ZAHA RADm ARCHITECTS, BEUING CENTRAL BUSINESS DISTRICT COM.docx

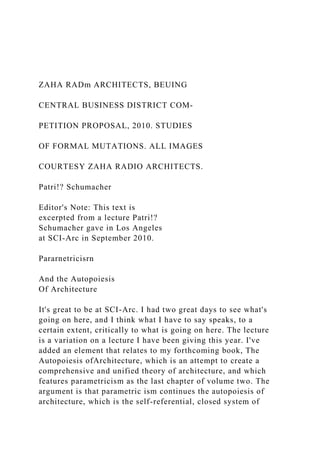

- 1. ZAHA RADm ARCHITECTS, BEUING CENTRAL BUSINESS DISTRICT COM- PETITION PROPOSAL, 2010. STUDIES OF FORMAL MUTATIONS. ALL IMAGES COURTESY ZAHA RADIO ARCHITECTS. Patri!? Schumacher Editor's Note: This text is excerpted from a lecture Patri!? Schumacher gave in Los Angeles at SCI-Arc in September 2010. Pararnetricisrn And the Autopoiesis Of Architecture It's great to be at SCI-Arc. I had two great days to see what's going on here, and I think what I have to say speaks, to a certain extent, critically to what is going on here. The lecture is a variation on a lecture I have been giving this year. I've added an element that relates to my forthcoming book, The Autopoiesis ofArchitecture, which is an attempt to create a comprehensive and unified theory of architecture, and which features parametricism as the last chapter of volume two. The argument is that parametric ism continues the autopoiesis of architecture, which is the self-referential, closed system of

- 2. communications that constitutes architecture as a discourse in contemporary society. The book is in two volumes. Volume one, a new framework for architecture, is coming out in December [released December 7,2010] and then a new agenda for architecture appears in volume two, probably four to six months later. It is difficult to summarize, but just to raise a bit of curiosity about this, I will make an argument for a comprehensive unified theory is of interest. A comprehensive unified theory of and for architecture is important if you are trying to lead 400 architects across a multiplicity of projects, touching all aspects and components of contemporary architecture in terms of programmatic agendas and at all scales. With a unified theory one is better prepared to manage the different designs, designers, and approaches that run in different directions, fight each other, contradict each other, and stand in each other's way. I am also teaching at a number of schools, the Architectural Association Design Research Laboratory [AA DRL] being one of them, an expanding group that is now 150 to 160 students. Here again there is an issue in trying to converge efforts so that people don't trip over each other and get in each other's way. The need for a unified theory is first of all to eliminate contradic- tions within one's own efforts - so one doesn't stand in one's own way all the time. If you go around from jury to jury, from project to project, you one thing here, another thing there, and further ideas come to mind; by the third occasion 63 you might be saying and doing things that don't gel, don't cohere. You might be developing ideas about architecture's societal function. You might be concerned with what is architecture, what is not architecture, to demarcate against

- 3. art, engineering, etc. You might think of yourself as pan of something like an avant-garde and try to develop a theory of the avant-garde. Or think about design media, the role of media theory; about design processes and design process theory. You wonder about aesthetic values and whether the notion of beauty is still relevant. Or you try to develop a theory of beauty, an aesthetic theory. And you're concerned with phenomenology. Then there's perception - how do you perceive space, subjects in space? Then it goes on. The concept of style: Is it still relevant? Then you try to develop a theory of style. You try to read the history of architecture in a cer- tain fashion ... and you do all this to position yourself with respect to contemporary architecture. These are the compo- nents that different authors, different thinkers, might un- dertake and spend half their careers on. Some of us might do two or three of these. At a certain stage it makes sense to ask whether these things can be brought into a coherent system of ideas where they forge a kind of trajectory that has to do with guiding practice. You can only lead a coherent practice with a deep and comprehensive theory. No one has attempted a unified theory for architecture since Le Corbusier, and perhaps the book The International Sryie, and perhaps the work of Christian Norberg-Schultz. But for a long time it has been nearly taboo even to start thinking about such an idea. I find it very interesting that the concept of style, like the International Style, returned after it had been abandoned by most of the early modernists. Modernism - the International Style - dominated the trans- formation of our built environment for 50 years and gener- ated an unprecedented level of material freedom and plenty, aligned, of course, with the growth of industrial civilization. In the 1970s it became clear that the principles and values that had defined modern architecture for half a century were no longer the principles and values through which architecture could facilitate the further progress of world civilization.

- 4. Modernism experienced a massive crisis, was abandoned. Everything had to be questioned, rethought, which led to free rein, freewheeling, browsing, and brainstorming. This also brought forth a new cast of characters, a sense of pluralism, and a sense that all systems (grand narratives) are bankrupt. That doesn't mean that aU attempts to cohere a unified theory are to be dismissed forever. After a period of questioning, brainstorming, and freewheeling experimentation, new pro- visional conclusions must be drawn, decisions must be made on how to move a project forward in a clear way. The neces- sity of this cannot be denied. So, to raise some curiosity about this idea, let me discuss the chapter structure of volume one. After the introduction there is a chapter on architecture theory, which is put for- ward as an important, necessary component of architecture. It actually marks the inception and origin of architecture with Alberti 500 years ago in the early Renaissance. That's where I say architecture starts. Everything before that was not architecture, it was some form of traditional building. Most of the book is an attempt to observe architecture and its communication structures, key principles, distinctions, methods, practices. It's a comprehensive discourse analysis of the discipline, and from that develops a normative agenda of selecting, or filtering out, the pertinent tendencies, the permanent communication structures, and the variable communication structures that have been evolving. All this is elaborated in order to forge a statement and position on how to move forward. To make this more digestible I extract poignant theses from the theory, and I will just read a few. Thesis one is that the phenomenon of architecture can be most adequately grasped if it is analyzed as an autonomous network or auto poetic system of communications. So I am not talking about architecture as simply a collection of build-

- 5. ings. I'm not talking about it as a profession or a practice. I'm not talking about it only as an academic discipline. Rather, I am concerned with how all of these activities are joined to- gether to create a system of communications. Thesis four states there is no architecture without theory. Thesis six contains the notion that resolute autonomy, or what I call self-referential closure, is a prerequisite of archi- tecture's effectiveness in an increasingly complex and dy- namic social environment. The notion of a self-enclosed autonomy of the discipline means that we as architects, and as a discourse as a whole, need to define the purposes that guide us, the conceptual structures and modes of arguments that are legitimate and meaningful to us, the tasks to focus on and how to pursue them. The kind of network of communi- cations that we constitute determines this. In contemporary society there is no other authority we can appeal to which would instruct architecture with respect to the built envi- ronment and its evolution. Neither politics, nor clients, nor science, nor morality. We have the burden as a collective to determine the way forward. That's what I mean by autonomy 64 Winter 2011 65 - the autonomy to adapt to an environment and to stay rel- evant in it. And that is not I also discovered that only by differentiating the avant- garde as a specific subsystem can contemporary architecture actively participate in the evolution of I believe that institutions like SCI-Arc and the AA, which seem to be one step removed from the burdens of state-of-the-art solutions here and now, are a condition for archi-

- 6. tecture to rethink and upgrade itself continuously. Thesis ten suggests that in a society without a control center, architecture must regulate itself and maintain its own mechanisms of evolution in order to remain adaptable in an ecology of evolving societal subsystems. These subsystems constitute society according to the notion of society underly- ing this discourse. There can be no external determination imposed upon architecture, neither by political bodies nor by paying clients, except in the negative, trivial sense of disrup- tion. Yes, they can stop your project. Maybe they can clamp down and deny permission, but they obviously cannot con- structively intervene. The same occurs with other so-called subsystems of society, like the legal system, science, the arts, etc. They are all self-regulating discourses. Thesis 16 suggests that avant-garde styles are designed research programs. IfI talk about style or use the concept of style I am not necessarily alluding to all its connotations. I am making an effort to redefine style as a valid category of contemporary discourse, because to just let it drop to the side would be an impoverishment of contemporary discourse. The notion of style is one of the few ideas that is meaningful beyond the confines of architectural discourse. For the world at large it's the primary category of understanding architec- ture, and we need to engage with that. All avant-garde styles are design research programs. They begin as progressive design research programs, and parametricism is now in that phase. They mature to become productive dogmas, which happened with modernism. And there is productivity in the ability to routinize insights for rapid dissemination and ex- ecution. And obviously all styles end up as degenerate dogmas. That is their trajectory. Thesis 17: Aesthetic values encapsulate a condensed collective within useful dogmas. Their inherent

- 7. inertia implies that values progress via revolution rather than evolution. Aesthetic values obviously shift with historical progress. You need to relearn your aesthetic sensibilities to for moral sensibilities. I am arguing, for instance, that mini- malist sensibilities have to be fought and suppressed because they don't allow you to adapt to contemporary life. Thesis 19: Architecture depends on its medium enor- mously. Parametricism is also a product of the development of the medium of architecture. Architectural communication is happening primarily within the medium of the drawing, becoming the digital model, becoming the parametric model, and the network of scripts. Architecture depends on its me- dium in the same way the economy depends on money and politics depends on power. These specialized media sustain a new plane of communication that depends on the of the medium, which remains able to inflationary tendencies. If you overdo make-believe reality, there is a but without this comoel1lng medium you would never be able to convince or anybody to project complex, large-scale find those that are productive and viable and that allow you to exist and be oroductive in contemporary life. The same goes 66 Log 21 Winter 2011 projects into a distant future, or to coalesce the enormous amount of resources and people needed to support and believe 67

- 8. ZAHA HADID ARCHITECTS, BEIJING CENTRAL BUSINESS DISTRICT COMPE- TITION PROPOSAL, 2010. ZAHA RADID ARCHITECTS, BEIJING CENTRAL BUSINESS DISTRICT COMPE- TITION PROPOSAL, 2010. STUDIES OF FORMAL MUTATIONS. in a coordinated effort. Architecture, of course, with its increasing complexity of tasks and agendas, also needs to upgrade its medium, just as money did. Money is no longer just coinage; it became paper money, became electronic money. Administrative power is also benefiting from the microelectronic revolution in terms of administering, controlling, connecting, and directing. Each of these social subsystems has a specialized social medium. All these media evolve together with the tasks they take on. One more thesis, Thesis 23: Radical innovation presupposes newness. Newness is first of all just otherness. The new is produced by blind mechanisms rather than creative thought. Strategic selection is required to secure communicative conti- nuity and adaptive pertinence.

- 9. *** Now I want to talk a little about the theoretical sources that allow me to work out a comprehensive unified theory of ar- chitecture with confidence and conviction. To do that, one of the key things you have to grasp is the societal function, or the raison d'&tre, of architecture in the world why it came into being, why it took certain forms and moved toward certain developments, and what the best bet is for staying relevant and continuing to play an important role. This requires some sense of the overall social process and its workings. For the first decade of my architectural life, beginning in the early 68 Log 21 1980s, I looked at Marxism and historical materialism as the kind of overarching theoretical edifice through which to think what is going on in architecture. When I went into ar- chitecture at the University of Stuttgart, I was joining the late modern period. People were still convinced of modernism. There was still hi-tech - Norman Foster and Richard Rogers were still the prominent going tendency. I was into it, but one or two years into my studies, I discovered postmodernism in the writing of Robert Venturi and in charles jencks's The Language of Post-Modern Architecture. And so I changed, and, in fact, the university changed. And a few years later there was a radical shift to deconstructivism. It seemed that in the 1980s, every two or three years there was a revolution in style, in paradigm, in outlook, and in values. I think that period left a mark on some people's general philosophical outlook. Soon there was a pluralism of styles. It seems that since then the kind of monolithic, cumulative trajectory of modernism is a thing of a past era and that we're now living in a world of continuous flux and splintering, fragmenting trajectories and ever-changing values, but that it is a historical illusion. In my search for a credible theory of architecture and

- 10. theory of contemporary society I discovered Niklas Luh- mann's social systems theory. Luhmann's fundamental prem- ise is that all social phenomena or events depend on systems of communication. He steps back from Marxist materialism to a kind of abstraction, but one that I think is plausible. You always have to abstract to theorize. To focus on communica- tions is interesting, because if you think about everybody's life process - where the bottlenecks are, where the crux of your problems is, your issues - you are always coping with social systems, your ability to communicate within them, to find a position within them. Even the physical world only gets to you through systems of communication. For example, if you're struck by illness your main problem will be whether you have health insurance, whether you have people you can communicate with, whether you are embedded in a system of communications with rights and the ability to speak. If you want to traverse physical space your issue will be whether you have money, an airline ticket. The bottleneck will be traffic, other people's attempts to travel, security controls at airports, etc. You are protected if you have the ability to buy a hotel room, an apartment, switch on the heater, pay the bills. Com- munication structures everyone's interface with the physical world and our relations with each other. If you think about architecture as an inverted commerce, we construct projects only through communications, whether through drawings, 69Winter 2011 contracts, phone calls, emails: communications, upon com- munications, upon communications - that's what runs this world. Everything goes through that needle's eye. Luhmann's philosophy of history differs from both Marx's and Hegel's. I insist that an architectural theorist possess a

- 11. philosophy of history, a theory of historical development. Luhmann looks at history in terms of modes of social or soci- etal differentiation - the mark of epochs. Today societies are organized in terms of functional differentiation. This is what Luhmann calls functionally differentiated society, composed of the great function systems of society, themselves parallel systems that co-evolve as autonomous discourses, systems of communication like politics, law, economics, science, educa- tion, health, mass media, and art. A politician has no way of influencing your voice in terms of scientific truth, just as issues of law have nothing to say with respect to scientific knowledge. The economy is separate from politics and has its own autonomous domain and communication system based on money and exchange in the market. The reverse is also true: science can deliver knowledge, but what is to be done with that knowledge is a matter of the economy, or the political discourse, and science cannot instruct politics. The same is true for art and science. The beautiful cannot be sci- entifically determined, etc. This is Luhmann's picture of society, which I very briefly sketch here. Luhmann has in fact written comprehensive analyses of all these social subsystems, but he did not write about architecture. He fit architecture anachronistically - into the art system, but really didn't talk much about it. I have been reading Luhmann for about 15 years, and it in- creasingly occurred to me that architecture could be theorized in the same way. Architecture is one of those great function systems of contemporary society, our functionally differenti- ated society. Just a few more points about what that might mean. Luhmann discovers a series of important processes that deter- mine these different systems within the era of modernity. The emerging market-orientation of the economy, the liberaliza- tion of the economy, is the pertinent way for the economy to

- 12. become an autopoietic system. The political system has been evolving and succeeding through democratization, and only through democratization does it become a truly autopoietic, self-referentially closed system. The legal system found its autonomy and forward drive through positivism rather than natural law or God-given legal discourse. Art discovered its self-programming in romanticism. All of these mechanisms 70 Log 21 mean that these systems become autonomous and adaptive to each other. They become versatile, innovative, progressive, and ever-:evolving. All these processes are established some- where between 1800 and 1900. My thesis here is that the concept of space, or the spatialization of architecture, is the equivalent of the democratization of the political system, the liberalization of the economy, etc. As Luhmann was analyzing these different function sys- tems he realized that despite their differences - they share parallel structures and face parallel, or comparative, prob- lems: How could they demarcate themselves? How could they cohere around an elemental operation? How could they rep- resent within themselves the differences between them and their environment? He discovers that each of these systems has a binary code, programs that elaborate how the code val- ues will be used. Each has its specific medium, such as money for the economy, and they all have a unique societal function, which acts as a kind of evolutionary attract or for the differ- entiation and autonomization of that respective system. This unique and distinct function unfolds in a series of tasks. Each of these systems projected itself forward through something Luhmann called self-descriptions. This means that within each discourse there are theoretical reflections via great treatises, written accounts of trying to think through and

- 13. argue the function, the purpose, the raison d'~tre of each of the function systems. So within the political system there is political theory. The legal system developed together with jurisprudence. Science developed together with epistemology, the philosophy of science. And architecture has architectural theory, but only a deep and comprehensive kind of architec- tural theory functions as self-description. In volume two I go through some of them: Alberti's Ten Books on Architecture; Durand's lectures on architecture for the era of neoclassicism; Le Corbusier's Towards a New Architecture for modernism; and The Autopoiesis of Architecture for our time, for parametricism. We can identify in every function system a so-called lead distinction. The lead distinction for architecture is form versus function. You find it in Alberti. You find it in all major self-descriptions. This lead distinction is the re-entry of the system-environment distinction into the system. It represents the distinction of the system of architecture against its en- vironment - that is, against the totality of society - within architecture. So with the category of form, architecture rep- resents itself to itself as distinct from function, which is the category representing the external world reference of archi- tecture. The lead distinction of the economy is the distinction Winter 2011 71 of price versus value: price is the internal reference; value is the external reference. In science it is theory versus evidence, in the law, norm versus fact, etc. There are further parallels between these function systems. To identify the respective structure in architecture that coincides with the structures found in the other function systems has been a creative puzzle-solving exercise, but in the end a coherent picture

- 14. emerges that allows me to take a position with respect to all of the partial theories I have been developing over the years. Let me show a few pictures of MAXXI in Rome as a reminder that there's a certain credibility in realizing projects that follow the principles I'm talking about. The Rome proj- ect is a field project. It has a very stringent formalism. At the same time it is very capable of adapting to contexts, in terms of continuing field conditions, aligning with an urban grid on one side and with a separate urban grid on another, incorpo- rating existing architectures, and managing to create a coher- ent space around a corner. I would argue that it does a lot of difficult things with ease and elegance. Some of the strong alignments with the context go right through the building. There's a sense of bringing together disparate elements under a single formalism, with flow lines irrigating the space. One of the ambitions is moments of deep visual penetration, the legibility and transparency of complex organization. In the central communication hub, ramps and staircases follow the formal language of walls and ribs, creating something coherent. That's a precondition for generating an overall complexity without creating visual chaos. Although MAXXI was designed 10 years ago, it is a kind of early parametricist project. The proliferation of lines, bundling, converging, and departing from one another, creates a field space. *** So let me define parametricism. First of all, a conceptual definition: all elements of architecture have become para- metrically malleable. That's both fundamental and profound. The advantage of this is the intensification of relations both internally, within a design project, a building, and exter- nally, with its context and surroundings. This is a funda- mental ontological shift with respect to the base components and primitives constituting an architecture. For the previ-

- 15. ous 2,000 years, if you like, architecture was working with platonic solids, with rigid, hermetic, geometric figures, and just composing them. Compared with classical architecture, modernism was allowed to stretch proportions, was able to give up symmetries, and instead had a kind of dynamic 72 Log 21 equilibrium and more freedom that moved these figures from edifice to space with all of the advantages of abstraction and versatility that entails. But in terms of the base primitives, it was geometric figures and nothing else. If you look at the kinds of primitives we are working with today, however, it is a totally different world splines, blobs, nurbs, particles, all organized by scripts. I think it started with deconstructivism, to a certain extent, and then Greg Lynn talking about blobs in 1994-95. When we were teaching at Columbia in '93, we were creating dynamic, cross-inflected textures and fields. This was also the beginning of certain computational mechanisms. Instead of drawing with ruler and compass, making rigid lines and rigid figures, we worked with dynamical systems. That's a new ontology, which cannot but leave a profound, radically transformative mark on what we do. If we succeed, and I have no doubt parametricism will succeed, we'll change the physiognomy of this planet and its built environment, just the way modernism did for 50 years in the 20th century. The recession over the last two years put a bit of a damper on but that should not be misunderstood as a failure or refuta- tion of this kind of work. In fact, architecture continues to invest in digital technology, fabrication systems, etc., and any prohibitive cost is diminishing as a factor. An economic recession cannot stand in the way of universalizing these principles. Parametricism is the way we do urbanism and architecture now. 73

- 16. ZAHAHADID ARCHITECTS, MAXXI: MUSEUM OF XXI CENTURY ARTS, ROME, 1998-2009. PUBLIC PLAZA AT ENTRY. PHOTO: IWAN BUN. Winter 2011 ZAHA RADID ARCHITECTS, MAXXI: MUSEUM OF XXI CENTURY ARTS, ROME, 1998-2009. PHOTO: IWAN BAAN. '" '" '" So the thesis is clear: parametricism is the great new style after modernism. I consider postmoderrusm and deconstructivism to be transitional styles, or transitional episodes. I think that architectural innovation and history proceed by the succession of styles. These are the great paradigms and research pro- grams by which architecture redefines itself. Postmodernism and deconstructivism are temporary phenomena, a decade each. Parametricism is already 15 years down the line. Design research programs establish the conditions for the collec- tive design research needed to agree on the fundamentals that add up to an overall research project. If you are fighting over fundamentals every time you start a new project, you cannot progress. Here I draw not on Luhmann so much as on the philosophy of science as projected by Thomas Kuhn, theorizing paradigm shifts, and in particular I draw on Imre Lakatos's theory of scientific research programs. Science is founded, or re-founded, with certain paradigmatic categories, principles, anticipations, and intuitions about how a science

- 17. could progress, and on that basis, after a revolutionary period of paradigm exploration, a new paradigm or research pro- gram has to emerge and win the competitive battle, and then reconstitute cumulative research. Like a research program, a shared style implies that you are formulating pertinent desires, framing and posing problems to work on, and stra- tegically constraining the solution space. We are identifying Winter 201174 Log 21 problems and trying to solve these problems by means of parametric systems, by exploring the power of malleability in the elements. The style imposes a formal a priori. There are very strong analogies in science. For example, Newton set up a certain set of principles by which every phenomenon was investigated, probed, and modeled. From problem to prob- lem, the same principles are held steady, otherwise there is no testing, no research. Innovation requires this kind of steady, collective effort. It is the condition of any progress. We can think of the history of architecture in terms of cycles of innovation and shifts between revolutionary periods, when the paradigm is no longer working, as happened in the late '60s, the '70s, and early '80s. You couldn't really go on after Pruitt-Igoe was imploded. The principles that architects were relying on were exhausted. That's also why SCI-Arc was founded because the old university way of doing things couldn't continue, it was bankrupt. The situation required a sense of freewheeling brainstorming. Architecture drew on philosophers, and fundamental questions were asked. It's interesting that today philosophy has receded, we've reached a different stage. We have drawn conclusions and learned our lessons; we have internalized new forms of thinking and argumentation, new values, new philosophies, and now we have to forge ahead, developing a new architecture. Every new generation has to relearn the raison d'~tre of what we do,

- 18. but that doesn't mean that what we are doing is up for discur- sive destruction or disposition every second year. At the early stages of a new convergence you have to become accustomed to living with a lot of failures, a lot of difficulties, a lot of implausibilities. That's why we need the avant-garde: where there is methodical tolerance, where there are dry runs, experiments, and manifesto projects, and where you can't expect to immediately compete with the mainstream state of the art. You have to stick to your principles and not allow pragmatic concerns to push you to fall back on old models, old solutions, which are easy and accepted. You've got to go it the difficult way. You've got to go it the consistent way. The dogmatic way. That's what Newton did also. It's important to give a conceptual definition of para- metricism in terms of parametric malleability, but there is also an operational definition of parametricism. When I first started to talk about parametricism I was talking about for- mal heuristics, but now I find it necessary also to talk about functional heuristics, because a style is not just a matter of form and structured formalisms. Each style also introduces a particular attitude and way of comprehending and handling 7S ZAHA RADIO ARCHITECTS, NYC 2012 OLYMPIC VILLAGE COMPETITION PRO- POSAL, NEW YORK, 2004. BIRD'S-EYE VIEW AND PERSPECTIVE. functions and program. Any.reri()u.r style must take a posi-

- 19. tion on these issues, and I think we have a different attitude and position with respect to function than the modernists. We need both functional heuristics and formal heuristics. This is not something I am dogmatically imposing, I'm just observ- ing that I, my friends, my students, naturally adhere to these principles without faiL Their hand would fall off rather than draw straight lines. Is anybody here drawing a triangle, a square, or a circle? Ever again? No! Postmodernism and deconstructivism celebrated collage, interpenetration, and layering in an unmediated way, but this notion of pure difference and collage, which is in fact the default condition of spontaneous urban development after the collapse of modernism, is invested only in just the pro- liferation of pure difference, of piling up unrelated elements against unrelated elements, etc. But that is taboo within the discourse of parametric ism. Modernism, seriality, repetition are out of the question. Instead everybody is putting down their own shape, form, material- all uncoordinated. So, if the modernist recipes as well as their spontaneous antitheses are rejected, where are we going? We are trying to create a second nature, a complex var- iegated order, at Zaha Hadid Architects and at the different schools where we teach. I am trying to formulate the positive principles that determine the new physiognomy, that define a new way of working with parametrically malleable, soft forms. Soft forms are able to incorporate a degree of adap- tive intelligence. They are no longer just forms, but may have gravity or structural constraints, material constraints, inbuilt logics that make them intelligent. The second positive principle, or dogma, which all of you here always demand of yourselves and which your teachers 76 Log 21

- 20. will demand of you as students, is differentiation. If you are building differentiated systems, whether you work only with smooth gradients, or whether you work with thresholds or singularities, you will always work with laws, with rule- based systems of differentiation. These can be applied mean- ingfully, for instance, in the adaptation of facades to create an intelligent differentiation of elements. You can do this by taking data sets like sun exposure maps and make them drive an intelligent differentiation of brise-soleil elements, which are scripted off the data set. But you can also apply this kind of technique to urbanism. We're talking about urban fields, about the lawful differentiation of an urban fabric according to relevant data sets. Once you have a series of these internally differentiated systems, you can think about establishing correlations be- tween them, where one system drives the other. These are all co-present systems, which become representations of each other. They might be ontologically rather different, radically other. There will be multiple systems, each differentiated. Then you can establish correlations. Here, just a simple exam- ple, are our towers for the New York Olympic Village, which interface with the ground and create a kind of resonance with it. The way the facade is correlated with the horizontal sec- tion of a tower has to do with the programmatic shift from an office area to a residential area. And of course you can try to mechanize these correlations in terms of associative logics. What is important here for me is that we are moving from single-system projects, which are a kind of first stage - too abstract to really grip in reality to the inter-articulation of multiple subsystems, to multisystem correlations. The principles of parametricism, in terms of its heuris- tics, its operational definition, provide failsafe tools for criti-

- 21. Winter 2011 77 cism and self-criticism of project development and project enhancement. You can always identifY where the rigid forms still persist, where there is still too much simple repetition, where there are still unrelated elements. You can always ask for further softening, further differentiation, and further correlation of everything with everything else. There's always more to script and correlate to intensifY the internal consistency and cross-connections and resonance within a project and to a context. It's a never-ending trajectory of a project's progression. The intensification of relations in architecture reflects the intensification of communication among all of us, everyday and with everything. A building can no longer be a silo out in the greenfield; it needs to be connected in an urban texture, needs to be accessible, have internal differentiation, yet have a sense of continuity. Functional heuristics. There are some taboos in terms of handling functions. We avoid thinking in terms of essences. We avoid stereotypes and strict typologies. We also avoid designating functions to strict and discrete zones. These are taboos for all of us. Instead, we think in terms of gradient fields of activity, about variable social scenarios calibrated by various event parameters. We think in terms of actor-artifact networks. That's the way we break down a program, a task. And that makes sense, because the formal heuristics and func- tional heuristics coalesce, make sense together. To translate these functions into form you need the formal heuristics I discussed earlier. Clearly, parametric systems or techniques could be used as technologies of design by modernists like Norman Foster; they could also be used by neoclassicists. The point is that

- 22. the tools themselves have great potential, but we need to drive these potentials and draw decisive conclusions and give value and direction to the utilization of these tools. That is the difference between a set of techniques and a style, which depends on these techniques, albeit not exclusively, but drives them to a new destiny. Foster's British Museum dome could only have been done with parametric tools. Every joint is dif- ferent, every panel is different. The use of parametrics made this possible, but the spirit of this application is the spirit of modernism of neutralizing the differences, making them inconspicuous. Here all elements are different but they want to appear the same. Against that I put forward a new kind of "artistic project," the project of driving the conspicuous amplification of differences. So a difference in curvature is transcoded into radically different conditions of ribbing, of gridding, of dense networking, perhaps engendering a phase 78 PATRIK SCHUMACHER IS A DIRECTOR OF ZAHA HADm ARCHITECTS AND PROFESSOR AT INNSBRUCK UNIVER- SITY. HE IS ALSO CO-DIRECTOR OF THE DESI<TN RESEARCH LABORATORY AT THE ARCHITECTURAL ASSOCIATION SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE, LONDON. Winter 2011 change at a certain threshold. This is much more prone to

- 23. the development of versatile conditions and different atmo- spheres, which bleed into each other instead of establishing disparate zones. I think our work forms a much more perti- nent image and vehicle of contemporary life forces and pat- terns of social communication than that big Foster dome. This emphasis on differentiation, the amplification of de- viations rather than neutralization and compensation, is also related to the difference between exploratory design research and problem solving. Problem solving is the engineering side, the side of parametric technique. In contrast, when we are talking about parametricism as style, we're talking about teasing out the as yet unknown potentials of these techniques, but with the general direction clearly set by the parametricist heuristic principles. This has been going on for quite a while now. I believe that we are on the cusp of moving from an avant-garde condition into claiming the mainstream. Most of our projects, even most of our built work, are hypotheses, manifestos, but I think some of our projects go beyond that and are becoming compelling success stories in the real world. The projects now coming out of the office show the rich- ness of our formal vocabulary and the richness of types of structures we are addressing. There's a kind of unity within difference, or difference within unity, moving across various scales: endless forms. But these endless forms are there to or- ganize and articulate life. So formpo"Wers function. That's the new thesis. Spatial organization sustains social organization. Can we demonstrate, control, and predict this? To a certain extent, I would argue, we can. If we look at the history of parametricism, in fact it's the history of the whole evolution of architecture. The funda- mental thesis is that social order requires spatial order, that society doesn't exist without a structured environment, and that society can only evolve if it is able to enhance and intri-

- 24. cately structure its built environment as well. Architecture provides the necessary substrate of cultural evolution. 79 DocumentationBright LightAuthorDatePurposeProjected usage on shelter and meals program Shelter UsageThe Bright LightUsage Figures for 2010*DecNovOctSepAugJulSingle Rooms (5)118110112104106103Common Room 1 (15 max)448419434422421410Common Room 2 (15 max)432436412431405411Domestic Abuse Shelter (3)728781524754Total Client Days1070105210391009979978* Figures represent total occupancy for each month. Projected UsageYearClient Days200310,37113750200411,03813750200511,3111375020061 1,78713750200712,14213750200812,61713750200913,2461375 0201013,87513750201114,10413750201214,54513750 Projected Usage Client Days 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 10371 11038 11311 11787 12142 12617 13246 13875 14104 14545 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 13750 13750 13750 13750 13750 13750 13750 13750 13750 Year Total Client Days Projected 1 2 3

- 25. 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 A B C D The Bright Light Usage Figures for 2010* Dec Nov Oct Single Rooms (5) 118 110 112 Common Room 1 (15 max) 448 419 434 Common Room 2 (15 max) 432 436 412 Domestic Abuse Shelter (3) 72 87 81 Total Client Days 1070 1052 1039

- 26. * Figures represent total occupancy for each month. January 25, 2012 Ann Magee Assistant Financial Administrator State Dept. of Social Services 1 East Central Ave. Atlanta, PA 66601 Dear Ms. Magee: Thank you for your inquiries about The Bright Light. I am enclosing a complete usage report for 2010. As the following summary table indicates, we have seen increased use of the shelter in the second half of the year. Even if we take into account our severe winter, the shelter is being used at a greater rate than in any previous year. Our analyst has projected shelter usage for the next two fiscal years. Based on those projections, The Bright Light will need to start expanding its space within the next two years, or we will have to start sending people to other facilities. Currently, the closest facility is located 30 miles away in the town of Three Points. For many of our clients, this would not be a practical alternative. I hope this material helps you in organizing budget priorities for the next state budget. Please let me know if you need any more information. Regards, Peter Skinner Financial Director The Bright Light

- 27. Self-Check And Submit: Appendix C – Integrating Excel with other Office Applications, pgs EX C21 - EX C27 only Complete only the small section towards the end of Appendix C that begins with “Integrating Excel with other Office Applications”. Do not complete the rest of Appendix C on Creating a Shared Workbook. Submit the Memo Destination Word document and the Income Statement Source workbook Submit To Be Scored: Appendix C, Bright Light Case Problem The Bright Light Case Problem is not in your textbook. Complete this Case problem using the instructions listed below. Begin and Submit to the Final Project Dropbox when complete: Final Project – Tutorial 8, Case Problem 4, pgs 482-485 This project will comprise 20% of your grade. Please do not wait to begin this project until the last minute. It is a comprehensive assignment and will take a fair amount of time to complete. Double check your final product to make sure it is professional looking and error-free before turning it in. You will submit the following documents from the Alia’s Senior Living workbook: Documentation sheet, Invoice, Invoice formulas and Product Pricing and Shipping sheet. In step 4o, the best solution for the shipping cost is an IF Function with a nested vlookup (the IF checks if the subtotal is >=200 and thevlookup references the shipping cost table). Bright Light Case Problem Data files needed for this Case Problem:Usage.xlsx and Request.docx Problem: Peter Skinner is writing a letter to the state government to report on the shelter and meal programs used at

- 28. Bright Light. He has data in an Excel workbook and needs to incorporate the data into the letter he is composing in Word. Because the report will also include projections for the upcoming year, which he might modify, Peter wants to create a link between the information in the Excel workbook and the Word document. He also wants to embed in the Word document a chart that he has created in his workbook. He asked you to help link the two files. Complete the following: <![if !supportLists]>1. <![endif]>Open the Usage workbook located in the Appendix C misc folder, and then save it as Bright Usage. <![if !supportLists]>2. <![endif]>In the Documentation sheet, enter the date and your name, and then switch to the Shelter Usage worksheet. <![if !supportLists]>3. <![endif]>Open the Request document located in the Appendix C misc folder, and then save it as Bright Request. <![if !supportLists]>4. <![endif]>Return to the Bright Usage workbook, and then copy the range A2:G9 in the Shelter Usage workbook. <![if !supportLists]>5. <![endif]>Return to the Bright Request document, and then paste the selected range as a link below the first paragraph of Peter’s letter. <![if !supportLists]>6. <![endif]>Peter discovered that the number of client days in the domestic abuse shelter in December 2010 was actually 75, not 72. Make this change in the Bright Usage workbook, and then verify that the Bright Request document is automatically updated. <![if !supportLists]>7. <![endif]>Copy the Projected Usage chart from the Shelter Usage worksheet, and then embed the chart below the second paragraph in Peter’s letter (do not link the chart). <![if !supportLists]>8. <![endif]>Edit the embedded chart, changing the background color of the plot area from yellow to white.

- 29. <![if !supportLists]>9. <![endif]>Save and close the Bright Request and Bright Usage files. Print and submit the finished workbook to your instructor. DocumentationMortgage AnalysisAuthor:Date:Purpose:To calculate the monthly payment and total cost of a mortgage under different conditions MortgageMortgage AnalysisLoan Amount$250,000Interest Rate5.50%Years30Term (Months)360Monthly Payment($1,419.47)Total($511,010.10) INTRODUCTION Architectural Curvilinearity: The Folded, the Pliant and the Supple / Greg Lynn In 1993, Greg Lynn guest-edited an issue of Architectural Design dedicated to an emerging movement in architecture: folding. Lynn, a Los Angeles-based architect/educator with a background in philosophy and an attraction to computer-aided design, was the ideal person to organize this publication and, in effect, define the fold in architecture, a concept that generated intense interest

- 30. during the remainder of the decade. In his contributory essay, ''lrchitectural Curvilinearity: The Folded, the Pliant and the Supple," Lynn ties together a variety of sources-including the work of Gilles Deleuze, Rene Thom, cooking theory, and geology-to present an alternative to existing architectural theory and practice. He states that since the mid-1960s architecture has been guided by the notion of contradiction, whether through attempts to formally embody heterogeneity or its opposite; in short, postmodernism and decon- structivism can be understood as two sides of the same coin. Yet, for Lynn, "neither the reactionary call for unity nor the avant- garde dismantling of it through the identification of internal contradic- tions seems adequate as a model for contemporary architecture and urbanism." Rather, he offers a smooth architecture (in both a visual and a mathematic sense) composed of combined yet dis- crete elements that are shaped by forces outside the

- 31. architectural discipline, much as diverse ingredients are folded into a smooth mixture by a discerning chef. This new architecture, what Lynn calls a pliant, flexible orchitecture, exploits connections between elements within a design instead of emphasizing contradictions or attempting to erase them all together. Of equal importance is that this architecture is inextricably entwined with external forces, both cultural and contextual. Architects deploy various .. ,JJiJIIIiIIIIliii. ,j'"'ngies-including a reliance on topological geometry and "'u"al software and technologies-in the creation of their designs, II,,' Ihe resulting works tend to be curvilinear in form and inflected ....Ih the particulars of the project and its environment. In addition to Lynn's essay, Folding in Architecture, as the A/. hitectural Design issue was titled, included other texts by fig- ,,·os such as Deleuze, Jeffrey Kipnis, and John Rajchman, and '''presentative projects by architects like Peter Eisenman, Frank

- 32. ( inhry, and Philip Johnson. This list of distinguished collaborators ("fl' weight to the publication, intimating that the phenomenon "I the fold was already entrenched within architectural design. If Indeed it was, Folding in Architecture cemented the shift in (lfchitectural thought by identifying and highlighting this new mchitecture of smoothness. The importance of Lynn's special .,sue of Architectural Design was underscored by its reprinting in 2004 as "a historical document,"1 complete with new introductory nssays analyzing and situating the original publication as a guid- Ing force within twenty-first-century architectural discourse.2 Notes Helen Castle, "Preface," in Folding in Architedure, ed. Greg Lynn (London: Wiley-Academy. 2004), 7. 2 See Greg Lynn, "Introdudion," in Folding in Architecture, 8-13; and

- 33. Mario Carpo, "Ten Years of Folding," in Folding in Architecture. See also Branko Koleravic, ed., Architecture in the Digital Age: Design and Manufacturing (New York: Spoon Press, 2003), 3-10. 30 31 GREG LYNN ARCHITECTURAL CURVILINEARITY: THE FOLDED, THE PLIANT AND THE SUPPLE First appeared in Architectural Design 63, no. 3/4 (1993): 8-15· Courtesy ofGreg For the last two decades, beginning with Robert Venturi's Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture,' and Colin Rowe and Fred Koetter's Collage City,2 and continuing through Mark Wigley and Philip Johnson's Deconstructivist Architecture, archi- tects have been primarily concerned with the production of heterogeneous, fragmented and conflicting formal systems.

- 34. These practices have attempted to embody the differences within and between diverse physical, cultural, and social con- texts in formal conflicts. When comparingVenturi's Complexity and Contradiction or Learning from Las vegas with Wigley and Johnson's DeconstructionArchitecture it is necessary to overlook many significant and distinguishing differences in order to identify at least one common theme. Both Venturi and Wigley argue for the deployment of dis- continuous, fragmented, heterogeneous, and diagonal formal strategies based on the incongruities,juxtapositions and opposi- tions within specific sites and programmes. These disjunctions ,nult from a logic which tends to identify the potential con- 1I.IIIit'lions between dissimilar elements. A diagonal dialogue Iwlween a building and its context has become an emblem I", Ihe contradictions within contemporary culture. From the ', •.1It' of an urban plan to a building detail, contexts have been IIl1l1ed for conflicting geometries, materials, styles, histories, ,.lId programmes which are then represented in architecture as 11111' mal contradictions. The most paradigmatic architecture of t t1l' last ten years, including Robert Venturi's Sainsbury Wing of 'hI' National Gallery, Peter Eisenman's Wexner Center, Bernard I chumi's La Villette Park or the Gehry House, invests in the ,II ('hitectural representation of contradictions. Through con- II ad iction, architecture represents difference in violent formal • 1111 t1icts.

- 35. Contradiction has also provoked a reactionary response ,,, formal conflict. Such resistances attempt to recover unified .1Il'hitecturallanguages that can stand against heterogeneity. I !Ility is constructed through one of two strategies: either by ''('onstructing a continuous architectural language through historical analyses (Neo-Classicism or Neo-Modernism) or by ldt'ntifying local consistencies resulting from indigenous cli- mates, materials, traditions or technologies (Regionalism). rhe internal orders of Neo-Classicism, Neo-Modernism and Ilt'gionalism conventionally repress the cultural and contextual discontinuities that are necessary for a logic of contradiction. III architecture, both the reaction to and the representation of heterogeneity have shared an origin in contextual analysis. Both Iheoretical models begin with a close analysis ofcontextual con- ditions from which they proceed to evolve either a homogeneous or heterogeneous urban fabric. Neither the reactionary call for IInity nor the avant-garde dismantling of it through the identifi- t':ltion of internal contradictions seems adequate as a model for l'Ontemporary architecture and urbanism. GREG LYNN 33 32 In response to architecture's discovery of complex, dis- parate, differentiated and heterogeneous cultural and formal contexts, two options have been dominant; either conflict and contradiction or unity and reconstruction. Presently, an alter- native smoothness is being formulated that may escape these

- 36. dialectically opposed strategies. Common to the diverse sources of this post-contradictory work-topological geometry, mor- phology, morphogenesis, Catastrophe Theory or the computer technology of both the defense and Hollywood film industry- are characteristics of smooth transformation involving the intensive integration of differences within a continuous yet het- erogeneous system. Smooth mixtures are made up of disparate elements which maintain their integrity while being blended within a continuous field ofother free elements. Smoothing does not eradicate differences but incorporates3 free intensities through fluid tactics of mixing and blending. Smooth mixtures are not homogeneous and therefore cannot be reduced. Deleuze describes smoothness as "the continuous variation" and the "continuous development ofform."4 Wigley's critique of pure form and static geometry is inscribed within geometric conflicts and discontinuities. For Wigley, smoothness is equated with hierarchical organisation: "the volumes have been purified-they have become smooth, classical-and the wires all converge in a single, hierarchical, vertical movement. "5 Rather than investing in arrested conflicts, Wigley's slipperi- ness might be better exploited by the alternative smoothness of heterogeneous mixture. For the first time perhaps, complexity might be aligned with neither unity nor contradiction but with smooth, pliant mixture. Both pliancy and smoothness provide an escape from the two camps which would either have architecture break under the stress ofdifference or stand firm. Pliancy allows architecture to become involved in complexity through flexibility. It may be 34 ' ARCHITECTURAL CURVILINEARITY pn""ihlc to neither repress the complex relations of differences

- 37. "Ih fixed points ofresolution nor arrest them in contradictions, btu "ustain them through flexible, unpredicted, local connec- Ikllls. To arrest differences in conflicting forms often precludes ....ny of the more complex possible connections of the forms of .rc:hilecture to larger cultural fields. A more pliant architectural k'""ibility values alliances, rather than conflicts, between ele- "'t"IlIS. Pliancy implies first an internal flexibility and second a dc-,ll'ndence on external forces for self-definition. If there is a single effect produced in architecture by folding, .. will be the ability to integrate unrelated elements within a new tunlinuous mixture. Culinary theory has developed both a prac- tklll and precise definition for at least three types of mixtures. l'lll' first involves the manipulation of homogeneous elements; bt"lIling, whisking and whipping change the volume but not .ht" nature of a liquid through agitation. The second method ur incorporation mixes two or more disparate elements; chop- Pill){, dicing, grinding, grating, slicing, shredding and mincing rvisl'erate elements into fragments. The first method agitates • "ingle uniform ingredient, the second eviscerates disparate Ingredients. Folding, creaming and blending mix smoothly multiple ingredients "through repeated gentle overturnings wilhout stirring or beating" in such a way that their individual l'hnracteristics are maintained.6 For instance, an egg and choco- tilt' are folded together so that each is a distinct layer within a c:nntinuous mixture. Folding employs neither agitation nor evisceration but a .upple layering. Likewise, folding in geology involves the sedi- IUl'ntation of mineral elements or deposits which become _lowly bent and compacted into plateaus of strata. These strata Afl' compressed, by external forces, into more or less continu- IIUS layers within which heterogeneous deposits are still intact in varying degrees of intensity.

- 38. GREG LYNN 35 A folded mixture is neither homogenous, like whipped cream, nor fragmented, like chopped nuts, but smooth and heterogeneous. In both cooking and geology, there is no pre- liminary organisation which becomes folded but rather there are unrelated elements or pure intensities that are intricated through ajoint manipulation. Disparate elements can be incor- porated into smooth mixtures through various manipulations including fulling: "Felt is a supple solid product that proceeds altogether dif- ferently, as an anti-fabric. It implies no separation of threads, no intertwining, only an entanglement of fibres obtained by full- ing (for example, by rolling the block of fibres back and forth). What becomes entangled are the microscales of the fibres. An aggregate of intrication of this kind is in no way homogeneous; nevertheless, it is smooth and contrasts point by point with the space of fabric (it is in principle infinite, open and uninhibited in every direction; it has neither top, nor bottom, nor centre; it does not assign fixed or mobile elements but distributes a continuous variation}."? The two characteristics of smooth mixtures are that they are composed of disparate unrelated elements and that these free intensities become intricated by an external force exerted

- 39. upon them jointly. Intrications are intricate connections. They are intricate, they affiliate local surfaces of elements with one another by negotiating interstitial rather than internal connec- tions. The heterogeneous elements within a mixture have no proper relation with one another. Likewise, the external force that intricates these elements with one another is outside of the individual elements control or prediction. Viscous Mixtures Unlike an architecture of contradictions, superpositions and accidental collisions, pliant systems are capable of engendering 36 ARCHITECTURAL CURVILINEARITY unpH'dicted connections with contextual, cultural, program- nutl ito, structural and economic contingencies by vicissitude. Vldssitude is often equated with vacillation, weakness8 and Intll'l'isiveness but more importantly these characteristics are trt'(IUcntly in the service of a tactical cunning.9 Vicissitude is • (IUality of being mutable or changeable in response to both '.vourable and unfavourable situations that occur by chance. Vldssitudinous events result from events that are neither arbi- trAry nor predictable but seem to be accidental. These events .rt' made possible by a collision of internal motivations with ""Il'rnal forces. For instance, when an accident occurs the vl"1 i m s immediately identify the forces contributing to the acci-

- 40. dt'1l1 and begin to assign blame. It is inevitable however, that nu single element can be made responsible for any accident ." I hese events occur by vicissitude; a confluence of particular Inlluences at a particular time makes the outcome of an acci- d('111 possible. If any element participating in such a confluence (If local forces is altered the nature of the event will change. In A Thousand Plateaus, Spinoza's concept of "a thousand vicis- alludes" is linked with Gregory Bateson's "continuing plateau uf intensity" to describe events which incorporate unpredict- "hie events through intensity. These occurrences are difficult to ICIl'alise, difficult to identify. 10 Any logic of vicissitude is depen- tll'nt on both an intrication of local intensities and the exegetic prcssure exerted on those elements by external contingencies, Nl'ither the intrications nor the forces which put them into rela- lion are predictable from within any single system. Connections hy vicissitude develop identity through the exploitation of local iltljacencies and their affiliation with external forces. In this fil'nse, vicissitudinous mixtures become cohesive through a log-ic ofviscosity. Viscous fluids develop internal stability in direct propor- lion to the external pressures exerted upon them. These fluids GREG LYNN 37

- 41. behave with two types of viscidity. They exhibit both internal cohesion and adhesion to external elements as their viscosity increases. Viscous fluids begin to behave less like liquids and more like sticky solids as the pressures upon them intensify. Similarly, viscous solids are capable of yielding continually under stress so as not to shear. Viscous space would exhibit a related cohesive stabil- ity in response to adjacent pressures and a stickiness or adhesion to adjacent elements. Viscous relations such as these are not reducible to any single or holistic organisation. Forms of viscosity and pliability cannot be examined outside of the vicissitudinous connections and forces with which their defor- mation is intensively involved. The nature of pliant forms is that they are sticky and flexible. Things tend to adhere to them. As pliant forms are manipulated and deformed the things that stick to their surfaces become incorporated within their interiors. Curving Away from Deconstructivism Along with a group of younger architects, the projects that best represent pliancy, not coincidentally, are being produced by many of the same architects previously involved in the valorisa- tion of contradictions. Deconstructivism theorised the world as a site of differences in order that architecture could represent these contradictions in form. This contradictory logic is begin- ning to soften in order to exploit more fully the particularities of urban and cultural contexts. This is a reasonable transition, as the Deconstructivists originated their projects with the inter- nal discontinuities they uncovered within buildings and sites. These same architects are beginning to employ urban strategies which exploit discontinuities, not by representing them in for- mal collisions, but by affiliating them with one another though continuous flexible systems.

- 42. 38 ARCHITECTURAL CURVILINEARITY Just as many of these architects have already been inscribed ...hl" a Deconstructivist style of diagonal forms, there will .",1), hc those who would enclose their present work within • Nto-Baroque or even Expressionist style of curved forms. "JW("vcr, many of the formal similitudes suggest a far richer *kJJCil' of curvilinearity"11 that can be characterised by the Involvement of outside forces in the development of form. If Inltrnally motivated and homogeneous systems were to extend In .tmight lines, curvilinear developments would result from the IIM'urporation of external influences. Curvilinearity can put into ..hllion the collected projects in this publication [Architectural ,"',ign 63], Deleuze's The Fold: Leibniz and the Baroque and Rene Tholn's catastrophe diagrams. The smooth spaces described by these continuous yet differentiated systems result from cur- ..linear sensibilities that are capable of complex deformations In rl'sponse to programmatic, structural, economic, aesthetic, political and contextual influences. This is not to imply that Intl'nsive curvature is more politically correct than an unin- volved formal logic, but rather, that a cunning pliability is often Inure effective through smooth incorporation than contradic- lion and conflict. Many cunning tactics are aggressive in nature. Whether insidious or ameliorative these kinds of cunning con- IIt'ctions discover new possibilities for organisation. A logic of rurvilinearity argues for an active involvement with external ('wnts in the folding, bending and curving of form. Already in several Deconstructivist projects are latent sug- J(estions of smooth mixture and curvature. For instance, the (iehry House is typically portrayed as representing materials Hnd forms already present within, yet repressed by, the subur- hlln neighbourhood: sheds, chain-link fences, exposed plywood, trailers, boats and recreational vehicles. The house is described

- 43. liS an "essay on the convoluted relationship between the conflict within and between forms ... which were not imported to but GREG LYNN 39 emerged from within the house."" The house is seen to provoke conflict within the neighbourhood due to its public representa- tion of hidden aspects of its context. The Gehry House violates the neighbourhood from within. Despite the dominant appeal of the house to contradictions, a less contradictory and more pliant reading of the house is possible as a new organisation emerges between the existing house and Gehry's addition. A dynamic stability develops with the mixing of the original and the addition. Despite the contradictions between elements pos- sible points of connection are exploited. Rather than valorise the conflicts the house engenders, as has been done in both academic and popular publications, a more pliant logic would identify, not the degree ofviolation, but the degree to which new connections were exploited. A new intermediate organisation occurs in the Gehry House by vicissitude from the affiliation of the existing house and its addition. Within the discontinuities of Deconstructivism there are inevitable unforeseen moments of cohesion. Similarly, Peter Eisenman's Wexner Center is convention- ally portrayed as a collision of the conflicting geometries of the campus, city and armoury which once stood adjacent to the site. These contradictions are represented by the diagonal collisions between the two grids and the masonry towers. Despite the dis- junctions and discontinuities between these three disparate systems, Eisenman's project has suggested recessive readings ofcontinuous non-linear systems ofconnection. Robert Somop3

- 44. identifies such a system of Deleuzian rhizomatous connections between armoury and grid. The armoury and diagonal grids are shown by Somol to participate in a hybrid L-movement that organises the main gallery space. Somol's schizophrenic analy- sis is made possible by, yet does not emanate from within, a Deconstructivist logic of contradiction and conflict. The force of this Deleuzian schizo-analytic model is its ability to maintain 40 . ARCHITECTURAL CURVILINEARITY multiple organisations simultaneously. In Eisenman's project Iht' tower and grid need not be seen as mutually exclusive or in (,()lItradiction. Rather, these disparate elements may be seen I" distinct elements co-present within a composite mixture. I%mcy does not result from and is not in line with the previous luc:hitecturallogic of contradiction, yet it is capable of exploit- Ing many conflicting combinations for the possible connections Ihilt are overlooked. Where DeconstructivistArchitecture was seen II) t'xploit external forces in the familiar name of contradiction And conflict, recent pliant projects by many of these architects t'xhibit a more fluid logic of connectivity. Immersed in Context The contradictory architecture of the last two decades has t'volved primarily from highly differentiated, heterogeneous ('ClI1texts within which conflicting, contradictory and discon- Iinuous buildings were sited. An alternative involvement with Iwterogeneous contexts could be affiliated, compliant and con- Iinuous. Where complexity and contradiction arose previously (rom inherent contextual conflicts, present attempts are being made to fold smoothly specific locations, materials and pro- Jtmmmes into architecture while maintaining their individual Idt'ntity.

- 45. This recent work may be described as being compliant; in II state of being plied by forces beyond control. The projects are folded, pliant and supple in order to incorporate their nmtexts with minimal resistance. Again, this characterisation lihould not imply flaccidity but a cunning submissiveness that Is l'apable of bending rather than breaking. Compliant tactics, Mll'h as these, assume neither an absolute coherence nor cohe- ,.ion between discrete elements but a system of provisional, Intl'nsive, local connections between free elements. Intensity d{'scribes the dynamic internalisation and incorporation of GREG lYNN 41 external influences into a pliant system. Distinct from a whole organism-to which nothing can be added or subtracted- intensive organisations continually invite external influence within their internal limits so that they might extend their influence through the affiliations they make. A two-fold deter- ritorialisation, such as this, expands by internalising external forces. This expansion through incorporation is an urban alternative to either the infinite extension of International Modernism, the uniform fabric of Contextualism or the con- flicts of Post-Modernism and Deconstructivism. Folded, pliant and supple architectural forms invite exigencies and contingen- cies in both their deformation and their reception. In both Learning from Las Vegas and Deconstructivist Architecture, urban contexts provided rich sites of difference. These differences are presently being exploited for their abil- ity to engender multiple lines of local connections rather than lines of conflict. These affiliations are not predictable by any contextual orders but occur by vicissitude. Here, urban fabric

- 46. has no value or meaning beyond the connections that are made within it. Distinct from earlier urban sensibilities that general- ised broad formal codes, the collected projects develop local, fine grain, complex systems of intrication. There is no general urban strategy common to these projects, only a kind of tactical mutability. These folded, pliant and supple forms of urbanism are neither in deference to nor in defiance of their contexts but exploit them by turning them within their own twisted and curvilinear logics. The Supple and Curvilinear 1 suppleadj [ME souple, fr OF, fr L supplic-, supplex submissive, suppliant, lit, bending under, fr sub +plic- (akin to plicare to fold)-more at PLY] u: compliant often 42 . ARCHITECTURAL CURVILINEARITY to the point of obsequiousness b: readily adaptable or responsive to new situations 2a: capable of being bent or folded without creases, cracks or breaks: PLIANT b: able to perform bending or twisting movements with ease and grace: LIMBER c: easy and fluent without stiffness or awkwardness. 14 At an urban scale, many of these projects seem to be some- where between contextualism and expressionism. Their supple rorms are neither geometrically exact nor arbitrarily figural. I:or example, the curvilinear figures of Shoei Yoh's roof struc-

- 47. tures are anything but decorative but also resist being reduced to a pure geometric figure. Yoh's supple roof structures exhibit /I logic of curvilinearity as they are continuously differentiated Ill'cording to contingencies. The exigencies of structural span Il'ngths, beam depths, lighting, lateral loading, ceiling height lind view angles influence the form of the roof structure. Rather than averaging these requirements within a mean or mini- mum dimension they are precisely maintained by an anexact ),l·t rigorous geometry. Exact geometries are eidetic; they can bl' reproduced identically at any time by anyone. In this regard, they must be capable of being reduced to fixed mathematical (Iuantities. Inexact geometries lack the precision and rigor nec- t'ssary for measurement. Anexact geometries, as described by Edmund Husserl,15 nrc those geometries which are irreducible yet rigorous. These geometries can be determined with precision yet cannot be reduced to average points or dimensions. Anexact geometries often appear to be merely figural in this regard. Unlike exact geometries, it is meaningless to repeat identically an anexact geometric figure outside of the specific context within which It is situated. In this regard, anexact figures cannot be easily translated. GREG LYNN 43 http:awkwardness.14 Jeffrey Kipnis has argued convincingly that Peter Eisenman's Columbus Convention Center has become a canonical model for the negotiation of differentiated urban fringe sites through the use of near figures. '6 Kipnis identifies the disparate sys- tems informing the Columbus Convention Center including: a single volume of inviolate programme of a uniform shape

- 48. and height larger than two city blocks, an existing fine grain fabric of commercial buildings and a network of freeway inter- changes that plug into the gridded streets of the central business district. Eisenman's project drapes the large rectilinear vol- ume of the convention hall with a series of supple vermiforms. These elements become involved with the train tracks to the north-east, the highway to the south-east and the pedes- trian scale of High Street to the west. The project incorporates the multiple scales, programmes, and pedestrian and auto- motive circulation of a highly differentiated urban context. Kipnis' canonisation of a form which is involved with such spe- cific contextual and programmatic contingencies seems to be frustrated from the beginning. The effects of a pliant urban mix- ture such as this can only be evaluated by the connections that it makes. Outside of specific contexts, curvature ceases to be intensive. Where the Wexner Center, on the same street in the same city, represents a monumental collision, the Convention Center attempts to disappear by connection between intervals within its context; where the Wexner Center destabilises through contradictions the Convention Center does so by subterfuge. In a similar fashion Frank Gehry's Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain covers a series of orthogonal gallery spaces with flexible tubes which respond to the scales of the adjacent roadways, bridges, the Bilbao River and the existing medieval city. Akin to the Vitra Museum, the curvilinear roof forms of the Bilbao Guggenheim integrate the large rectilinear masses of 44 . ARCHITECTURAL CURVILINEARITY !Cullery and support space with the scale of the pedestrian and IlUtomotive contexts.

- 49. The unforeseen connections possible between differenti- illl'" sites and alien programmes require conciliatory, complicit, pliant, flexible and often cunning tactics. Presently, numerous IIrchitects are involving the heterogeneities, discontinuities and tli fferences inherent within any cultural and physical context by IIligning formal flexibility with economic, programmatic and Ii' ructural compliancy. A multitude ofpli based words-folded, pliant, supple, flexible, plaited, pleated, plicating, complicitous, t'Ompliant, complaisant, complicated, complex and multiplici- tous to name a few-can be invoked to describe this emerging urban sensibility of intensive connections. The Pliant and Bent pJiableadj [Me fr plieirto bend, fold-more at PLY] 1a: supple enough to bend freely or repeatedly without breaking b: yield- ing readily to others: COMPLAISANT 2: adjustable to varying conditions: ADAPTABLE, syn see PLASTIC, ant obstinate.17 John Rajchman, in reference to Gilles Deleuze's book Le pli has already articulated an affinity between complexity, or plex- words, and folding, or plic-words, in the Deleuzian paradigm of "perplexing plications" or "perplication.'"8 The plexed and the plied can be seen in a tight knot of complexity and pliancy. Plication involves the folding in ofexternal forces. Complication involves an intricate assembly of these extrinsic particularities into a complex network. In biology, complication is the act ofan embryo folding in upon itself as it becomes more complex. To become complicated is to be involved in mUltiple complex, intri- (.'ate connections. Where Post-Modernism and

- 50. Deconstructivism resolve external influences of programme, use, economy and GREG LYNN 45 http:obstinate.17 advertising through contradiction, compliancy involves these external forces by knotting, twisting, bending, and folding them within form. Pliant systems are easily bent, inclined or influenced. An anatomical "plica" is a single strand within multiple "plicae." It is a multiplicity in that it is both one and many simultane- ously. These elements are bent along with other elements into a composite, as in matted hair(s). Such a bending together of elements is an act ofmultiple plication or multiplication rather than mere addition. Plicature involves disparate elements with one another through various manipulations of bending, twist- ing, pleating, braiding, and weaving through external force. In RAA Um's Croton Aqueduct project a single line following the subterranean water supply for New York City is pulled through multiple disparate programmes which are adjacent to it and which cross it. These programmatic elements are braided and bent within the continuous line of recovered public space which stretches nearly twenty miles into Manhattan. In order to incor- porate these elements the line itself is deflected and reoriented, continually changing its character along its length. The seem- ingly singular line becomes populated by finer programmatic elements. The implications ofLe pli for architecture involve the proliferation of possible connections betweenfree entities such as these. A plexus is a multi-linear network of interweavings, inter- twinings and intrications; for instance, of nerves or blood

- 51. vessels. The complications of a plexus-what could best be called complexity-arise from its irreducibility to any single organisation. A plexus describes a multiplicity of local connec- tions within a single continuous system that remains open to new motions and fluctuations. Thus, a plexial event cannot occur at any discrete point. A multiply plexed system-a com- plex-cannot be reduced to mathematical exactitude, it must 46 ARCHITECTURAL CURVILINEARITY bet described with rigorous probability. Geometric systems have I distinct character once they have been plied; they exchange Axed co-ordinates for dynamic relations across surfaces. Alternative types of transformation I ,Iscounting the potential ofearlier geometric diagrams ofprob- Ibility, such as Buffon's Needle Problem,'9 D'Arcy Thompson provides perhaps the first geometric description of variable ddormation as an instance of discontinuous morphological development. His cartesian deformations, and their use of flex- Ible topological rubber sheet geometry, suggest an alternative to the static morphological transformations of autonomous architectural types. A comparison ofthe typological and trans- rormational systems of Thompson and Rowe illustrates two rlldically different conceptions of continuity. Rowe's is fixed, ('xact, striated, identical and static, where Thompson's is dynamic, anexact, smooth, differentiated and stable. Both Rudolf Wittkower-in his analysis of the Palladian villas of :194920-and Rowe-in his comparative analysis of Iltllladio and Le Corbusier of:194721-uncovera consistent organ- isational type: the nine-square grid. In Wittkower's analysis of twelve Palladian villas the particularities of each villa accumu- late (through what Edmund Husserl has termed variations) to