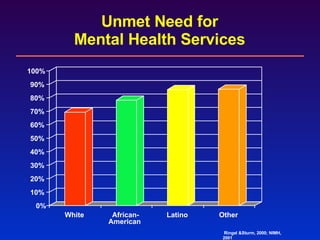

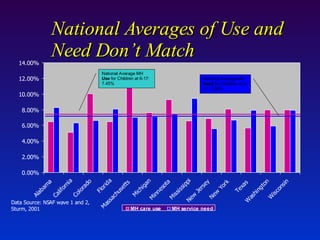

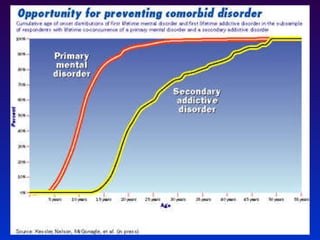

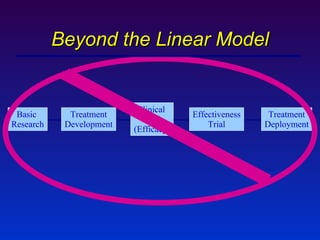

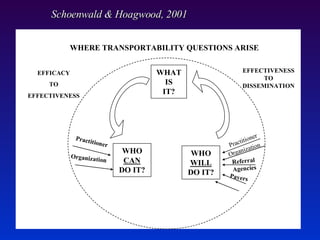

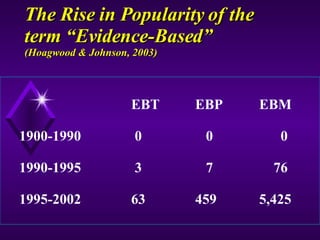

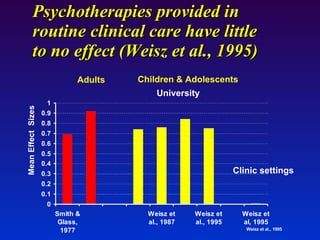

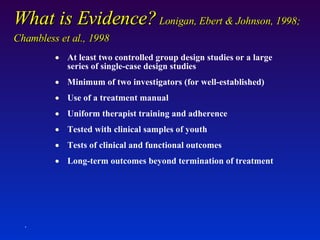

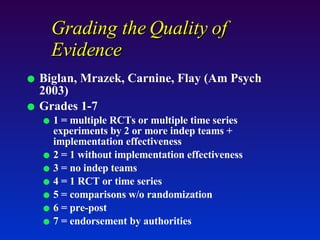

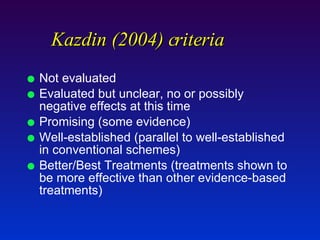

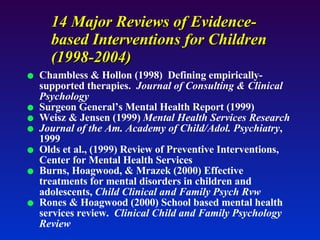

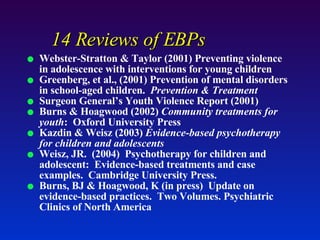

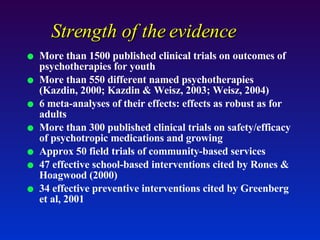

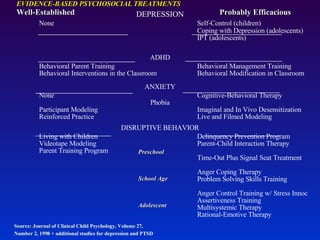

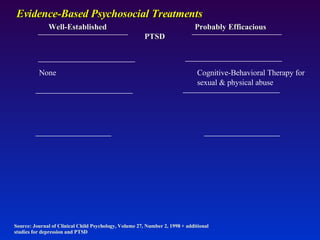

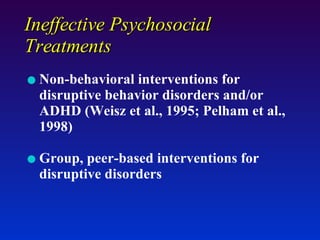

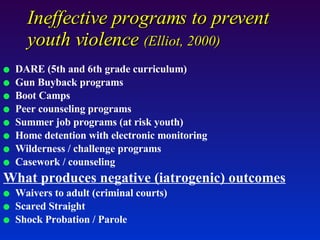

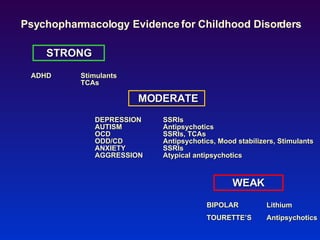

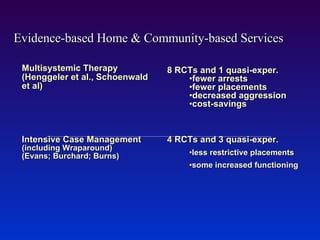

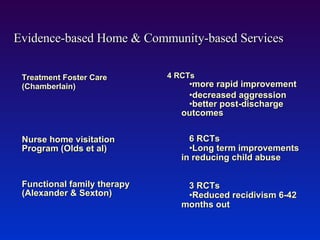

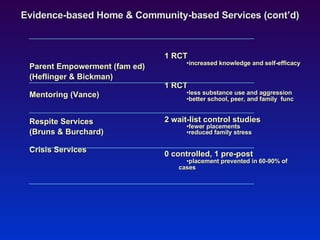

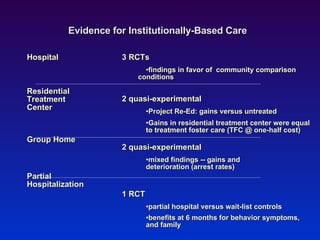

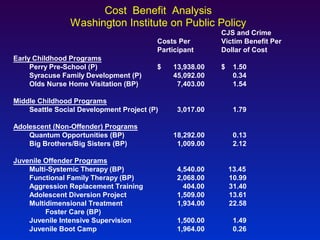

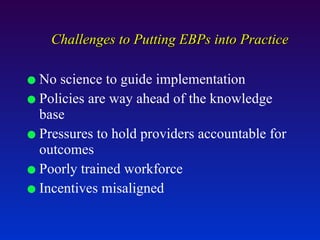

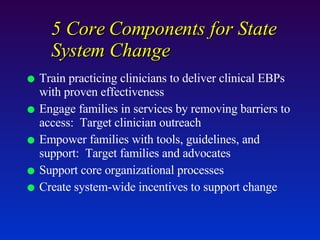

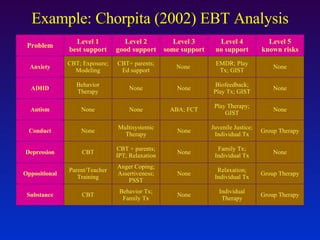

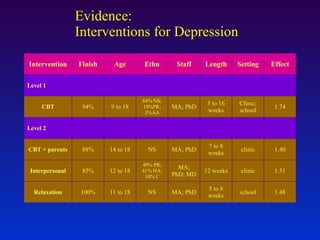

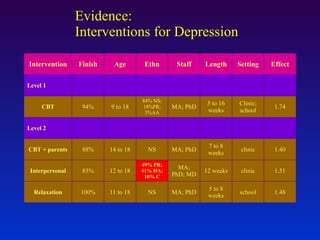

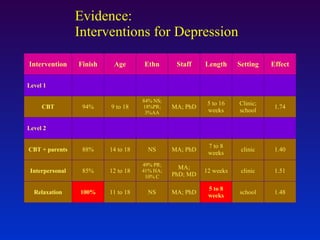

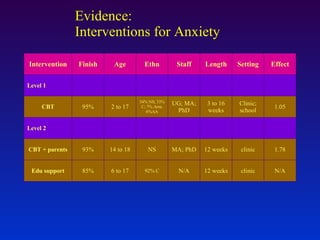

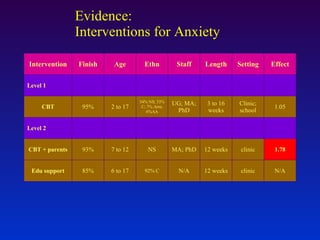

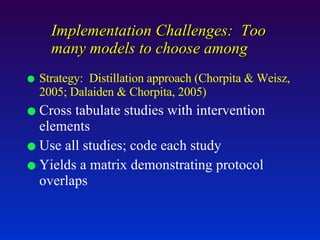

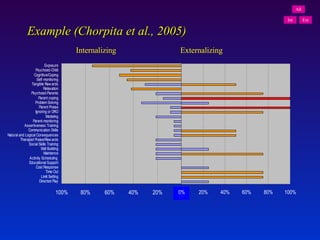

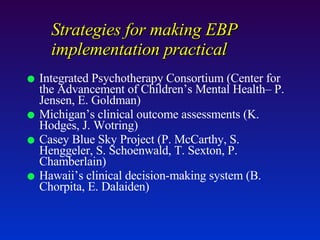

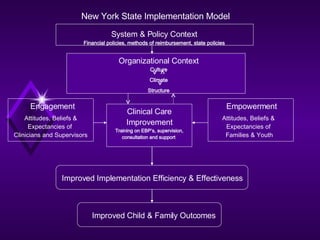

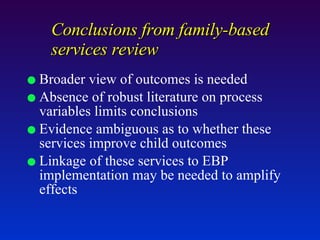

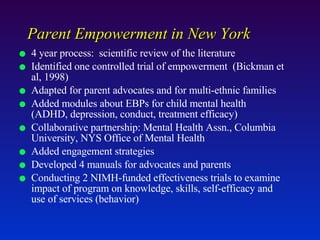

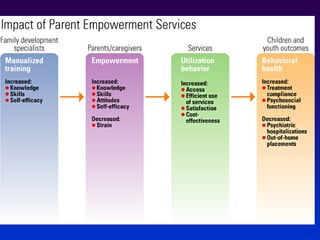

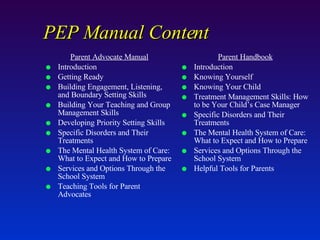

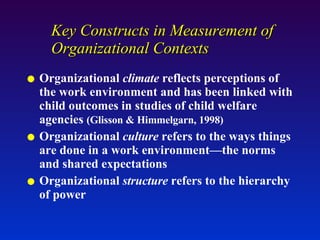

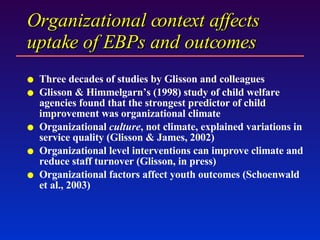

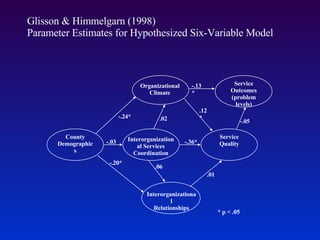

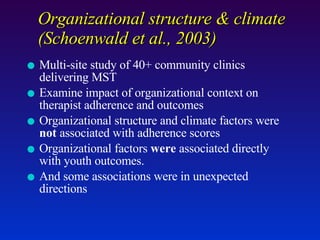

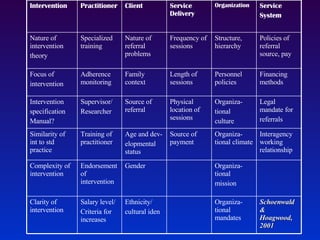

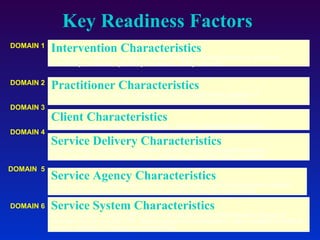

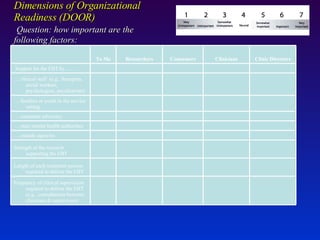

The document discusses the history and current state of evidence-based practices in children's mental health. It notes that while research has identified hundreds of evidence-based therapies and interventions, many children still have unmet mental health needs. It summarizes the levels of evidence for different psychosocial and pharmacological treatments, as well as home- and community-based services. However, it states that significant challenges remain in implementing evidence-based practices into real-world mental health systems and services.