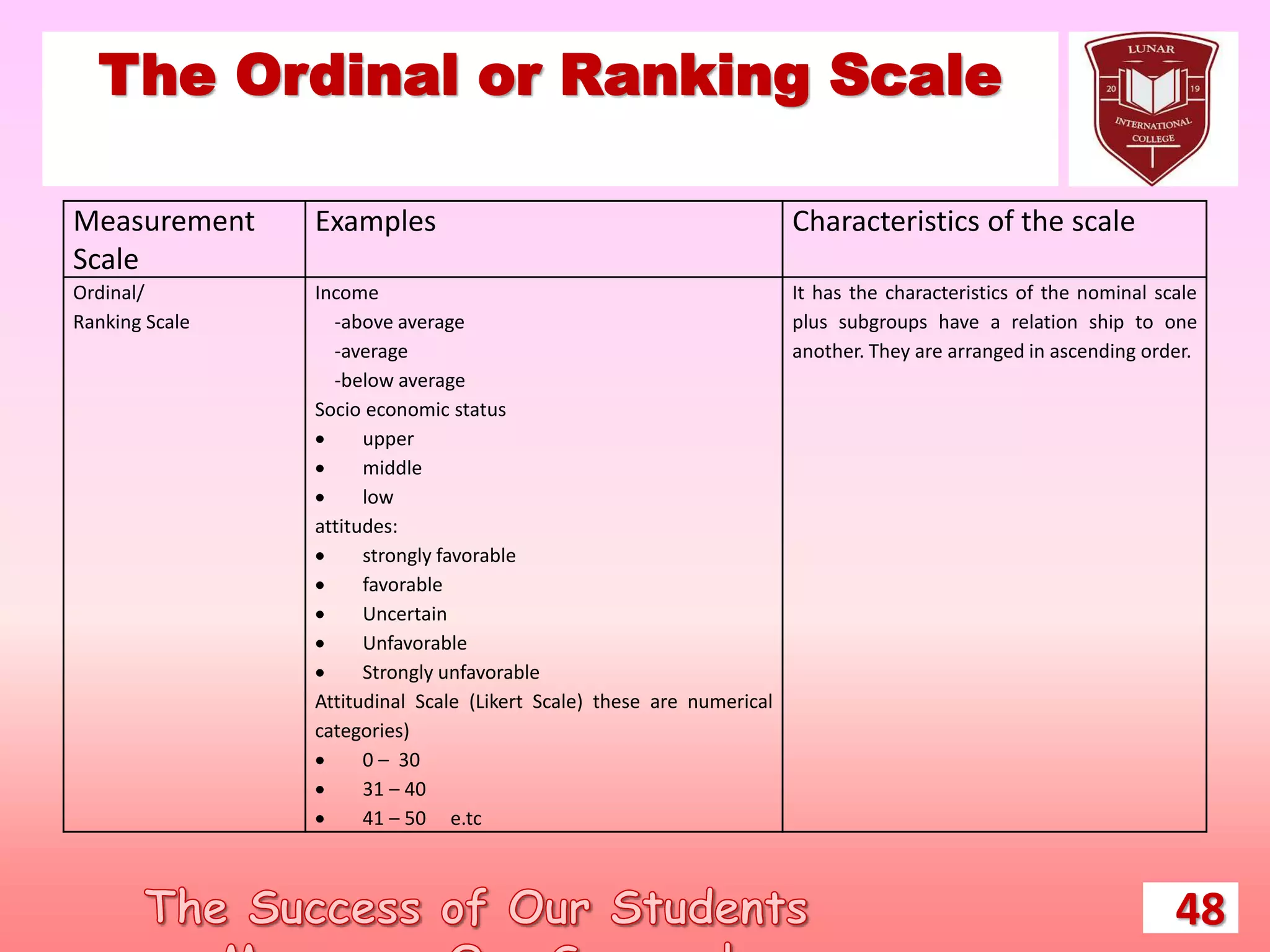

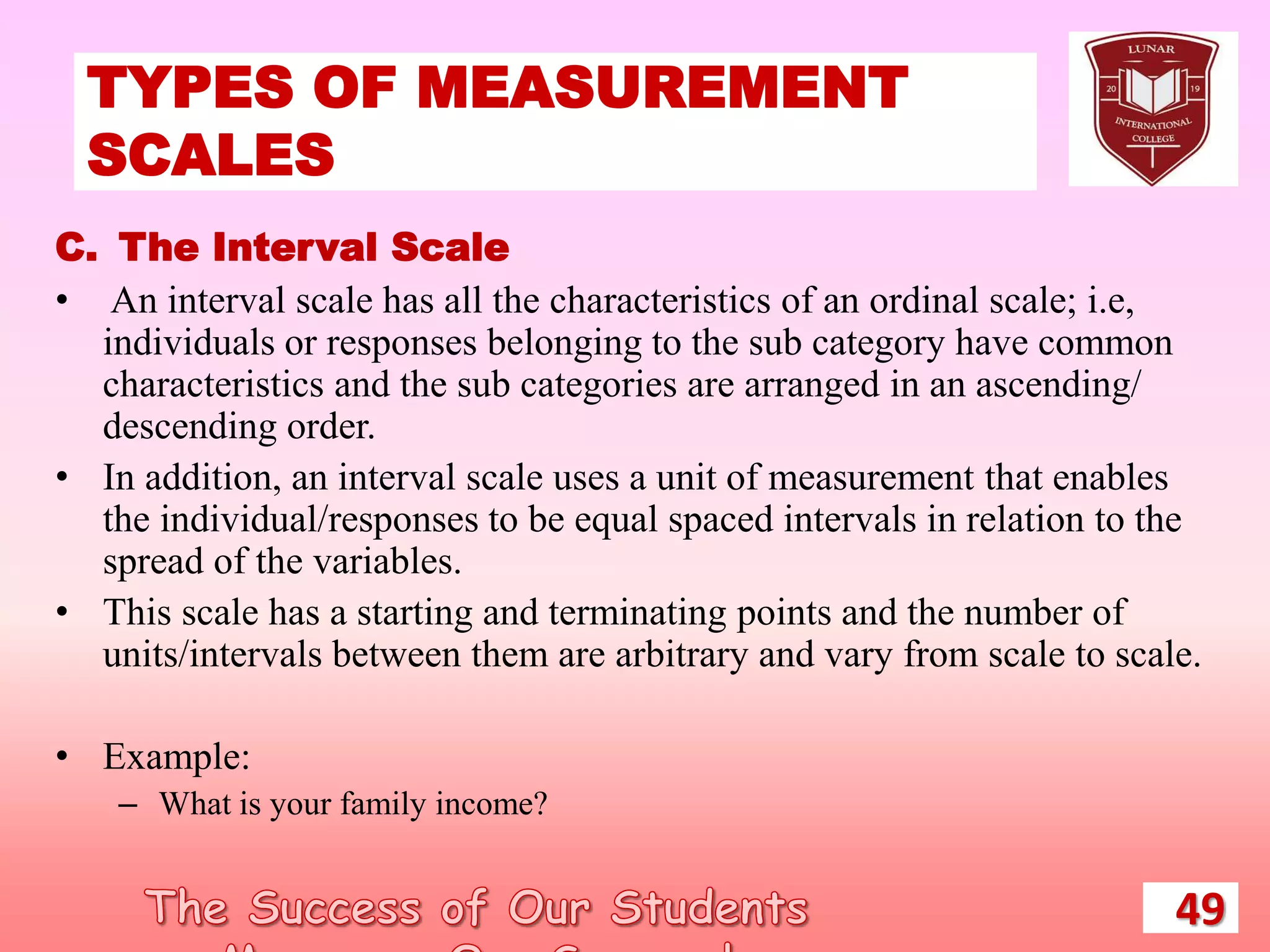

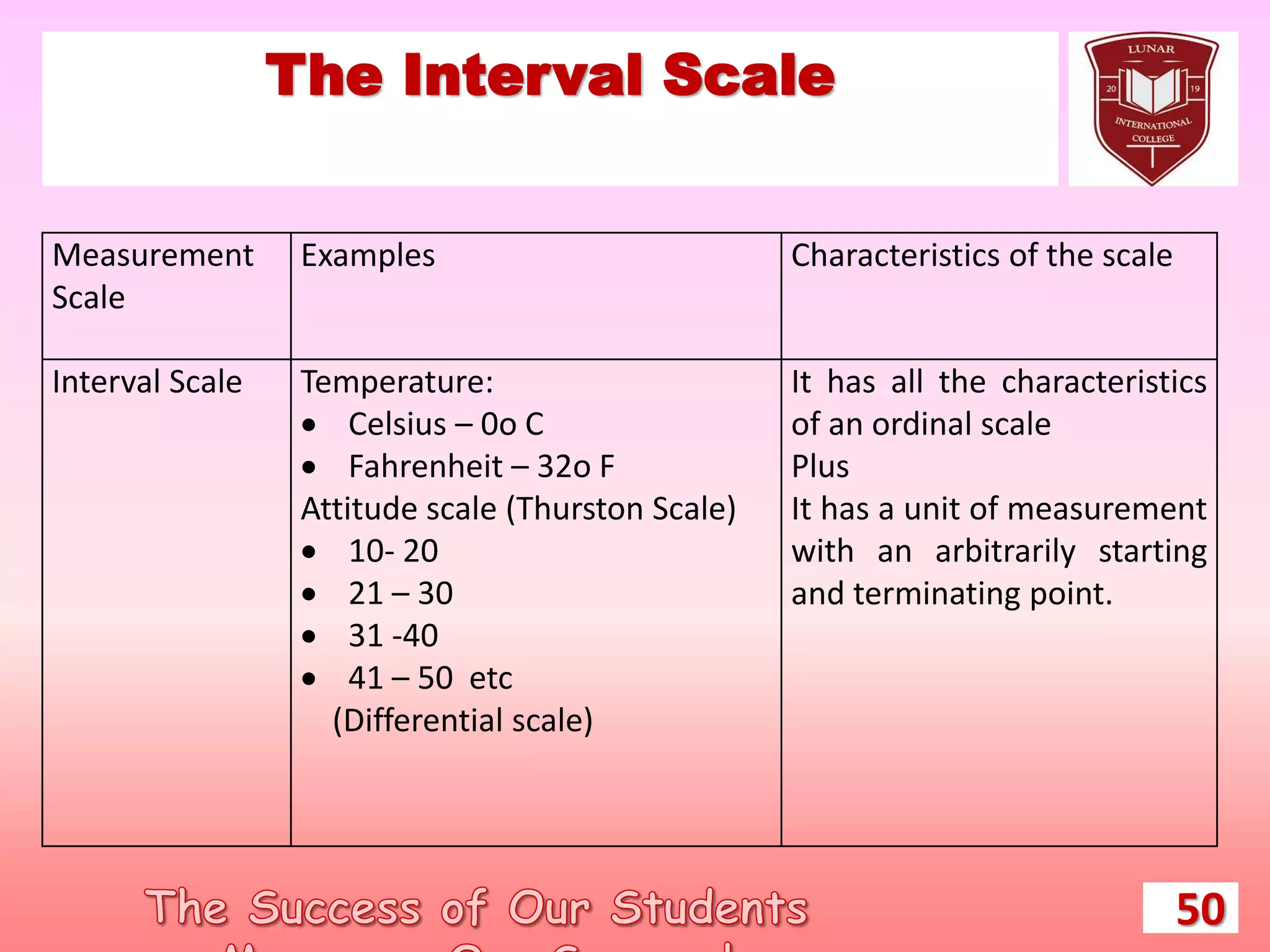

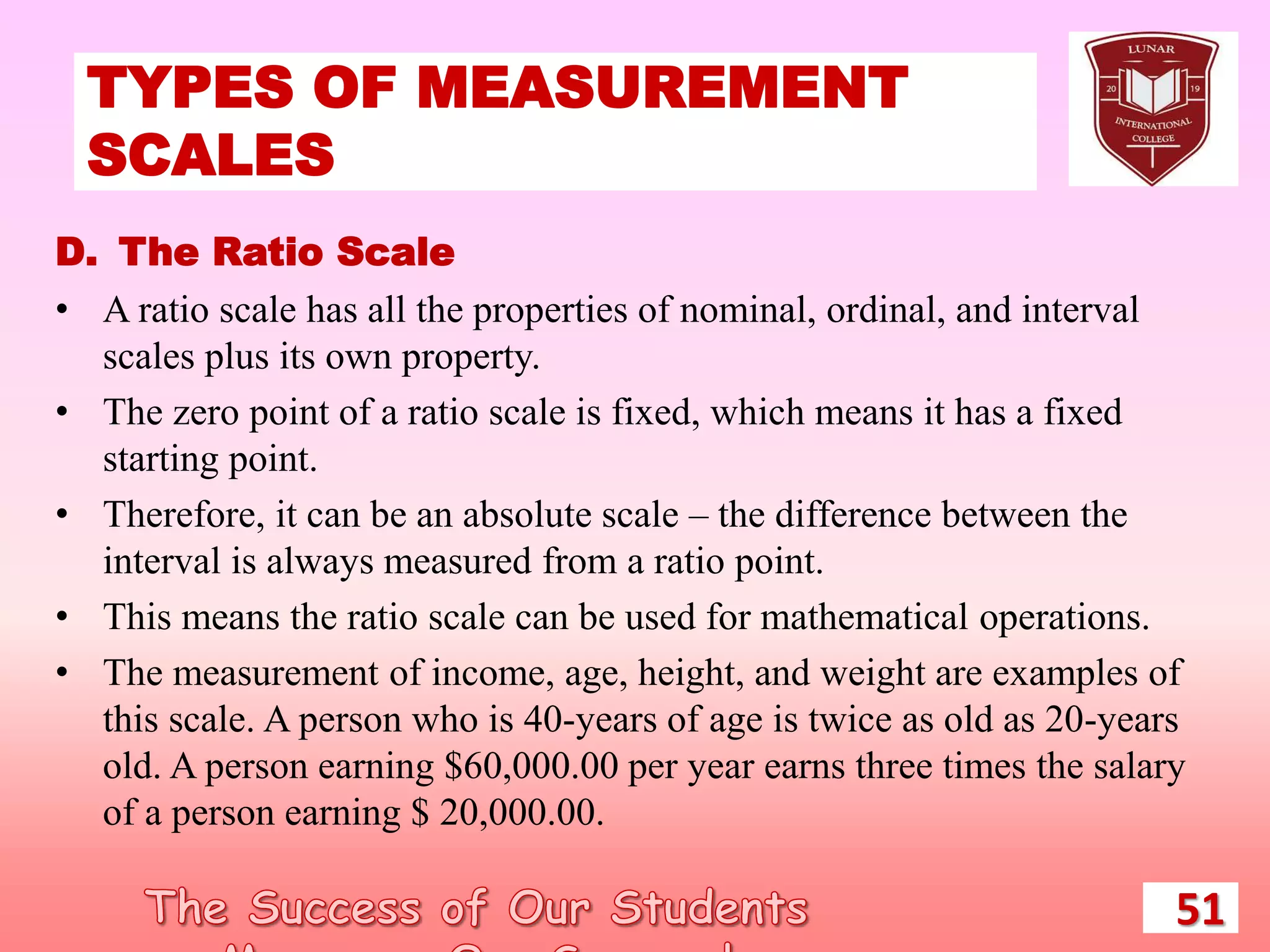

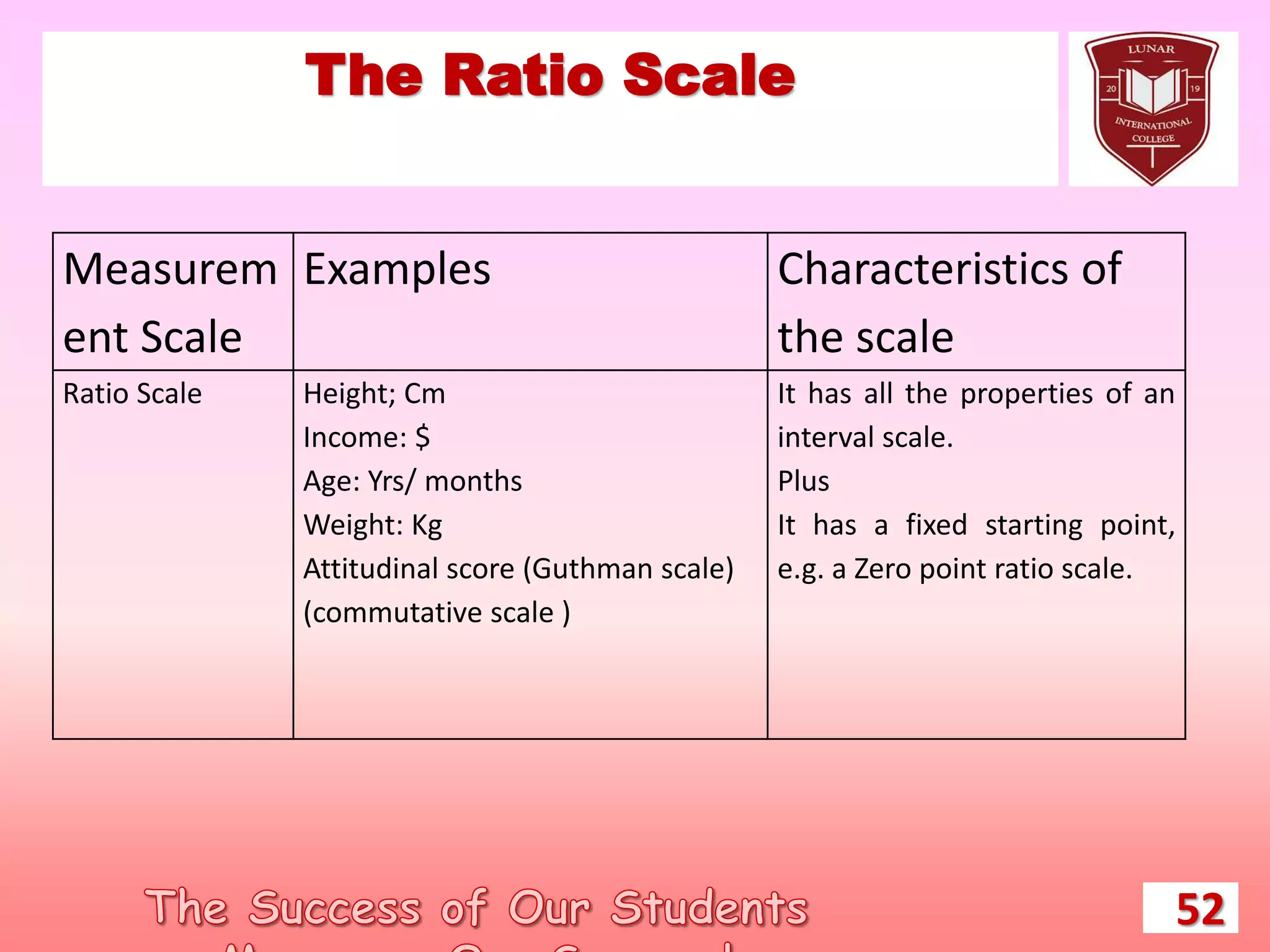

This document discusses formulating a research problem. It begins by defining what constitutes a research problem and providing examples of questions and assumptions that can become research problems. It emphasizes that clearly formulating the research problem is the most important first step. Aspects of a good research problem like objectives and variables are discussed. The importance of operationalizing concepts and variables is explained. Different types of variables from the perspective of causation, study design, and unit of measurement are outlined. Finally, the four types of measurement scales used in social sciences are defined.