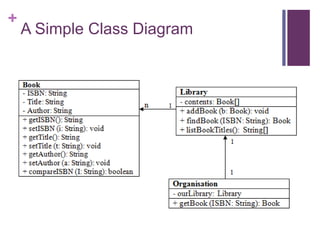

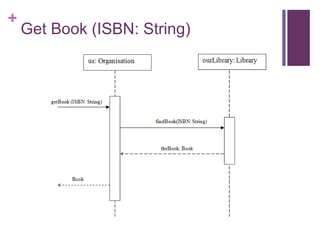

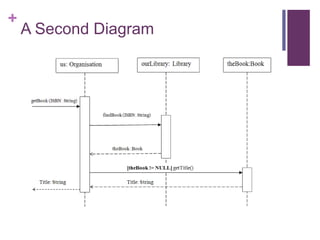

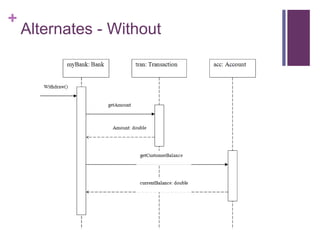

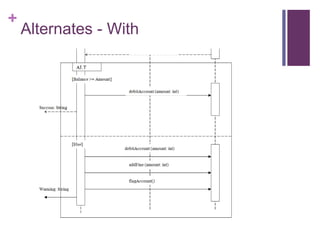

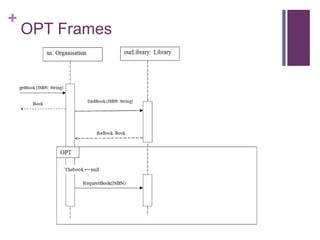

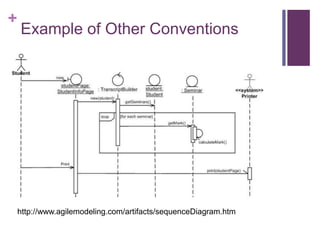

The document discusses sequence diagrams and their use in system analysis and design. Sequence diagrams show the interactions between objects in a system and the order that messages and method calls are made. They can incorporate elements like alternate paths using frames to represent conditional logic. While not required, sequence diagrams are useful for testing a system design by validating interactions and method accessibility between classes.