This section discusses three-dimensional stress and strain. It introduces the traction vector and its components, which are represented by the stress tensor. Cauchy's law relates the traction vector on a surface to the stress tensor and the surface normal. The stress tensor transforms between coordinate systems according to the tensor transformation rule. Stresses can be resolved into normal and shear components on any plane through a point.

![Section 7.2

Solid Mechanics Part II Kelly203

[ ]

⎥

⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢

⎢

⎣

⎡

=

333231

232221

131211

σσσ

σσσ

σσσ

σij (7.2.4)

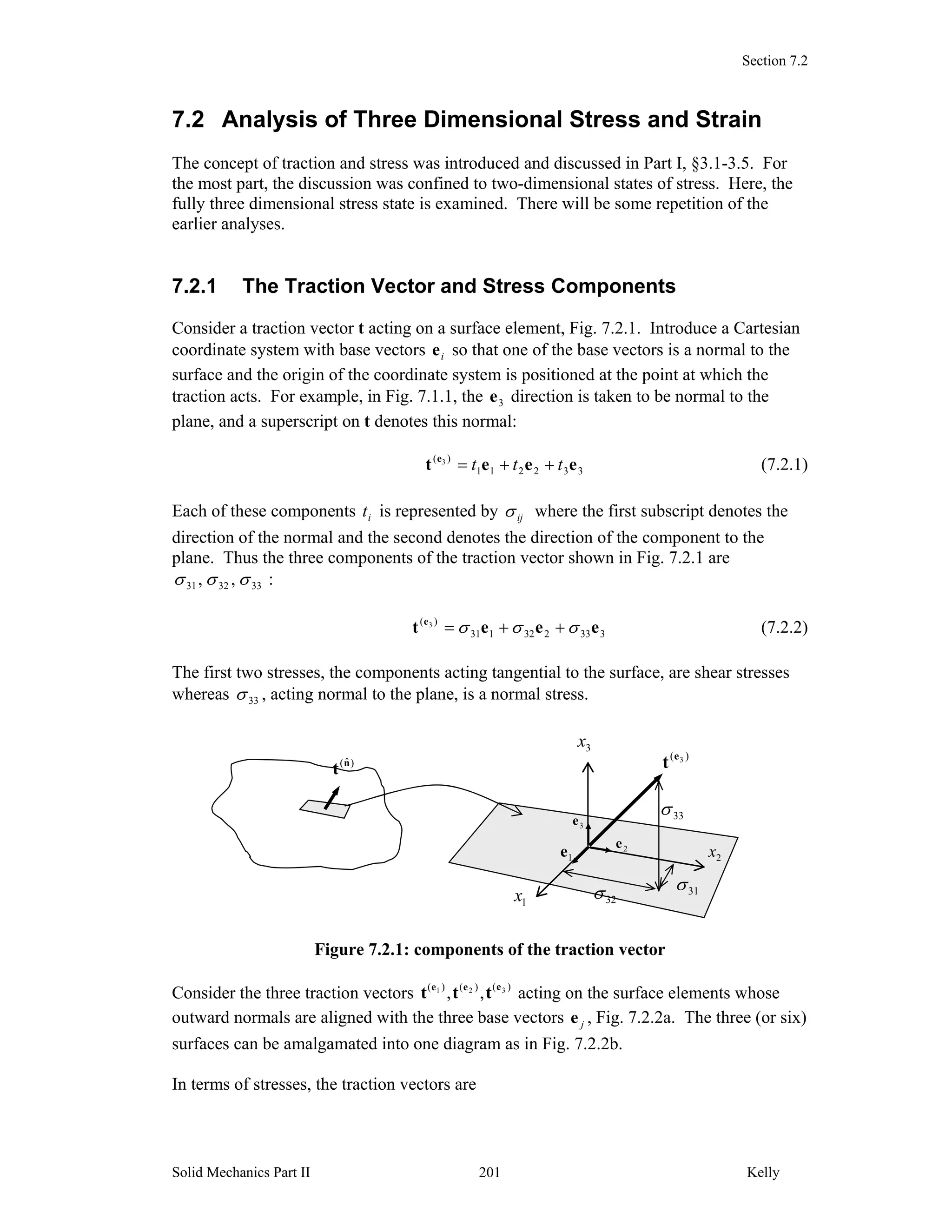

It is important to realise that, if one were to take an element at some different orientation

to the element in Fig. 7.2.3, but at the same material particle, for example aligned with

the axes 321 ,, xxx ′′′ shown in Fig. 7.2.4, one would then have different tractions acting and

the nine stresses would be different also. The stresses acting in this new orientation can

be represented by a new matrix:

[ ]

⎥

⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢

⎢

⎣

⎡

′′′

′′′

′′′

=′

333231

232221

131211

σσσ

σσσ

σσσ

σij (7.2.5)

Figure 7.2.4: the stress components with respect to a Cartesian coordinate system

different to that in Fig. 7.2.3

7.2.2 Cauchy’s Law

Cauchy’s Law, which will be proved below, states that the normal to a surface, iin en = ,

is related to the traction vector iit et n

=)(

acting on that surface, according to

jjii nt σ= (7.2.6)

Writing the traction and normal in vector form and the stress in 33× matrix form,

[ ] [ ] [ ]

⎥

⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢

⎢

⎣

⎡

=

⎥

⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢

⎢

⎣

⎡

=

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎣

⎡

=

3

2

1

333231

232221

131211

)(

3

)(

2

)(

1

)(

,,

n

n

n

n

t

t

t

t iiji

σσσ

σσσ

σσσ

σ

n

n

n

n

(7.2.7)

and Cauchy’s law in matrix notation reads

1x′

2x′

3x′

11σ′

12σ′

13σ′31σ′

33σ′

32σ′

22σ′

21σ′

23σ′](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/073delasticity023dstressstrain-170829112447/85/07-3-d_elasticity_02_3d_stressstrain-3-320.jpg)

![Section 7.2

Solid Mechanics Part II Kelly205

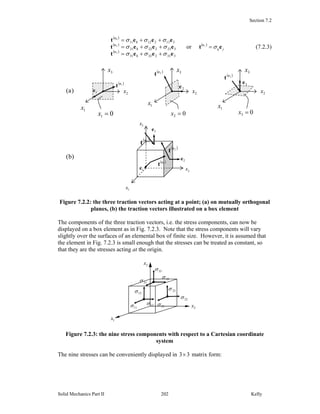

Figure 7.2.6: the normal and shear stress acting on an arbitrary plane through a

point

Example

The state of stress at a point with respect to a Cartesian coordinates system 3210 xxx is

given by:

[ ]

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎣

⎡

−

−=

123

221

312

ijσ

Determine:

(a) the traction vector acting on a plane through the point whose unit normal is

321 )3/2()3/2()3/1( eeen −+=

(b) the component of this traction acting perpendicular to the plane

(c) the shear component of traction on the plane

Solution

(a) From Cauchy’s law,

⎥

⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢

⎢

⎣

⎡

−

−

=

⎥

⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢

⎢

⎣

⎡

−⎥

⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢

⎢

⎣

⎡

−

−=

⎥

⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢

⎢

⎣

⎡

⎥

⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢

⎢

⎣

⎡

=

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎣

⎡

3

9

2

3

1

2

2

1

123

221

312

3

1

3

2

1

332313

322212

312111

)(

3

)(

2

)(

1

n

n

n

t

t

t

σσσ

σσσ

σσσ

n

n

n

so that 321

)(

ˆ3)3/2( eeet n

−+−= .

(b) The component normal to the plane is

.4.29/22)3/2()3/2(3)3/1)(3/2()(

≈=++−=⋅= nt n

Nσ

(c) The shearing component of traction is

( ) ( ) ( )[ ] ( )[ ]{ } 1.213

2/12

9

22222

3

222)(

≈−−++−=−= NS σσ n

t

■

3x

2x

1x

n

( )n

tNσ

Sσ](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/073delasticity023dstressstrain-170829112447/85/07-3-d_elasticity_02_3d_stressstrain-5-320.jpg)

![Section 7.2

Solid Mechanics Part II Kelly207

7.2.3 The Stress Tensor

Cauchy’s law 7.2.9 is of the same form as 7.1.24 and so by definition the stress is a

tensor. Denote the stress tensor in symbolic notation by σ . Cauchy’s law in symbolic

form then reads

nσt = (7.2.15)

Further, the transformation rule for stress follows the general tensor transformation rule

7.1.31:

[ ] [ ][ ][ ]

[ ] [ ][ ][ ]QσQσ

QσQσ

T

T

=′=′

′=′=

K

K

pqqjpiij

pqjqipij

QQ

QQ

σσ

σσ

Stress Transformation Rule (7.2.16)

As with the normal and traction vectors, the components and hence matrix representation

of the stress changes with coordinate system, as with the two different matrix

representations 7.2.4 and 7.2.5. However, there is only one stress tensor σ at a point.

Another way of looking at this is to note that an infinite number of planes pass through a

point, and on each of these planes acts a traction vector, and each of these traction vectors

has three (stress) components. All of these traction vectors taken together define the

complete state of stress at a point.

Example

The state of stress at a point with respect to an 3210 xxx coordinate system is given by

[ ]

⎥

⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢

⎢

⎣

⎡

−

−=

120

231

012

ijσ

(a) What are the stress components with respect to axes 3210 xxx ′′′ which are obtained

from the first by a o

45 rotation (positive counterclockwise) about the 2x axis, Fig.

7.2.8?

(b) Use Cauchy’s law to evaluate the normal and shear stress on a plane with normal

( ) ( ) 31 2/12/1 een += and relate your result with that from (a)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/073delasticity023dstressstrain-170829112447/85/07-3-d_elasticity_02_3d_stressstrain-7-320.jpg)

![Section 7.2

Solid Mechanics Part II Kelly208

Figure 7.2.8: two different coordinate systems at a point

Solution

(a) The transformation matrix is

[ ]

( ) ( ) ( )

( ) ( ) ( )

( ) ( ) ( ) ⎥

⎥

⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎣

⎡

−

=

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎣

⎡

′′′

′′′

′′′

=

2

1

2

1

2

1

2

1

332313

322212

312111

0

010

0

,cos,cos,cos

,cos,cos,cos

,cos,cos,cos

xxxxxx

xxxxxx

xxxxxx

Qij

and IQQ =T

as expected. The rotated stress components are therefore

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎣

⎡

−

−=

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎣

⎡

−⎥

⎥

⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎣

⎡

−

−

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎣

⎡ −

=

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎣

⎡

′′′

′′′

′′′

2

3

2

1

2

1

2

1

2

3

2

1

2

3

2

3

2

1

2

1

2

1

2

1

2

1

2

1

2

1

2

1

333231

232221

131211

3

0

010

0

120

231

012

0

010

0

σσσ

σσσ

σσσ

and the new stress matrix is symmetric as expected.

(b) From Cauchy’s law, the traction vector is

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎣

⎡

−=

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎣

⎡

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎣

⎡

−

−=

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎣

⎡

2

1

2

1

2

1

2

1

)(

3

)(

2

)(

1 2

0

120

231

012

n

n

n

t

t

t

so that ( ) ( ) ( ) 321

)(

ˆ2/12/12 eeet n

+−= . The normal and shear stress on the

plane are

2/3)(

=⋅= nt n

Nσ

and

2/3)2/3(3 222)(

=−=−= NS σσ n

t

The normal to the plane is equal to 3e′ and so Nσ should be the same as 33σ ′ and it

is. The stress Sσ should be equal to ( ) ( )2

32

2

31 σσ ′+′ and it is. The results are

1x

1e 22 ee ′=

3e

3e′

22 xx ′=

3x

1e′

1x′

3x′

o

45

o

45](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/073delasticity023dstressstrain-170829112447/85/07-3-d_elasticity_02_3d_stressstrain-8-320.jpg)

![Section 7.2

Solid Mechanics Part II Kelly209

displayed in Fig. 7.2.9, in which the traction is represented in different ways, with

components ( ))(

3

)(

2

)(

1 ,, nnn

ttt and ( )333231 ,, σσσ ′′′ .

Figure 7.2.9: traction and stresses acting on a plane

Isotropic State of Stress

Suppose the state of stress in a body is

[ ]

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎣

⎡

==

0

0

0

0

00

00

00

σ

σ

σ

δσσ σijij (7.2.17)

One finds that the application of the stress tensor transformation rule yields the very same

components no matter what the new coordinate system{▲Problem 3}. In other words, no

shear stresses act, no matter what the orientation of the plane through the point. This is

termed an isotropic state of stress, or a spherical state of stress. One example of

isotropic stress is the stress arising in a fluid at rest, which cannot support shear stress, in

which case

[ ] [ ]Iσ p−= (7.2.18)

where the scalar p is the fluid hydrostatic pressure. For this reason, an isotropic state of

stress is also referred to as a hydrostatic state of stress.

7.2.4 Principal Stresses

For certain planes through a material particle, there are traction vectors which act normal

to the plane, as in Fig. 7.2.10. In this case the traction can be expressed as a scalar

multiple of the normal vector, nt n

σ=)(

.

3en ′=

22 xx ′=

1x′

2

3

33 =′=σσN

)(n

t

2

3

32 −=′σ

2

1

31 =′σ

2)(

1 =n

t

2

1)(

2 −=n

t

2

1)(

3 =n

t Sσ

1x](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/073delasticity023dstressstrain-170829112447/85/07-3-d_elasticity_02_3d_stressstrain-9-320.jpg)

![Section 7.2

Solid Mechanics Part II Kelly210

Figure 7.2.10: a purely normal traction vector

From Cauchy’s law then, for these planes,

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎣

⎡

=

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎣

⎡

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎣

⎡

==

3

2

1

3

2

1

333231

232221

131211

,,

n

n

n

n

n

n

nn ijij σ

σσσ

σσσ

σσσ

σσσ nnσ (7.2.19)

This is a standard eigenvalue problem from Linear Algebra: given a matrix [ ]ijσ , find

the eigenvalues σ and associated eigenvectors n such that Eqn. 7.2.19 holds.

To solve the problem, first re-write the equation in the form

( ) ( )

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎣

⎡

=

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎣

⎡

⎪

⎭

⎪

⎬

⎫

⎪

⎩

⎪

⎨

⎧

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎣

⎡

−

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎣

⎡

=−=−

0

0

0

100

010

001

,0,

3

2

1

333231

232221

131211

n

n

n

njijij σ

σσσ

σσσ

σσσ

σδσσ 0nIσ (7.2.20)

or

⎥

⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢

⎢

⎣

⎡

=

⎥

⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢

⎢

⎣

⎡

⎥

⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢

⎢

⎣

⎡

−

−

−

0

0

0

3

2

1

333231

232221

131211

n

n

n

σσσσ

σσσσ

σσσσ

(7.2.21)

This is a set of three homogeneous equations in three unknowns (if one treats σ as

known). From basic linear algebra, this system has a solution (apart from 0=in ) if and

only if the determinant of the coefficient matrix is zero, i.e. if

0det)det(

333231

232221

131211

=

⎥

⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢

⎢

⎣

⎡

−

−

−

=−

σσσσ

σσσσ

σσσσ

σIσ (7.2.22)

Evaluating the determinant, one has the following cubic characteristic equation of the

stress tensor σ ,

032

2

1

3

=−+− III σσσ Characteristic Equation (7.2.23)

and the principal scalar invariants of the stress tensor are

no shear stress – only a normal

component to the traction

n

nt n

σ=)(](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/073delasticity023dstressstrain-170829112447/85/07-3-d_elasticity_02_3d_stressstrain-10-320.jpg)

![Section 7.2

Solid Mechanics Part II Kelly212

Example

The stress at a point is given with respect to the axes 321 xxOx by the values

[ ]

⎥

⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢

⎢

⎣

⎡

−

−−=

1120

1260

005

ijσ .

Determine (a) the principal values, (b) the principal directions (and sketch them).

Solution:

(a)

The principal values are the solution to the characteristic equation

0)15)(5)(10(

1120

1260

005

=+−+−=

−−

−−−

−

σσσ

σ

σ

σ

which yields the three principal values 15,5,10 321 −=== σσσ .

(b)

The eigenvectors are now obtained from Eqn. 7.2.25. First, for 101 =σ ,

09120

012160

0005

321

321

321

=−−

=−−

=++−

nnn

nnn

nnn

and using also the equation 12

3

2

2

2

1 =++ nnn leads to 321 )5/4()5/3( een +−= . Similarly,

for 52 =σ and 153 −=σ , one has, respectively,

04120

012110

0000

321

321

321

=−−

=−−

=++

nnn

nnn

nnn

and

016120

01290

00020

321

321

321

=+−

=−+

=++

nnn

nnn

nnn

which yield 12 en = and 323 )5/3()5/4( een += . The principal directions are sketched in

Fig. 7.2.12. Note that the three components of each principal direction, 321 ,, nnn , are the

direction cosines: the cosines of the angles between that principal direction and the three

coordinate axes. For example, for 1σ with 5/4,5/3,0 321 =−== nnn , the angles made

with the coordinate axes 321 ,, xxx are, respectively, 0, 127o

and 37o

.

Figure 7.2.12: principal directions

■

3x

1x

2x

3

ˆn1

ˆn

2

ˆn

o

37](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/073delasticity023dstressstrain-170829112447/85/07-3-d_elasticity_02_3d_stressstrain-12-320.jpg)

![Section 7.2

Solid Mechanics Part II Kelly213

Invariants

The principal stresses 321 ,, σσσ are independent of any coordinate system; the 3210 xxx

axes to which the stress matrix in Eqn. 7.2.19 is referred can have any orientation – the

same principal stresses will be found from the eigenvalue analysis. This is expressed by

using the symbolic notation for the problem: nnσ σ= , which is independent of any

coordinate system. Thus the principal stresses are intrinsic properties of the stress state at

a point. It follows that the functions 321 ,, III in the characteristic equation Eqn. 7.2.23

are also independent of any coordinate system, and hence the name principal scalar

invariants (or simply invariants) of the stress.

The stress invariants can also be written neatly in terms of the principal stresses:

3213

1332212

3211

σσσ

σσσσσσ

σσσ

=

++=

++=

I

I

I

(7.2.26)

Also, if one chooses a coordinate system to coincide with the principal directions, Fig.

7.2.12, the stress matrix takes the simple form

[ ]

⎥

⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢

⎢

⎣

⎡

=

3

2

1

00

00

00

σ

σ

σ

σij (7.2.27)

Note that when two of the principal stresses are equal, one of the principal directions will

be unique, but the other two will be arbitrary – one can choose any two principal

directions in the plane perpendicular to the uniquely determined direction, so that the

three form an orthonormal set. This stress state is called axi-symmetric. When all three

principal stresses are equal, one has an isotropic state of stress, and all directions are

principal directions – the stress matrix has the form 7.2.27 no matter what orientation the

planes through the point.

Example

The two stress matrices from the Example of §7.2.3, describing the stress state at a point

with respect to different coordinate systems, are

[ ]

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎣

⎡

−

−=

120

231

012

ijσ , [ ]

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎣

⎡

−

−=′

2/32/12/1

2/132/3

2/12/32/3

ijσ

The first invariant is the sum of the normal stresses, the diagonal terms, and is the same

for both as expected:

63132 2

3

2

3

1 =++=++=I

The other invariants can also be obtained from either matrix, and are

3,6 32 −== II

■](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/073delasticity023dstressstrain-170829112447/85/07-3-d_elasticity_02_3d_stressstrain-13-320.jpg)

![Section 7.2

Solid Mechanics Part II Kelly215

Shear Stresses

Next, it will be shown that the maximum shearing stresses at a point act on planes

oriented at 45o

to the principal planes and that they have magnitude equal to half the

difference between the principal stresses. First, again, let 321 ,, eee be unit vectors in the

principal directions and consider an arbitrary unit normal vector iin en = . The normal

stress is given by Eqn. 7.2.29,

2

33

2

22

2

11 nnnN σσσσ ++= (7.2.32)

Cauchy’s law gives the components of the traction vector as

⎥

⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢

⎢

⎣

⎡

=

⎥

⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢

⎢

⎣

⎡

⎥

⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢

⎢

⎣

⎡

=

⎥

⎥

⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢

⎢

⎢

⎣

⎡

33

22

11

3

2

1

3

2

1

)(

1

)(

1

)(

1

00

00

00

n

n

n

n

n

n

t

t

t

σ

σ

σ

σ

σ

σ

n

n

n

(7.2.33)

and so the shear stress on the plane is, from Eqn. 7.2.11,

( ) ( )22

33

2

22

2

11

2

3

2

3

2

2

2

2

2

1

2

1

2

nnnnnnS σσσσσσσ ++−++= (7.2.34)

Using the condition 12

3

2

2

2

1 =++ nnn to eliminate 3n leads to

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ]2

3

2

232

2

131

2

3

2

2

2

3

2

2

2

1

2

3

2

1

2

σσσσσσσσσσσ +−+−−+−+−= nnnnS (7.2.35)

The stationary points are now obtained by equating the partial derivatives with respect to

the two variables 1n and 2n to zero:

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ]{ }

( ) ( ) ( ) ( )[ ]{ } 02

02

2

232

2

13132322

2

2

2

232

2

13131311

1

2

=−+−−−−=

∂

∂

=−+−−−−=

∂

∂

nnn

n

nnn

n

S

S

σσσσσσσσ

σ

σσσσσσσσ

σ

(7.2.36)

One sees immediately that 021 == nn (so that 13 ±=n ) is a solution; this is the principal

direction 3e and the shear stress is by definition zero on the plane with this normal. In

this calculation, the component 3n was eliminated and 2

Sσ was treated as a function of the

variables ),( 21 nn . Similarly, 1n can be eliminated with ),( 32 nn treated as the variables,

leading to the solution 1en = , and 2n can be eliminated with ),( 31 nn treated as the

variables, leading to the solution 2en = . Thus these solutions lead to the minimum shear

stress value 02

=Sσ .

A second solution to Eqn. 7.2.36 can be seen to be 2/1,0 21 ±== nn (so that

2/13 ±=n ) with corresponding shear stress values ( )2

324

12

σσσ −=S . Two other](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/073delasticity023dstressstrain-170829112447/85/07-3-d_elasticity_02_3d_stressstrain-15-320.jpg)

![Section 7.2

Solid Mechanics Part II Kelly216

solutions can be obtained as described earlier, by eliminating 1n and by eliminating 2n .

The full solution is listed below, and these are evidently the maximum (absolute value of

the) shear stresses acting at a point:

21

13

32

2

1

,0,

2

1

,

2

1

2

1

,

2

1

,0,

2

1

2

1

,

2

1

,

2

1

,0

σσσ

σσσ

σσσ

−=⎟

⎠

⎞

⎜

⎝

⎛

±±=

−=⎟

⎠

⎞

⎜

⎝

⎛

±±=

−=⎟

⎠

⎞

⎜

⎝

⎛

±±=

S

S

S

n

n

n

(7.2.37)

Taking 321 σσσ ≥≥ , the maximum shear stress at a point is

( )31max

2

1

σστ −= (7.2.38)

and acts on a plane with normal oriented at 45o

to the 1 and 3 principal directions. This is

illustrated in Fig. 7.2.14.

Figure 7.2.14: maximum shear stress at a point

Example

Consider the stress state examined in the Example of §7.2.4:

[ ]

⎥

⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢

⎢

⎣

⎡

−

−−=

1120

1260

005

ijσ

The principal stresses were found to be 15,5,10 321 −=== σσσ and so the maximum

shear stress is

( )

2

25

2

1

31max =−= σστ

One of the planes upon which they act is shown in Fig. 7.2.15 (see Fig. 7.2.12)

1

3

maxτ

maxτ

principal

directions](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/073delasticity023dstressstrain-170829112447/85/07-3-d_elasticity_02_3d_stressstrain-16-320.jpg)

![Section 7.2

Solid Mechanics Part II Kelly217

Figure 7.2.15: maximum shear stress

■

7.2.6 Mohr’s Circles of Stress

The Mohr’s circle for 2D stress states was discussed in Part I, §3.5.4. For the 3D case,

following on from section 7.2.5, one has the conditions

12

3

2

2

2

1

2

3

2

3

2

2

2

2

2

1

2

1

22

2

33

2

22

2

11

=++

++=+

++=

nnn

nnn

nnn

NS

N

σσσσσ

σσσσ

(7.2.39)

Solving these equations gives

( )( )

( )( )

( )( )

( )( )

( )( )

( )( )2313

2

212

3

1232

2

132

2

3121

2

322

1

σσσσ

σσσσσ

σσσσ

σσσσσ

σσσσ

σσσσσ

−−

+−−

=

−−

+−−

=

−−

+−−

=

SNN

SNN

SNN

n

n

n

(7.2.40)

Taking 321 σσσ ≥≥ , and noting that the squares of the normal components must be

positive, one has that

( )( )

( )( )

( )( ) 0

0

0

2

21

2

13

2

32

≥+−−

≤+−−

≥+−−

SNN

SNN

SNN

σσσσσ

σσσσσ

σσσσσ

(7.2.41)

and these can be re-written as

( )[ ] ( )[ ]

( )[ ] ( )[ ]

( )[ ] ( )[ ]2

212

12

212

12

2

312

12

312

12

2

322

12

322

12

σσσσσσ

σσσσσσ

σσσσσσ

−≥+−+

−≤+−+

−≥+−+

NS

NS

NS

(7.2.42)

3x

1x

2x

3

ˆn1

ˆn

2

ˆn

o

37

maxτ](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/073delasticity023dstressstrain-170829112447/85/07-3-d_elasticity_02_3d_stressstrain-17-320.jpg)

![Section 7.2

Solid Mechanics Part II Kelly218

If one takes coordinates ( )SN σσ , , the equality signs here represent circles in ( )SN σσ ,

stress space, Fig. 7.2.16. Each point ( )SN σσ , in this stress space represents the stress on

a particular plane through the material particle in question. Admissible ( )SN σσ , pairs are

given by the conditions Eqns. 7.2.42; they must lie inside a circle of centre ( )( )0,312

1

σσ +

and radius ( )312

1

σσ − . This is the large circle in Fig. 7.2.16. The points must lie outside

the circle with centre ( )( )0,322

1

σσ + and radius ( )322

1

σσ − and also outside the circle

with centre ( )( )0,212

1

σσ + and radius ( )212

1

σσ − ; these are the two smaller circles in the

figure. Thus the admissible points in stress space lie in the shaded region of Fig. 7.2.16.

Figure 7.2.16: admissible points in stress space

7.2.7 Three Dimensional Strain

The strain ijε , in symbolic form ε , is a tensor and as such it follows the same rules as for

the stress tensor. In particular, it follows the general tensor transformation rule 7.2.16; it

has principal values ε which satisfy the characteristic equation 7.2.23 and these include

the maximum and minimum normal strain at a point. There are three principal strain

invariants given by 7.2.24 or 7.2.26 and the maximum shear strain occurs on planes

oriented at 45o

to the principal directions.

7.2.8 Problems

1. The state of stress at a point with respect to a 3210 xxx coordinate system is given by

[ ]

⎥

⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢

⎢

⎣

⎡

−−

−=

212

101

212

ijσ

Use Cauchy’s law to determine the traction vector acting on a plane trough this

point whose unit normal is 3/)( 321 eeen ++= . What is the normal stress acting

on the plane? What is the shear stress acting on the plane?

2. The state of stress at a point with respect to a 3210 xxx coordinate system is given by

[ ]

⎥

⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢

⎢

⎣

⎡

−

=

202

013

231

ijσ

Nσ

Sσ

• ••

3σ 2σ 1σ](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/073delasticity023dstressstrain-170829112447/85/07-3-d_elasticity_02_3d_stressstrain-18-320.jpg)

![Section 7.2

Solid Mechanics Part II Kelly219

What are the stress components with respect to axes 3210 xxx ′′′ which are obtained

from the first by a o

45 rotation (positive counterclockwise) about the 3x axis

3. Show, in both the index and matrix notation, that the components of an isotropic

stress state remain unchanged under a coordinate transformation.

4. Consider a two-dimensional problem. The stress transformation formulae are then,

in full,

⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢

⎣

⎡ −

⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢

⎣

⎡

⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢

⎣

⎡

−

=⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢

⎣

⎡

′′

′′

θθ

θθ

σσ

σσ

θθ

θθ

σσ

σσ

cossin

sincos

cossin

sincos

2221

1211

2221

1211

Multiply the right hand side out and use the fact that the stress tensor is symmetric

( 2112 σσ = - not true for all tensors). What do you get? Look familiar?

5. The state of stress at a point with respect to a 3210 xxx coordinate system is given by

[ ]

⎥

⎥

⎦

⎤

⎢

⎢

⎣

⎡

−

−

=

100

02/52/1

02/12/5

ijσ

Evaluate the principal stresses and the principal directions. What is the maximum

shear stress acting at the point?](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/073delasticity023dstressstrain-170829112447/85/07-3-d_elasticity_02_3d_stressstrain-19-320.jpg)