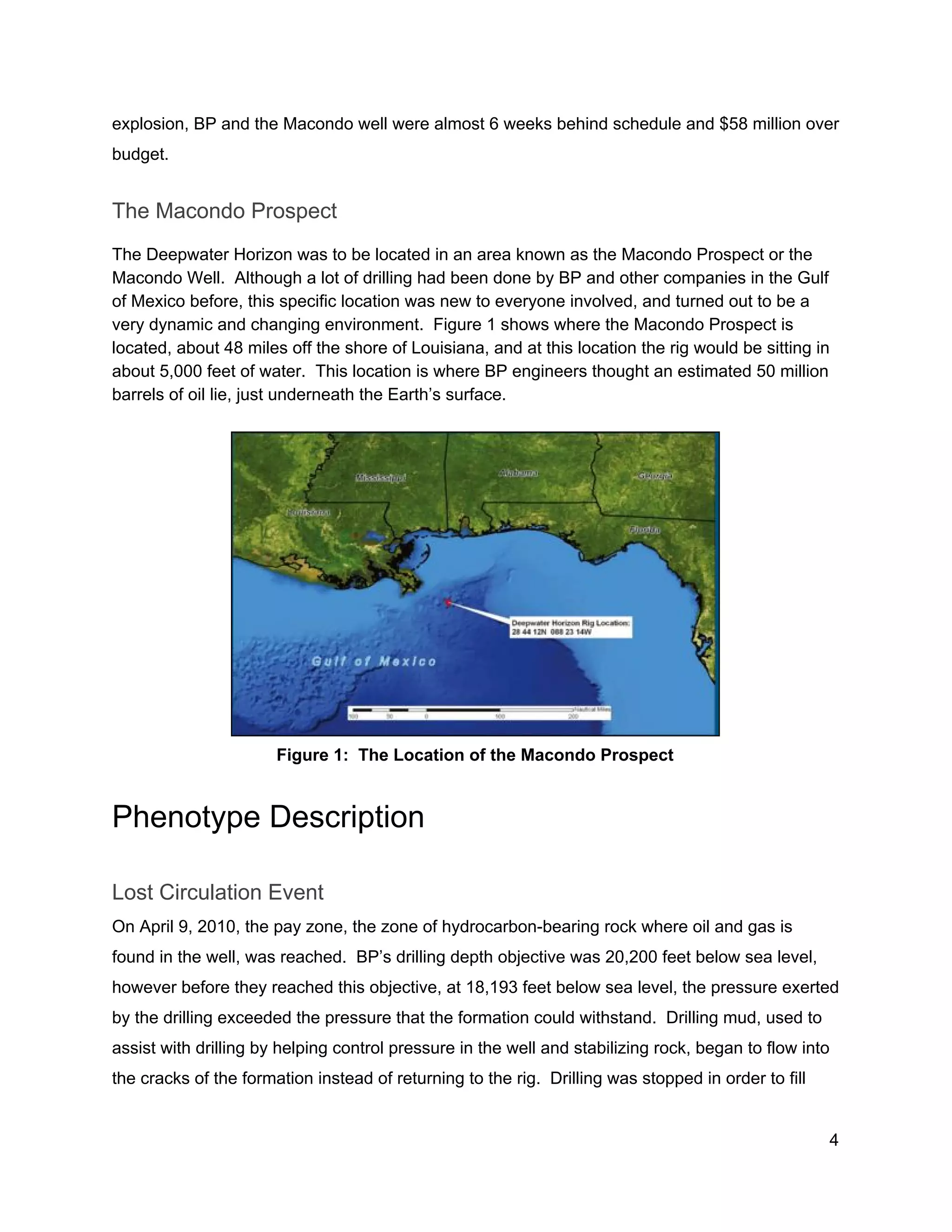

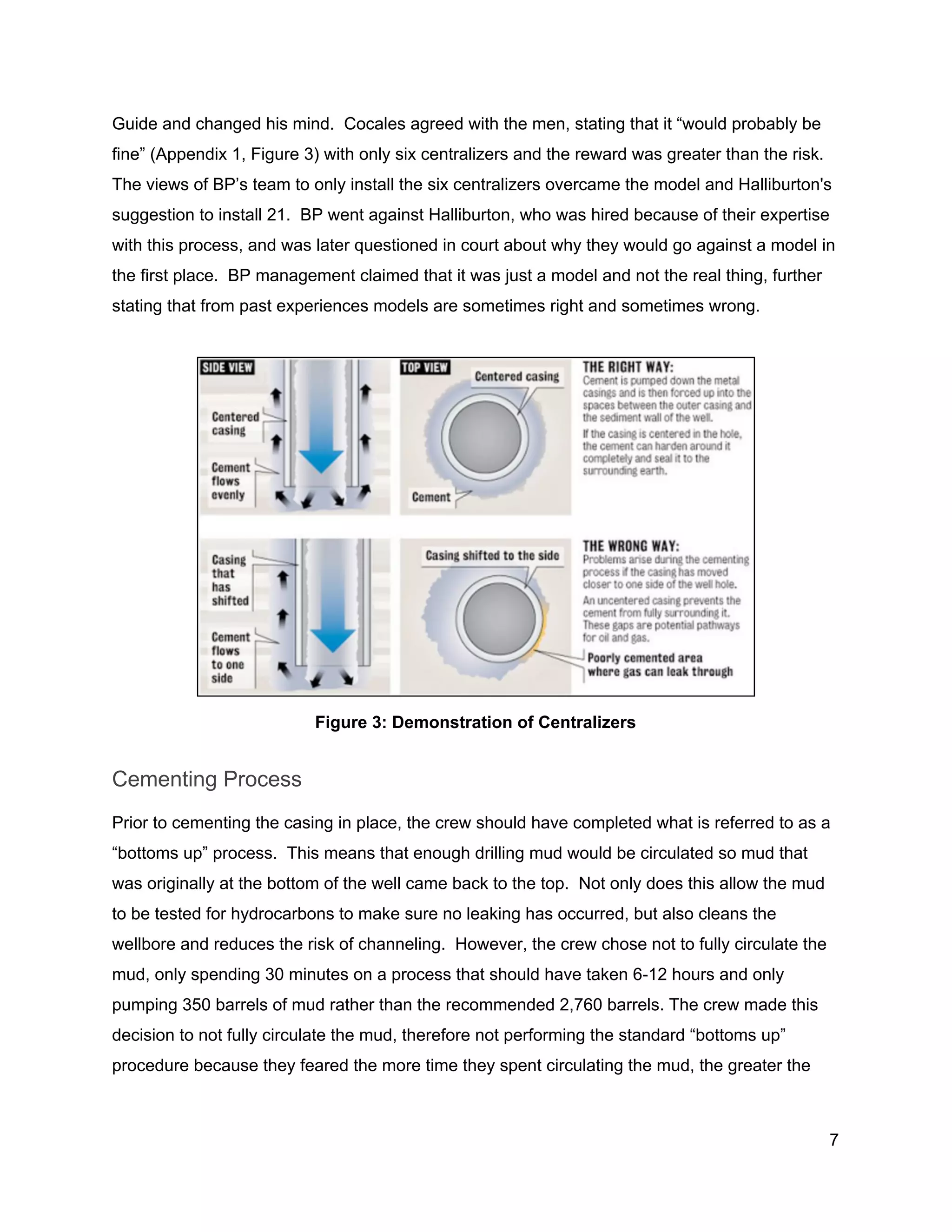

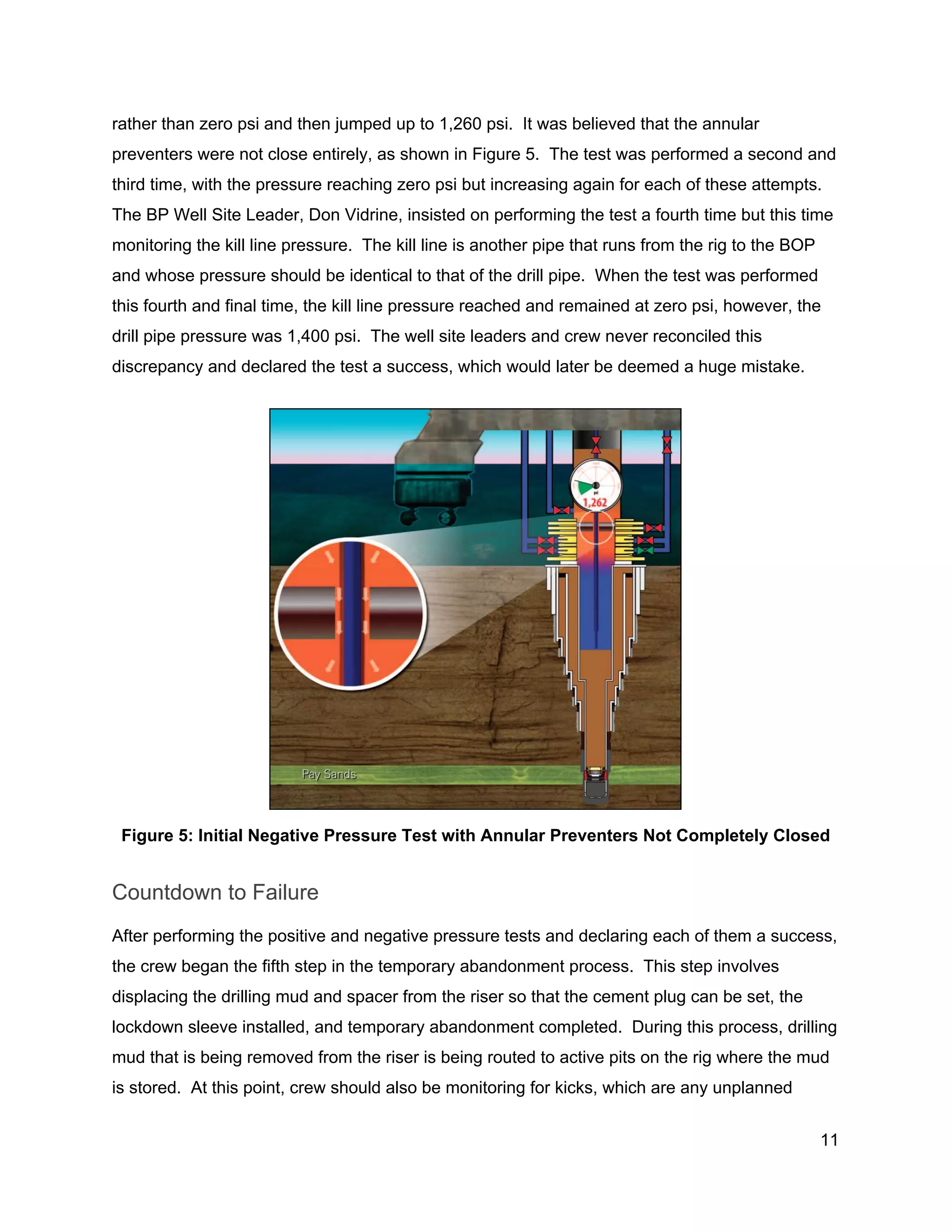

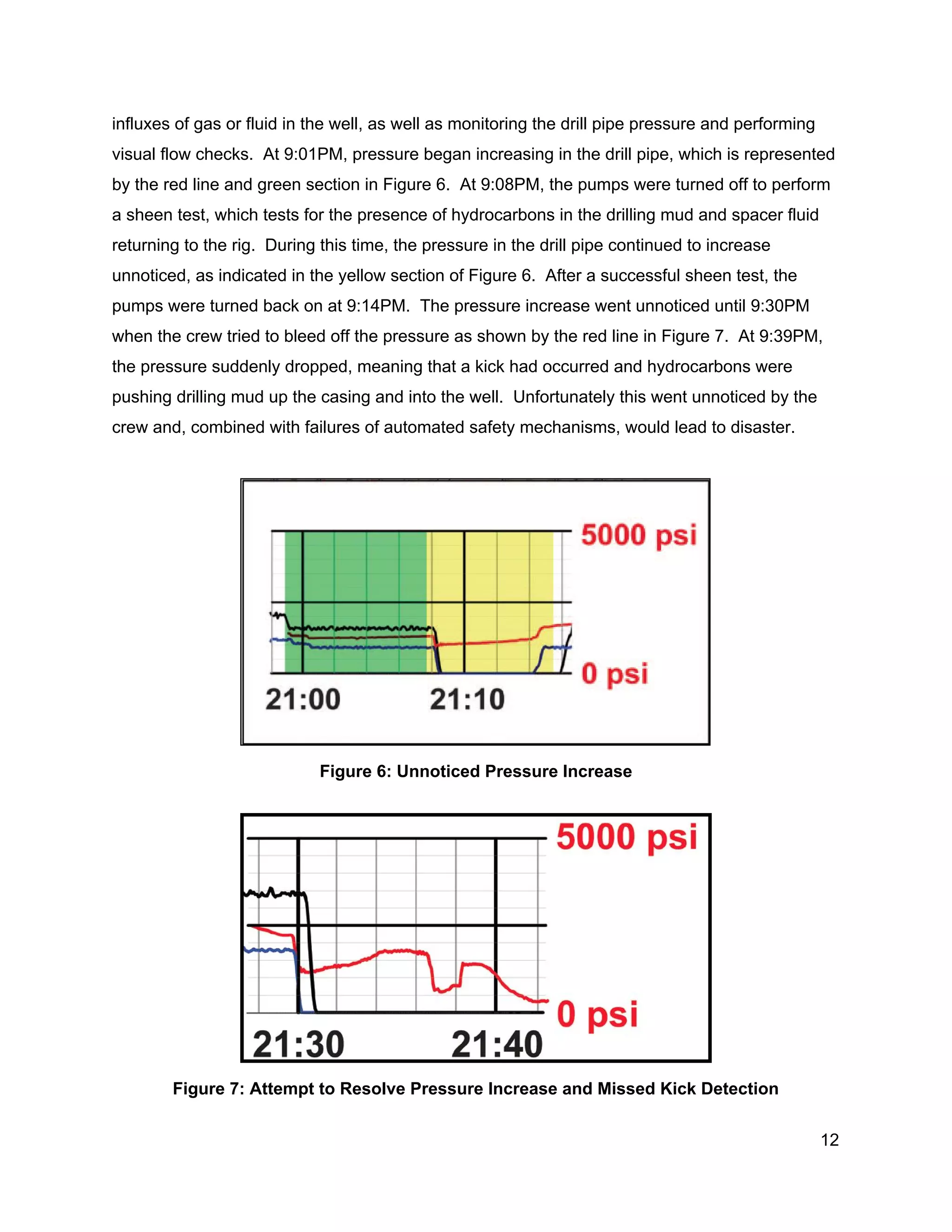

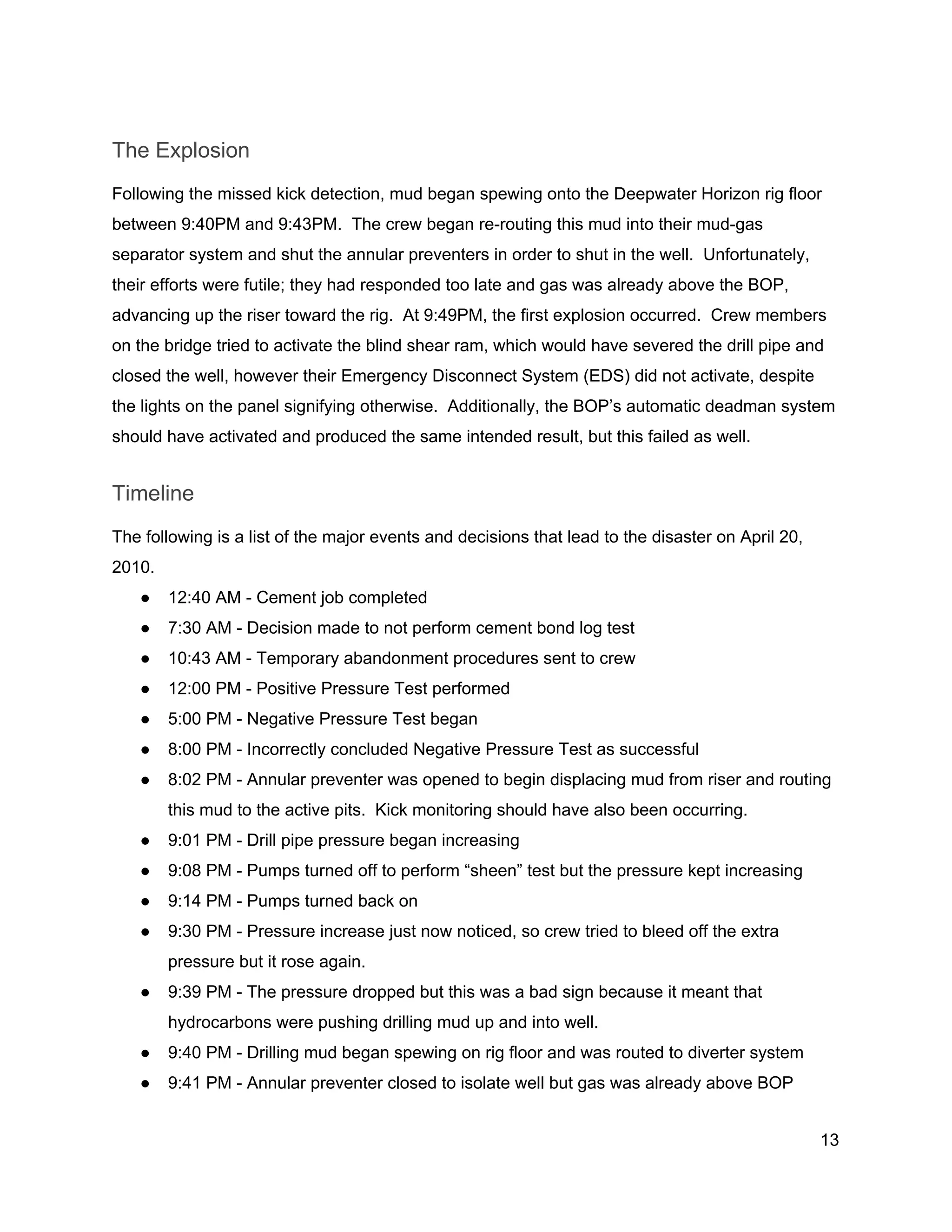

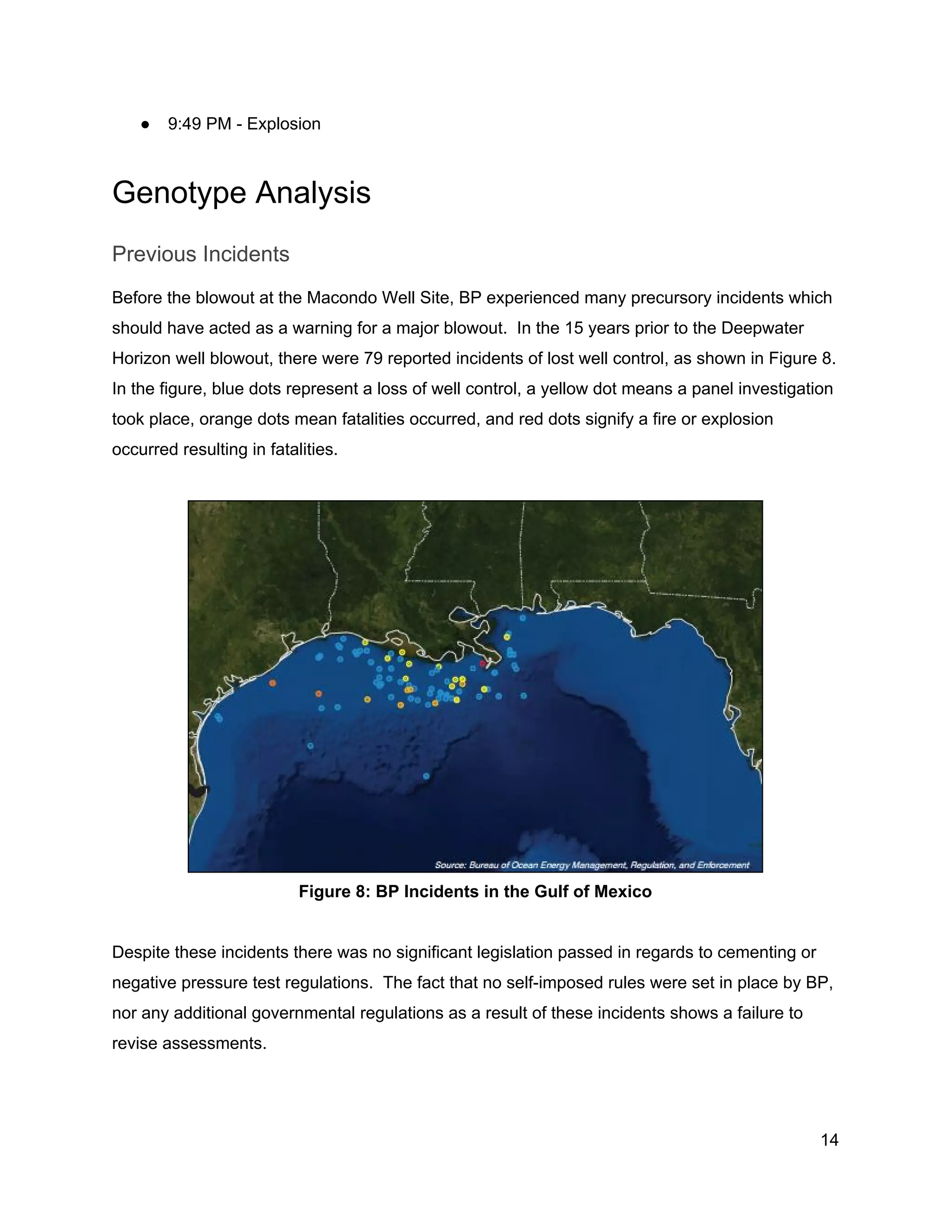

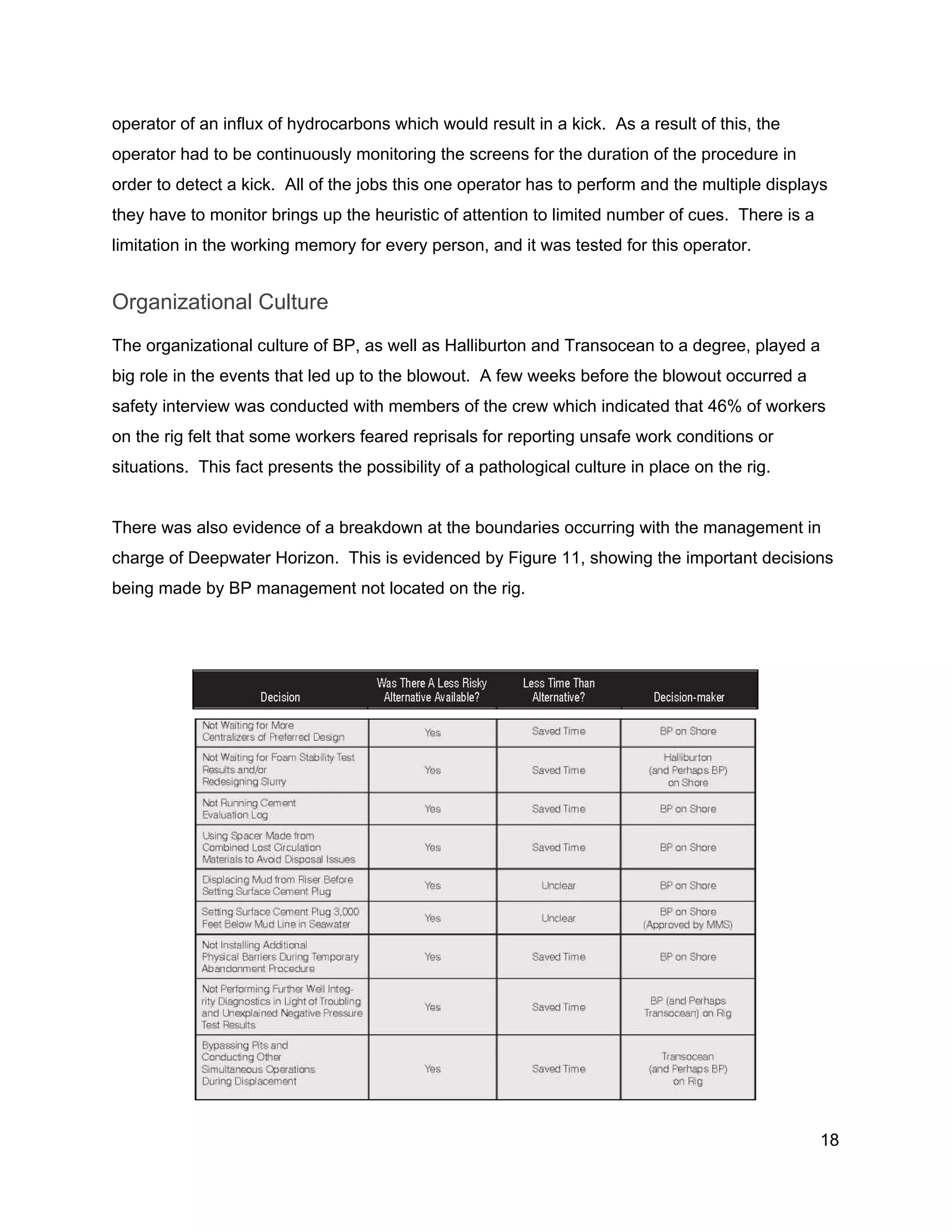

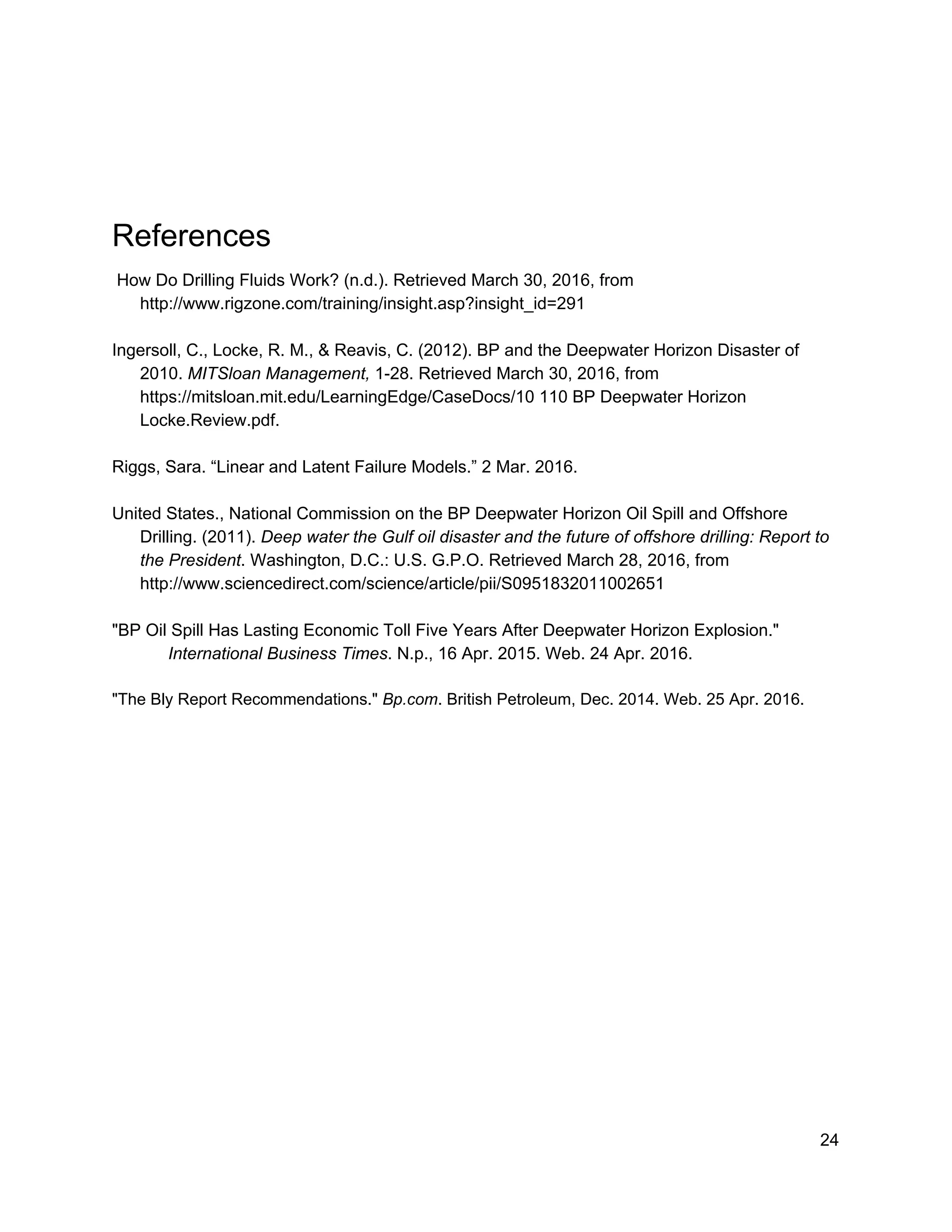

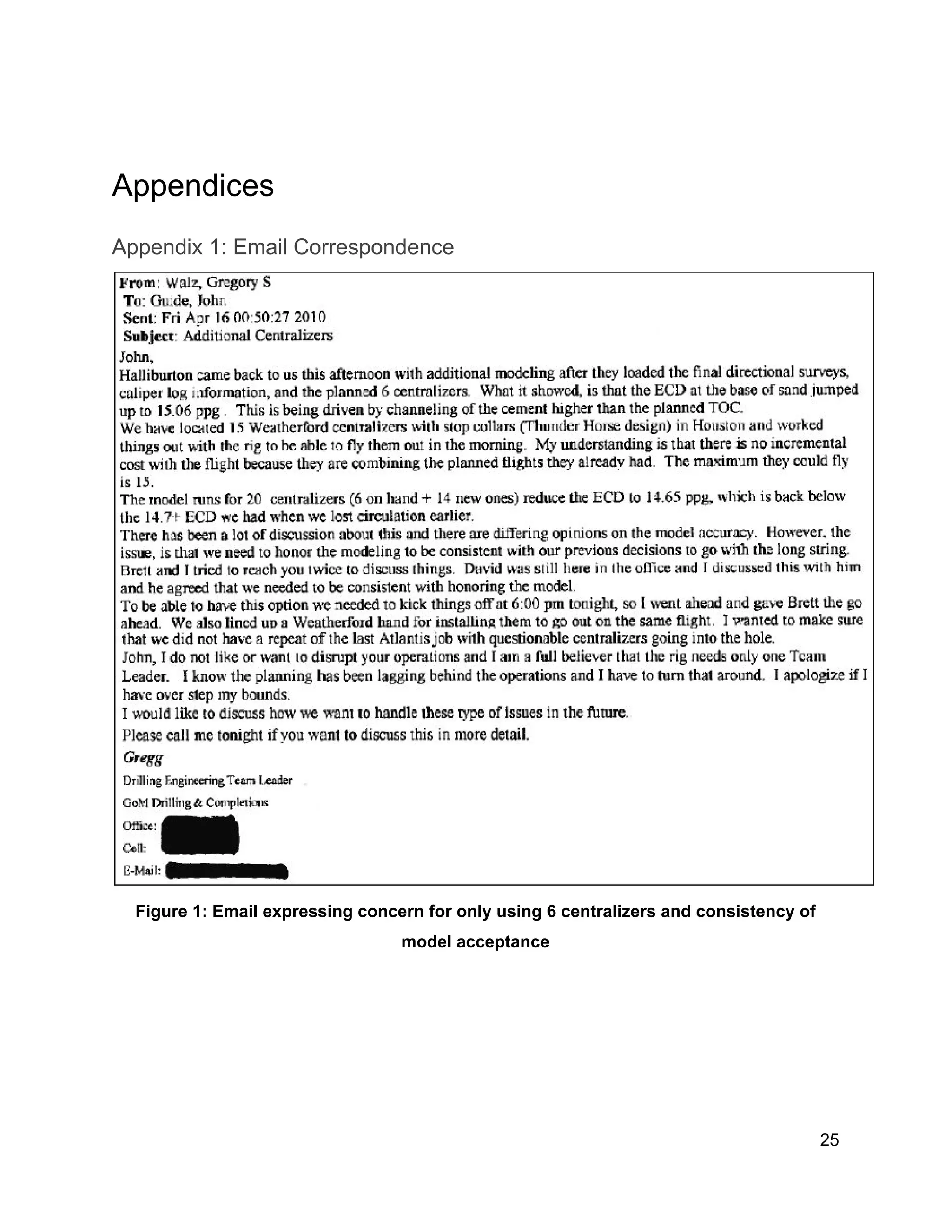

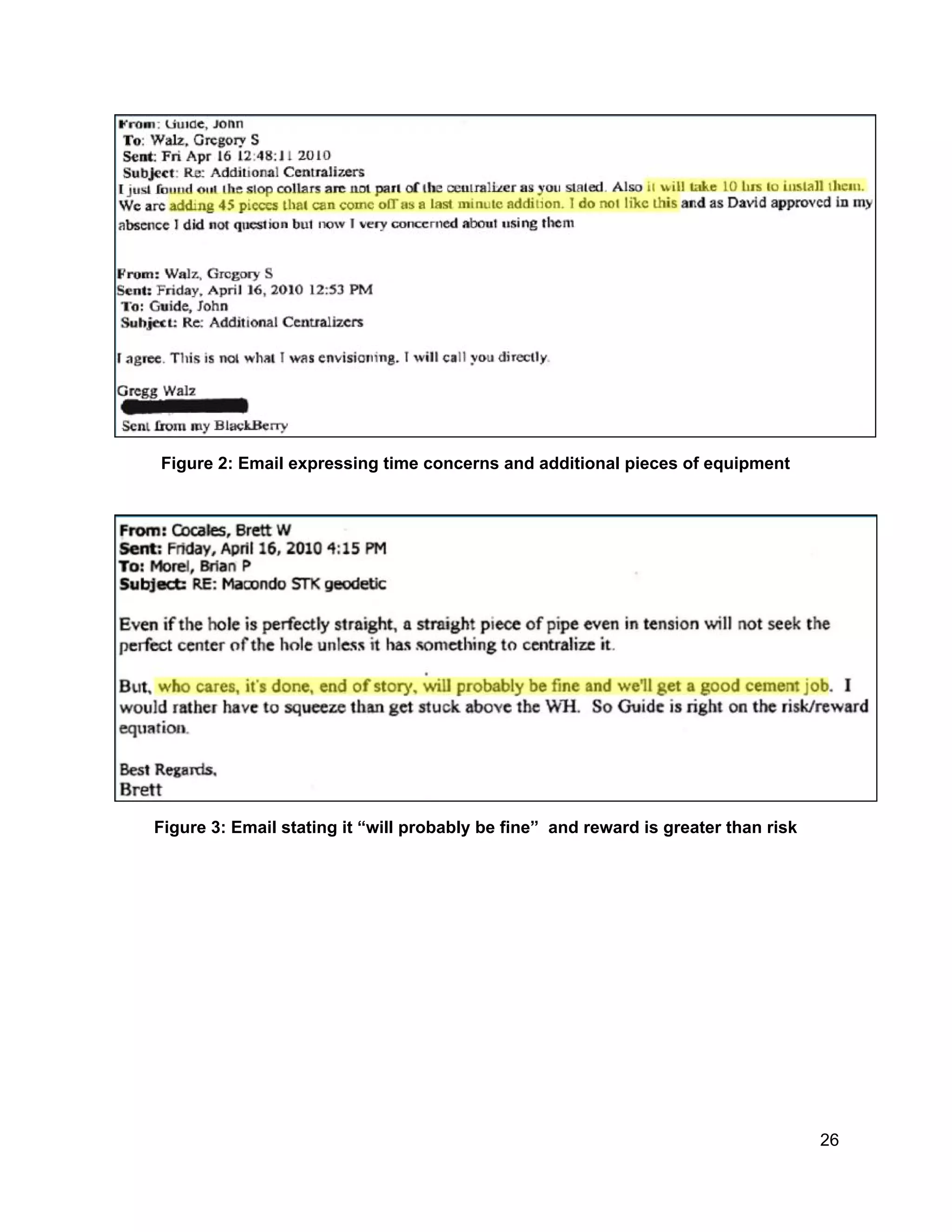

The document summarizes the Deepwater Horizon oil spill disaster that occurred in 2010. It describes how the Deepwater Horizon oil rig was drilling the Macondo well in the Gulf of Mexico when an explosion killed 11 crew members and led to the largest marine oil spill in history. The summary identifies several key failures that contributed to the disaster, including a lost circulation event during drilling, the decision to use a long string casing instead of a liner, installing only 6 centralizers instead of the recommended 21, and not fully circulating drilling mud prior to the cementing process. The document concludes by discussing the aftermath of the spill and recommendations to prevent future disasters.