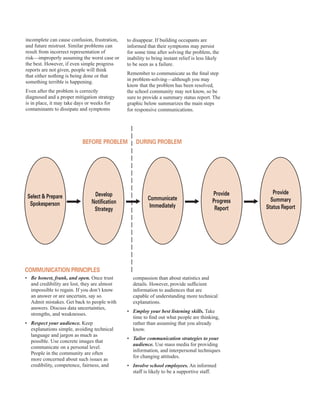

This document provides guidance on indoor air quality (IAQ) in schools. It discusses why IAQ is important for schools, noting potential health impacts on students and staff from poor IAQ. Schools face unique IAQ challenges due to high occupancy levels, tight budgets, and various pollutant sources. The document outlines how IAQ problems can develop from interactions between pollutant sources, heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) systems, pollutant pathways, and building occupants. It provides strategies for communicating about, diagnosing, and resolving IAQ issues in a practical and cost-effective manner.