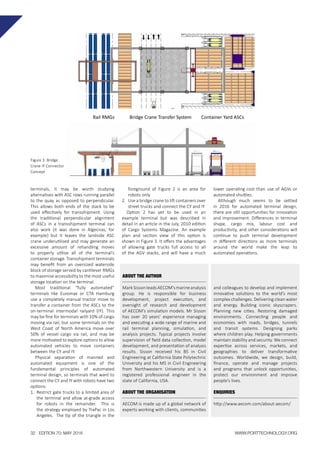

Automated stacking cranes (ASCs) are a common approach for automated container terminals. ASCs pick containers from the end of stacks in the container yard and transfer them to or from desired storage positions perpendicular to the quay. This separation of gate and vessel traffic allows for automated transport between the quay and yard. While automated terminals have struggled with quay crane productivity, manual shuttles have achieved high productivity and require less testing than fully automated options. Terminal layout and cargo mix, such as the proportion of transshipment or rail cargo, influence the best horizontal transport and ASC alignment options.