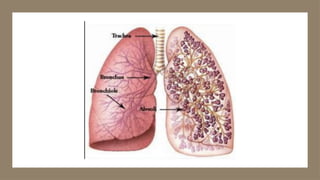

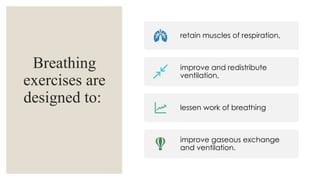

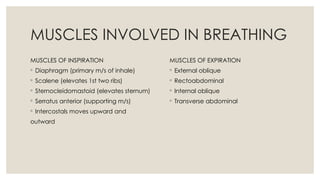

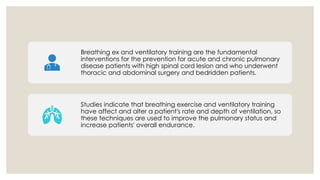

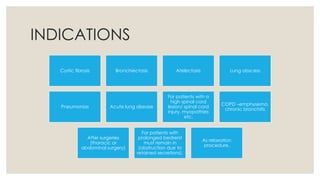

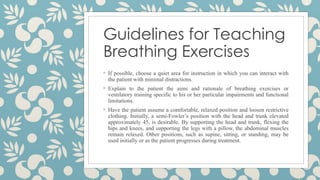

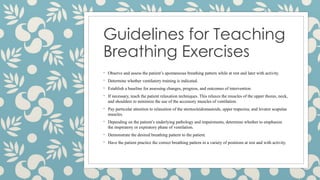

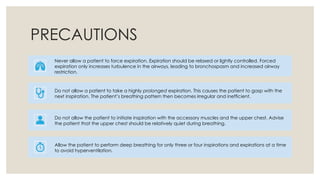

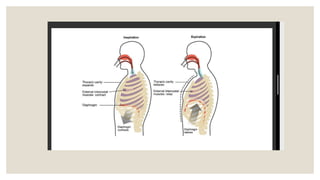

The document outlines the breathing process and emphasizes the importance of breathing exercises, which can enhance lung function and aid patients with both healthy and impaired lungs. It details various breathing techniques, their goals, contraindications, and guidelines for teaching, while also highlighting the benefits for specific patient conditions. Additionally, it discusses the mechanics of breathing muscles and introduces different exercises aimed at improving ventilation and respiratory efficiency.