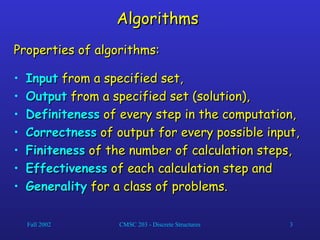

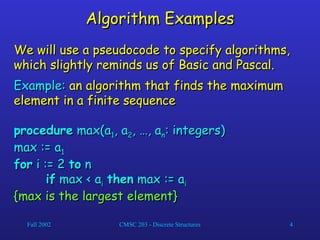

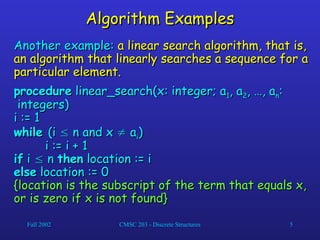

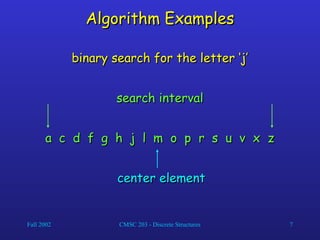

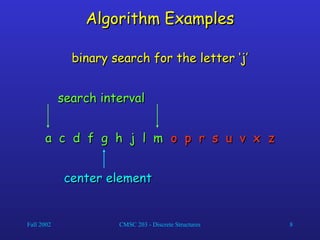

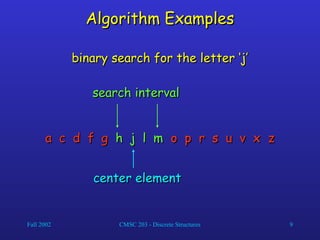

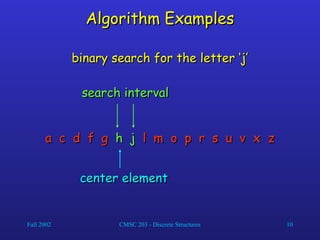

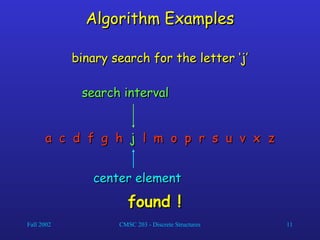

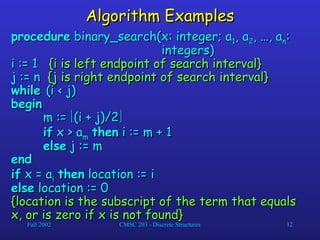

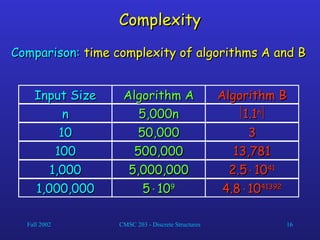

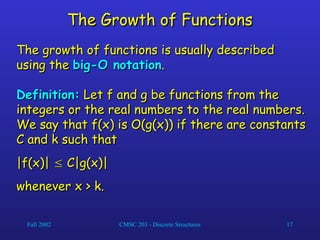

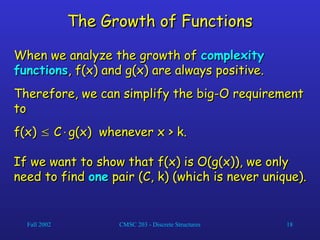

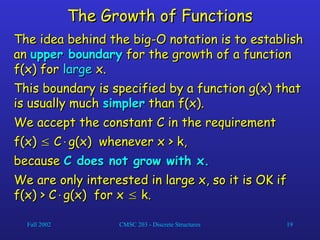

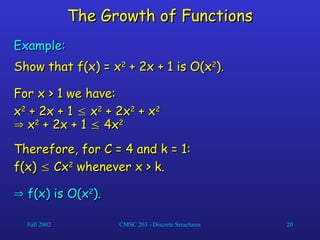

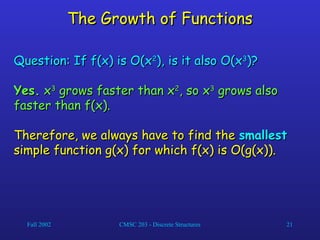

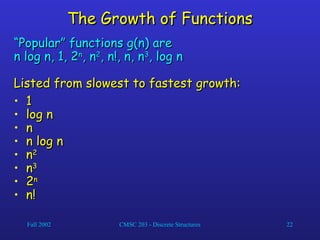

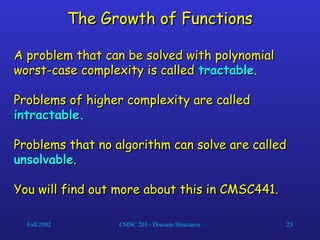

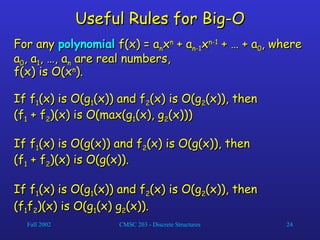

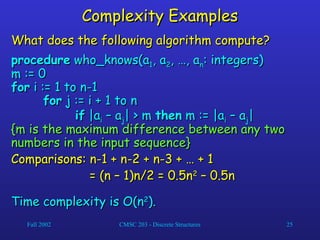

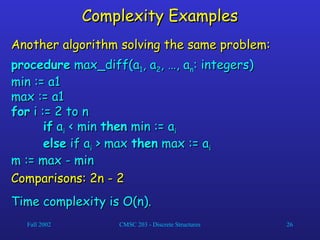

The document provides an overview of algorithms, defining them as a finite set of precise instructions for computation and discussing their essential properties such as input, output, correctness, and effectiveness. It includes examples of algorithms like linear and binary search, highlighting their efficiency differences and the significance of time complexity in relation to input size. Additionally, it introduces big-O notation for analyzing the growth of functions and categorizes problems based on their complexity.