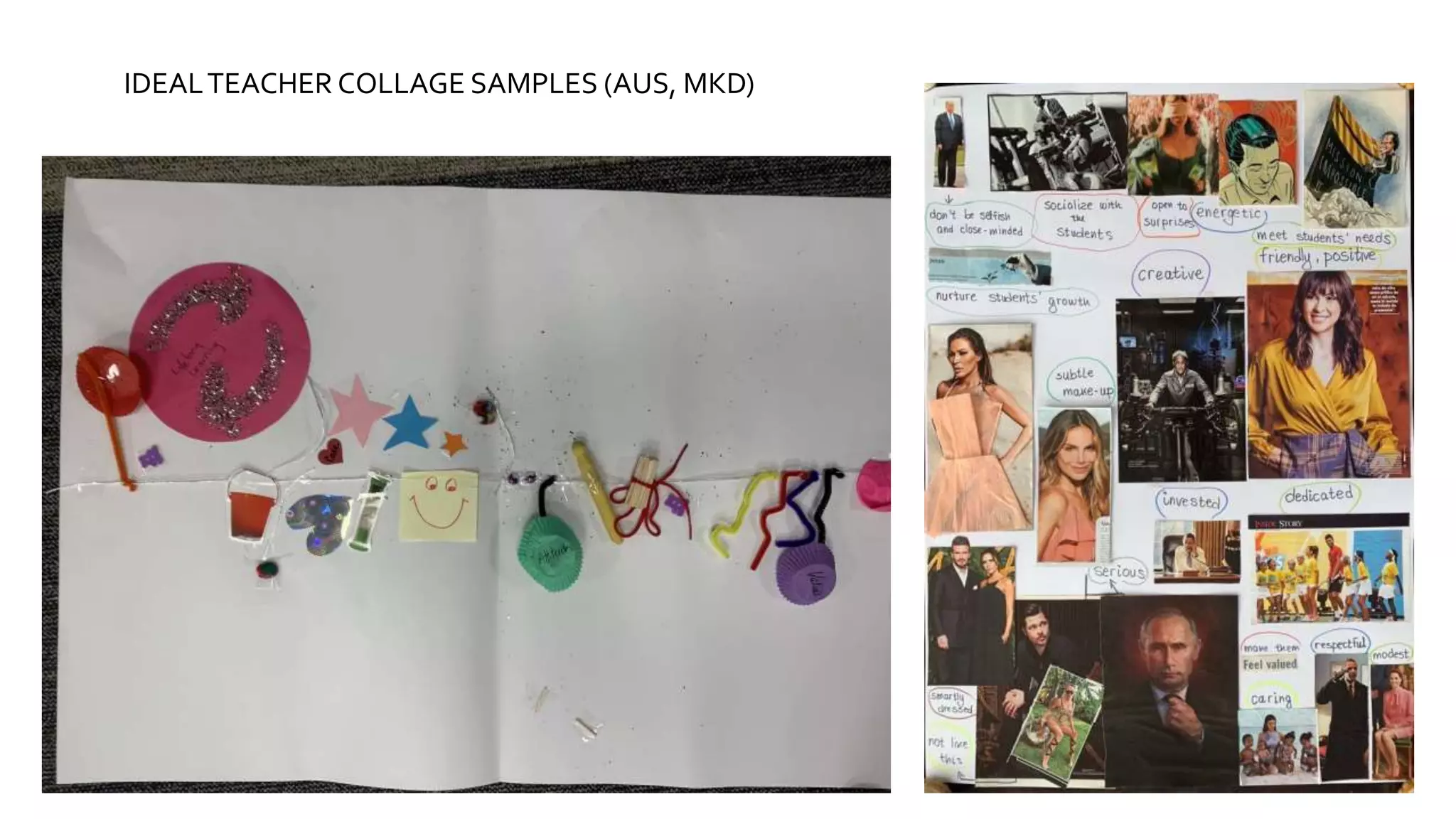

The document summarizes a study on supporting professional agency in Australian and Macedonian pre-service teachers. The study used arts-based reflection methods including collaborative drawings and collages to explore pre-service teachers' visions of an ideal classroom and teacher qualities. Findings showed participants could clearly articulate ideal teacher qualities and factors supporting agency development, though Australian participants demonstrated greater ability to identify obstacles. The study concluded arts-based reflection promotes prerequisites for agentic behavior like deep reflection and connectedness. It also suggested reflection strengthens with practice and supports knowledge and identity development aligned with models of teacher development.

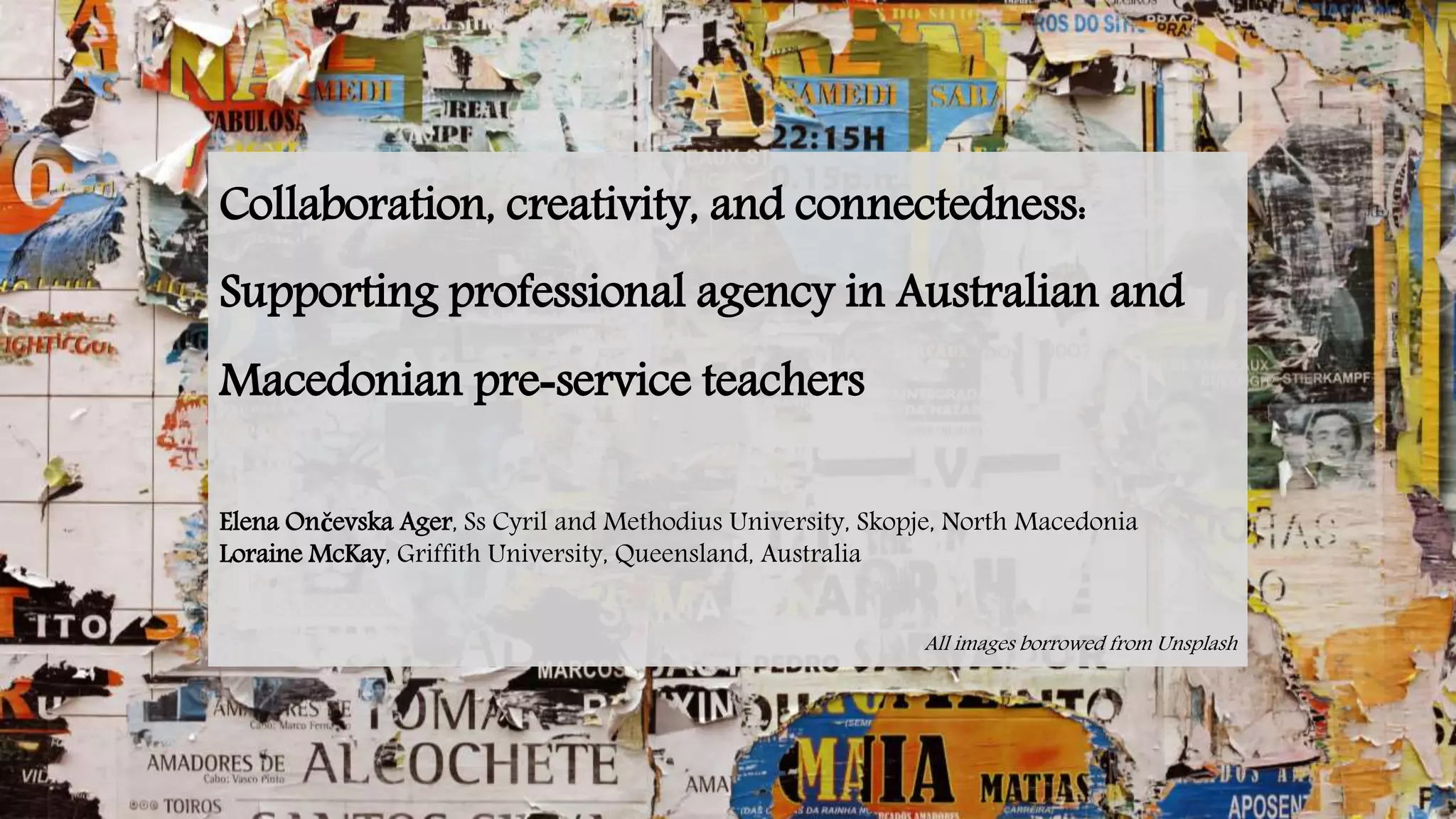

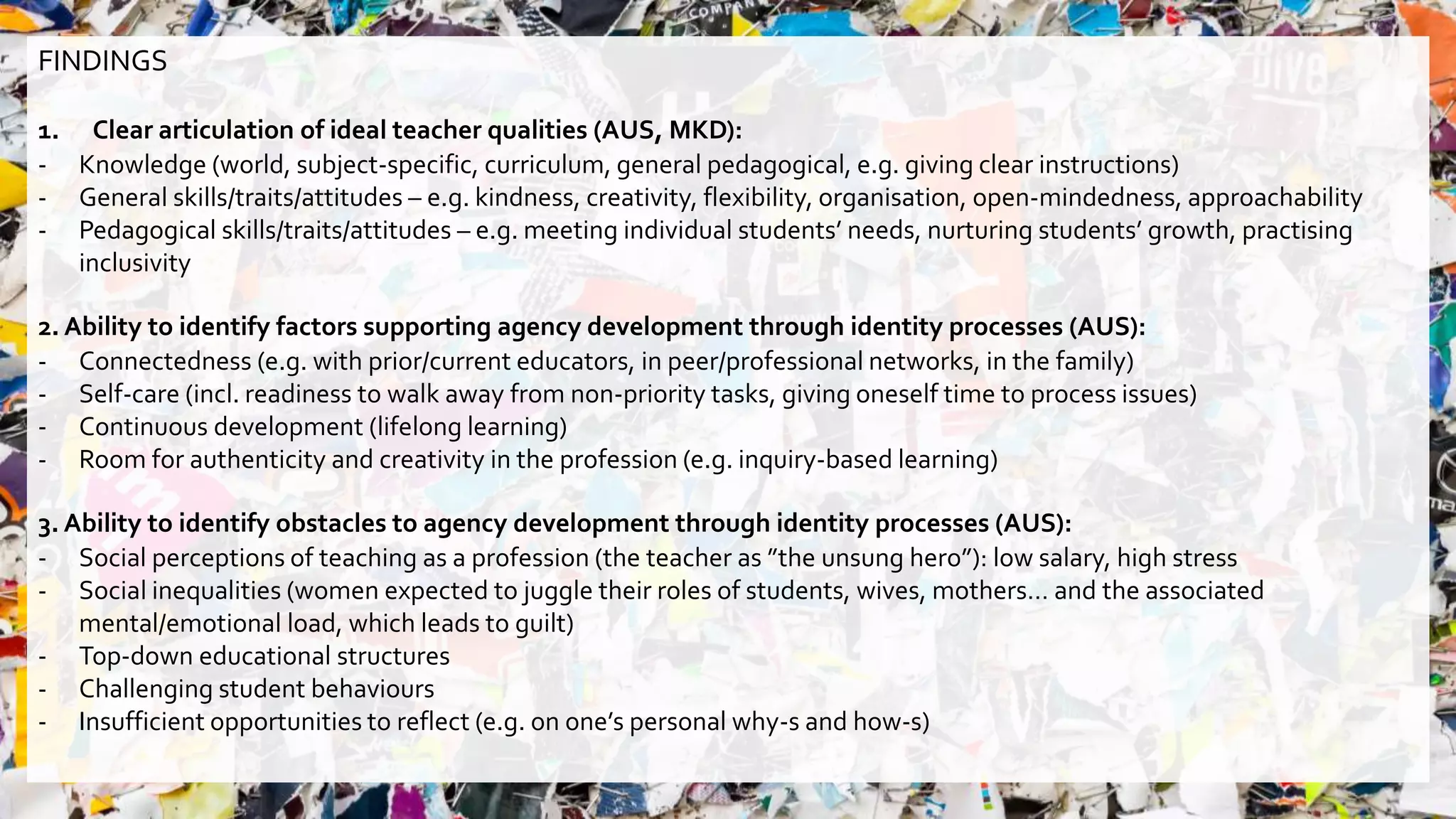

![IDEALTEACHER INDIVIDUAL REFLECTION EXCERPTS (AUS, MKD)

Quality: Adaptability through strength

[…]The wave is able to move and dance because it is supported by a body of water beneath

it. It is a part of something bigger than itself. I feel that my life experiences (specifically, all

the times I feel hugely out of my depth, but then manage to […] do what needs to be done

and do it well) have showed me that I have an inner strength that I am able to rely on when I

need it.Along with my experiences, my family, my dear friends, and, in fact, the entire

teaching profession, all act as my ocean in differing ways. My family hold and support me

and provide a place to disengage from the dramas of university and teaching. My friends

share my passion for children and provide space for me to dream and imagine where my life

could lead, and the teaching industry shows me that I am not alone in this passion to

empower the next generation. I am a wave, moving, dancing, exploring, but I am not alone.

Quality: Empathy

Understanding and sharing [in

teaching] are vital. […]The teacher

should be the primary [role model] for

[practicing] empathy, which is shown

by the way the teacher interacts with

the students. [I remember talking] to

[a student who was mocked for her

height] Jana’s friends during the

classroom observation [session]

[about] height not [being] the most

important thing in the world. […] [I

shared that] I was the same height as

her when I was her age and am now all

grown up.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ecer2021arts-basedreflection-210815153444/75/Arts-based-reflection-8-2048.jpg)

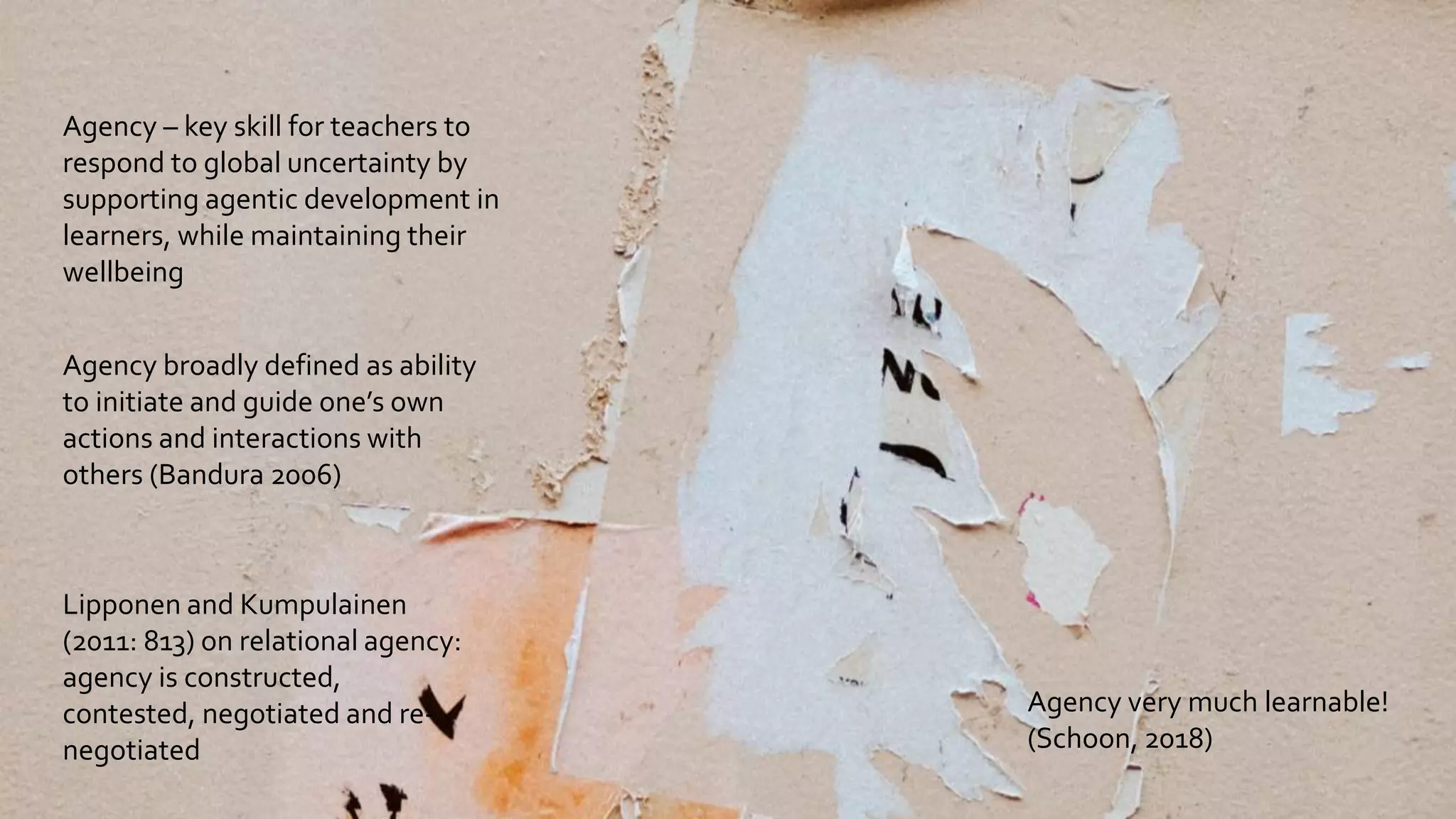

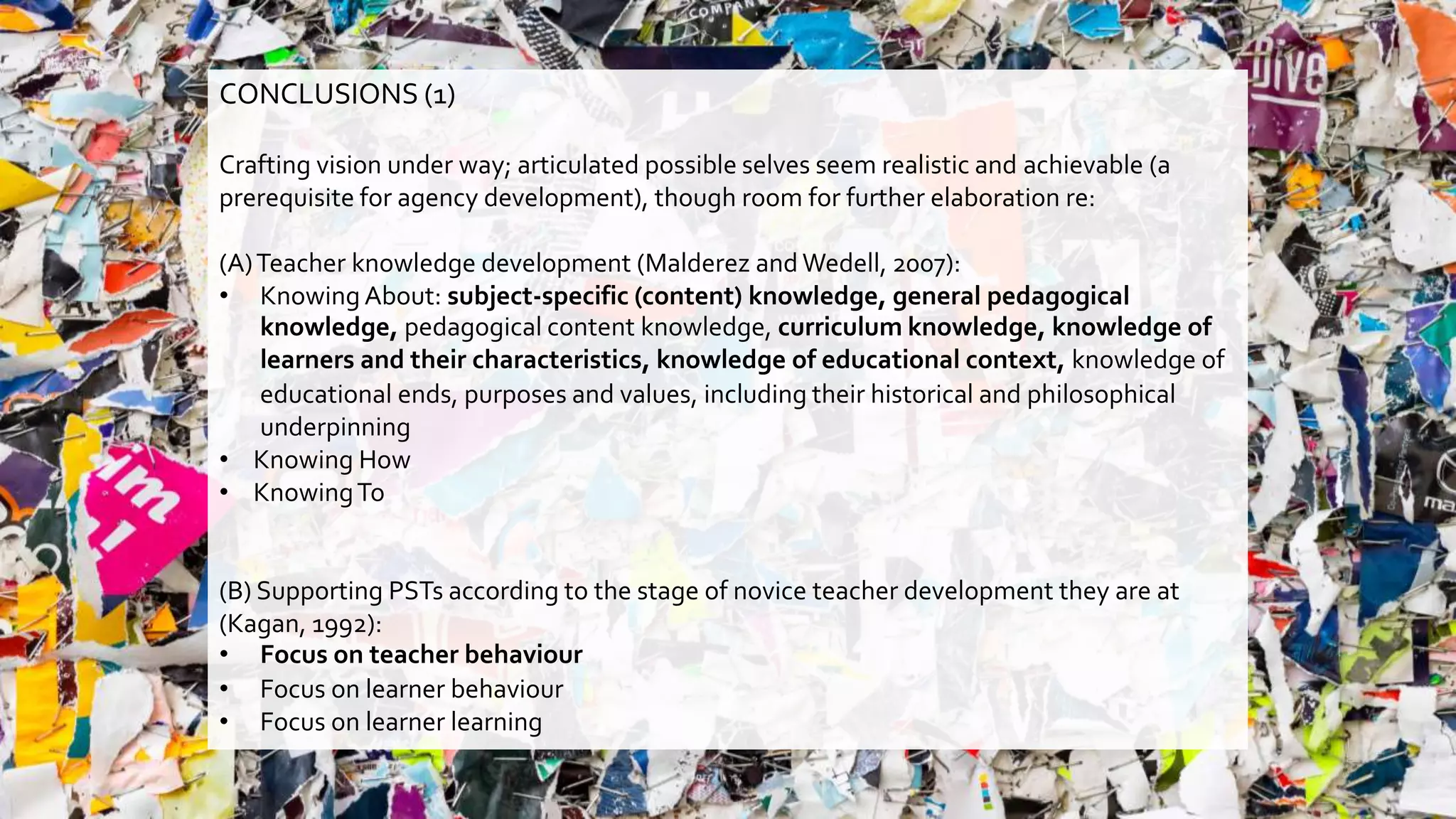

![CONCLUSIONS (2)

Arts-based reflection worth considering onTE programmes for its potential to

promote the following prerequisites for agentic behaviour (McKay, 2021):

• Deep, personalised reflection to fuel knowledge/identity development processes

• Connectedness

• Wellbeing (e.g. reflecting on character strengths elicits positive emotions and

promotes engagement following Seligman’s PERMA model of wellbeing, 2011)

• Personal accountability: “Reflection was absolutely imperative when I was on

prac. It is so easy to blame the kids, or the weather, or anything else for a bad

lesson or a bad day but the buck stops with you and there's always something you

can do to improve. […] Reflecting on what went well and what didn't, then

actioning your reflections is the most effective way of improving your practice.”

Reflection, as our comparative data suggests, is learnable: its robustness improves

with practice.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ecer2021arts-basedreflection-210815153444/75/Arts-based-reflection-11-2048.jpg)