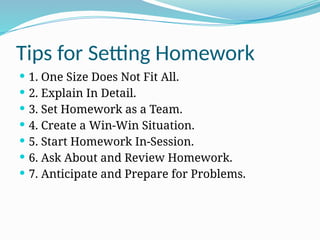

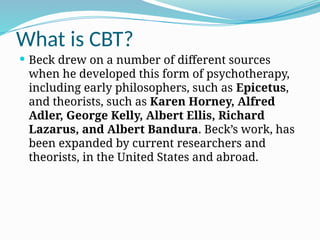

The document outlines the principles and processes of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) as developed by Aaron T. Beck in the 1960s, emphasizing the connection between thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. It details the cognitive model, various forms of CBT, the importance of therapeutic relationships, and practical techniques for assessment and intervention. Additionally, it presents empirical evidence supporting the efficacy of CBT for a wide range of psychiatric and psychological issues.

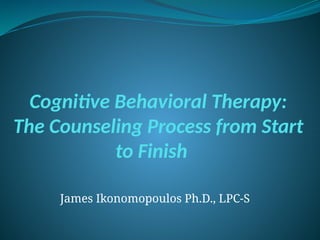

![What is the Theory of CBT?

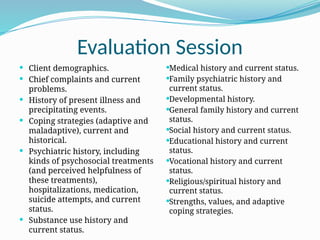

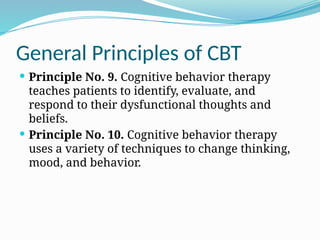

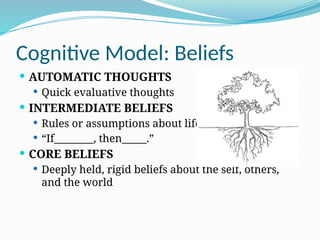

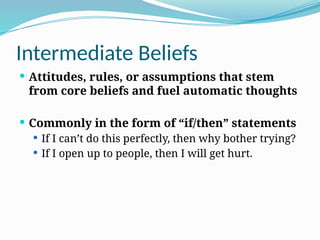

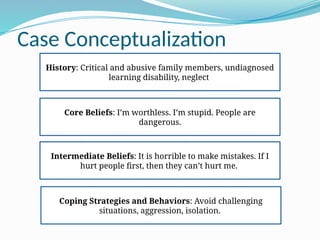

For lasting improvement in patients’ mood and behavior,

cognitive therapists work at a deeper level of cognition: patients’

basic beliefs about themselves, their world, and other people.

Modification of their underlying dysfunctional beliefs produces

more enduring change. For example, if you continually

underestimate your abilities, you might have an underlying

belief of incompetence.

Modifying this general belief (i.e., seeing yourself in a more

realistic light as having both strengths and weaknesses) can alter

your perception of specific situations that you encounter daily.

You will no longer have as many thoughts with the theme, “I can’t

do anything right.” Instead, in specific situations where you make

mistakes, you will probably think, “I’m not good at this [specific

task].”](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cbt-refresher-250125234009-cad81aa9/85/cbt-refreshervvvvvvvvvvvvvbbbbbbbbbbb-pptx-14-320.jpg)

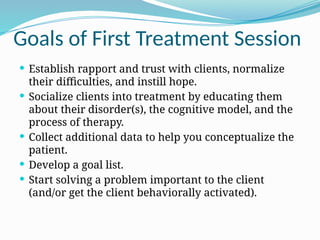

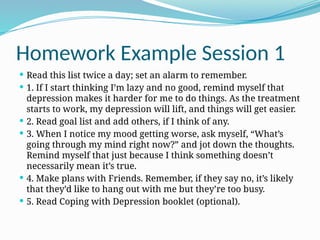

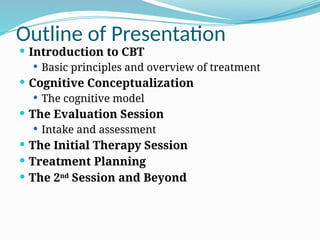

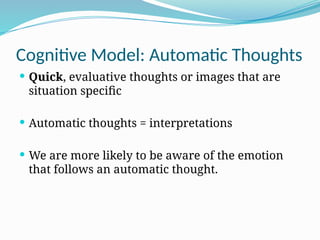

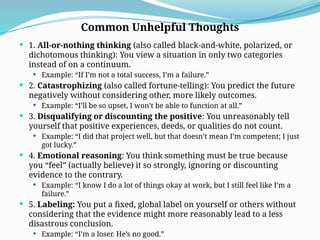

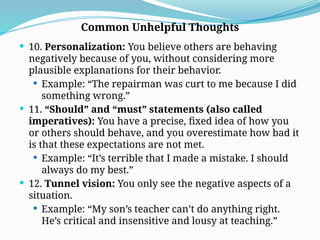

![ 6. Magnification/minimization: When you evaluate yourself,

another person, or a situation, you unreasonably magnify the

negative and/or minimize the positive.

Example: “Getting a mediocre evaluation proves how

inadequate I am. Getting high marks doesn’t mean I’m

smart.”

7. Mental filter (also called selective abstraction): You pay

undue attention to one negative detail instead of seeing the

whole picture.

Example: “Because I got one low rating on my evaluation

[which also contained several high ratings] it means I’m

doing a lousy job.”

8. Mind reading: You believe you know what others are

thinking, failing to consider other, more likely possibilities.

Example: “He thinks that I don’t know the first thing about

this project.”

9. Overgeneralization: You make a sweeping negative

Common Unhelpful Thoughts](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cbt-refresher-250125234009-cad81aa9/85/cbt-refreshervvvvvvvvvvvvvbbbbbbbbbbb-pptx-38-320.jpg)

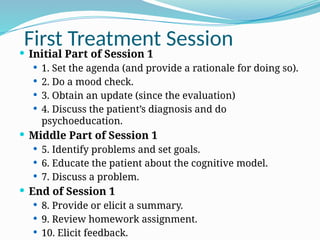

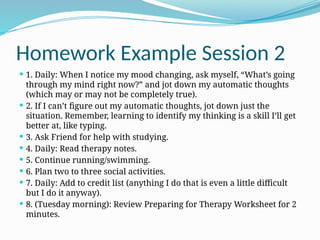

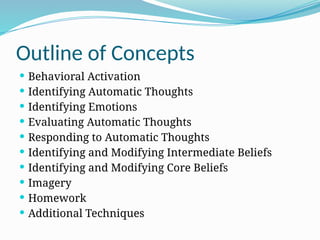

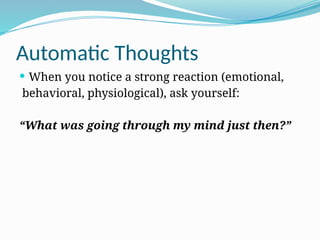

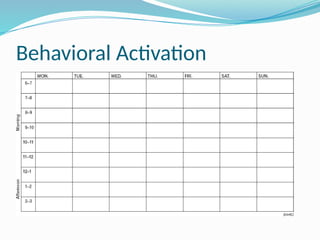

![Behavioral Activation

Situation: Thinking about initiating an activity

[Common] Automatic thoughts: “I’m too tired. I won’t

enjoy it. My friends won’t want to spend time with me. I

won’t be able to do it. Nothing can help me feel better.”

[Common] Emotional reactions: Sadness, anxiety,

hopelessness

[Common] Behavior: Remain inactive.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cbt-refresher-250125234009-cad81aa9/85/cbt-refreshervvvvvvvvvvvvvbbbbbbbbbbb-pptx-49-320.jpg)

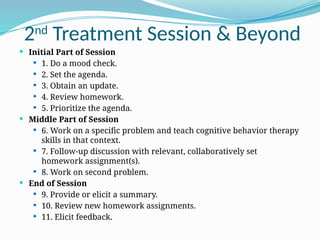

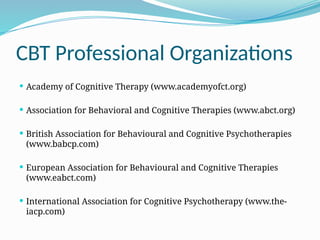

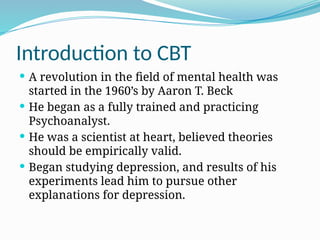

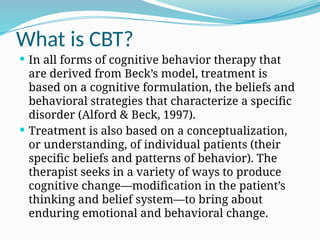

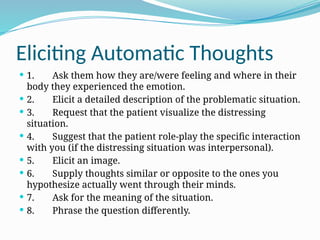

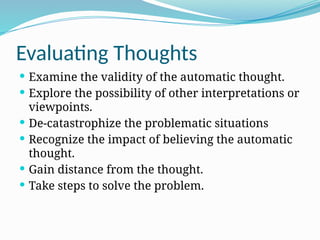

![Evaluating Thoughts

1. What is the evidence that supports this idea?

What is the evidence against this idea?

2. Is there an alternative explanation or viewpoint?

3. What is the worst that could happen (if I’m not already

thinking the worst)? If it happened, how could I cope?

What is the best that could happen?

What is the most realistic outcome?

4. What is the effect of my believing the automatic thought?

What could be the effect of changing my thinking?

5. What would I tell____________[a specific friend or family

member] if he or she were in the same situation?

6. What should I do?](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cbt-refresher-250125234009-cad81aa9/85/cbt-refreshervvvvvvvvvvvvvbbbbbbbbbbb-pptx-52-320.jpg)