This document presents the crystal structure of mature apo-caspase-6, an enzyme involved in neurodegenerative diseases. The structure reveals the canonical caspase conformation, contrasting with a previous structure of apo-caspase-6 that showed a noncanonical conformation. The authors believe the previous structure represented an inactive pH-dependent form. Comparison to other caspase structures allows visualization of loop rearrangements upon ligand binding. This new structure provides insight into the conformational dynamics of caspase-6.

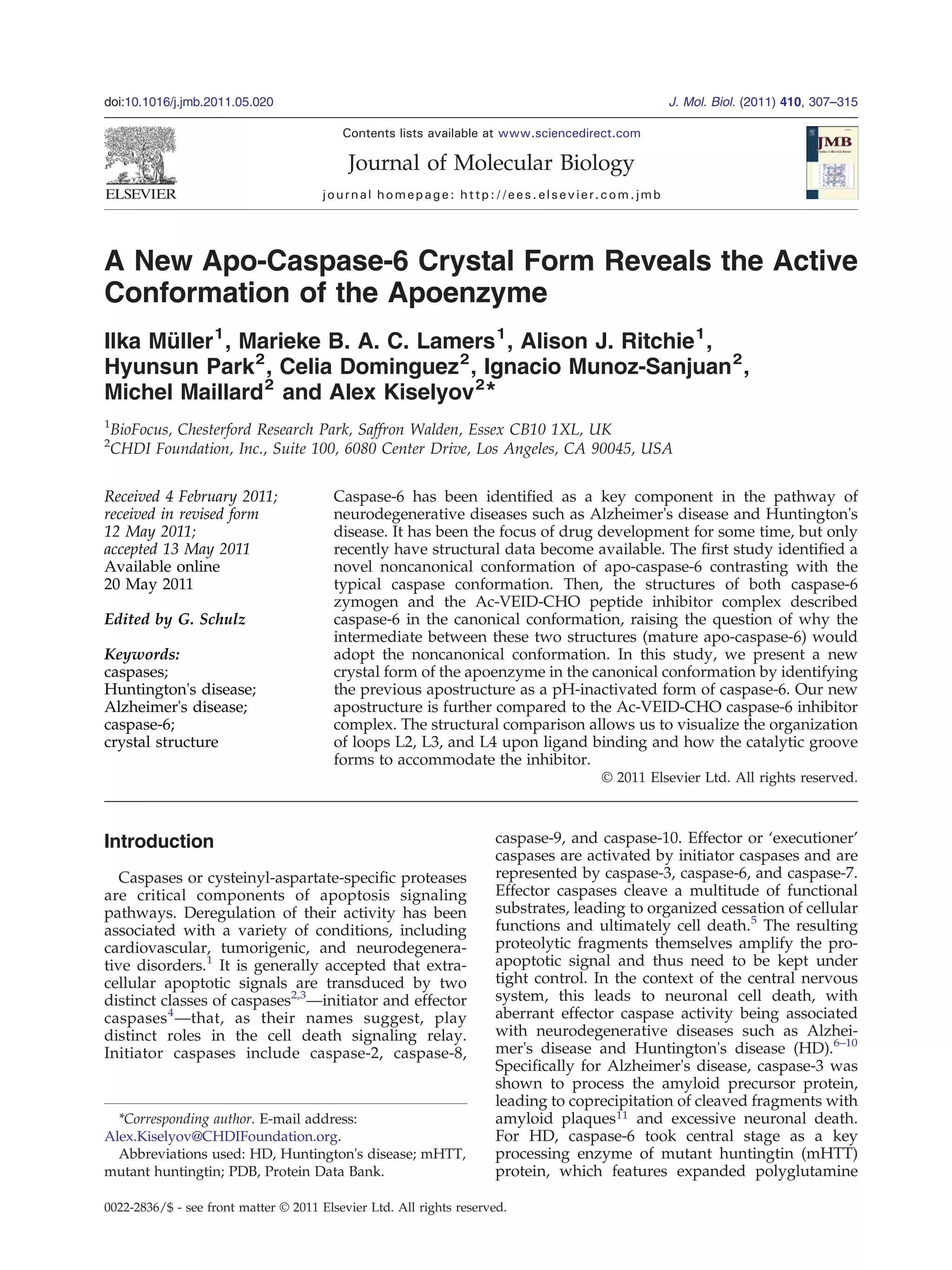

![the tetramer consisting of chains A/B and C/D (Fig.

1a). The overall topology of caspase-6 at pH 7.4

closely resembles the caspase-6 zymogen structure

[Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID: 3NR2; RMSD of 0.74 Å

for 205 Cα

atoms within the p20/p10 dimer; Fig. 1b]

and the mature ligand-free caspase-7 (PDB ID: 1K86;

196 topologically equivalent Cα

atoms within the

p20/p10 dimer superimposing with an RMSD of

0.85 Å; Fig. 1c), with a central six-stranded mixed

β-sheet flanked by five α-helices. It is distinct from

the structure reported for caspase-6 at pH 4.6 (PDB

ID: 2WDP; RMSD of 3.3 Å for 203 Cα

atoms within

the p20/p10 dimer; Fig. 1d), leading to our

hypothesis that crystallization of caspase-6 at low

pH likely sequestered a pH-inactivated form, which

had not been observed when caspase-3 or caspase-7

was crystallized at pH b5 (i.e., PDB IDs: 2C1E and

1KMC29

). We will subsequently refer to the struc-

tures obtained at pH 4.5 and pH 7.4 as low-pH and

physiological-pH mature apo-caspase-6 structures,

respectively.

The caspase-6 protein used for crystallization at

physiological pH comprised residues 24–179 and

194–293 after self-cleavage of the expressed caspase-6

zymogen. Caspase activity was confirmed prior to

crystallization (Fig. 2). The electron density is well

defined for residues Phe31-Cys163 in the p20

subunit, residues Tyr198-Val212 and Thr222-

Arg260, and residues Gln274-Lys291 in the p10

subunit. Consequently, the first seven residues of

the N-terminus of the p20 subunit, as well as the last

two residues of the p10 subunit, were absent from

the electron density maps, and the loops constitut-

ing the catalytic grooves L2 (residues 163–179), L3

(212–222), and L4 (257–275) were found to be

disordered.

The L2′ loop

For inhibitor-bound caspase-3 and caspase-7, the

conformation of the loops forming the catalytic

groove has been shown to be stabilized by

interactions with the cleaved interdomain linker

loop L2′ of the adjacent p20/p10 dimer;30,31

however, in the structure of the pro-caspase-7

zymogen and the ligand-free caspase-7, the L2′

loop is folded back and located at the interface

between the two p10 subunits of the p202/p102

tetramer.32,33

In the apo-caspase-6 structure at

physiological pH, the L2′ loop is also oriented

towards the p10/p10′ interface (Fig. 3). It has

been proposed that the presence of inhibitor or

substrate triggers flipping of the L2′ loop.34

In

support of this hypothesis, apo-crystal structures

of caspase-3 and caspase-7 obtained in the

presence of inhibitor35,36

showed that the L2′

loop folded against the L2 and L4 loops. This was

in contrast to the zymogen-like conformation of

the L2′ loop in the previously reported apo-

caspase-7 structure crystallized in the absence of

inhibitor.33

These studies on caspase-3 and cas-

pase-7 suggest ligand-induced dynamics of the

L2′ loop. Our crystallography-based insight into

the mature apo-caspase-6 and literature evidence

further support the presence of multiple apostruc-

tures that are likely to result from the inherent

conformational freedom of the enzyme and could

be stabilized by ligand binding. In the apo-

caspase-6 crystals, the ligand binding site is

located at a large solvent channel through the

crystal and should be accessible to the ligand via

soaking. Furthermore, the conformation of the L4

loop is not restricted by crystal packing; thus,

rearrangement upon ligand binding should be

feasible. Based on this insight, we soaked an

inhibitor into the apo-caspase-6 crystals. Unfortu-

nately, this approach failed; specifically, longer

soaking times resulted in complete crystal decay,

whereas shorter exposure to the molecule afforded

low compound occupancy. We propose that

within the crystal packing context, the L2′ loop

in its locked position at the dimer interface is

not able to reorient towards, and to stabilize,

the L4 loop in a conformation required for

ligand binding, as observed in the Ac-VEID-CHO

caspase-6 complex. (Further details can be found

in Supplementary Material.)

Comparison with the Ac-VEID-CHO caspase-6

complex

In the Ac-VEID-CHO caspase-6 complex (PDB ID:

3OD523

), the L2′ loop is flipped by 180° and oriented

towards the L2/L4 loop interface of the neighboring

p20/p10 dimer (Fig. 3). The conformation of loops L2

and L3 closely resembles the one observed after the

Table 1. Data processing and refinement statistics

Parameter Apo-caspase-6

PDB ID 3P45

Space group P21

Cell dimensions

a, b, c (Å) 81.23, 161.24, 88.92

α, β, γ (°) 90.0, 94.80, 90.0

Resolution (Å) 30–2.53

Rmerge

a

(%) 10.1 (55.0)

Mean I/σIa

8.0 (2.0)

Completenessa

(%) 99.8 (99.8)

Multiplicity 2.9

Refinement

Number of reflections 75,784

Rwork/Rfree (%) 20.7/26.4

B-factors

Protein 10.3

Water 8.7

RMSD

Bond lengths (Å) 0.019

Bond angles (°) 1.742

a

Values in parentheses are for the highest-resolution shell.

309X-ray Structure of Active Caspase-6](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/e0c9e0d4-a6d3-4d52-aebb-e3a04c198c7d-150530213614-lva1-app6892/85/casp6-paper-JMB2011-3-320.jpg)

![In conclusion, this article describes the structures

of caspase-6 in its apo form at physiological pH. It

closely resembles mature ligand-free caspase-7 with

a central six-stranded mixed β-sheet flanked by five

α-helices. Loops L2, L3, and L4, which constitute the

ligand binding site in the Ac-VEID-CHO caspase-6

complex, are disordered, and the L2′ loop resides at

the p10/p10′ interface as observed in the caspase-6

zymogen structure. Our results indicate that the

presence of ligand induces loop L2′ to reorient

towards, and to stabilize, the L2 and L4 loops of the

neighboring p20/p10 dimer, with the L2′ flip

required for ligand binding. The overall topology

of the apostructure at physiological pH is distinct

from the structural data previously reported for

caspase-6 at pH 4.5. Even though its noncanonical

fold does not impair inhibitor binding, we think that

it does not represent a physiologically relevant

conformation that would provide an allosteric site

for drug development.

Materials and Methods

Gene construction and protein expression

Oligonucleotides were designed to amplify the cata-

lytic domain (amino acid residues 24–293) of human

caspase-6 for cloning into a BioFocus in-house expres-

sion vector. cDNA products of the correct size for

caspase-6 were obtained from polymerase chain reaction

experiments using cDNA encoding full-length caspase-6.

Products were successfully cloned into the BioFocus

vector pT7-CH for Escherichia coli expression under the

control of the T7 promoter. The vector–insert combina-

tion provided a C-terminal hexa-histidine purification

tag on the expressed protein. For large-scale expression,

recombinant human caspase-6 was expressed in Rosetta

E. coli cells grown overnight at 37 °C from glycerol

stock. The next day, 6×1 L cultures were inoculated

with 50 ml of overnight starter cultures. Cells were

grown at 37 °C until an OD600 of 1.2 had been reached.

Cells were cooled to 25 °C, induced with 0.5 mM IPTG,

and shaken overnight before being harvested. Cell

pellets were harvested, washed with phosphate-buffered

saline, and then stored at −80 °C. We found that the

temperature had clearly an effect on the yield of fully

processed caspase-6 protein, as induction at 25 °C,

compared to 37 °C, resulted in higher yields. In addition,

increased protein yields were also obtained when the

cells were induced at a higher cell density.

Protein purification

Cell paste from 6×1 L cultures was resuspended on ice

in 100 ml of 25 mM Tris (pH 8.0) containing 25 mM

imidazole, 100 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, and 0.1% 3-[(3-

cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]propanesulfonic

acid. Following mechanical disruption of the cells, the

soluble fraction was harvested by centrifugation at

60,000g for 30 min. The cleared supernatant was incubated

batchwise with 0.5 ml of NiNTA (Qiagen) for 2 h at 4 °C to

allow binding. The resin was collected by centrifugation at

400g and washed once with buffer A [25 mM Tris (pH 8.0)

containing 25 mM imidazole, 100 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol,

and 0.1% 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]pro-

panesulfonic acid] before being loaded into an Omnifit

column. The column was attached to an ÄKTAexpress,

run through IMAC elution (using buffer A supplemented

with 500 mM imidazole and 10 mM DTT), and then

subjected to size-exclusion chromatography [with a

Superdex 200 16/60 column equilibrated in 20 mM

sodium acetate (pH 5.5) containing 50 mM NaCl and

10 mM DTT], as the protein was most stable for storage

under these conditions. After size-exclusion chromatog-

raphy, the fractions were collected and analyzed by SDS-

PAGE stained with Coomassie brilliant blue. The purest

fractions were pooled, concentrated to 8.2 mg/ml by

ultrafiltration, and used for crystallization. DTT (10 mM)

was added to the concentrated protein prior to crystalli-

zation. Protein concentration was determined with

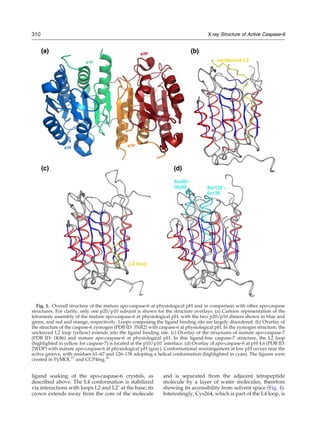

Fig. 4. Comparison of inhibitor-bound caspase-3, caspase-6, and caspase-7 structures. Interaction of the L4 loop

residues with the P4 site of bound peptide in the Ac-VEID-CHO caspase-6 (PDB ID: 3OD5; gray), Ac-DEVD-CHO

caspase-3 (PDB ID: 2H5I; magenta), and Ac-DEVD-CHO caspase-7 (PDB ID: 1F1J; blue) complexes, respectively. In

contrast to the caspase-3 and caspase-7 complexes, all hydrogen bonds between the L4 loop and the inhibitor peptide are

water mediated in the caspase-6 complex. The figures were created in PyMOL.27

312 X-ray Structure of Active Caspase-6](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/e0c9e0d4-a6d3-4d52-aebb-e3a04c198c7d-150530213614-lva1-app6892/85/casp6-paper-JMB2011-6-320.jpg)

![Coomassie Plus reagent, measuring optical absorbance at

595 nm.

Protein activity

Caspase-6 activity was confirmed using an assay that is

based on the protolytic cleavage of a fluorogenic substrate.

This substrate consists of two caspase-6 recognition

peptide molecules that are covalently linked to two

amine groups of the fluorescent dye rhodamine 110

(Z-VEID-R110; Invitrogen), which suppresses R110 fluo-

rescence. During proteolysis, both recognition peptides

are cleaved off, and subsequent dequenching of the dye

indicates enzymatic activity. Pipes (20 mM; pH 7.4),

100 mM NaCl, 0.03% Pluronic®, 10% sucrose, 1 mM

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, and 5 mM glutathione

were used as assay buffer. The enzyme concentration was

determined with Coomassie Plus reagent, measuring

optical absorbance at 595 nm. Recombinant caspase-6

activity was detected by measuring the R110 release from

Z-VEID-R110 at 37 °C using a Perkin-Elmer EnVision® at

an excitation wavelength of 485±14 nm and at an

emission wavelength of 535±25 nm. The enzyme prepa-

ration used in the enzymatic studies was titrated using the

substrate Z-VEID-R110 and was found to be active (results

not shown). The inhibitor concentration that results in 50%

inhibition (IC50) was determined for the reported caspase-

6-competitive and caspase-6-reversible inhibitor Ac-VEID-

CHO.39,40

The inhibitor was resuspended in dimethyl

sulfoxide, serially diluted in assay buffer, and combined

with 1 pg of caspase-6 on a 96-well plate. The maximum

dimethyl sulfoxide concentration was 1%, and the

caspase-6 substrate was used at a concentration of 10 μM.

Crystallization and data collection

Crystals of mature apo-caspase-6 were obtained with

hanging-drop vapor diffusion on 24-well plates (VDXm;

Hampton Research) at 20 °C by mixing 1.0 μl of protein

solution [in 20 mM sodium acetate (pH 5.5), 50 mM NaCl,

and 0.5 mM Tris(hydroxypropyl)phosphine] with 1.0 μl of

reservoir solution (0.5 ml) consisting of 3.3 M sodium

nitrate, 0.1 M Tris (pH 7.4), 0.5% ethyl acetate, and 5 mM

Tris(hydroxypropyl)phosphine. Single crystals

(0.5 mm×0.3 mm×0.1 mm) grew by microseeding

straight into the drop after setup within 1 week at 20 °C.

The crystallization drop was overlaid with 3 μl of

cryoprotectant containing 20% ethylene glycol, 3.5 M

sodium nitrate, and 0.1 M Tris–HCl (pH 7.4), and a crystal

was harvested for data collection. The crystal was flash

frozen in liquid nitrogen, and X-ray data collection was

carried out at 100 K on a Rigaku R-Axis IV image plate

detector, with data indexed, integrated, and scaled using

MOSFLM and SCALA (CCP4),41–43

respectively.

Structure solution and refinement

Chain A of the pH-inactivated caspase-6 model com-

prising residues 31–293, representing one p20/p10 dimer,

was used for molecular replacement using Phaser,44

locating eight p20/p10 subunits in the asymmetric unit.

The resulting model was given two rounds of atomic

refinement with tight geometric weights using

REFMAC5.45

The electron density maps calculated after

molecular replacement and initial refinement were exam-

ined, and residues with a poor fit to the electron density

map were omitted from the model. The truncated model

was used as a starting model for automated model

building in Buccaneer.46

Possibly due to the disorder of

a large number of surface loops and hence chain breaks

around the active site, automated model building failed to

improve the initial model. In an alternative approach,

NCS-averaged electron density maps were calculated in

PARROT47 and used to rebuild missing residues manually

in Coot.48

The resulting extended model was then refined

using REFMAC5. To account for differences in thermal

motion, we performed TLS refinement on the completed

model, with one TLS group per p10/p20 heterodimer.

Water molecules were then added using the water

placement option in Coot and refined using REFMAC5.

For all eight heterodimer molecules in the asymmetric

unit, chain breaks are observed between ~Ala162 and

Tyr198, between ~Val212 and Thr222, and between

~Arg260 and Gln274, and the residues were omitted

from the model. Structural geometry was checked using

PROCHECK and MolProbity.49,50

Accession number

Atomic coordinates and structure factors have been

deposited in the PDB under accession code 3P45.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data associated with this article

can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/

j.jmb.2011.05.020

References

1. Li, J. & Yuan, J. (2008). Caspases in apoptosis and

beyond. Caspases in apoptosis and non-apoptotic

processes. Oncogene, 27, 6194–6206.

2. Lavrik, I. N., Golks, A. & Krammer, P. H. (2005).

Caspases: pharmacological manipulation of cell death.

J. Clin. Invest. 115, 2665–2672.

3. Mykles, D. L. (2001). Proteinase families and their

inhibitors. Methods Cell Biol. 66, 247–287.

4. Earnshaw, W. C., Martins, L. M. & Kaufmann, S. H.

(1999). Mammalian caspases: structure, activation,

substrates, and functions during apoptosis. Annu.

Rev. Biochem. 68, 383–424.

5. Thornberry, N. A. & Lazebnik, Y. (1998). Caspases:

enemies within. Science, 281, 1312–1316.

6. de Calignon, A., Fox, L. M., Pitstick, R., Carlson, G. A.,

Bacskai, B. J., Spires-Jones, T. L. & Hyman, B. T. (2010).

Caspase activation precedes and leads to tangles.

Nature, 464, 1201–1204.

7. Guo, H., Albrecht, S., Bourdeau, M., Petzke, T.,

Bergeron, C. & LeBlanc, A. C. (2004). Active caspase-6

and caspase-6-cleaved tau in neuropil threads, neuritic

plaques, and neurofibrillary tangles of Alzheimer's

disease. Am. J. Pathol. 165, 523–531.

313X-ray Structure of Active Caspase-6](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/e0c9e0d4-a6d3-4d52-aebb-e3a04c198c7d-150530213614-lva1-app6892/85/casp6-paper-JMB2011-7-320.jpg)