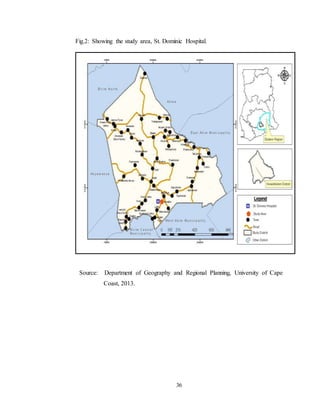

This document provides background information on a study exploring the implementation challenges of Ghana's Free Maternal Health Care policy at the St. Dominic Hospital in Akwatia. The policy was introduced to improve maternal health and reduce mortality. However, the hospital has seen a decline in supervised deliveries and an increase in maternal deaths among women aged 25-29. The study aims to identify policy-related, external, and internal factors challenging the policy's implementation and make recommendations to address these challenges.