The document outlines the principles of Reliability-Centered Maintenance (RCM) and its applications in developing efficient maintenance programs for complex equipment, specifically within military contexts. It details the rationale for maintenance tasks, the systematic decision-making processes involved, and the importance of a collaborative approach between design and maintenance teams. Additionally, it discusses various maintenance tasks, evaluation criteria, and the necessary management information systems to sustain ongoing programs.

![nlent published under the title Handbook: Maintetranee Eval~rationand

lJro~ram Dtlvelopmenf,generally known as MSG-I.* MSG1 was used by

special teams of industry and FAA yersor~nel develop the initial pro-

to

grain issued by the FAA Maintenance Review Board for the Boeing 747.

As described by the FAA, these t e a s s t

. . . sorted out the potentid maintenance tasks and then evaluated

them to determine which must be done for operating safel.y or

essential hidden function protection. The remaining potential tasks

were evaluated to determine whether they were economically use-

ful. These:procedures provide a systematic review of the aircraft

design so that, in the absence of real experience, the best [mainte-

nance] plocess can be utilized for each component and system.

The Boeing 747 maintenance program so developed was the first:attempt

to apply reliebility-centered mait;tenance concepts. This program has

been successful.

Subsequent improvements in the decision-diagram approach led

in 1970 tc a second document, MSG-2; AirlinclMarrrrfncturcr Mni~rtcnnricc

Program Plnnnitlg Documort, which was used to develop the scheduled-

maintenance programs for the Lockhred 1011 and the Douglas DC-lo.$

These programs have been successful. MSG-2 has also been applied to

tactical milit*.y aircraft such # i s the McDonnell F4J and the Lockheed

P-3, and a similar document , 1,epared in Europe was the basis of the

initial scheduled-maintenance programs for such recent aircraft as the

Airbus lndustric A-300 and the Concorde.

The objective of the techniques outlined by MSG-1 and MSG-:! was

tc develop a qcheduled-maintenance program that assured the maxi-

mum safety and reliability of whicn the equipment was capable and

would meet this requirement at the lowest cost. As an example of the

economic benefits achieved with this type of under traditional

maintenance policies the initial program for the Douglas DC-8 included

scheduled overhaul for 339 items, w h e r ~ a s initial progranl for the

the

DC-10, based on MSG-2, assigned only seven items to overhaul. One of

the items 110longer subject to an overhaul limit in the later progr.:! II was

the turbine engine. Elimination of this scheduled task qot only led to

major reduct,ons in labor and materials costs, but also reduced the spare-

engine inventory required to cover shop activities by more than 50

percent. Since engines for larger airplanes now cost upwards of $1

million each, this is a respectable saving.

'747 hlaintcnance Steering Group. 1111r1dl~ooA: Mr~itltc'tra~l~.r E~~slrrr~tiotr l1ro,.rr~ttrD r l ~ c - l ~ ~ l r -

r~tlrl

ttrc3tlt( M S G - I ) . Air Transport Association, July lo, 1UhA.

t f l , r l r m l Azliatiotl Adtttitlistrntiott Crrtificriticlrl l-'rt~ccdltres,May 19. 1972, par. 3036.

S A i r l i t ~ z l M n t ~ ~ c f r ~ ~ t ~ l t ~ tl ' ~ t nP~r lo~ ~ n t t P / ~ l l t l ~ ~ l) ~ C I O ~ I M ISI C -: 2 , Air Transport

Mt~it t ~r ~ t O ~ ~

Association, H & M Subcommittee, Marcy 25, 1970. SECTION 1 . 1 5](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nowlanandheapercmstudy-usdodfunded-130102173537-phpapp02/85/Nowlan-and-Heape-RCM-Study-US-DoD-funded-25-320.jpg)

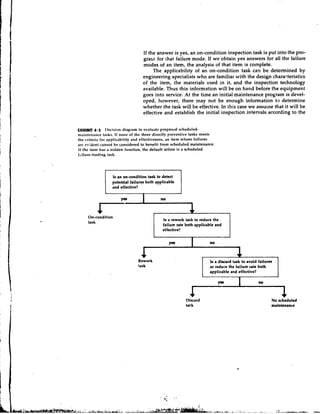

![modem design practices, however, very few items fa]! into this category,

either because an essential function is provided by more than one source

or because operating safety i s protected in some other way. Similarly,

hidden functions must be protected by schedultd maintenance, both

to ensure their availability and to prevent exposure to the risk of a

multiple failure.

In all other cases the consequences of failure are economic, and the

value of preventive maintenance must be measured in economic terms.

In some cases these consequences are major, especially if a failure

affects the operational capability of the equipment. Whenever equip-

ment must be removed from service to correct a failure, the cost of fail-

ure includes that loss of service. Thus if the intended use of the eauip-

ment is of significant value, the delay or abandonment of that use

will constitute a significant loss-a fact that must be taken into account

in evaiuating the benefit of preventive maintenance. Other failures will

incur only the cost of correction or repair, and such failures may well be

tolerable, in the sense that it is less expensive to correct them as they

occur than to invest in the cost of preventing them.

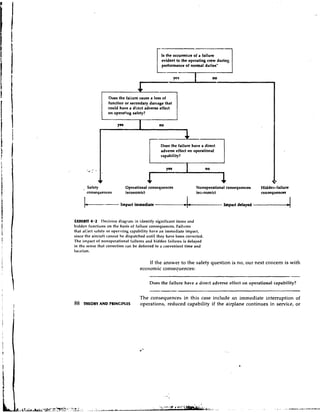

In short, the driving element in all maintenance decisions is not

the failure of a given item, but the consequences of that failure for the

equipment as a whole. Within this context it is possible to develop an

efficient scheduled-maintenance program, subject to the constraints of

satisfying safety requirements and meeting operational-performance

goals. However, the solution of such an optimization problem requires

certain specific information which is nearly always unavailable at the

time an initial program must be developed. Hence we also need a basic

strategy for decision making which provides for optimum maintenance

decisions, given the information available at the time. The process of

developing an initial RCM program therefore consists of the following

steps:

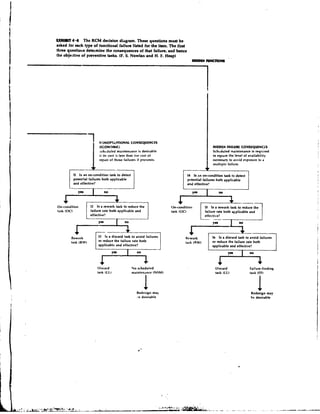

b Partitioning the equipment into object categories to identify those

items that require intensive study

b Identifying significant items, those whose failure would have safety

or major economic consequences for the equipment as a whule, and

all hidden functions, which require scheduled maintenance regard-

less of their significance

b Evaluating the maintenance requirements lor each significant item

and hidden function in terms of the failure consequences and select-

ing only those tasks which will satisfy these requirements

b Identifying items for u.hich no applicable and effective task can be

found and either recommending design changes if safety is involved

or assigning no scheduled-maintenance tasks to these items until

further information becomes available

I-,.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nowlanandheapercmstudy-usdodfunded-130102173537-phpapp02/85/Nowlan-and-Heape-RCM-Study-US-DoD-funded-27-320.jpg)

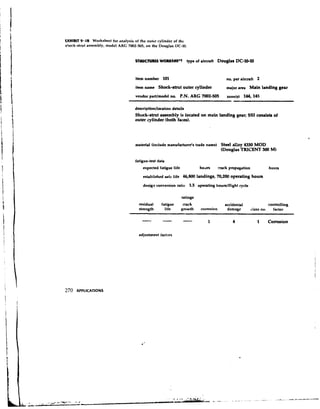

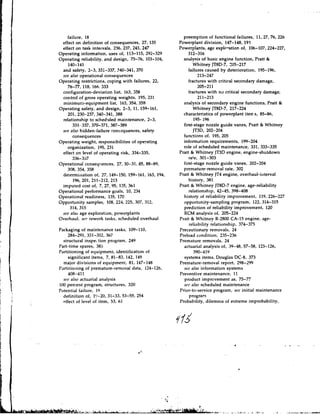

![fail (90 percent survive beyond this age):

.lo

[(age at P = 1) t (age at P = .90)] X -2

The next incremental area represents the contribution to the average life

of the next 10 percent of the units that fail:

[(age at P = .9Q + (age at P = .80)] X -

.10

2

and so on. Completion of this computation for the entire area under the

curve would show that, with no age limit, the average life expected for

each engine in service would be 1,811 hours.

Note, however, that an age limit of 1,000 hours removes all the sur-

viving units from service at that age. In this case, therefore, the area

under the curve represents only the area up to that age limit. The proba-

bility of survival to 1,000 hours is .692, so the contribution of any sur-

viving unit to the average life is only 1,500 hours X ,692 = 692 hours.

This contribution, added to the incremental contributions above it for

the units that failed, yields an average realized life of 838 hours for faded

and unfailed engines. Any engines that would have survived to ages

higher thtn 1,000 hours, and thus have added to the average life, do not

count. The average lives that would be realized with other age limits

in this case are as follows:

age limit average realized life

1,000 hours 838 hours

2,000 hours 1,393 hours

3,000 hours 1,685 hours

No limit 1,811 hours

PROMBILITY DWSllY OF FNLUUE

The probability that an engine in Exhibit 2.9 will survive to 1,000 hours

is ,692, and the probability that it will survive to 1,200 hours is ,639. The

difference between these probabilities, .053, is the probability of a fail-

ure during this 200-hour interval. In other words, an averaae of 5.3 out

of every 100 engines that enter service can be expected to fail during..,

this partic~tlarinterval. Similarly, an average of 5.0 engines can be ex- '.

pected to fail during the interval from 1,200 to 1,400 hours. This measure ,

is called the probnbility density of failure. 7

Exhibit 2.10 shows the probability densities for each 200-hour

age interval, plotted from the probabilities of survival at each age. A

decreasing percentage of the engines will fai! in each successive age

interval because a decreasing percentage of engines survives to enter

42 THEORY AND PRINCIPLS that interval.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nowlanandheapercmstudy-usdodfunded-130102173537-phpapp02/85/Nowlan-and-Heape-RCM-Study-US-DoD-funded-62-320.jpg)

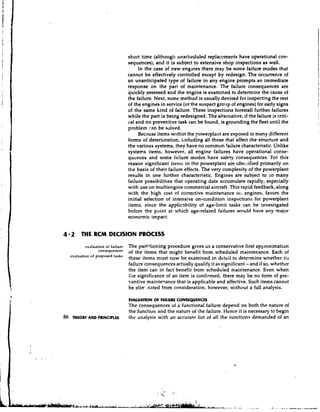

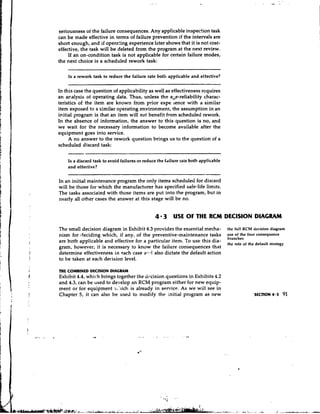

![(or other equipntent)

] Systems I

4.1 P~rtitioning aircraft for preliminary identitication of

an

significant iteins. The equipment is fin' partitioned to show all items

in descending order of comp:exity. rhose items wbose failure clcariy

tias nn sig~tific~nt con^-quencrs a! the equipment level are then p m ~ e d

from theqree, leavdg t!ie set oi ikms on which maintenance studies

mu . 5r cdhducted. E2ch significant itt?, will include as failure

r n ~ ~ rall ~ fai:ure possibilities it contains.

i e the

Tire obiectiv?, however, is to ftnd the tnos: convenient level of each

s;rstem or assembly to classify as significant. The level must be !ow

enougn to znsure that no important fai!ure possibilities are overlooked,

but high encjugh fdr the loss ol function to have an impact on the equip-

ment itself, since ihc consequences cf a functional failure are significant

only at the equipment level- that is, fzr the aircraft as a whole.

Once the optinlum level of item has been selected for study in each

x s e , we can prune the "trel?" back to a set of several I~undred poten-

tially significart items with the assurance that any failure possibilities

they include at lower levels will be taken into account as failure modes.

11s a n example, consider the engirie described in Section 3.1, in which

fai1u:e oi one or r;lore individual tie bolts in a set of 24 was defined as

a potcntial failure. Although this might be viewed as a functional fail-

ure of the tie bolt, thd failure of a single bolt does not affect engine

performance enough to be evident to the operating crew; consequently

the tie bolt is not a significant item. It does, htjwever, have a hidden

82 THkORY AND PRlNClPLfS function, and if enough tie bolts failed, the resulting multiple failure](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nowlanandheapercmstudy-usdodfunded-130102173537-phpapp02/85/Nowlan-and-Heape-RCM-Study-US-DoD-funded-102-320.jpg)

![airplane is desipned. For example, one of the load requirements for

structures in the commercial-transport category is defined as follows:*

25.341 Gust Loads

a The airplane is assumed to be subjected to symmetrical vertical.

gusts in level flight. The resulting limit load factors must cor-

respond to the conditions determined as follows:

I Positive (up) and negative (down) raugh air gusts of 66 ips

at V H [the design speed for maximum gust intensity] must

be considered at altitudes between sea level and 20,000 feet.

The gust velocity may be reduced linearly from 66 fps at

20,000 feet to 38 fps at 50,000 feet.

2 Positive and negative gusts of 50 fps at V(.[the design cruis-

ing speed] must be considered at altitudes between sea level

.r.d 20,000 feet. The gust velocity may be reduced Ilnearly

irolil 30 fps at 20,000 feet to 25 fps at 50,000 feet.

3 Positive and negative gusts of 25 fps at V,, [the design dive

speed] must be considered at altitudes between sea level

and 20.000 feet. The gust vdocity may- be reduced linearly

fro111 25 fps at 20,000 feet to 12.5 fps at 50,000 fret.

During the development and certification of any new aircraft the

manufacturer conducts numerous tests to confirm that each structural

assembly can withstand the specified design loads without damage or

- permaxlent deformation. Design loads with this objective are called limit

loads. There are also requirements that the structure be able to with-

stand at least 150 percent of the limit load without collapsing (experi-

encing a functional failure). When design loads are factored upward

in this way they are called ultimate loads. The present airworthiness

requirements for design strength have been effective in protecting

against functional failures as long as the specified load-carrying capa-

bilities of the structure are preserved.

After the airplane enters service the operating organization is

responsible both for preserving the design strength of the structure and

also for ensurinb that the operating gross weight of the airplane does

not exceed the maximum weight at which the structure can satisfy the

various l o ~ drequirrments.

THE FATIGUE PROCUS

All the loads to which an aircraft structure is subjected are repeated

rnany times throughout the col;rse of its operating life. Although ar.y

single load application may be only a fraction of the load-carrying

capability of the element, the stress impos.ld by each one reduces the

*F~.drrnl Avintiot~ R~-&rtlatiotrs,Airworthiness Standards: Transport Categoty Airpl'lnes,

sec. 25.341, effcclivc Februar).. 1, 19h5.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nowlanandheapercmstudy-usdodfunded-130102173537-phpapp02/85/Nowlan-and-Heape-RCM-Study-US-DoD-funded-251-320.jpg)

![and the size of the maintenance crew, it may take the airplane out of

senrice fot a week to several months.

The first of these complete inspections is a very important part of

the age-exploration program, since it incl~rdesmany inspections that

are being performed for the first time. The first airplane that ages to the

initial interval becomes the inspection sample; the findings for each

item are carefully evaluated, tasks and intervals for individual items

are adjusted as necessary, and the conservative initial inkerval for the

D-check package is extended. Consequently, although external inspec-

tions fire performed on every airplane, most internal items will be

inspected at the initial interval only on the first one or first few air-

planes to reach this age limit. They will, however, be inspected at suc-

cessive]!~ higher ages as the equipment ages in service, often 0x1 a fleet-

leader sampling basis.

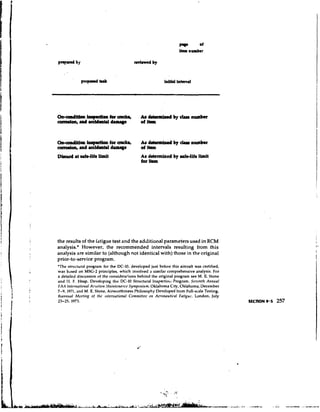

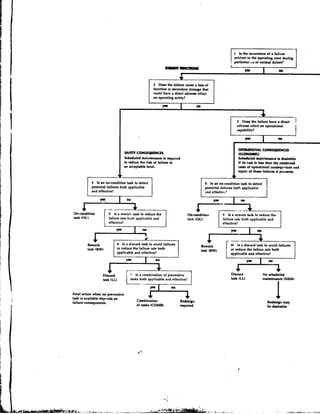

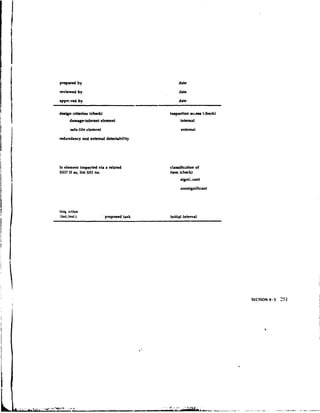

9 - 4 RCM ANP.3SIS O STRUCTURAL ITEMS

F

analysis of damage-tolerant As we saw in Chapters 7 and 8, RCM analysis of systems and power-

rlrmcnts

plant items may fall in any branch of the decision diagram. In contrast,

analvsis oi safe-litr rlr~nents

all structurally significant items fall in the safety branct and the eval-

uation of proposed tasks can have only one of two possible outconies

(see Exhibit 9.9). This is true no matter which of the structural functions

we consider. As an example, one function of the aircraft structure is to '

permit lifting forces to balance the weight of the airplane. Although

most uf the lift is provided by the wing, its center of lift does not neces-

sarily coincide with the airplane's center of gravity, and the horizontal

stabilizer must provide a balancing load that brings the vertical folces

into equilibrium. The portions of the structure ~ssociatedwith this

function, therefore, are the wing, the fuselage, and the horizontal tail.

The first question is whether a loss c.f the balancing function will

be evident:

1 Is the occurrence of a failure evident to the operating crew during

performance of nonrlal duties?

The answer is yes, of course, since a loss of this function as the result

of a structural failure would be a!l tot>evident, not only to the crew, but

to any other occupants of the airplane as well.

Next we would ordinarily examine the various failure modes that

could cause such a failure. In the case of structural items, however,

the failure modes all involve the fracture of a load-carrying metnbvr.

252 AHLICA~~N~ Thus the following question relates to any of the failure possibilities:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nowlanandheapercmstudy-usdodfunded-130102173537-phpapp02/85/Nowlan-and-Heape-RCM-Study-US-DoD-funded-272-320.jpg)