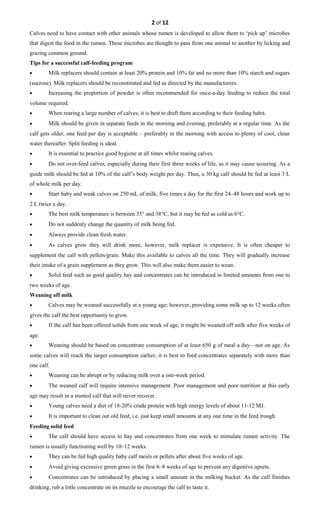

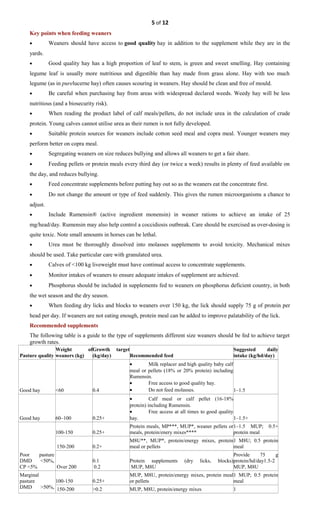

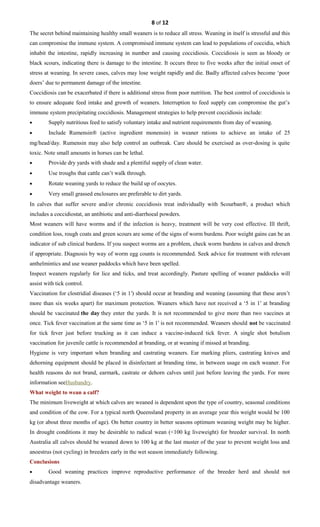

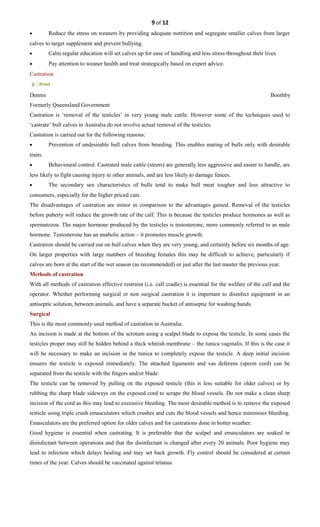

Rearing calves requires commitment to keeping them in a clean, comfortable environment with adequate feeding and protection from sickness. Newborn calves must receive colostrum within 36 hours to gain immunity. Orphan calves may show signs of dehydration or lack of appetite and require electrolyte solutions before milk feeding. Calves can be bottle or bucket fed but bucket feeding may cause scouring if the reflex to close the esophageal groove is not triggered. Weaning involves gradually reducing milk while increasing solid feed intake over one week to prevent stress or stunted growth. Yard training of weaners at weaning helps socialize them and makes them easier to handle throughout life.