The document discusses cervical spine injuries, including:

1. The cervical spine consists of 7 vertebrae that support the head and allow movement while protecting the spinal cord.

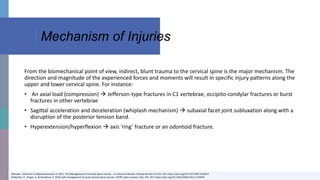

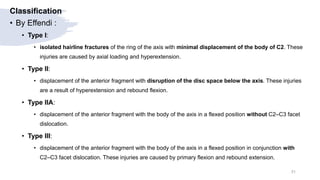

2. Cervical spine injuries commonly result from motor vehicle accidents, falls, sports, or assaults and can cause fractures, dislocations, or ligament damage in the upper or lower cervical spine.

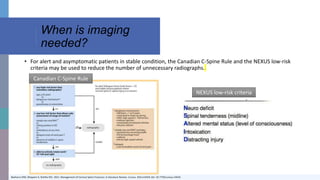

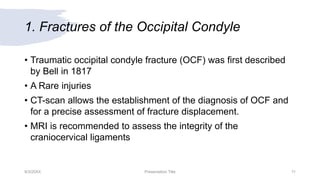

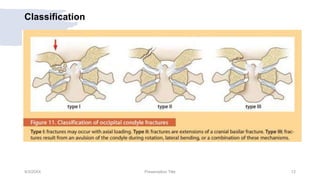

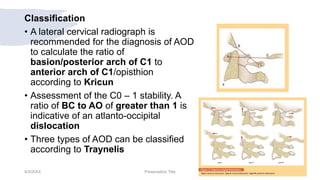

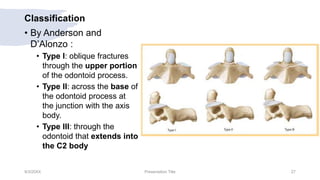

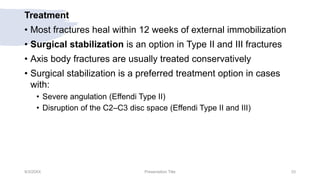

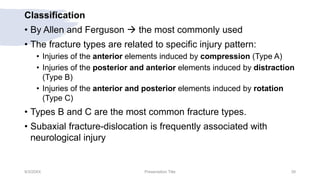

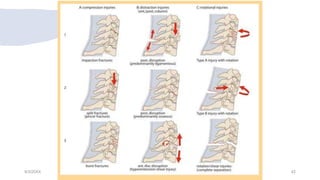

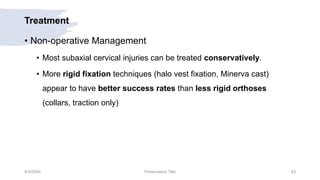

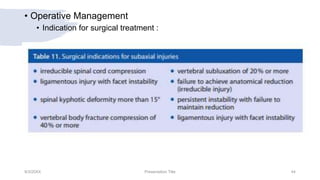

3. Injuries are classified based on their location and mechanism, and treatment may involve immobilization, traction, surgery to stabilize and fuse vertebrae, or a combination depending on the severity and location of the injury. Precise imaging is important to diagnose injuries and guide appropriate treatment.