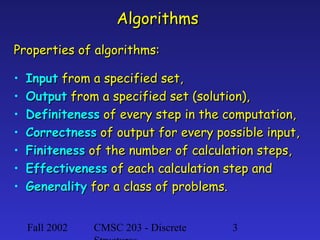

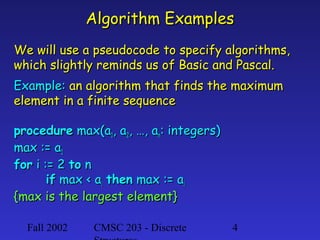

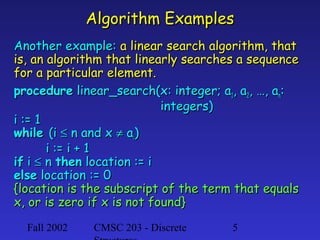

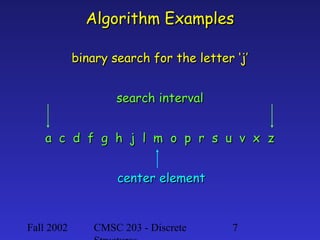

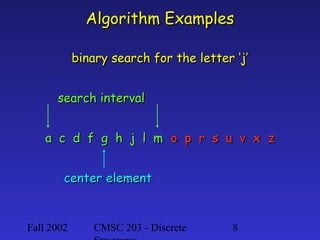

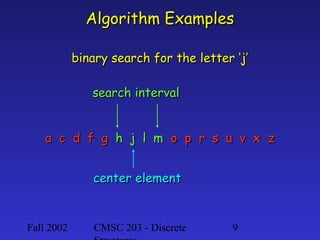

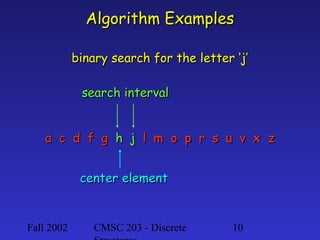

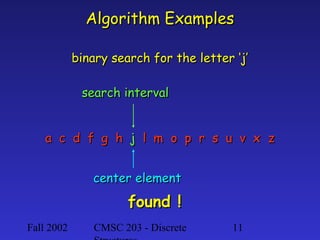

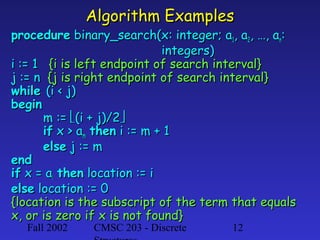

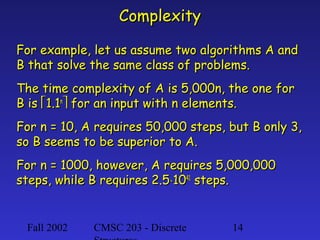

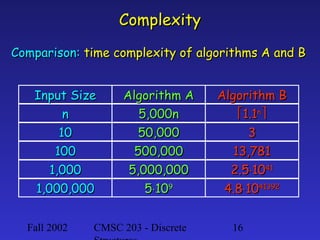

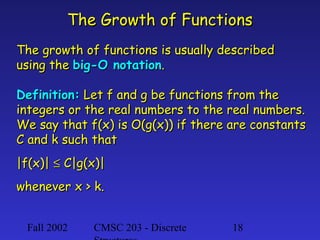

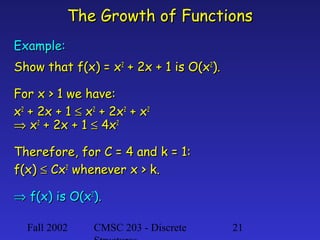

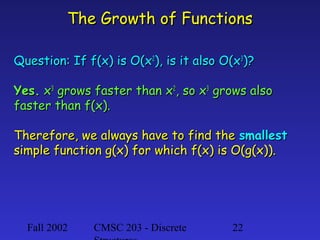

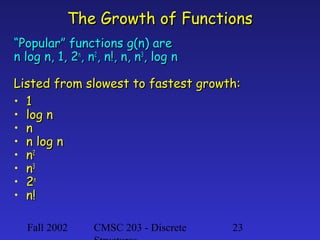

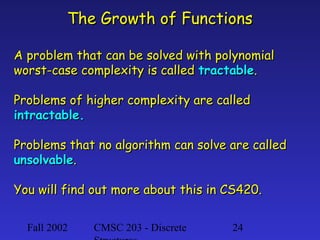

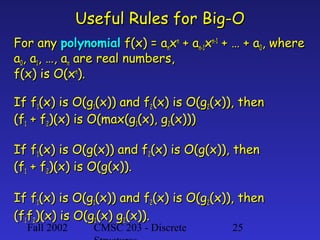

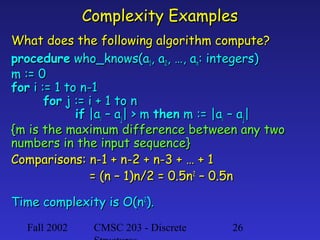

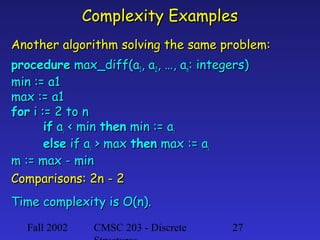

This document introduces algorithms and their properties. It defines an algorithm as a precise set of instructions to perform a computation or solve a problem. Key properties of algorithms are discussed such as inputs, outputs, definiteness, correctness, finiteness, effectiveness and generality. Examples are given of maximum finding, linear search and binary search algorithms using pseudocode. The document discusses how algorithm complexity grows with input size and introduces big-O notation to analyze asymptotic growth rates of algorithms. It provides examples of analyzing time complexities for different algorithms.