Saint-Nazaire visit book

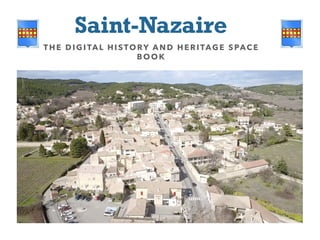

- 1. Saint-Nazaire THE DI GITAL HISTORY AND HE RITAGE SPACE BOO K

- 2. Traces of human occupation dating back to the Neolithic period have been found in Saint-Nazaire, including a magnificent axe found within the commune. The archaeological record is even richer for the gallo-roman period, including the vestiges of a nymphaea found in the basement of the presbytery; this suggests that the medieval church was built on top of an ancient site. Thus, the village of Saint-Nazaire may be one of the oldest settlements in the Gard. It is located on the roman Via Alba, the road to Alba, the Helvian capital; formerly known as Aps, the town, in the Ardèche region, now carries the name of Alba la Romaine for cultural and tourist marketing reasons. The settlement at Saint-Nazaire benefitted from the traffic on this major road, and from cultivation of the surrounding plains, drained and enhanced by the gallo-romans. The local landscape has been shaped by human activity over millennia, something which we often forget. By the thirteenth Century, the already well-established village is set in the heart of a territory developed over centuries by its former inhabitants. Whilst the rich vineyard landscape of the plains was largely moulded by the Romans, masters in the art of territorial development, the open fields on the slopes date from the medieval period. This space was brought under cultivation in response to demographic changes. The plains around Saint-Nazaire were drained, in ancient times, by the inhabitants of a few villages; by the Middle Ages, more agricultural land was needed to feed the town’s growing population of 150 – 250 individuals. The hillside, previously used to pasture sheep, was given over to more intensive cultivation, as were the valley bottoms, where rich earth had built up over time. Artificial terraces were entirely created by moving large quantities of earth, a practice which continued up until the mid-19th Century. General history of Saint-Nazaire DR MICHAEL PALATAN & PAULINE COLLUS (T R AD. )

- 3. The origins of the village itself are uncertain – a common problem for historians; it is very rare to be able to give a specific date for the foundation of a settlement. The presence of the manor house indicates that there was a village on this site during the Middle Ages, although little else is known about the medieval village; it may have been built as part of the medieval fort complex, or as a completely new settlement, as in the case of Saint-Laurent la Vernède, where a fortified village was rebuilt next to an older village, reusing some of the original materials. The village fort was created during the second half of the 14th Century, as in many other villages in the area and along both banks of the Rhône. Traces of this can be seen in the street plan, and the base of one of the four round towers set into the walls is still visible on old photographs. After the Hundred Years’ War and the plague epidemics of the 14th and 15th Centuries came the Wars of Religion. The population of Saint-Nazaire clearly recognised the need for protection and the value of solid ramparts. The village was subject to further difficulties in the 17th Century, with increased fiscal pressures; a four-fold rise in taxes during the first half of the century resulted in a number of peasant revolts, which were put down by force. However, the economy of Saint-Nazaire continued to profit from the village’s advantageous position alongside a busy road, as we see from the existence of a hostelry in the village over the course of the 17th Century – despite the fact that much of the traffic towards Marseille or Beaucaire was waterborne, travelling down the Rhône.

- 4. Following the climatic disasters of the late 17th and early 18th Centuries – notably the Great Winter of 1709, which was particularly harsh all over Europe – the second half of the 18th Century saw an increase in the population of Saint-Nazaire, stimulated by improvements to the road and by economic development. This trend continued until the middle of the next century, with the emergence of heavy industry and the building of railways in the region. Saint-Nazaire was not immune to the rural exodus phenomenon, which affected every village in the country to a greater or lesser extent from the 1860s onwards. The lowest population levels were reached in 1926, at which point the inhabitants of France were split equally between urban and rural settlements. The first five-year plan for nuclear investment, launched in 1951 by Secretary of State Félix Gaillard, led to the construction of a plutonium production site at Marcoule, in the vicinity of Saint-Nazaire, in 1956. The population of the village tripled in the space of a few years, reaching 900 in 1956. Saint- Nazaire took on a more modern aspect, whilst retaining its vineyards and its essentially rural character. Whilst the busy road – a royal, imperial then National thoroughfare – detracts somewhat from the peace of the commune, the construction of a bypass should resolve the issue, marking the start of a new era for Saint-Nazaire, its destiny shaped by its inhabitants.

- 5. Saint-Nazaire has retained its medieval manor house, in spite of multiple renovation and remodelling phases over the centuries. The manor house is a fortified dwelling, designed to protect its inhabitants from attack by brigands or thieves. The house does not appear to have been built following the castle model, and was thus never intended to provide protection for the whole village; this role was fulfilled by the fort, constructed in the late 14th Century. As in Poët-Laval in the Drôme region, or in the neighbouring village of Cavillargues, the manor house is integrated into the village walls; the same was often true of churches. This strategy enabled the creation of strong fortifications at a reduced cost, killing two birds with one stone; a good example can be seen at Saint-Hilaire d’Ozilhan. The north side of the building features two different types of blockwork, featuring small blocks of dressed stone (larger blocks were also used in the region at the time, as at the Pont-du-Gard) for the lower ¾ of the building. The top quarter of the north side features more crudely-cut blocks. This clearly indicates two distinct phases of construction, which can be dated on the basis of the techniques used for the windows on each level, along with the use of rough-cut moellons. The presence of a segmented arch in one of the lintels indicates that the top section was added during the 18th or 19th Century – perhaps as a granary, an additional floor, or even as a silkworm nursery, with the aim of profiting from the spectacular rise of the silk industry in the mid-18th Century. At some point, this upper section was used as a pigeon loft. Examining both sides of the building, we see that the upward extension is not of the same height on the two façades, resulting in a 180° shift in the dominant orientation. The main façade of the fortified dwelling faced inward, towards the village, but the elevation of the north side over the south side changed this. The lateral wall, originally located to the north, thus became part of the south façade. This reorientation of the building, along with the likely creation of a garden or courtyard to the front, is symptomatic of a greater sense of security and of the diminishing importance of defensive architecture in the 19th Century, even maybe late 19th Century. 1 The manor house MIC HAEL PALATAN & PAULINE COLLUS (TRAD. )

- 6. Looking closely at the façades, we note the presence of rusticated stonework, where blocks are cut in a way which leaves a rough, unfinished area on the front. This style of masonry is common in the Gard area. Imported from the Middle East by the Crusaders, along with a number of other fortification techniques, it was notably used by the Kings of France’s architects at Aigues-Mortes, along with other oriental innovations; this had a considerable impact on building practices across the region. In defensive terms, rusticated stonework increases the resistance of walls to stone projectiles. At the manor house in Saint-Nazaire, we see that rusticated blocks are only used sporadically, suggesting that the defensive element of this style of stonework was of secondary importance in this case. Its use seems to have been governed more by fashion, showing loyalty to the King, and may have been intended to give a more prestigious, regal air to the building by copying royal building styles. As the sociologist Nobert Elias indicates, fashions spread through societies from the top down, following examples set by the elite. The use of rusticated stonework in the manor house is a typical instance of this phenomenon. The presence of rusticated stonework also helps us to date the construction of the original edifice. Jean Mesqui, specialist in the medieval architecture of the Midi, places the appearance of rusticated stonework at the end of the 12th Century. Frédéric Salle-Lagarde proposes a slightly later date, which we find more convincing; according to this theory, the edifice was probably constructed at the start of the 13th Century. The fortified manor house was, in many ways, a successor to the feudal keep; cheaper to build, it also fulfilled different roles, and was generally occupied by representatives of the actual authorities. Fortified manor houses can be found across the Gard, including one at Allègre-les-Fumades which features a heraldic shield at the top of the edifice.

- 7. At this point, let us take a few minutes to discover an urban landscape of a bygone age: the barry. Barry is an Occitan term which originally designated the city walls, and came, by association, to denote the streets around the walls, both inside and, more often, outside the ramparts. In certain villages, the barry became a popular location for an evening stroll. The term barry forms the root of the French verb baruler: to stroll, but also to turn around in circles, aimlessly. Join us as we “barule” in virtual reality, taking a turn around the village outside of the walls; a 3D reconstruction has been created to give a clearer picture of this unique space. The distinct nature of the barry comes from its proximity to the village: the fields nearest the settlement were the most prestigious, the most productive, and the most valuable. This is due to the fact that they received the greatest quantity of manure, benefitting from proximity to the stables in the village; their location also meant that they were under constant surveillance. The fields nearest the village were thus used for specific types of production, different to those encountered in the surrounding countryside. First, closest to the walls – and in some places, up against them - we find kitchen gardens and alfalfa fields, followed by fields of high-yielding cereal crops. We know that the fields where the most manure was spread could produce up to five times more grain, with a harvest ratio of 15 harvested seeds to 1 sowed, compared to 1 harvested to 3 or 4 sowed in a good year for other fields. This highly-fertilised land was agricultural gold. As the kitchen gardens around Saint- Nazaire were also walled, there was a high density of dry-stone wall around the village. Some of the garden walls were up to two metres high, surrounded by 2 The Barry MIC HAEL PALATAN & PAULINE COLLUS (TRAD. )

- 8. brambles intended to dissuade climbing. The gardens were of critical importance in feeding the village population. Cultivated all year round, these highly-productive plots received the best possible fertiliser, in the form of chicken manure. In winter, they provided a supply of brassicas, which, together with bacon, tided the villagers over during the hungry gap; these were identified as cauli-fiori by Olivier de Serres in 1600. Up until the 19th Century, when famine ceased to be a regular o c c u r r e n c e , h u n g e r , a n d consequently the food supply, was a constant preoccupation. This can be seen from the height of the protective walls around the gardens. The villagers also needed to feed their livestock: horses (rare), oxen (few, and limited to the bigger smallholdings outside the village, for example at Le Brusquet), donkeys (many, generally ridden by women in the region, as noted by Jean Racine, who spent a few months nearby at Uzès), mules (many, used for agricultural purposes, notably drawing the plough), and sheep, with a flock of around 300 animals. varied over the years, with repeated outbreaks of disease decimating the population. Strolling around the outside of the village walls in our chosen year of 1631, we also come across fields of alfalfa. Alfalfa is an

- 9. excellent hay crop, and the harvest was destined for the hostelry to feed visitors’ horses. At this time, the two alfalfa fields and the hostelry belonged to the wealthiest of the local farmers, one Jean Coste esq., bailiff, the son of Barthélémy Coste who had also served as bailiff, like his father and forefathers before him. Near the village there also stands a single mulberry tree, almost certainly a relic of an abortive foray into the silk industry by the ancestors of Jacques Fabre, whose house lies outside the enclosure. A few other buildings can also be found outside the walls. These include the Coste house, inhabited by the family of bailiffs mentioned above; although they had the right to inhabit the manor house, dwelling outside of the village was a sign of social dominance. In this way, the family, representatives of the Count of Grignan, one of the region’s most powerful magnates, were able to mark their status. Their farm might have looked something like this, closed in on itself, with, as we see from the registers, a stable, a hay loft, a courtyard and an ubize, a type of shelter. Finally, the hostelry was situated along the road, with, according to the same registers, a pathway right around the building.

- 10. The location of Saint-Nazaire may well have been partly determined by the situation of an ancient site on the edge of the road – for example a cemetery. The gallo-romans built their cemeteries outside of the cities, along the edges of roads, and sometimes at a considerable distance from settlements. The dead were, effectively, expelled from the realm of the living. The construction of the village at Saint-Nazaire at an unknown date during the Middle Ages marked the reintegration of the cemetery into the settlement. During this period, the notion of connection between the living and the dead was strong; for example, Masses were said for the souls of the departed, providing a constant reminder of their presence. Through the church, the dead benefitted from a form of continued existence, even before the bodily resurrection which was expected to occur at the end of time. This revolution in the approach to death can be seen through archive documents. The cadastral plan shows the cemetery at the heart of the old village, the fort. It does not appear in the 1631 registers, but its presence can be deduced from an inventory of feudal dues, in which several houses – no longer in existence – are described as backing on to the cemetery on their south side. One house was almost entirely surrounded by the cemetery, which may have looked something like this. Following medieval and early modern usages, we would expect to find a cross at the centre of the site. Villagers were buried simply, and only the very richest lay or clerical magnates had tombstones. Members of these elites were generally buried in the nave of the church, with proximity to the altar determined by rank; the area nearest the altar was considered to be the most sacred. The lords who exercised power over Saint- 3 The cemetery MIC HAEL PALATAN & PAULINE COLLUS (TRAD. )

- 11. Nazaire were buried in more prestigious chapels at Caderousse or Grignan. Mere villagers, however, could only expect to be buried in the cemetery, without the added aura of sanctity conferred by the church buildings. A number of strategies were used in an attempt to reach heaven as quickly as possible, or to reduce one’s time in purgatory. Preferred locations included the area around the central cross, or plots as close as possible to the church walls. The right to be buried in these locations was conferred by the priest, and the inhabitants might have attempted to curry favour by offering financial support. Particularly pious individuals might request the right to be buried at the entrance to the church, where they would be constantly trampled by churchgoers, in a show of profound humility. Death was a continual concern and the subject of numerous and complex fantasies, which rendered it less opaque than in modern times, where cremation, rather than burial, is becoming the norm. In many cases, our communities have followed the Roman pattern, building cemeteries outside of settlements – although, in some cases, the settlements have then extended out towards the cemeteries. This new wave of expulsion of the dead originated in the late 18th Century with a change in sensibilities: the putrid odours of the cemetery and the sight of bones dug up by dogs were no longer welcome within the village, and inhabitants preferred not to have their boules games disturbed by burials. Whilst the notion of playing petanque in a cemetery may seem bizarre by modern standards, the central location of burial grounds made them a prime meeting point for games, chat and even commerce, reflecting the pre-modern sense of continuity between life and death. In one neighbouring town, the Revelly brothers – about whom nothing else is known – were even condemned to eight days in prison for playing boules in a cemetery with freshly-exhumed skulls! LO REM I PSU M DOLOR

- 12. A lack of information makes it difficult to create a reconstruction of the fortified village as it was towards the end of the 14th Century, a walled edifice with watchtowers at each corner. So, we have no other choice than focusing on a more recent era, for which more documentation is available: the 17th Century, specifically the 1630s, using a register from 1631. This document, which is the subject of another mini-presentation, covers almost all of the developed and undeveloped parcels of land in Saint-Nazaire, with the exception of seigneurial and ecclesiastical holdings which were exempt from paying tax. The fortified manor house, the church and the associated buildings do not feature in the register; nor do communal buildings. A second document, a list of feudal dues held in the archives at Bagnols (ref. II 20), provides us with some of the information which is missing from the register. So here is the historian’s attempt. Firstly, note that the situation of built-up parcels is described in relation to other built-up areas; for example, one Master Jean Borie possessed, amongst other things, une maison et couvert attouchable, i.e. a house with an adjoining outbuilding, in Saint-Nazaire, confrontant du levant, i.e. touching, on the east; and a bise, i.e on the north side, a house belonging to Barthélémy Ligonnetz; to the west, du couchant, was the road, and so on. As the location of each house is described in relation to the others, we began by identifying a starting point for our reconstruction, taking a house with a known position – a building situated against the town walls appeared to be most suitable, 4 Reconstruction of a quarter in the 17th Century

- 13. allowing us to create a working document for the south east corner of the village, covering around ¼ of the surface of the 17th Century settlement. In our first diagram, the houses are represented by abstract blocks, situated in relation to one another following the details provided in the register. In this first stage of the reconstruction process, our aim was simply to establish relative positions and to obtain a coherent spatial configuration. In the second stage, our aim was to readjust our blocks to create a diagram which better reflected the multiple configurations described in the documents. The resulting diagram corresponded more closely to reality, and a comparison with the 19th Century cadastral plan showed a high level of similarity. Clearly, changes occurred during the intervening years: courtyards were used to build new houses, blocks of houses were split, and the village extended beyond the walls on the east side. One house, n° 25 on the cadastral plan and n° 37 on our diagram, belonging, according to the register, to one Claude Ligonnetz, appears to have remained untouched over the period from 1631, when the register was created, to 1824, date of the Napoleonic cadastral plan. This may well provide an indication of the orientation of the medieval walls. To the south, considerable changes seem to have been made, as a house belonging to Barthéméy Ligonnets touched the walls on both its eastern and southern sides. No mention is made of a corner tower; instead, there was a street, which shows that there was no tower in this location at that time. There was thus an opening in the wall at this point, resulting from the demolition of the tower. Whether the tower was destroyed during the Wars of Religion, or by the populace themselves who reused stone from the walls for construction elsewhere in the village, or even as a result of wear and tear with age, remains unknown. Further research may yet provide answers to these questions some day…

- 14. At first glance, looking at the façades of the houses, the village appears to follow a simple and perfectly ordered plan. But nothing could be further from the truth. Some of the houses in the village have evolved over centuries, developing highly complex configurations. Façades reveal little about what goes on behind them. Houses may overlap or intersect. They may conceal hidden courtyards which open onto other secret spaces, creating a whole urban landscape accessible only to the owners. There are cellars dug into the rock itself, from which stone was taken to build the houses. The village of Saint-Nazaire is built on rock, both from necessity and utility. Building on less solid bases requires the creation of foundations, a difficult and laborious process; in the Midi, builders often avoided the problem by building directly on the rock, using stone found on-site. Saint-Nazaire is a village of stone, effectively built into its own quarry. In the 14th Century, the villagers even succeeded in building a high wall around their settlement, over 5 metres high in some places. The challenge for subsequent generations was to make space within these walls for an expanding population; expansion outside the walls only really began in the 19th Century, with very few buildings located extramuros before this date. These included a hostelry, a yeoman farmer’s residence – almost certainly within its own enclosure – and one further house. The barns built to serve the outermost fields were inhabited only by day-labourers, tenants willing to accept the risks associated with living so far from the village. 5 The androne MIC HAEL PALATAN & PAULINE COLLUS (TRAD. )

- 15. The owners of these barns generally lived in the town. The villagers themselves preferred to live within the city walls, behind gates which were closed when night fell. They mistrusted the night, with the risk of incursion by bandits, chicken thieves, outcasts and other miscreants. Villagers only started building new houses outside of the walls in the 18th, or even the 19th Century, displaying a tendency widely encountered in the Languedoc and neighbouring reasons. The rotation of the manor house, now occupied by farmers, marked this change in attitude toward the outside. The same shift can be seen in the creation of openings in the walls, means by which still more houses changed their orientation to look outwards. Rather than following the inward-looking pattern of previous centuries, in the 19th Century, the villagers began to look outwards, towards the roads and paths around the village. More and more houses were built outside of the fortified enclosure, along the road and to the north; a second, more comfortable, more spacious village grew up alongside the existing settlement. Before this shift in mentality took place, however, all construction happened within the existing ramparts; no one was willing to accept the dangers associated with life outside the enclosure. In a space which had already reached saturation point by the end of the 14th Century, the only way to go was up. Thus, a form of rural “high rise” construction emerged, comparable to that encountered in the towns under similar constraints. However, multi-storey house building required a level of skill and investment rarely encountered in the village. Up until the 19th Century, the “standard” dwelling was on a single level, with an additional loft space used for grain or hay storage; two- storey buildings were the exception, rather than the rule. Extensions were created by the use of andrones, which reached across streets, solving the problem of space whilst avoiding the need to add storeys onto structures designed with a lower maximum height in mind. To extend upwards, the walls on the ground floor of the house need to be of a certain thickness, and in order to limit construction costs, the peasantry tended to limit this dimension to the bare minimum required for a specific roof height. In other terms, the walls were not designed to support additional storeys, and the inhabitants simply did not have the means to plan for this type of extension. The uncertainty inherent in agricultural production and a high dependency on climatic conditions meant that long-term planning was generally pointless. The androne, noted “chamber” in the

- 16. 1631 register – indicating its purpose as sleeping quarters – was one of the few means of extending a house on a limited budget. In 1631, the androne under which you are standing belonged to one Mathieu Ligonnetz, owner of the house to the west.

- 17. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, ligula suspendisse nulla pretium, rhoncus tempor. The origins of some buildings appear to be lost in the mists of time. The church of Saint-Nazaire is one of them. The oldest mention of the church dates back to a cadastral plan established in the first decades of the 19th Century. The building itself is small, but sufficiently large for the village population. It is oriented – i.e. turned toward the east – and features a circular apse. It only appears to have two bays. With its round apse, it may have looked something like this. The presbytery was built in the early 19th Century, marking the re- establishment of the Catholic Church as a force in the parish, following the tumultuous revolutionary period, during which the church building itself was damaged. Abbé Goiffon mentions significant building work taking place in around the 1850s; the church as we see it now, sandwiched between two other buildings, is the result of this transformation. In 1825, the church was bounded by the cemetery on the west side; this space was used for the later extension, with the aim of creating enough room for the village’s increasing population. A number of rituals and developments followed the restoration and extension of the church at Saint- Nazaire, including the nomination of a parish council, an inventory of church goods, and the installation of a bell, which was blessed on 21st November 1859. Local historian Gérard Pouly tells us more: cf: video https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gpXCCE9C314 (1’58 - 2’20) 6 The bells: MIC HAEL PALATAN & PAULINE COLLUS (TRAD. )

- 18. It is hard to overestimate the importance of bells for a village in the past. In Saint-Nazaire and elsewhere, the bell was a tool for communication, used by councillors a n d c l e r g y t o a d d r e s s t h e population. It was also a tool for synchronisation, marking different moments throughout the day, including the Angelus, recited three times each day. The knell sounded to mark a death, the tocsin to raise the alarm in case of imminent danger. The bells were also rung in an attempt to ward off storms, with the aim of diverting the thunder clouds towards Vénéjean, Saint-Alexandre or Saint-Gervais. This superstitious and profane use of the bells was not always appreciated by the clergy. The bell, and the “soundscape” of its regular ringing, formed an integral part of village life. Villagers felt affection for their bells, calling them by their names; in locations with multiple bells, the inhabitants could recognise each one. They were also ready to pay for the privilege, raising subscriptions to refound a bell which were damaged and had ceased to ring as they should. Populations grew up with “their” bells, and were familiar with the particular timbre of those of the village, distinct from those of other villages in the area, which were treated with condescension and real bad faith. The possession of a bell loud enough to be heard by the neighbours was a sign of power and

- 19. a source of great pride. During the Revolution, large numbers of bells were requisitioned to be melted down for canons, particularly in villages which had more than one. In some cases, warned of the arrival of the local revolutionary authorities, the inhabitants buried their bell to save it from its fate. In earlier times, the bells rang throughout the day. Now, they mark the hours, reminding us of their position at the heart of village life. Village spirit is referred to in French as campanilisme, from the Italian campanile, bell-tower: the bells were both the focus and the symbol of belonging.

- 20. In his statistical analysis of the Gard département, Hector Rivoire dismissed Saint- Nazaire as a village of little importance, with agricultural production which was limited and of poor quality. The only positive point he noted was the view from the Roquebrune because Rivoire’s analysis focused exclusively on economic production. However, at the time of his visit in 1842, Saint-Nazaire was a staging post on one of the kingdom’s most important roads: there was thus an important service sector built around catering for travellers. Before the arrival of the railways and the construction of the A7 motorway, which significantly reduced the prominence of the N86 at Saint-Nazaire, the road was of considerable importance, holding royal and even imperial status at one point in its history. The thoroughfare was sufficiently developed to withstand regular coach traffic travelling at a gallop. In the 18th Century, a vast network of high-quality roads was established, branching out from Paris to reach all four corners of the country; this was important for France’s economic development. At local level, this development was organised by the États du Languedoc from 1709, intensifying in the second half of the 18th Century. The wholesale reconstruction of the Great Post Road which passes Saint- Nazaire began in around 1730, and in 1748 the famed Henri Pitot, then director of works for the Sénéchaussée of Nîmes-Beaucaire, took reception of the section of road between Bagnols and Saint-Nazaire, including part of the notorious Roquebrune slopes. 7 A staging post on the Roquebrune MIC HAEL PALATAN & PAULINE COLLUS (TRAD. )

- 21. Very sensibly, the architect responsible for the road bridge doubling the Pont-du-Gard decided to wait out a whole winter to monitor the quality of the piling and the bridge’s resistance to bad weather. At the very end of the 18th Century, an English traveller, highly critical of the Kingdom of France in his travel journals, nonetheless noted that in Languedoc one found “truly marvellous roads”. It would seem that the great Roman road, the Narbonnaise, of which large stretches remained intact, had a part to play in the Languedocian tendency to build wide roads of impressive quality. The biggest road-building project ever seen in France was gradually put in place, assisted and observed by the inhabitants of Saint-Nazaire. Whilst the local populace participated in the project over the course of the 17th Century, this came to a halt after 1709 when the États de Languedoc decided to cease investing in road-building, farming out the work to the cheapest contractor. It may have been at this time that the course of the road was changed; where once it went round the village on the west side, it later skirted the east side of the village, as we see today. This change is described by Canon Beraud in his work on Saint-Nazaire, but unfortunately the author fails to date the event. The road thus played an important role in the life of Saint-Nazaire. The local economy reflected this, with the presence of services intended to serve road users. Over time, the village was home to woodworkers, innkeepers, merchants and blacksmiths, and also, more importantly, the hostelry, providing travellers with somewhere to sleep if they arrived after dark and too late to go on to Bagnols or Pont-Saint-Esprit. Visitors might also have cause to stop following mishaps on the road. Even the royal post roads were not lit after dark, and it was dangerous to travel after nightfall due to the risk of falling into a ditch, as happened to Voltaire on his way to visit the self-acclaimed philosopher king and poet, Frederick II, in Prussia. Proximity to Bagnols meant that few travellers were obliged to stop at Saint-Nazaire, although the village did receive visits from royalty, including Louis XIII on 15th July and 8th August 1629, and Louis XIV, still a child, a few years later. The village was therefore unable to profit fully from its advantageous position on the road, a route of both regional and national significance and one of strategic importance for the contemporary authorities.

- 22. This trend was further reinforced by the reconstruction of the Great Post Road in the 1740s. In 1720 and 1721, however, a blocus on the Rhône, intended to prevent a plague outbreak from spreading beyond Provence, greatly increased circulation on the road. River transport was forbidden, so passengers and goods from Lyon, the Vivarais or Auvergne took the Saint-Esprit south, obliging them to pass through Saint-Nazaire. The salt trade along the Rhône was brought to a standstill, and this valuable commodity had to be transported by coach. The quantities involved were colossal: a large part of the kingdom received its salt from the Midi. The increase in road traffic was such that practically the whole road between Lunel and Saint-Esprit was destroyed. These two years were a boon for the economy in Saint-

- 23. Saint-Nazaire almost certainly originated as an ancient roadside site, such as a cemetery, fanum or even temple; by the 17th Century, however, the picture would have been very different. A number of useful archive documents are available for this period, allowing historians to create a profile of the village, comparing it to other neighbouring settlements which did not enjoy this favourable roadside position. The 1631 register lists 36 houses, but those which were not subject to tax, including the manor house and the prior’s house, were omitted. There were thus around 40 houses, which corresponds to the number of houses situated within the fort on our early-19th Century cadastral plan. From this perspective, the urban landscape appears to have remained stable throughout this period. Whilst some individuals lived on the smallholdings outside the village, almost all of the population was housed within the ramparts during the first third of the 17th Century. Only one farm, two other houses and the hostelry were located outside the village walls. As the village gates were closed at nightfall, the hostelry needed to be outside the walls in order to avoid enclosure. The economy of Saint-Nazaire was based on agriculture, but also on proximity to the road: the number of artisans operating in the village was higher than average. Saint-Nazaire is set on a slope, the montée de Roquebrune, which was particularly treacherous in bad weather. The director of public works for the Nîmes-Beaucaire area paid particular attention to this zone during the reconstruction of the road, demonstrating the importance of the issue. 8 The village in the 17th, 18th and 19th Centuries

- 24. The few vehicles which attempted the ascent in poor weather had to be assisted by members of the local population. For a few liards or patas, a number of young (and not-so-young) men would help to extract coaches which became stuck. The construction of the great road, wide and well-paved, after 1760 reduced the need for brute force. Horse-drawn vehicles were able to pass at speed - 10km/h or even more – and no longer needed to stop at Saint-Nazaire. As at Sénas, where the inhabitants missed one of the daughters of Louis XV, the aristocratic “celebrities” of the time no longer stopped in Saint- Nazaire; the construction of leafy triumphal arches and roadside decorations to celebrate their passage may well have ceased at this point. Almost all activity relating to the road was recentered on the neighbouring towns of Bagnols or Saint-Esprit. Nonetheless, Saint-Nazaire continued to grow; the surface area of the village doubled and the number of houses almost tripled between 1631 and 1881. This expansion is most probably due to slow but steady economic growth, in spite of the various issues which emerged and disasters which occurred towards the end of the 17th Century and around the beginning of the 18th Century. This upward trend accelerated during the 19th Century. The population multiplied, and the means of subsistence increased in parallel. Thanks to the interlinked economic and demographic explosions at this time, following the Revolution, France was able to rely on general mobilisation and conscription to defend its dreams of republic against the combined forces of the European monarchies, determined to re-establish a member of the House of Bourbon on the throne. This new, young population needed to live somewhere, and the village expanded beyond the walls of the fort. Surplus to requirements in an agrarian economy, more resistant to disease, the new generation provided Napoleon with forces to mobilise against enemies within and outside of the Empire, following the example seen in the revolutionary period. France’s dominance extended across Europe, spreading republican and Enlightenment ideals – but at the expense of hundreds of millions of lives. Today’s younger generation, faced with similar issues, will hopefully find the means of showing the world what they are capable of via new technologies, rather than through war and conquest.

- 25. In his History of Saint-Nazaire, Abbé Béraud speaks of a fort built by the villagers in the course of the 14th Century, following a trend found in the Midi and elsewhere: at the end of each summer’s campaigning season – the Hundred Years’ War was being waged at this time – bands of mercenaries would emerge under different captains, making their living through pillage and ransoms. Fortifications sprang up around all but the smallest villages as a reaction to this. Weakened by the plague of 1348, which degenerated into a pandemic, these small settlements were soon abandoned as their inhabitants sought refuge elsewhere. A considerable number of hamlets and even villages were deserted during the second half of the 14th Century; populations convened on locations where they would be protected by high defensive walls. The spatial organisation of the habitat underwent a process of military rationalisation at this time. Set on the edge of a road, Saint-Nazaire was located in a strategically important position, making fortification important. People gradually began to build outside the village again at the end of the 15th Century; later, large smallholdings would spring up in this outlying area, following the end of the Wars of Religion. This is discussed in greater detail elsewhere on our way. Saint-Nazaire might have disappeared, due to its proximity to the larger community at Bagnols, but continued to thrive and attracted the interest of contemporary elites; fortifications were thus established around the village. 9 Finding the village fort: the historian’s approach

- 26. Looking at the early 19th Century cadastral plan, we find traces of a square medieval fort, “fossilised” in the layout of the medieval walls and streets. During this period, forts generally took this shape, and were often constructed ex nihilo for this reason. In other terms, the fort which existed here probably looked like those at Saint- Laurent-la-Vernède or Cavillargues: a quadrangular space with four corner towers, built from scratch alongside the existing village. These structures could also be built around an existing settlement, in which case any buildings with the misfortune to lie on the site of the planned construction were simply demolished. Little or nothing remains of the square fort or of its watch towers at Saint- Nazaire, but its shape can be seen from existing plans; a rounded shape is also visible on an old picture postcard. Looking closely at the wall of a house adjoining the manor house, we find a level of regularity indicating that it was formerly part of the ramparts, providing evidence of a walkway along the walls. To create a walkway of this type, highly valuable for surveillance and offering a prime position for defensive action, ramparts were built up to a certain height, then large stone bars were placed crosswise to create a walkway. The wall was then built up further above the walkway, but with a reduced thickness to leave the walkway free. Major transformations around the medieval fort seem to have affected its original, attractive geometry. Once again, responsibility for these changes can be pinned on the road. Once again, we note the intimate connection between Saint-Nazaire and the road: the village could not exist without the highway, and in case of conflict between the two, the road always triumphed. Two structures are apparent: the fortified 14th Century village, which we see here, and transformations resulting from more recent reconstruction work in the 18th and 19th Centuries, which modified its orientation, following the main axis of the new road, increasingly influential after 1750 with the construction of the great royal highway. Work to straighten the road after 1748 during the reconstruction of the great highway, under the direction of the États-du- Languedoc, indirectly remodelled the parcel structure of the land along the road, generating a new web of paths which, over time, had a subtle effect on reorienting new buildings. As walls were built perpendicular to each other, a whole part of the village was constructed following the new orientation.

- 27. Medieval villages were under the control of local lords, whose dominance was more or less strongly felt according to the balance of power between magnate and subjects. Two complementary documents help us to understand the situation in Saint-Nazaire in the late 16th and early 17th Centuries. The first is a list of feudal dues conserved in the archives at Bagnols-sur-Cèze under the code II20. The second is a statement of fealty to the King by the Dame d’Ancézune, Lady of Caderousse, Vénéjean, Saint-Nazaire and other holdings. We see that on the thirteenth day of September in the year 1600, two envoys, Antoine Malarte and Laurens Borie arrived at the house of Master Barthélémy Coste, followed by a group of councillors. This was a solemn occasion: each villager was required to come to the house to declare fealty for the property they held of the lord of the manner. The Bailiff began by summoning the village authorities in order to set out the rights accorded to them by their overlord and to list their obligations. The previous form of the document seen here appears to date from 1388. From this original text, we see that the Count of Grignan held the whole of the village, as all of the rights came to him on his marriage to Jeanne Daucezune The documents provide a good illustration of the lord-vassal relationship. First the envoys, in their own name, then the villagers and their heirs, declared fealty to the Count of Grignan as “their true, legitimate and natural lord in the said village of Saint-Nazaire”, and agreed to submit to justice meted out by a judge operating within an ordinary court, made up of a legal procurator, a clerk and one or more ordinary sergeants; these courts were the first port of call for both civil and criminal cases. 10 Feudal customs MIC HAEL PALATAN & PAULINE COLLUS (TRAD. )

- 28. This judicial system operated at a very local level, and was a source of revenues for the lord, allowing them to pay a certain number of administrative staff (judges, procurators, fiscal clerks, bailiffs, etc.). The lord’s agents were also the only authorities able to guarantee the validity of commercial weights and measures. We learn that all uncultivated areas, all discovered or undiscovered mines, and all quarries belonged to the lord, who could use them as he saw fit. The lord also levied a tax on property transfers, les lods et ventes, worth one sixth of the value of any property sold or exchanged. The limited activity of the property market in these traditional societies is not surprising. To avoid taxes, transactions were usually conducted orally and guaranteed by the inhabitants of the village, taken as witnesses. Next, the document states that the populace owed an annual and perpetual quit-rent on all of their possessions – a form of annual property duty. In Saint-Nazaire, the population managed to buy back the rights to their quit-rents for the sum of six pounds in silver, two saumées of mixed grain land (just above one hectare) and twenty chickens. This administrative simplification almost certainly reduced the cost of the tax. More prosaically, the document stipulates that the tongues of all animals killed in the village were to be given to the lord. Hunting was forbidden without the authorisation of the lord of the manor, who permitted collective hunts for the purposes of exterminating vermin, what we call today beats. The villagers did not have the right to assemble without a licence from the lord or his representatives – a stipulation intended to control the size of crowds and to prevent revolts. The communal oven used by the inhabitants belonged to the lord, but we learn that the villagers had obtained the right to manage it themselves for a payment of 5 sols per year. The pulverage tax also went to the lord: this was a due paid by shepherds passing through the settlement in compensation for the dust stirred up by livestock, which then settled on the villagers’ produce. This shows that the great post road was also used for transhumance. The village commons included a hermas (unoccupied land) of two saumées, just over one hectare – probably a dry field where livestock used for ploughing (i.e. mules) could be put out to pasture, and which was cultivated in rotation. For this common land, the villagers owed “3 poules bonnes et compétentes” (3 good and skilful hens) – presumably young and good layers!