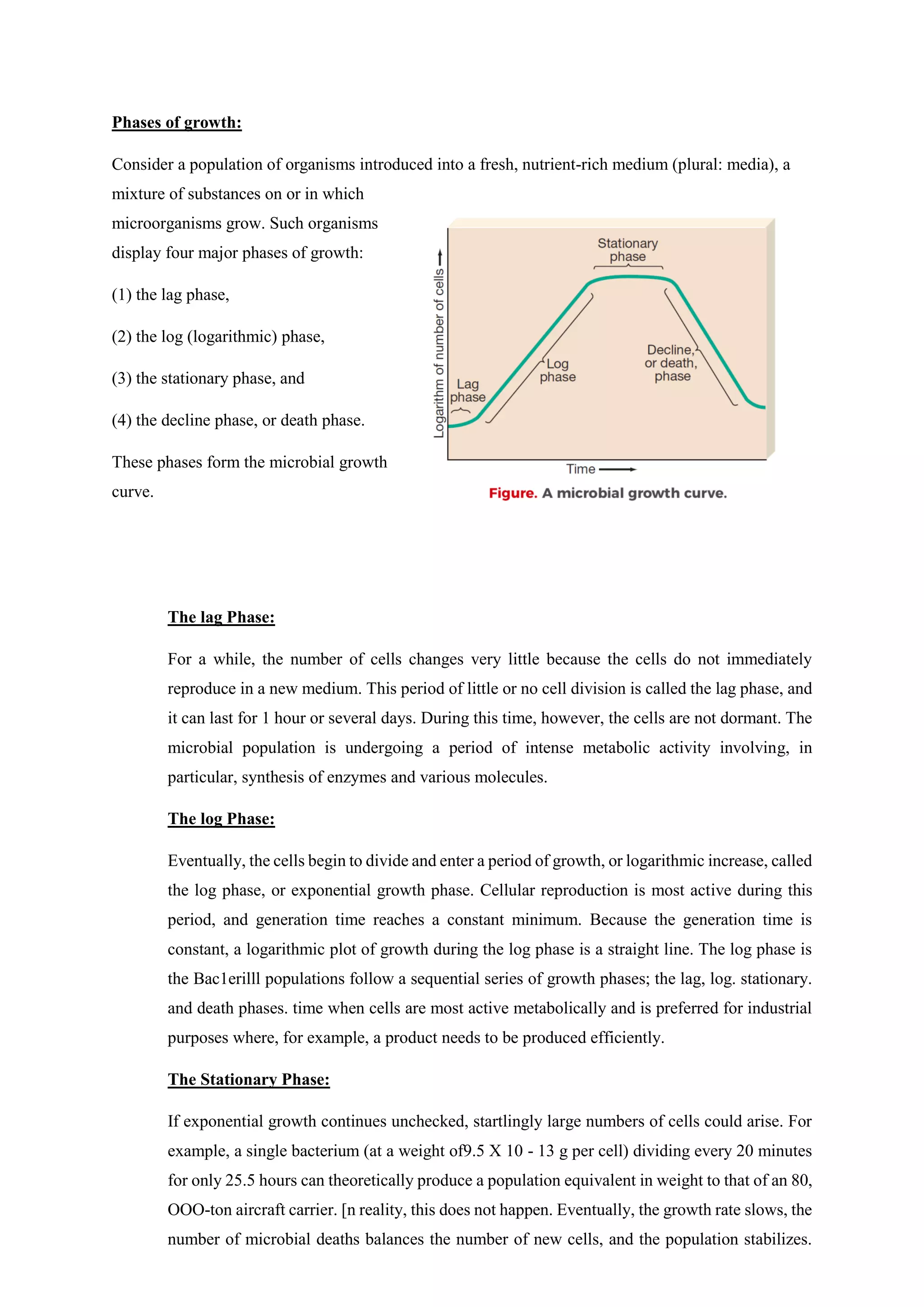

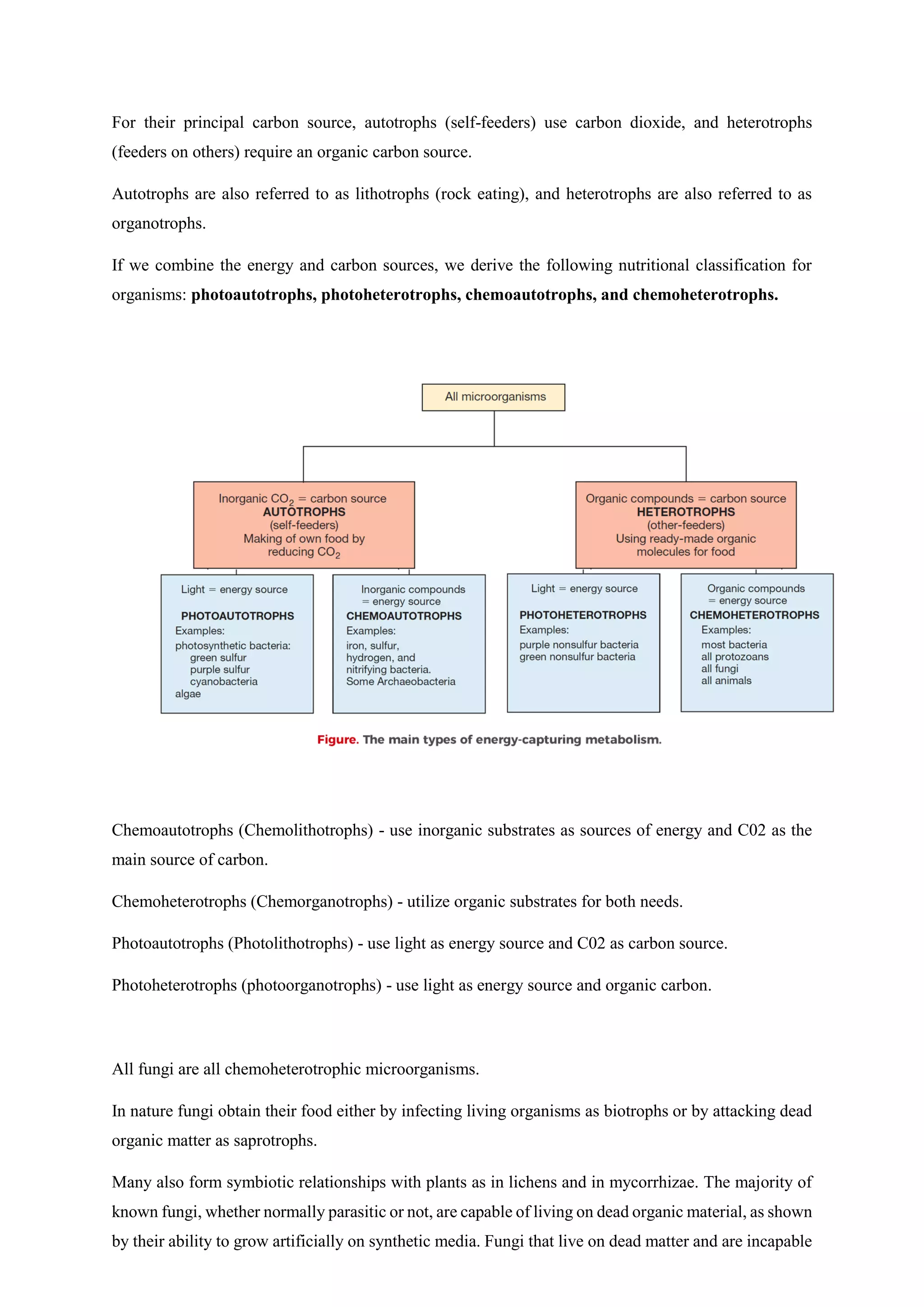

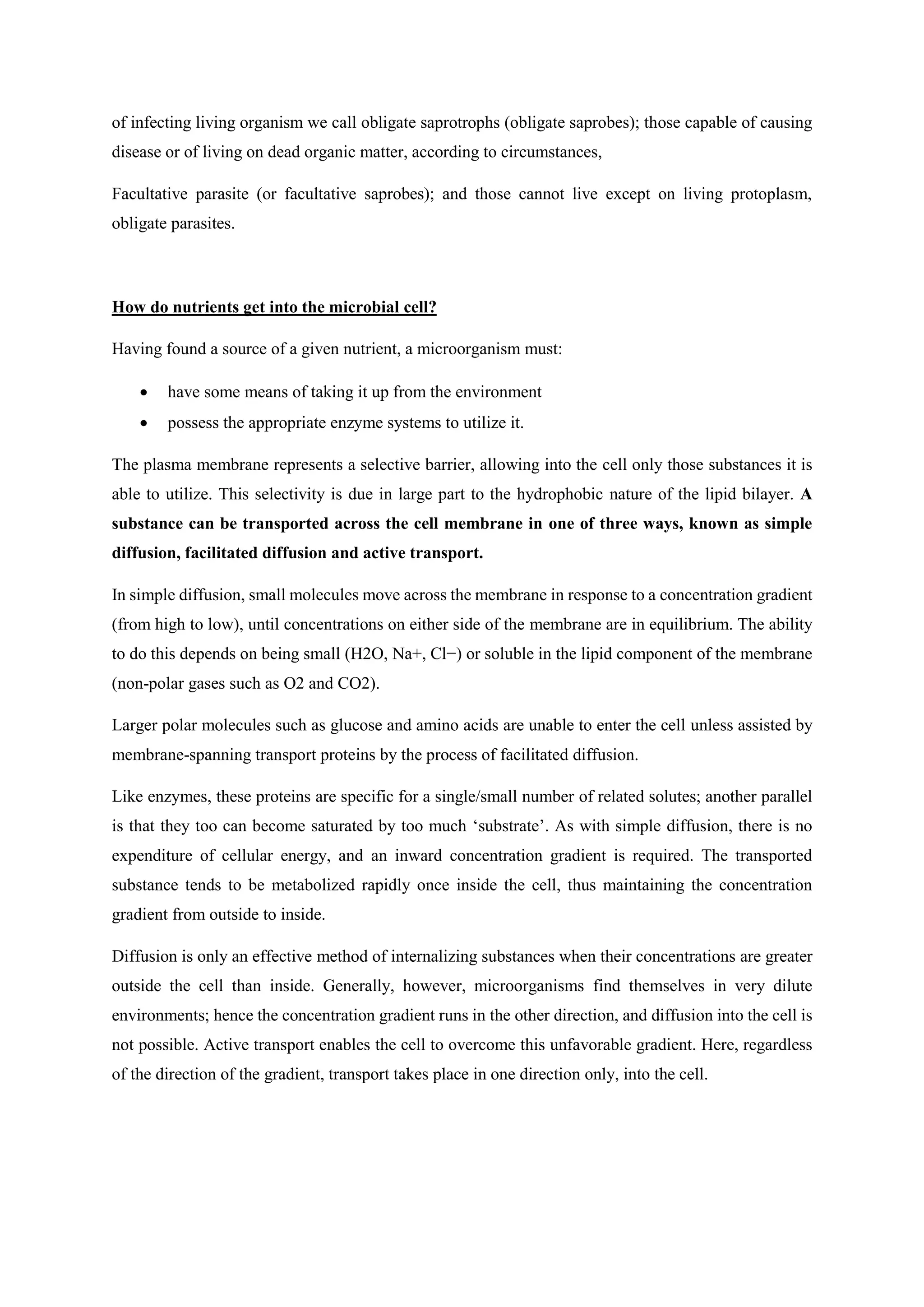

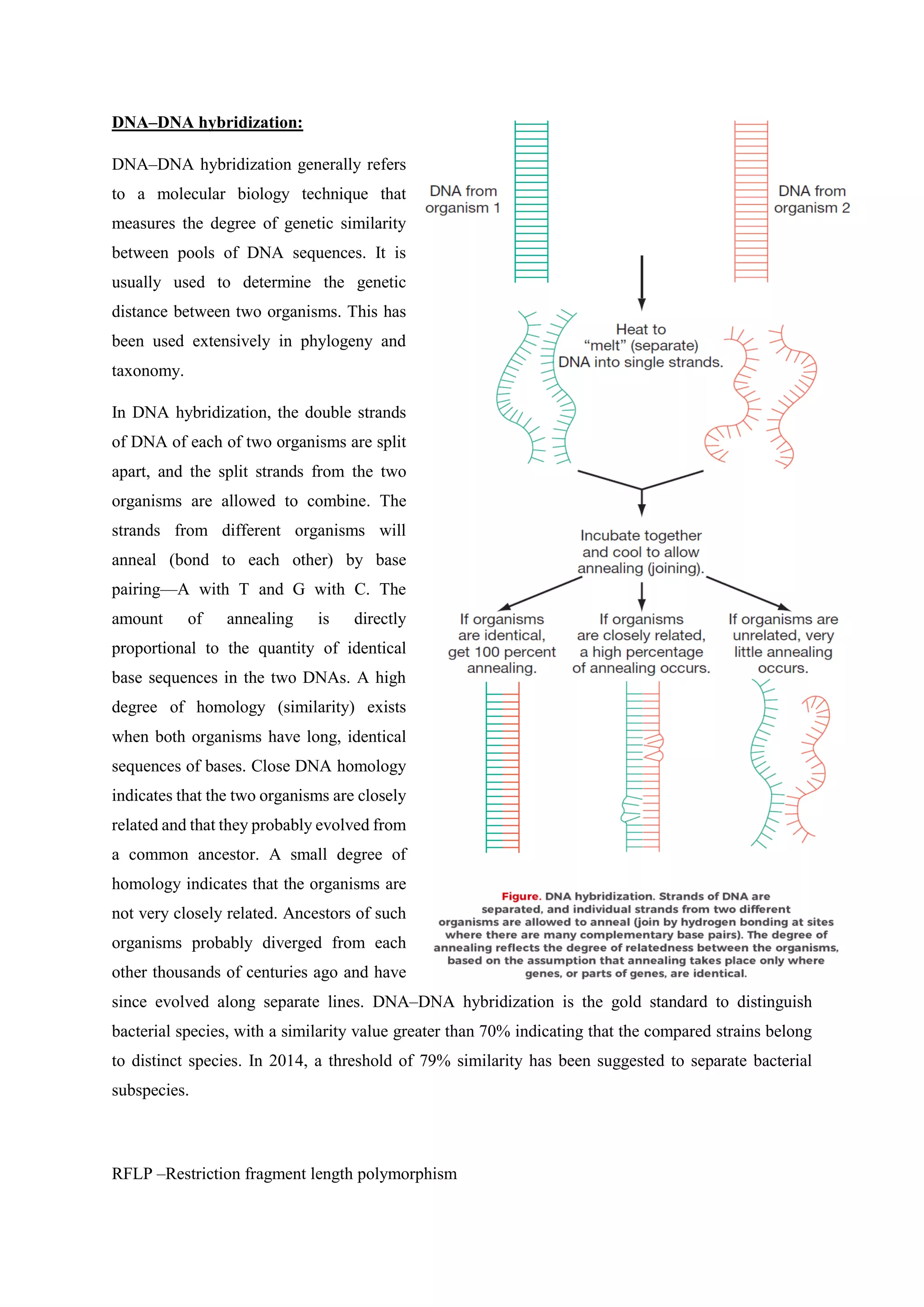

The document covers microbial growth, nutrition, and methods of cell division, including binary fission and budding. It outlines phases of microbial growth, factors affecting growth, and the nutritional classification of microorganisms. Additionally, it discusses how nutrients are transported into microbial cells and describes various growth media used for bacterial cultivation.