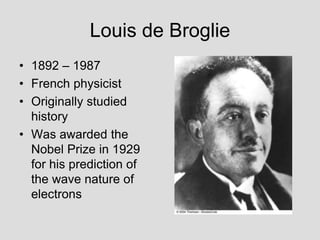

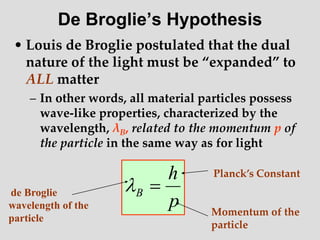

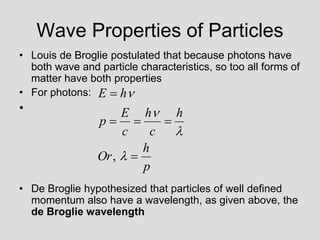

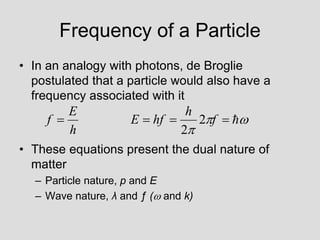

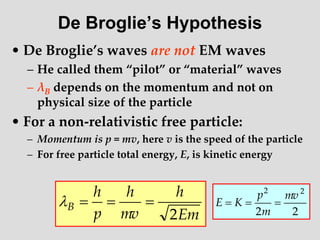

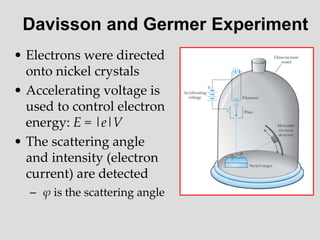

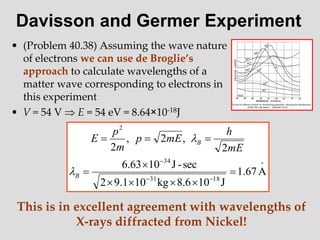

- Louis de Broglie hypothesized that all matter exhibits both wave and particle properties, with a wavelength inversely proportional to momentum, just as light does.

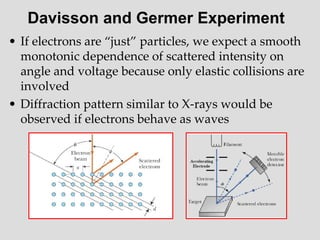

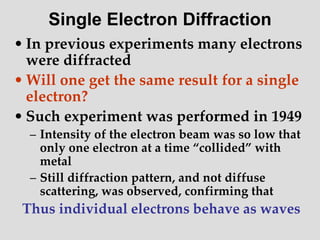

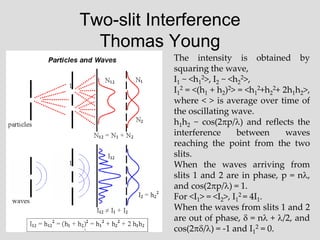

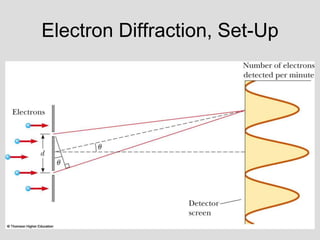

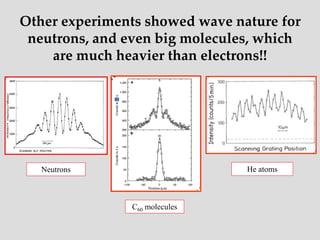

- Experiments observing diffraction and interference of electrons, neutrons, atoms and molecules provided evidence that matter has wave-like properties consistent with a de Broglie wavelength, demonstrating the wave-particle duality of all matter.

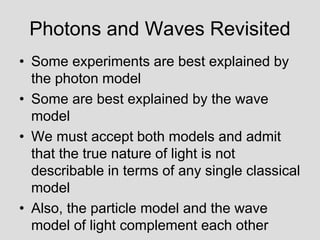

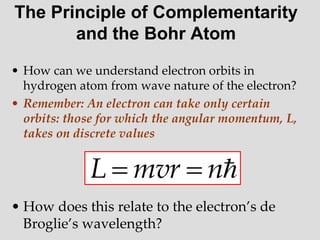

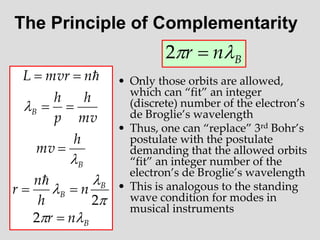

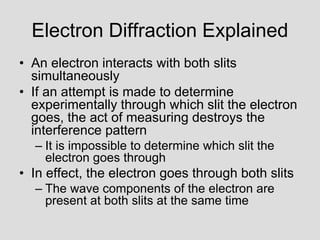

- The principle of complementarity states that matter and light cannot be fully described as either purely waves or particles, as the two models complement each other and neither is complete. Observing one property precludes observation of the other.

![Addition of Two Waves

)

2

sin(

)

2

cos(

2

)

sin(

)

sin(

)

,

(

t

kx

A

t

kx

A

t

kx

A

t

x

y

t

kx

A

t

kx

A

t

kx

A

t

x

y

cos

sin

2

)

sin(

)

sin(

)

,

(

Two sine waves traveling in the same direction:

Constructive and Destructive Interference

Two sine waves traveling in opposite directions create a standing wave

Two sine waves with different frequencies: Beats

]

2

(

2

(

sin[

]

)

2

/

(

)

2

/

cos[(

2

]

2

(

2

(

sin[

]

2

(

2

(

cos[

2

)

sin(

)

sin(

)

,

(

)

2

1

)

2

1

)

2

1

)

2

1

)

2

1

)

2

1

2

2

1

1

t

x

k

k

t

x

k

A

t

x

k

k

t

x

k

k

A

t

x

k

A

t

x

k

A

t

x

y

](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/12377224-230419105258-c3e48f68/85/12377224-ppt-37-320.jpg)

![Beat Notes and Group Velocity, vg

This represents a beat note with the amplitude of the beat moving at speed

dk

d

v

v

k

v

g

g

:

waves

of

on

distributi

continuous

of

ion

superposit

For

/

)

2

/

/(

)

2

/

(

]

2

(

2

(

sin[

]

)

2

/

(

)

2

/

cos[(

2

)

,

(

)

2

1

)

2

1

t

x

k

k

t

x

k

A

t

x

y

](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/12377224-230419105258-c3e48f68/85/12377224-ppt-38-320.jpg)

![Beats and Pulses

Two tuning forks are struck simultaneously. The vibrate at 512 and 768 Hz.

(a) What is the separation between peaks in the beat envelope?

(b) What is the velocity of the beat envelope?

(a)

The rapidly oscillating wave is multiplied by a more slowly varying envelope

with wave vector

]

2

(

2

(

sin[

]

)

2

/

(

)

2

/

cos[(

2

)

,

(

)

2

1

)

2

1

t

x

k

k

t

x

k

A

t

x

y

phase

beat

beat

beat

beat

beat

phase

phase

phase

phase

phase

phase

v

v

so

th

ofwaveleng

t

independen

is

sound

of

speed

ce

result

Expected

k

v

b

m

k

notes

beat

between

ce

Dis

m

k

k

k

m

v

f

v

k

m

v

f

v

k

mph

s

m

sound

of

speed

the

is

v

f

f

k

v

k

k

k

sin

344

)

35

.

9

03

.

14

/(

)

512

768

(

2

)

2

/

/(

)

2

/

(

)

(

70

.

2

33

.

2

/

2

/

2

:

tan

33

.

2

2

/

)

35

.

9

0

.

14

(

2

/

)

(

35

.

9

344

/

512

2

/

2

/

03

.

14

344

/

768

2

/

2

/

)

770

(

/

344

,

,

)

/

2

/(

2

/

2

/

)

(

2

/

1

1

2

1

1

1

1

1

2

2

2

1

2

](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/12377224-230419105258-c3e48f68/85/12377224-ppt-40-320.jpg)