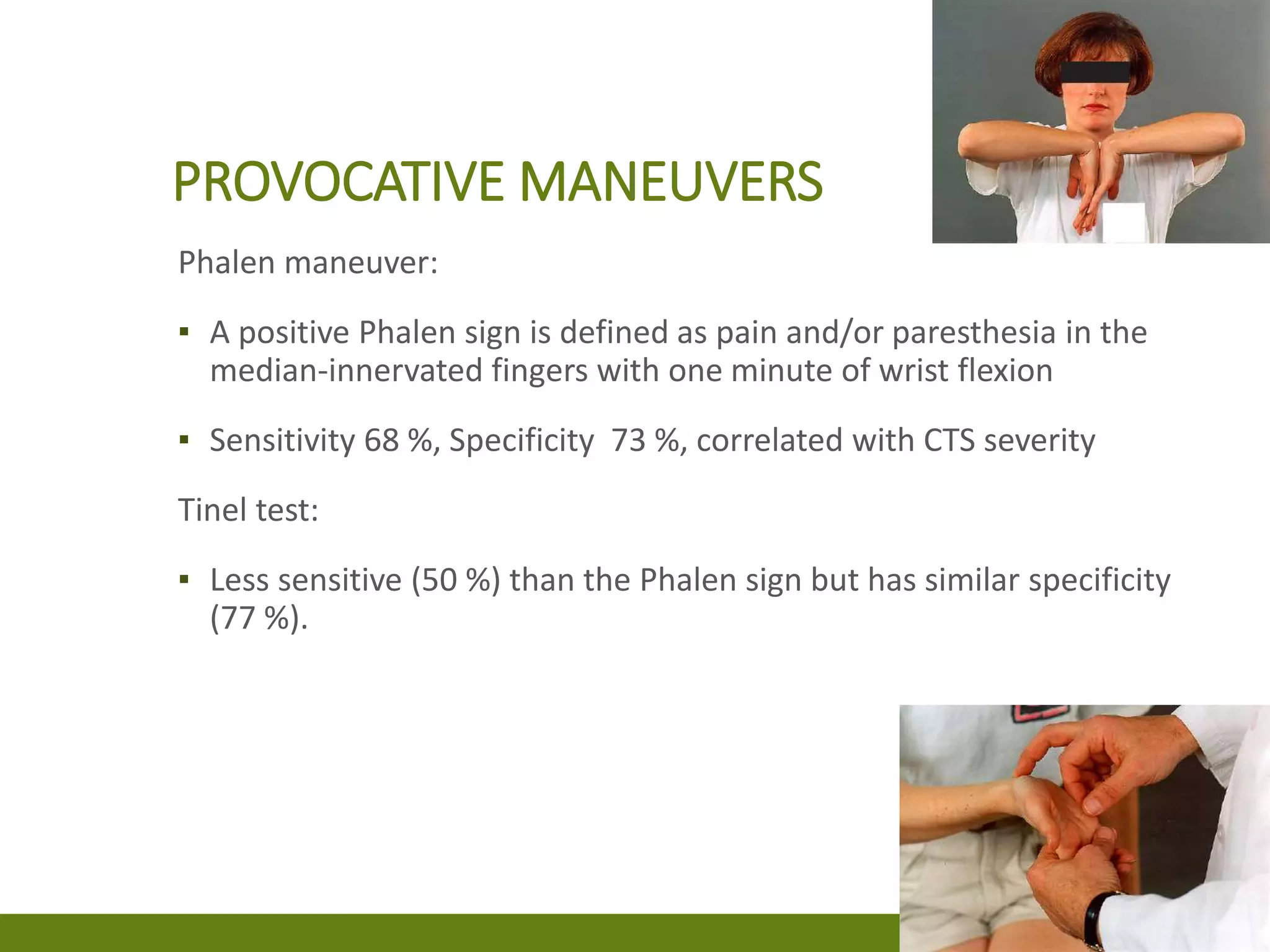

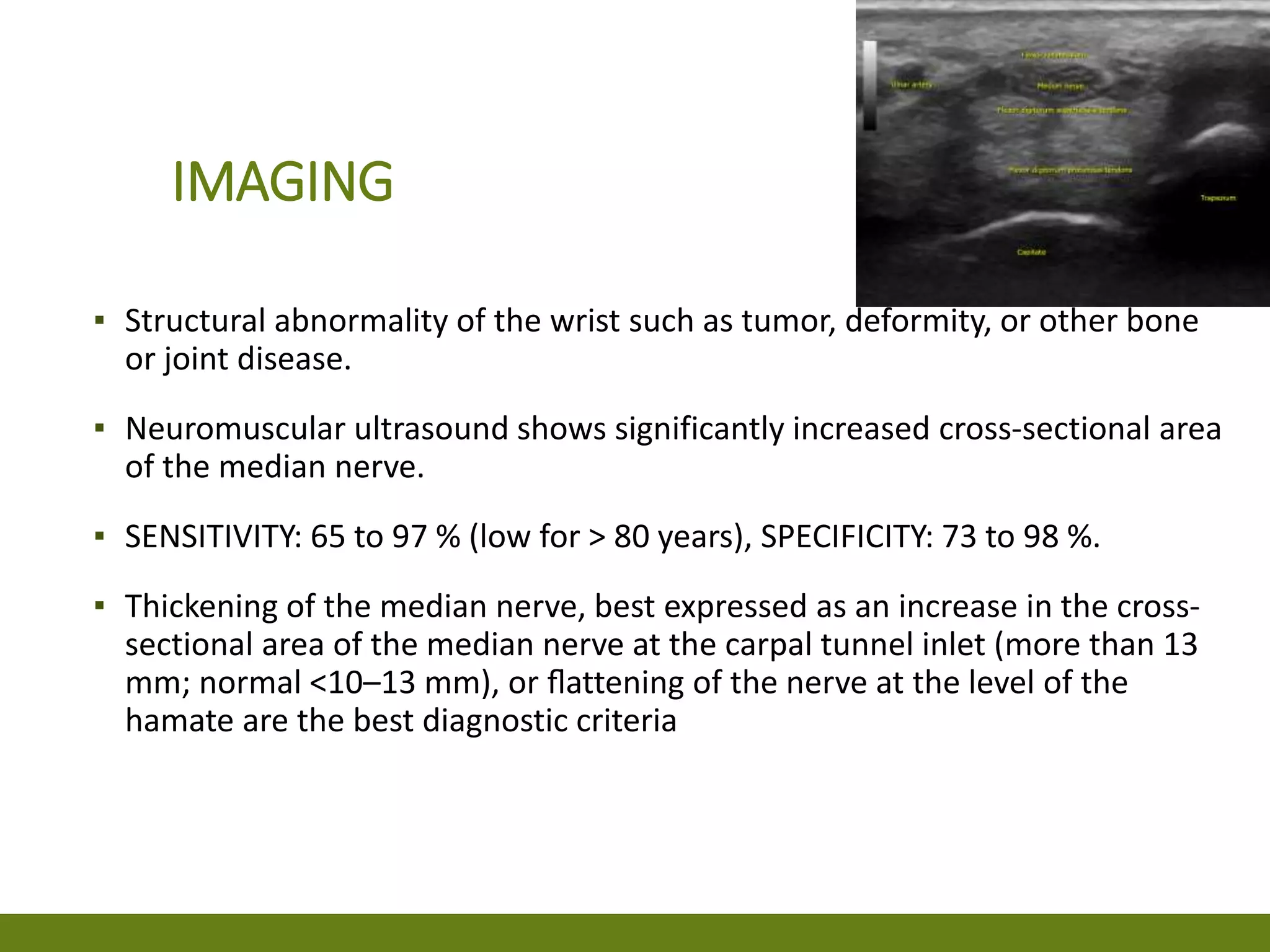

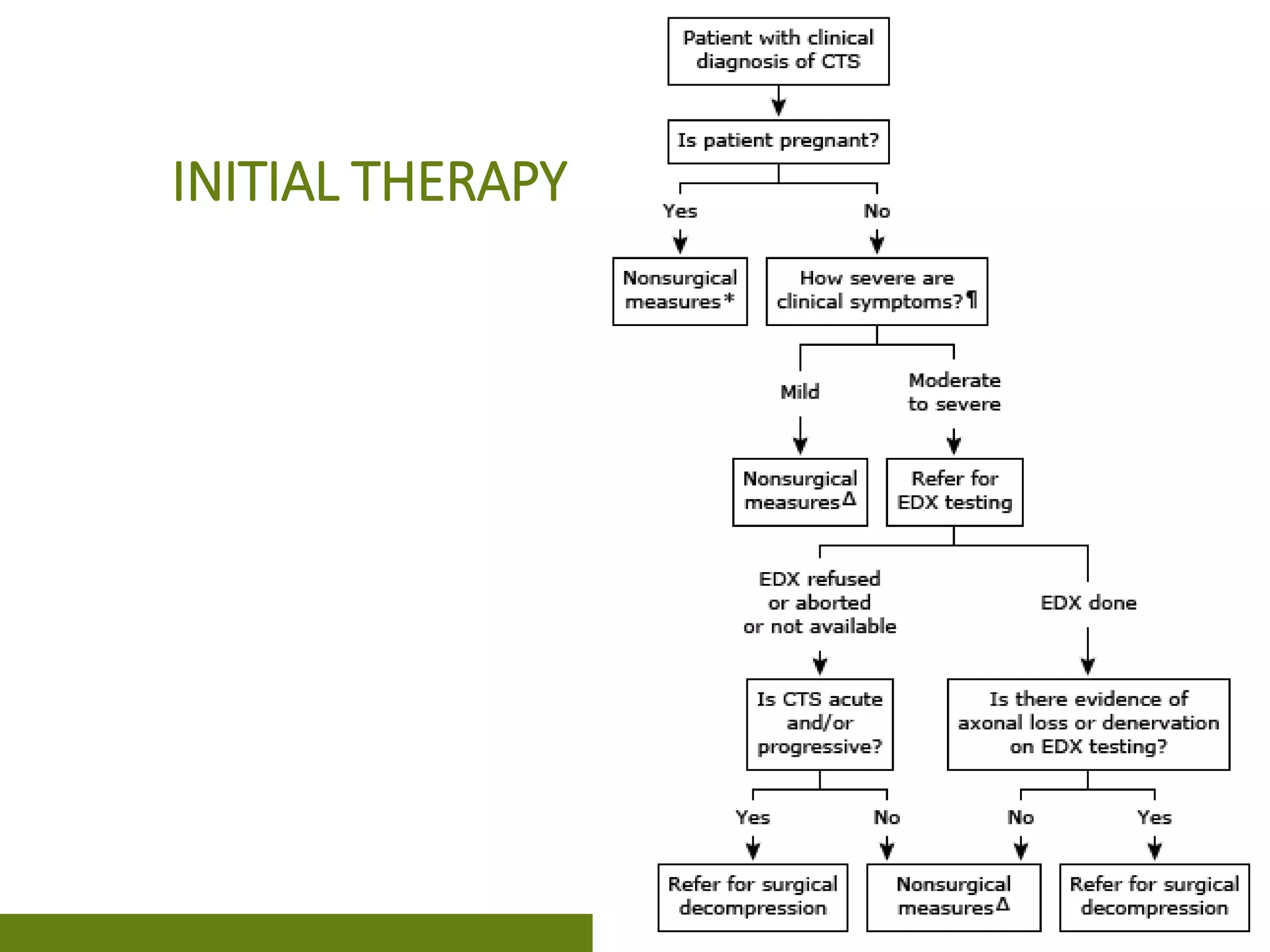

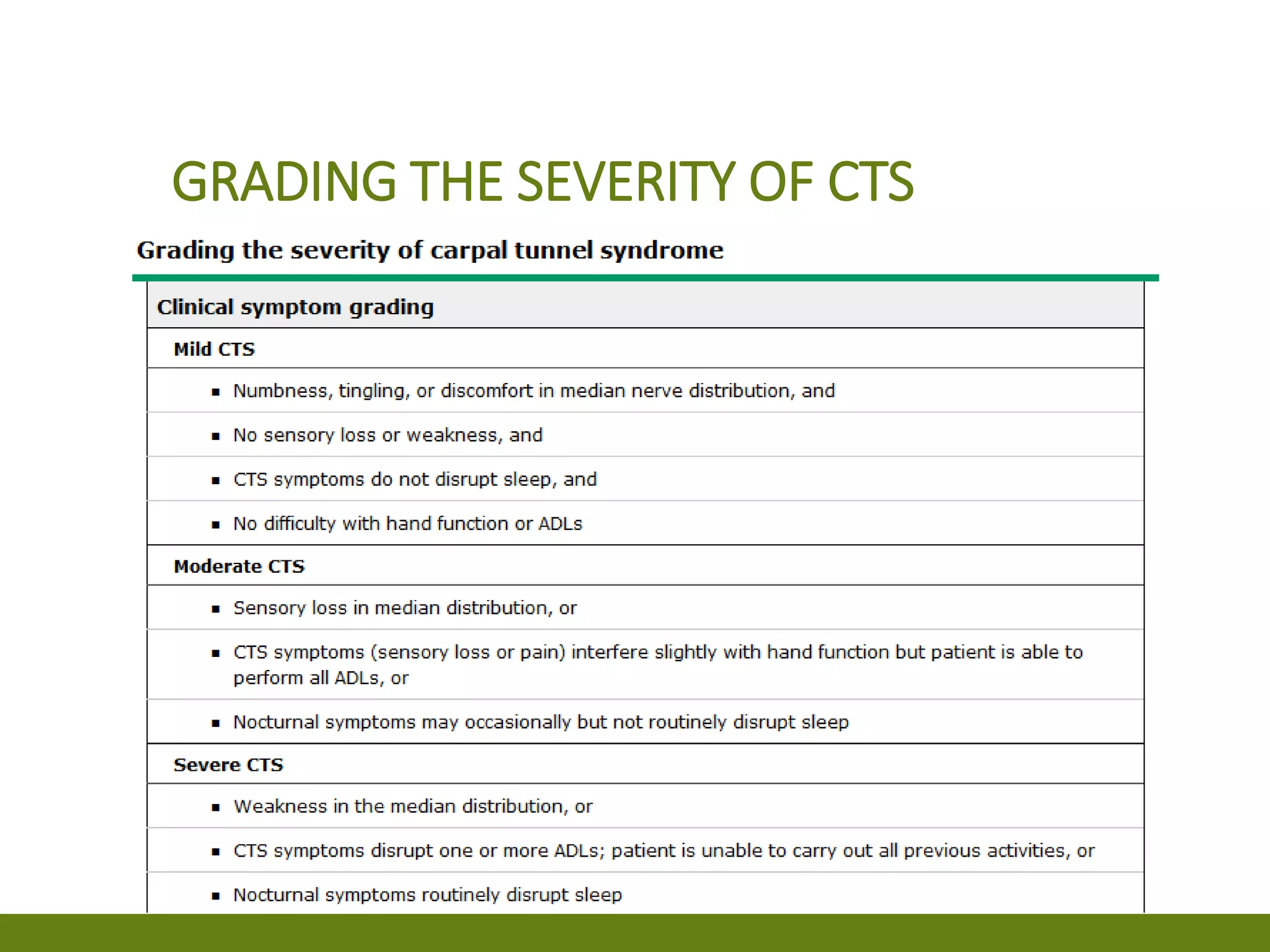

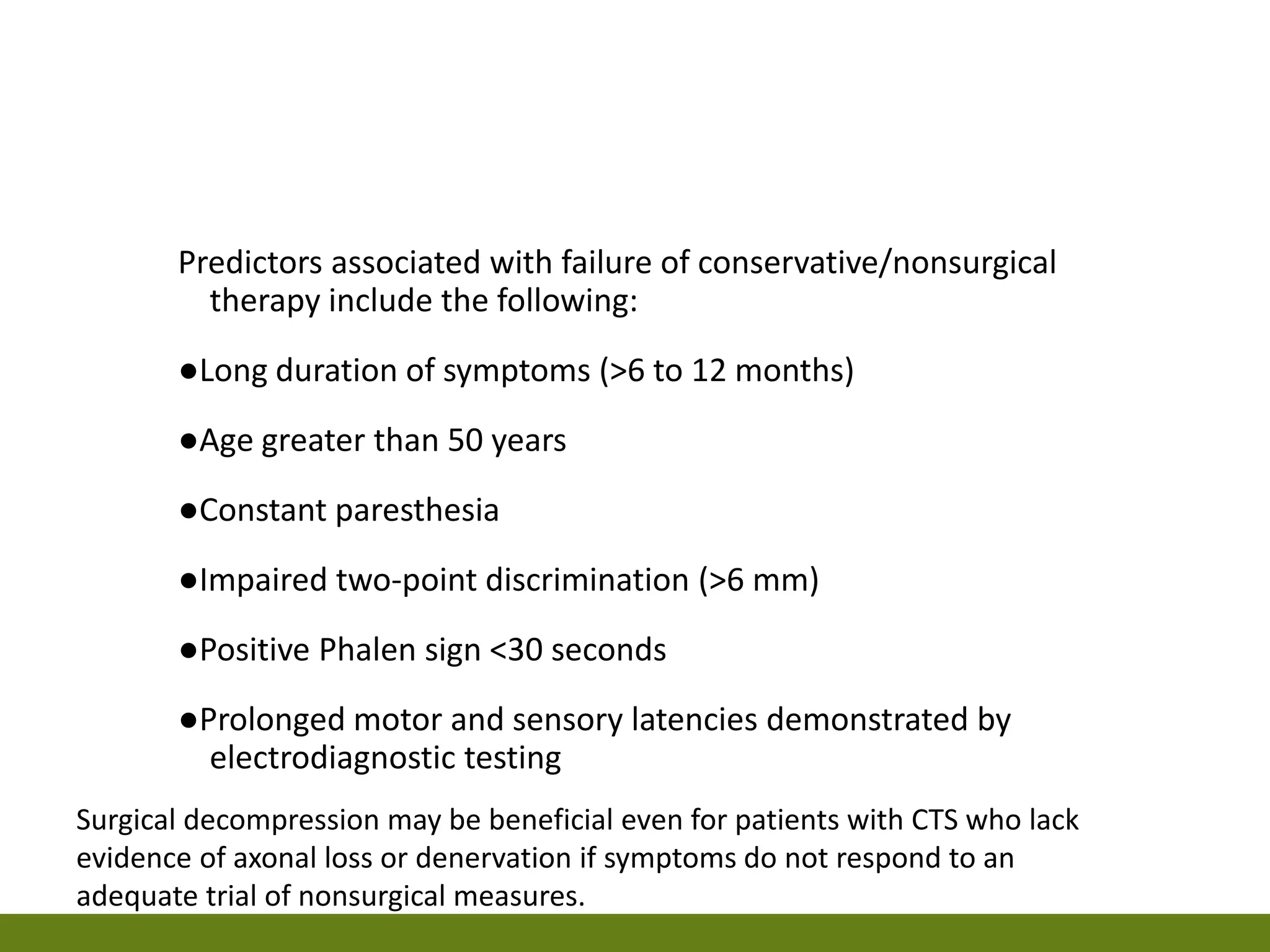

Carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) is caused by compression of the median nerve as it passes through the carpal tunnel of the wrist. Patients experience pain, numbness, and tingling in the hand that is worsened by activities like driving or typing. The diagnosis is made clinically based on symptoms and physical exam maneuvers like the Phalen's test. Electrodiagnostic studies are used to confirm CTS and assess severity through measuring median nerve conduction across the carpal tunnel. Surgical release of the transverse carpal ligament is considered for moderate to severe cases unresponsive to more conservative treatments.