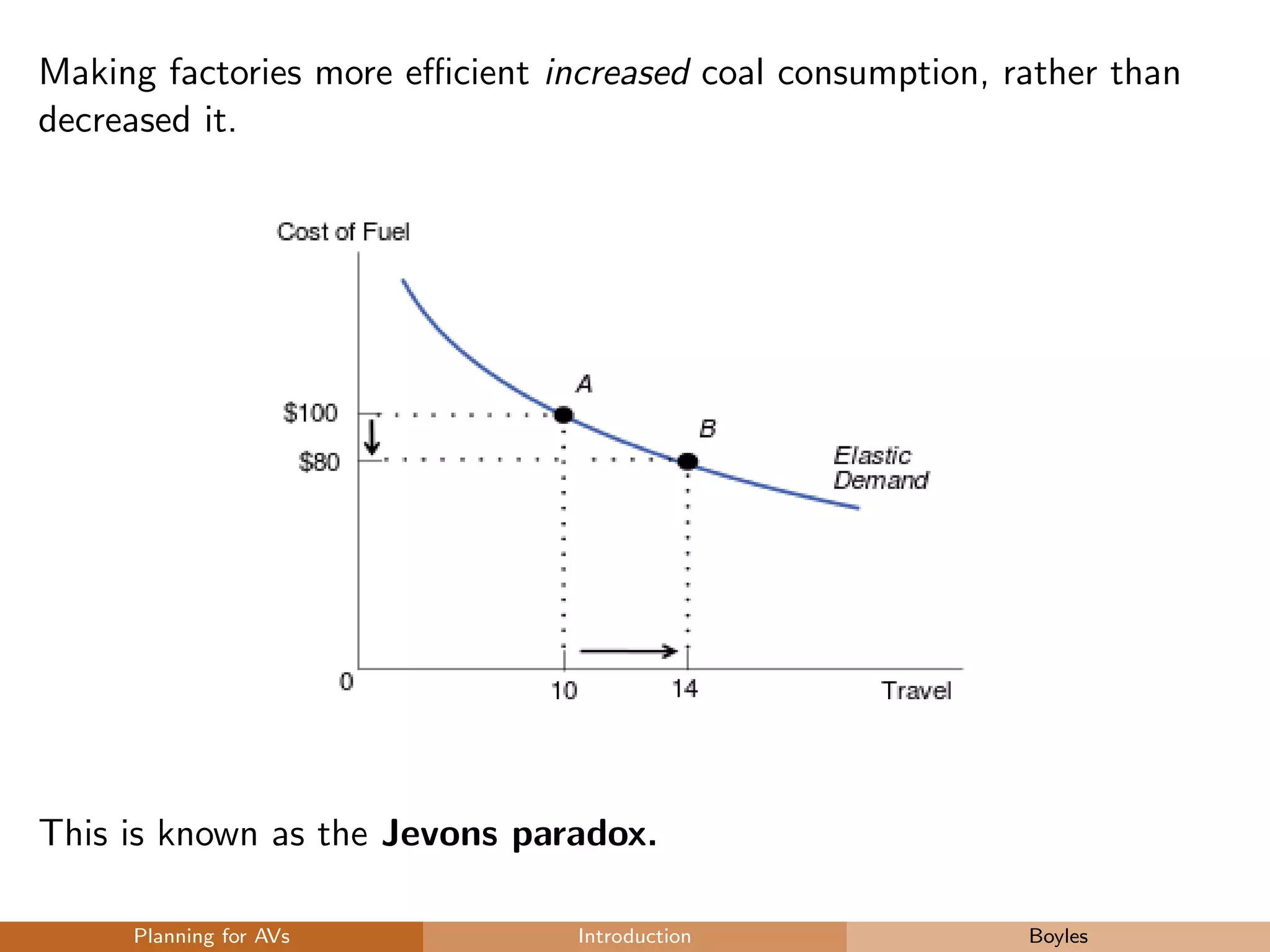

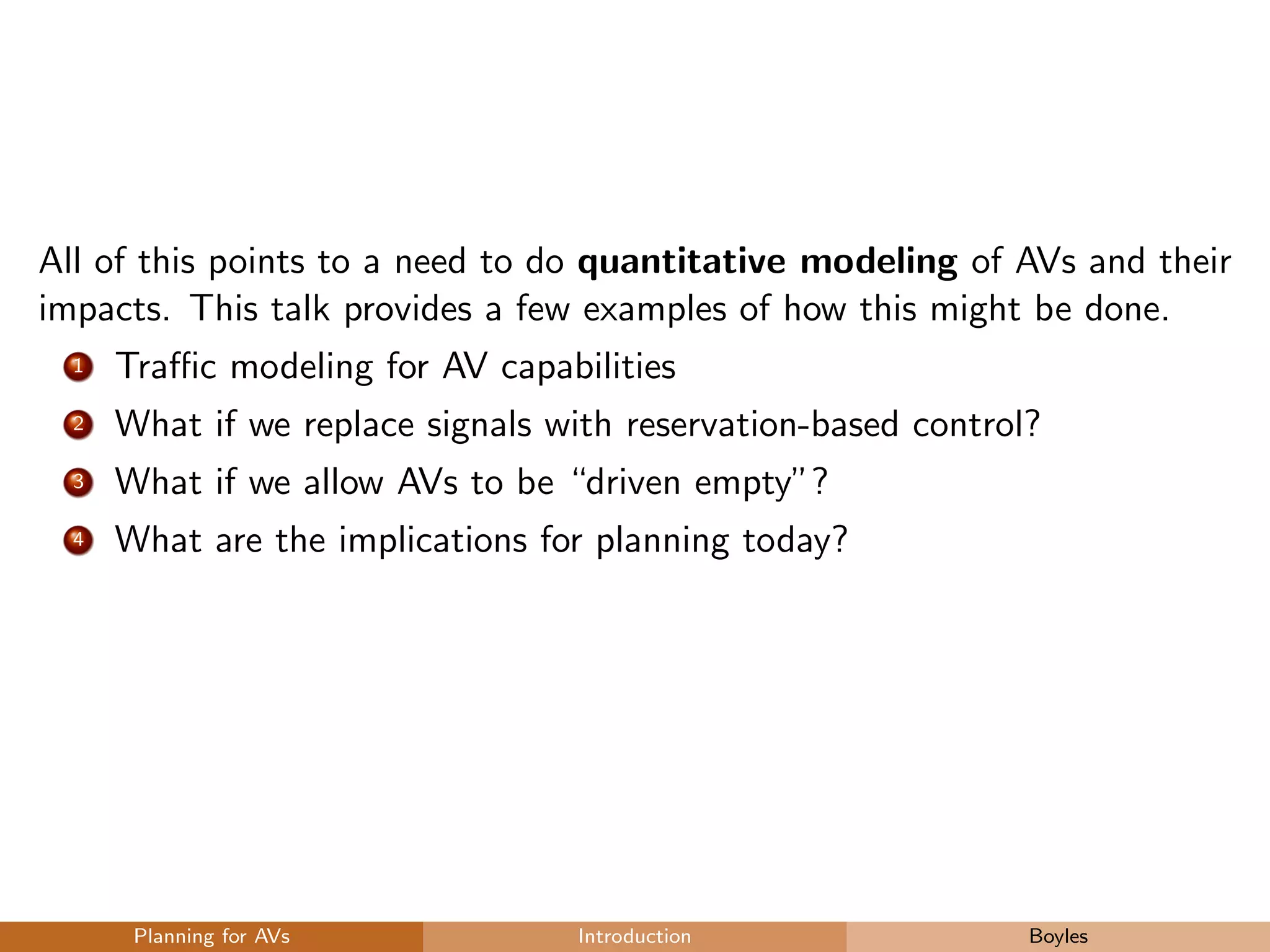

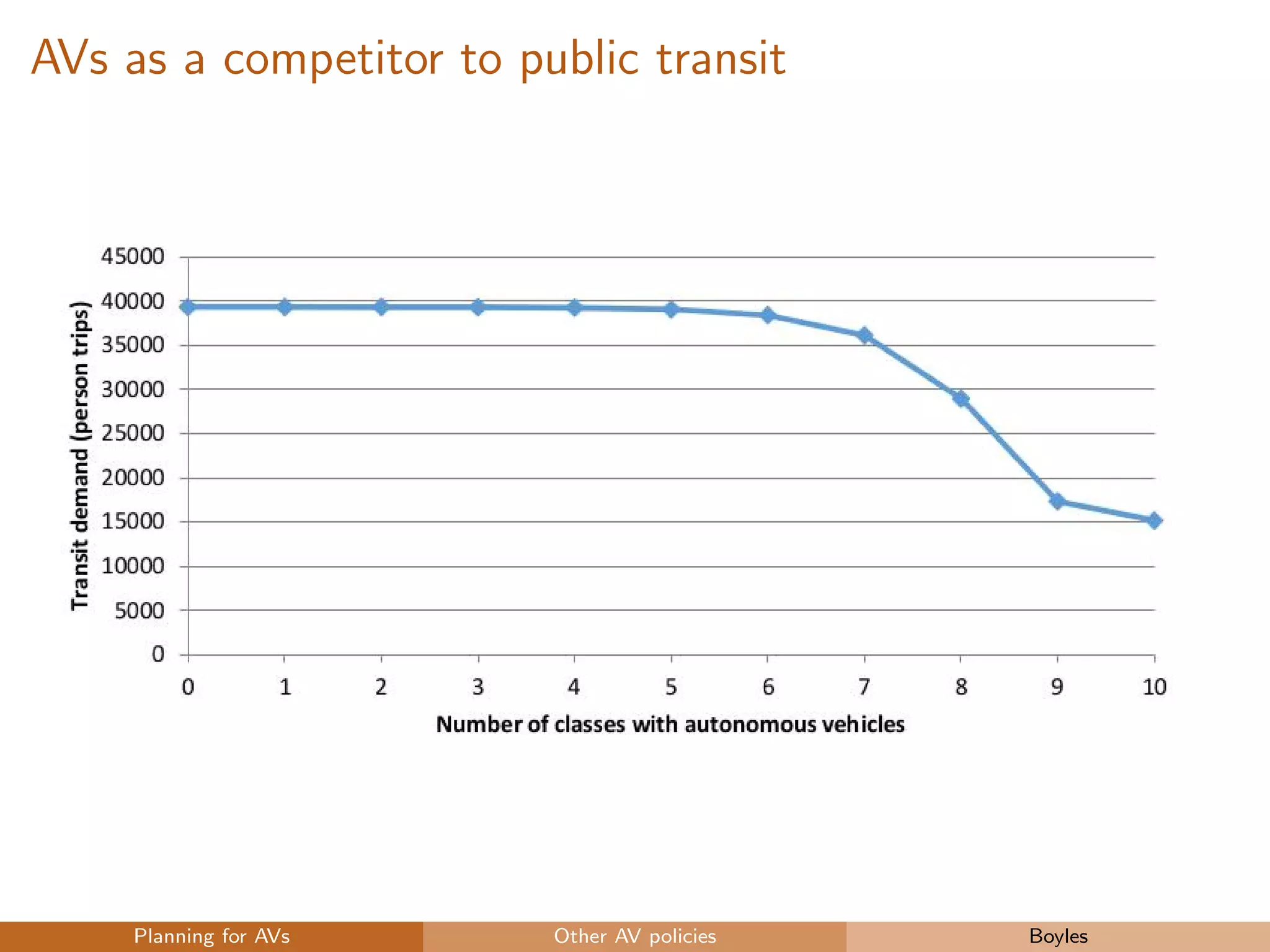

This document summarizes a presentation about planning for a world with connected and automated vehicles. Some key points include:

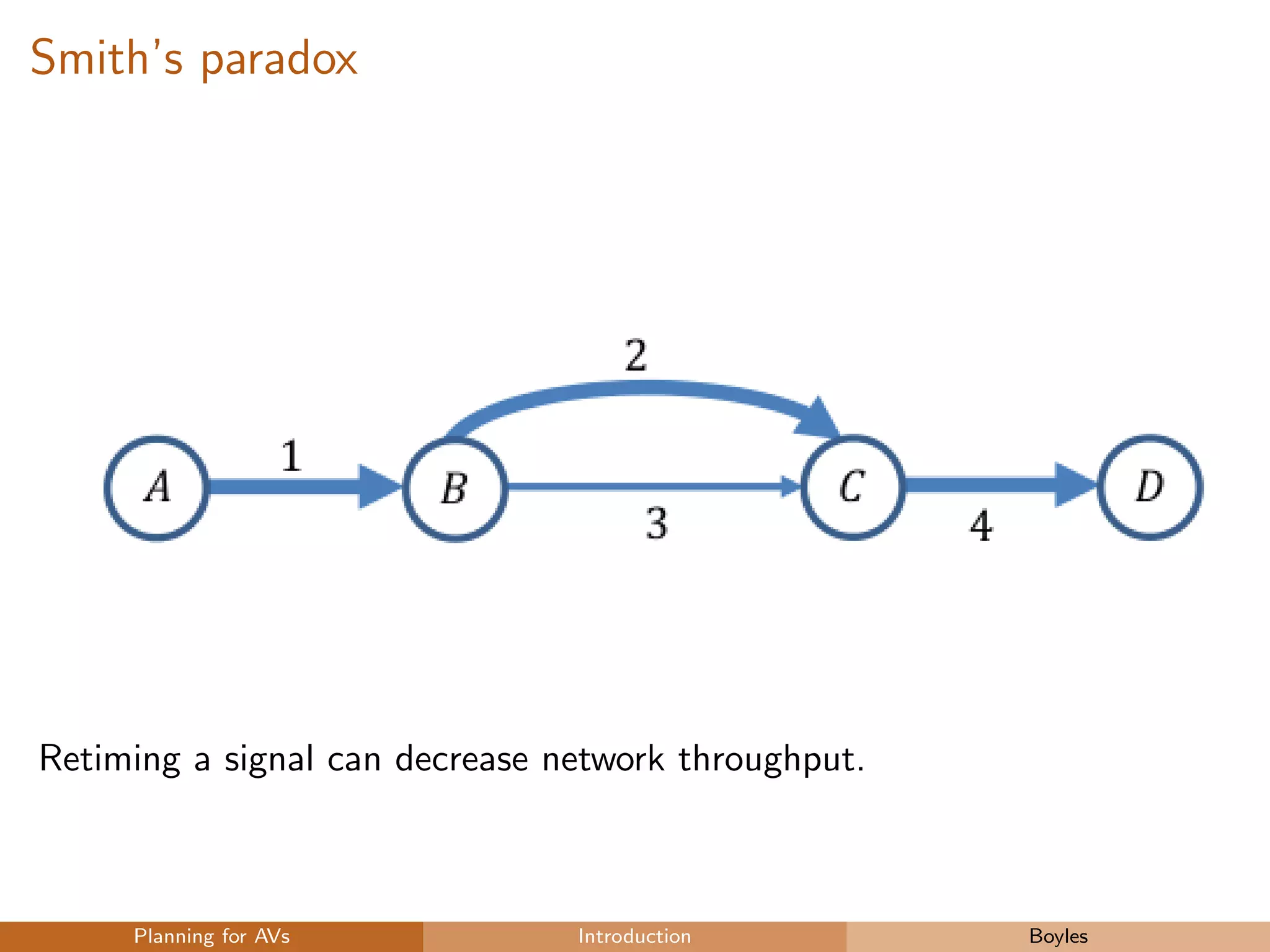

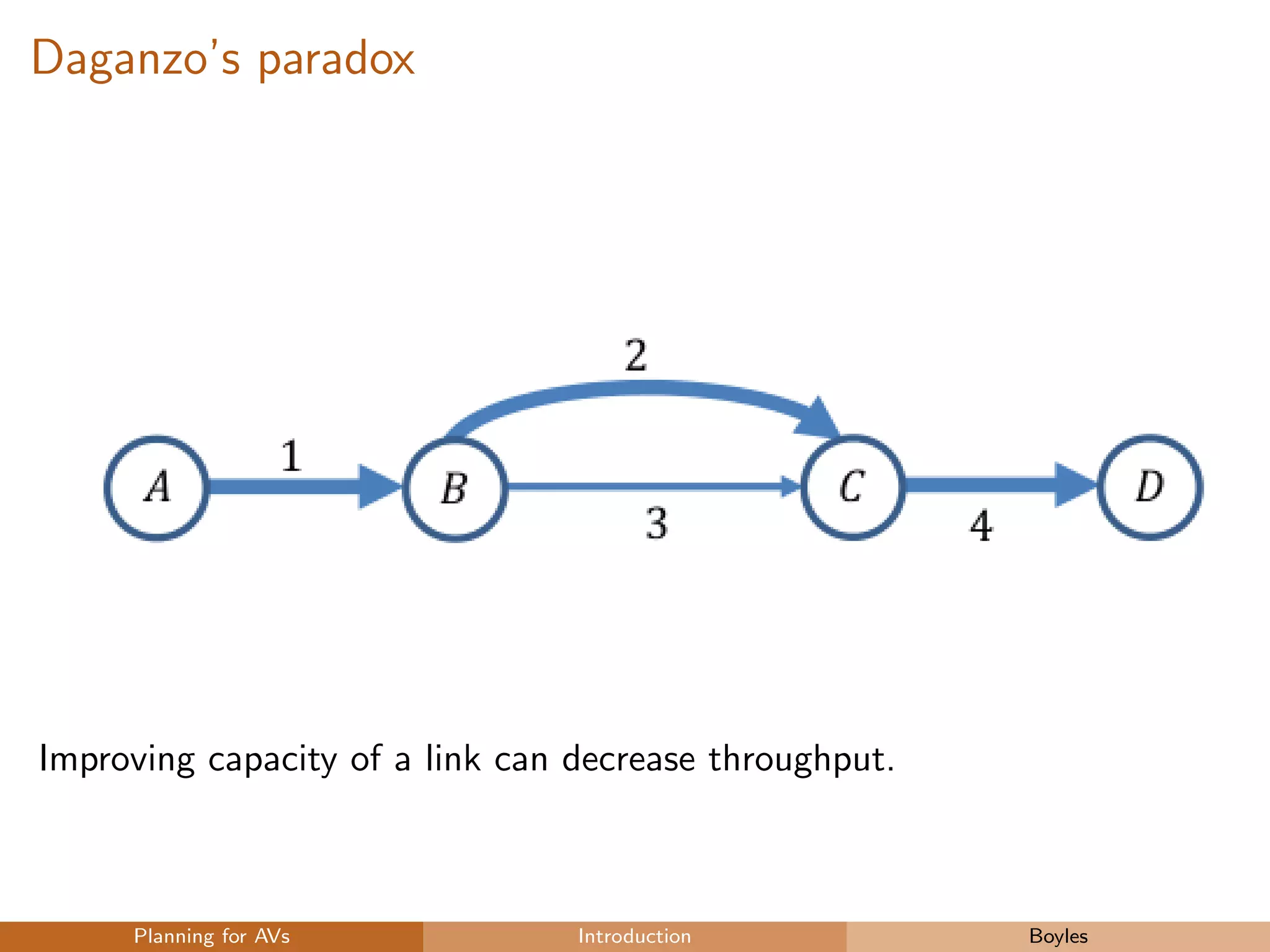

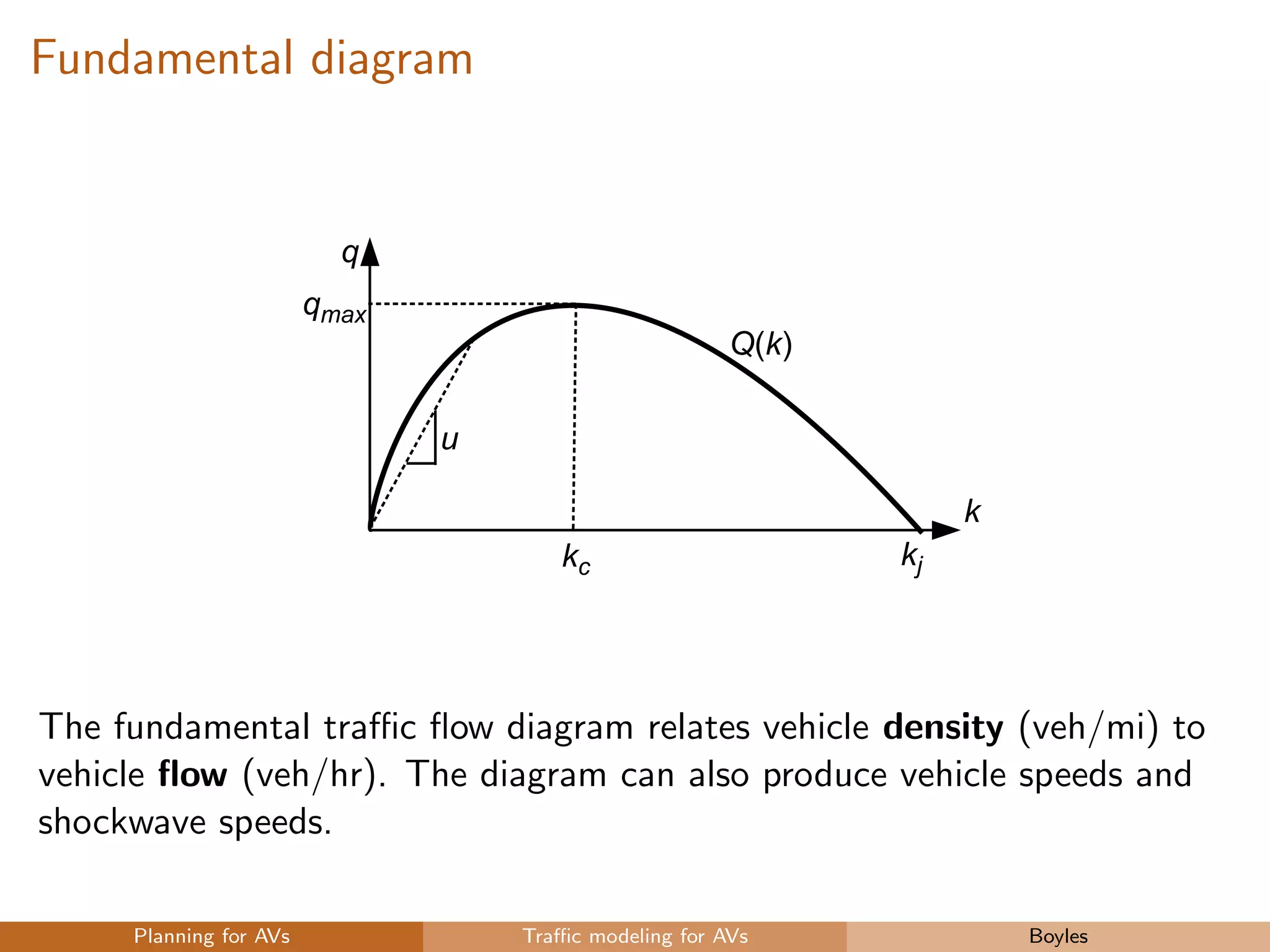

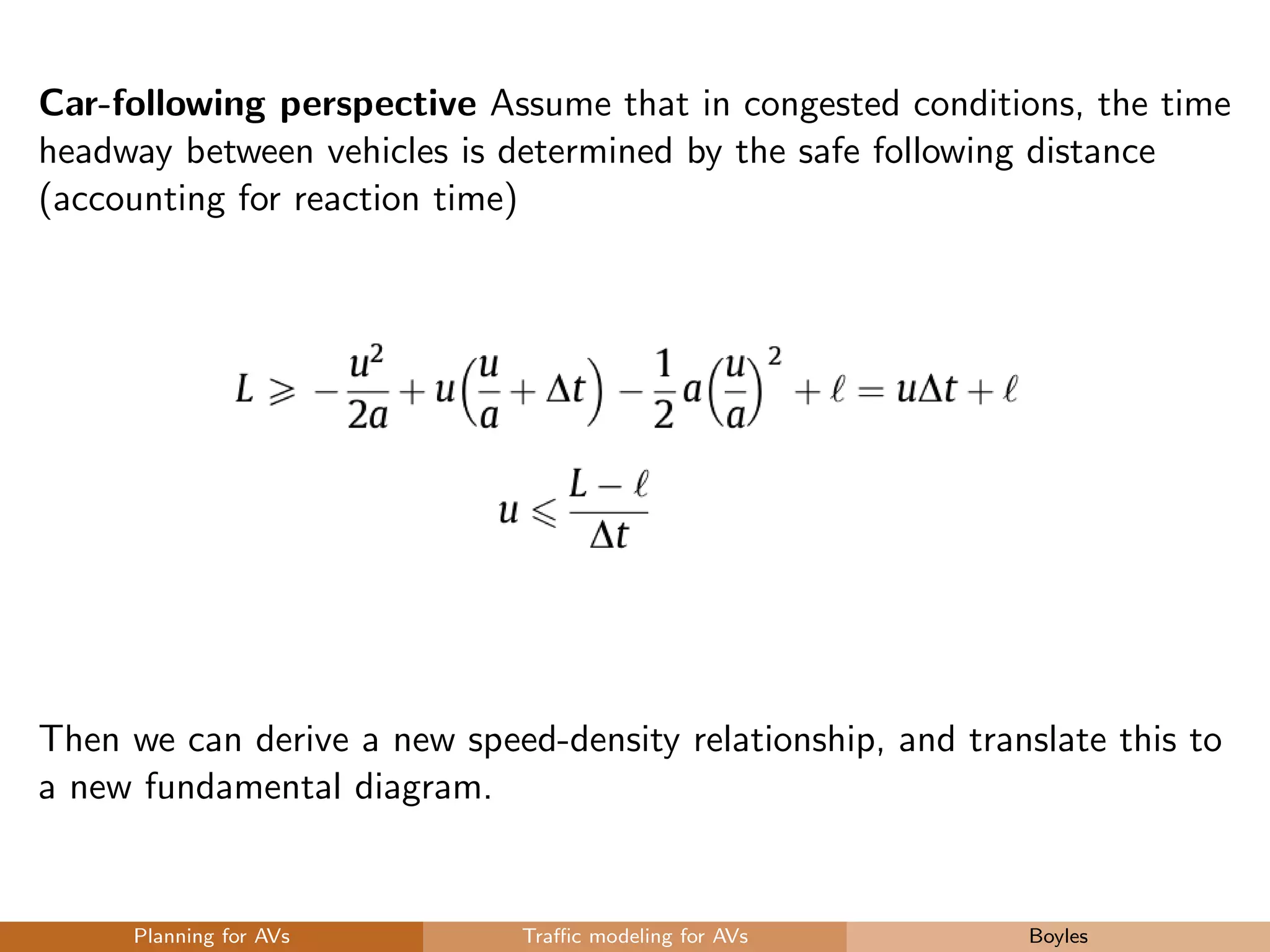

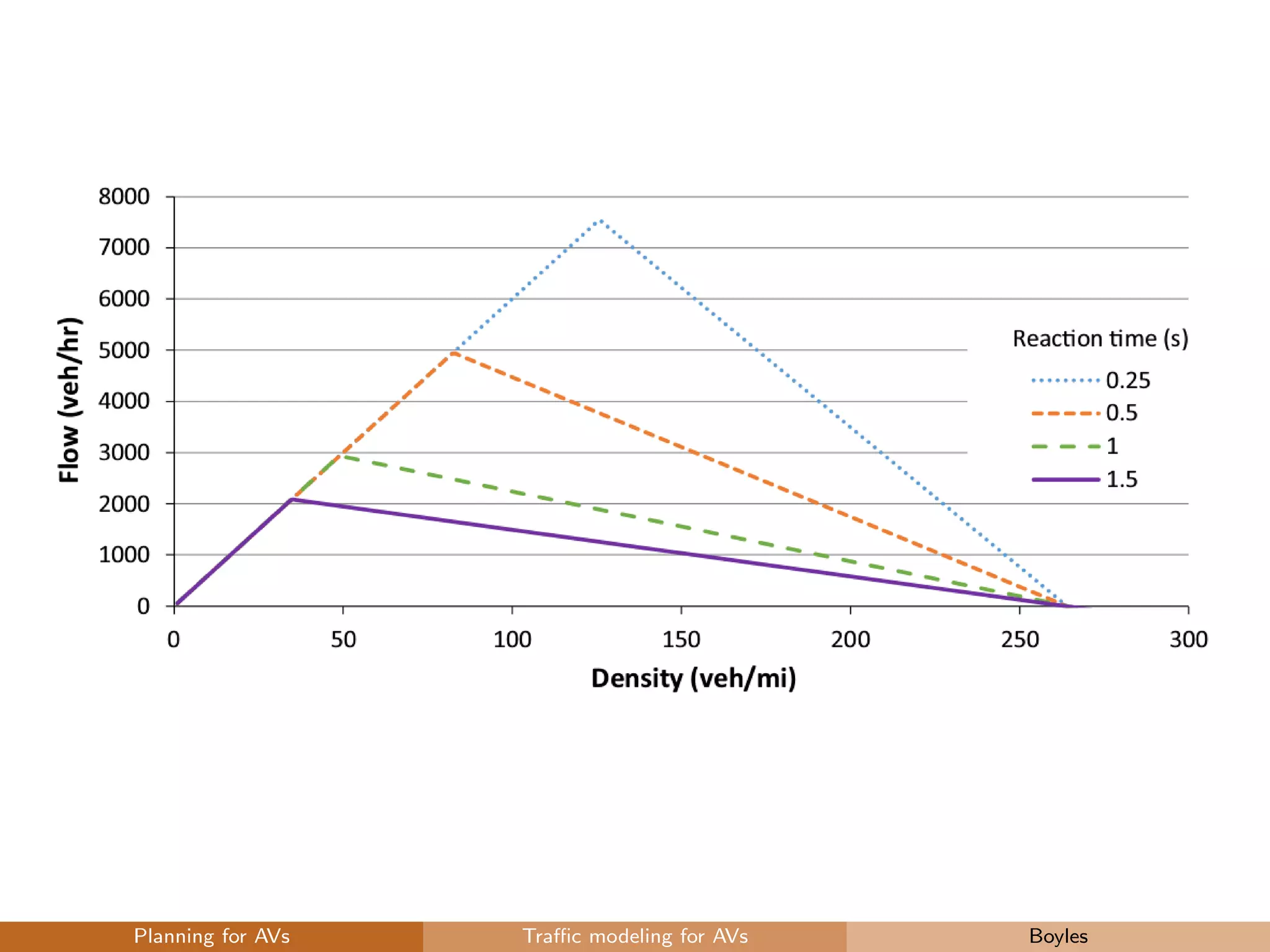

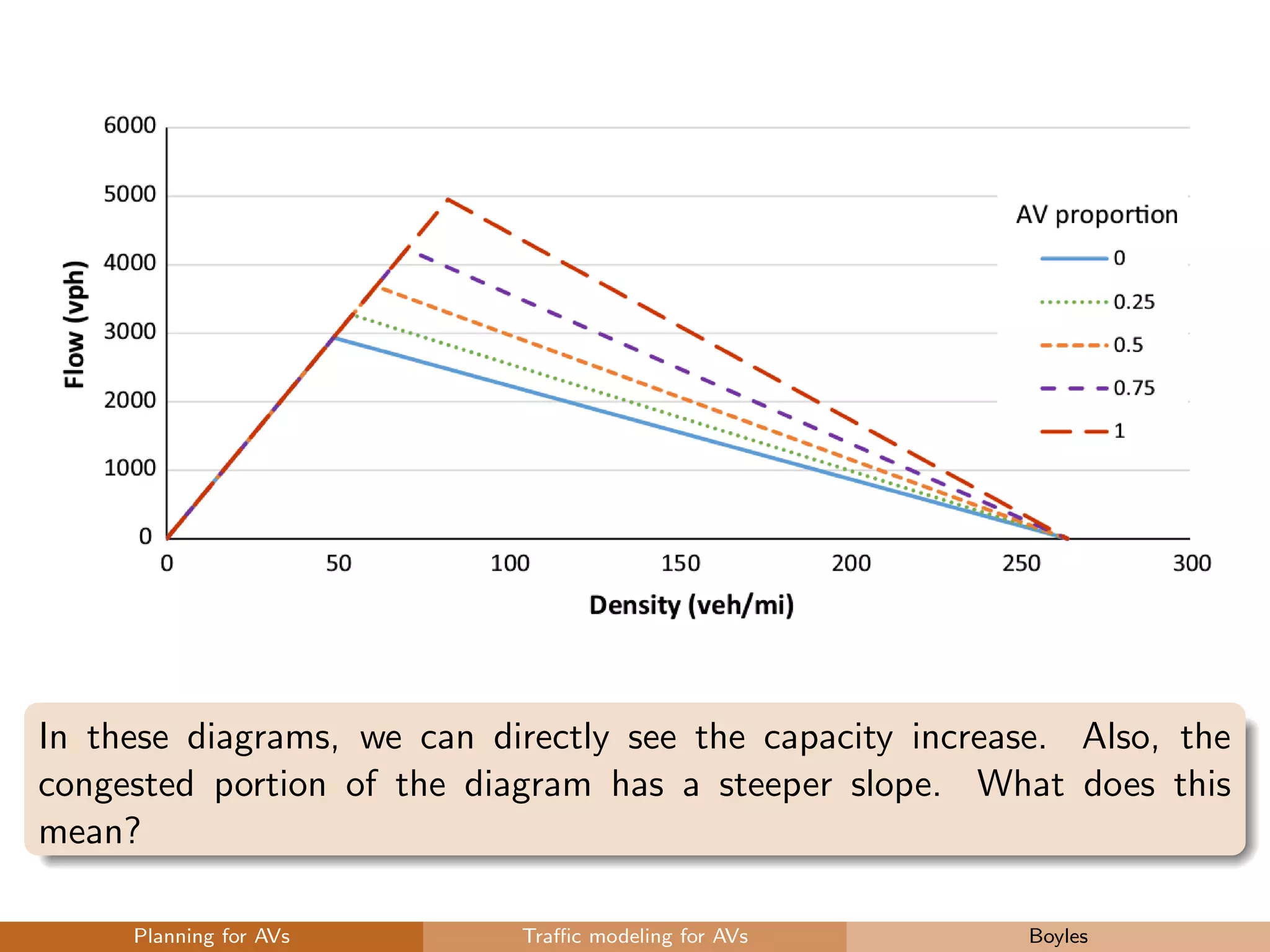

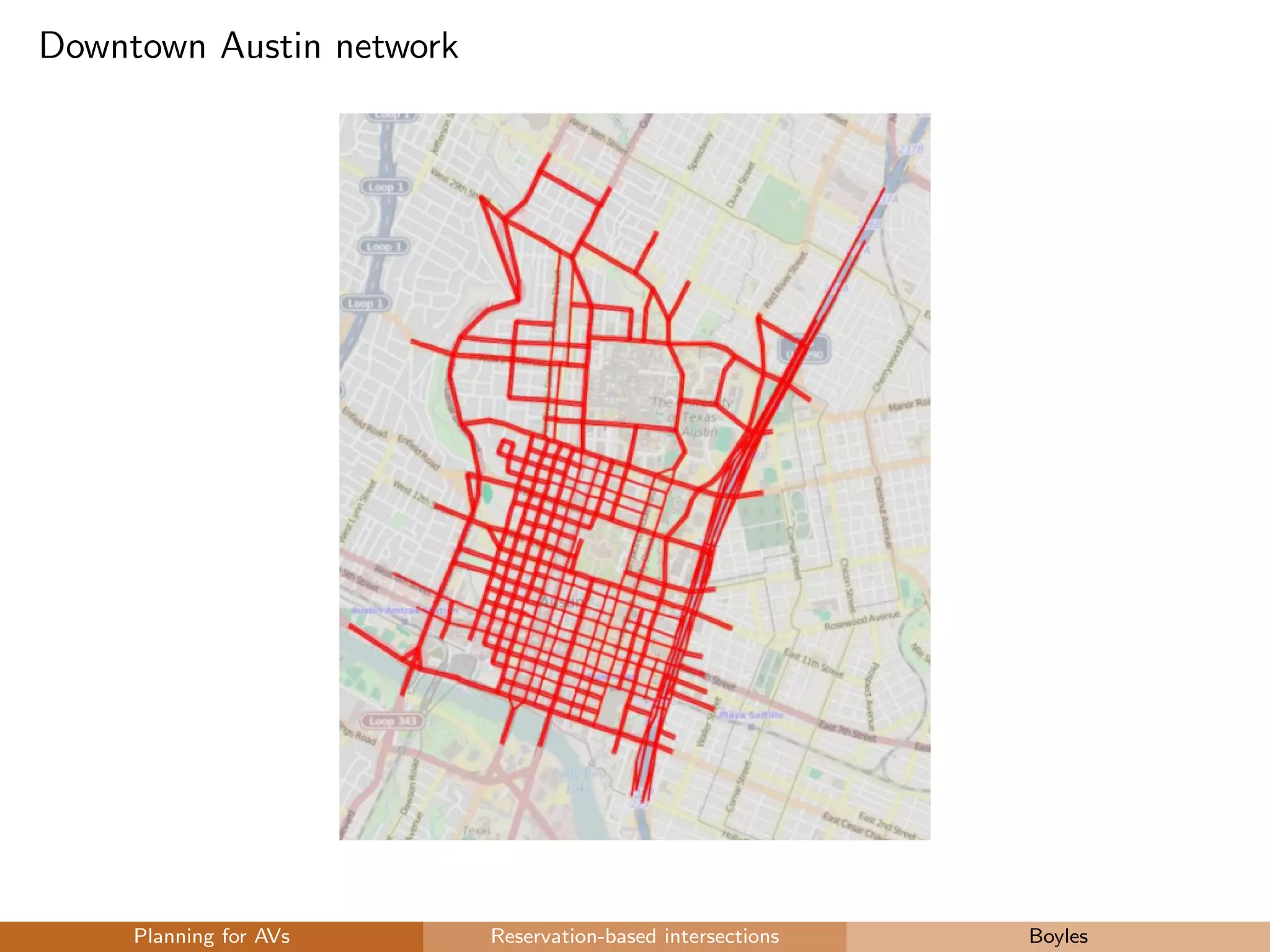

- Automated vehicles will have major impacts on traffic such as increased road capacity through platooning and new traffic control strategies.

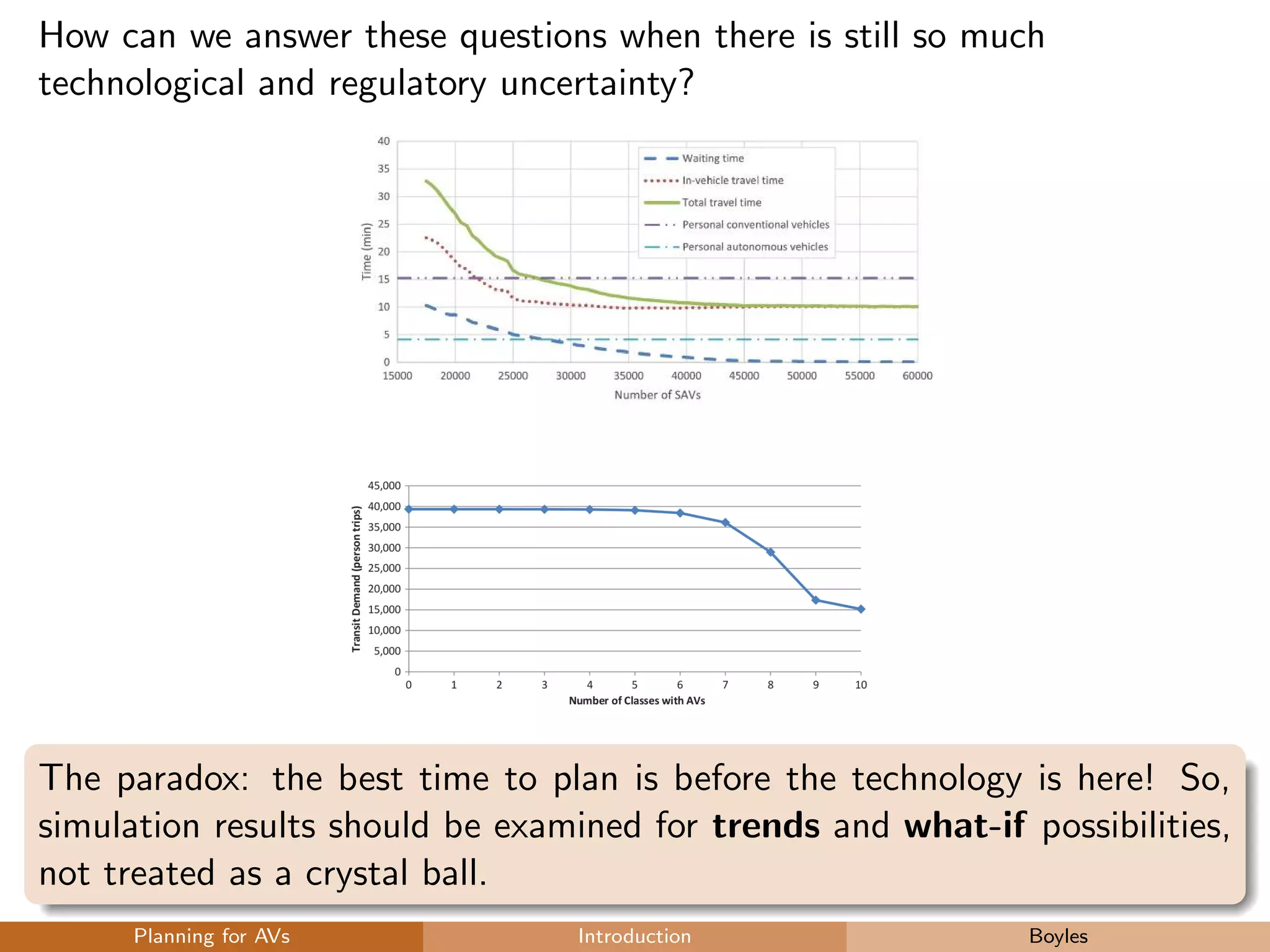

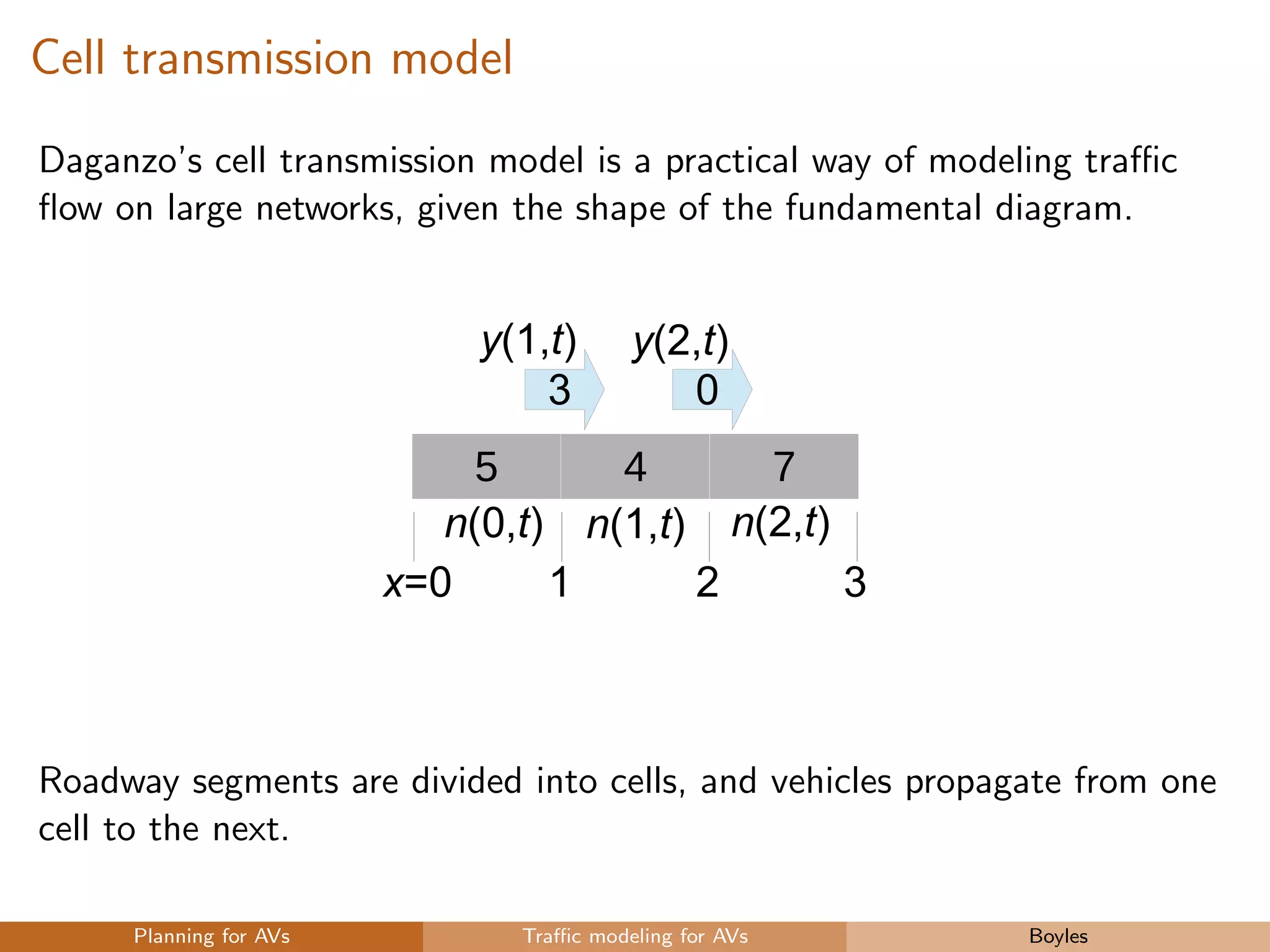

- Models are needed to simulate these impacts at large regional scales given technological and regulatory uncertainties.

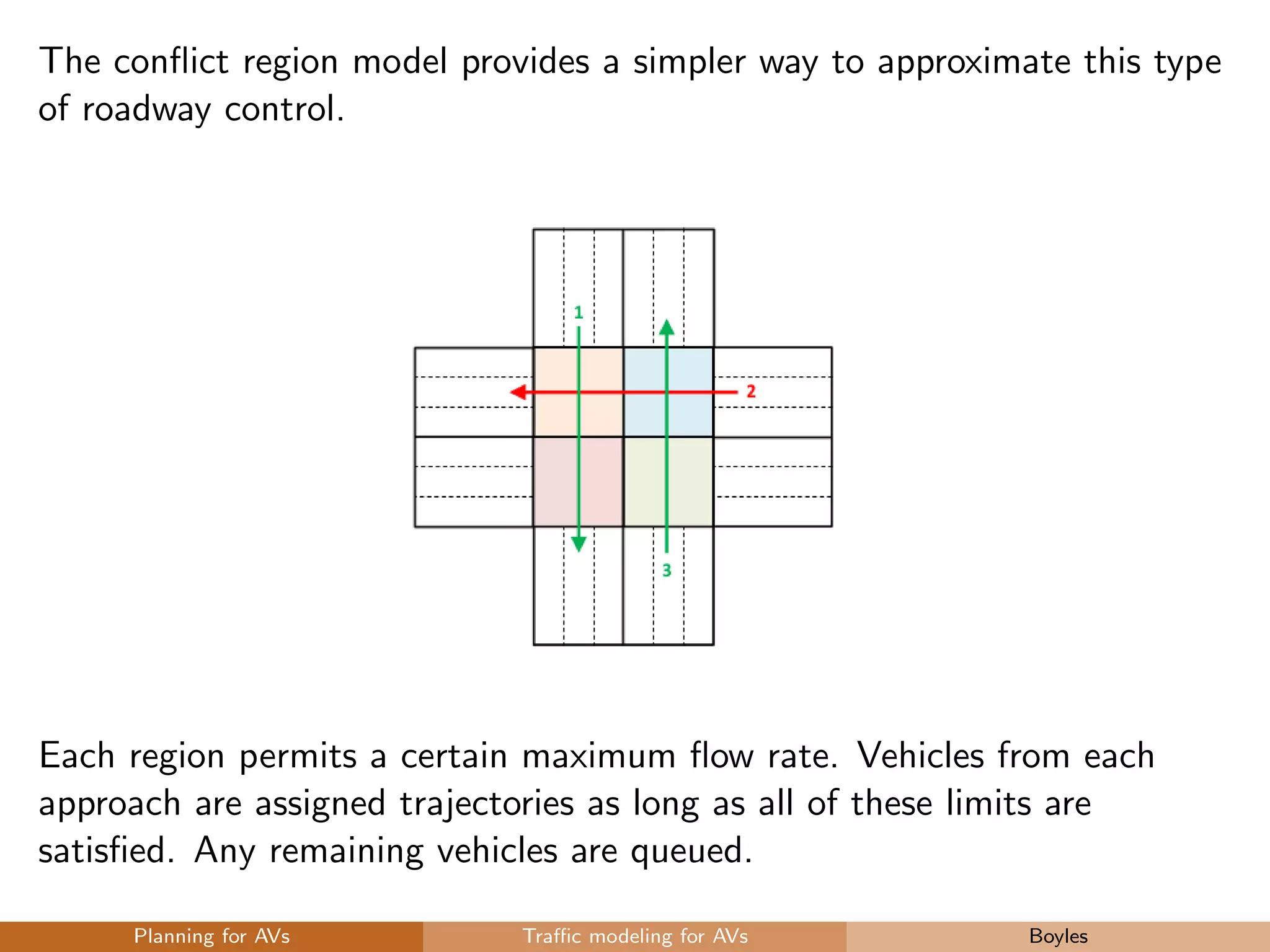

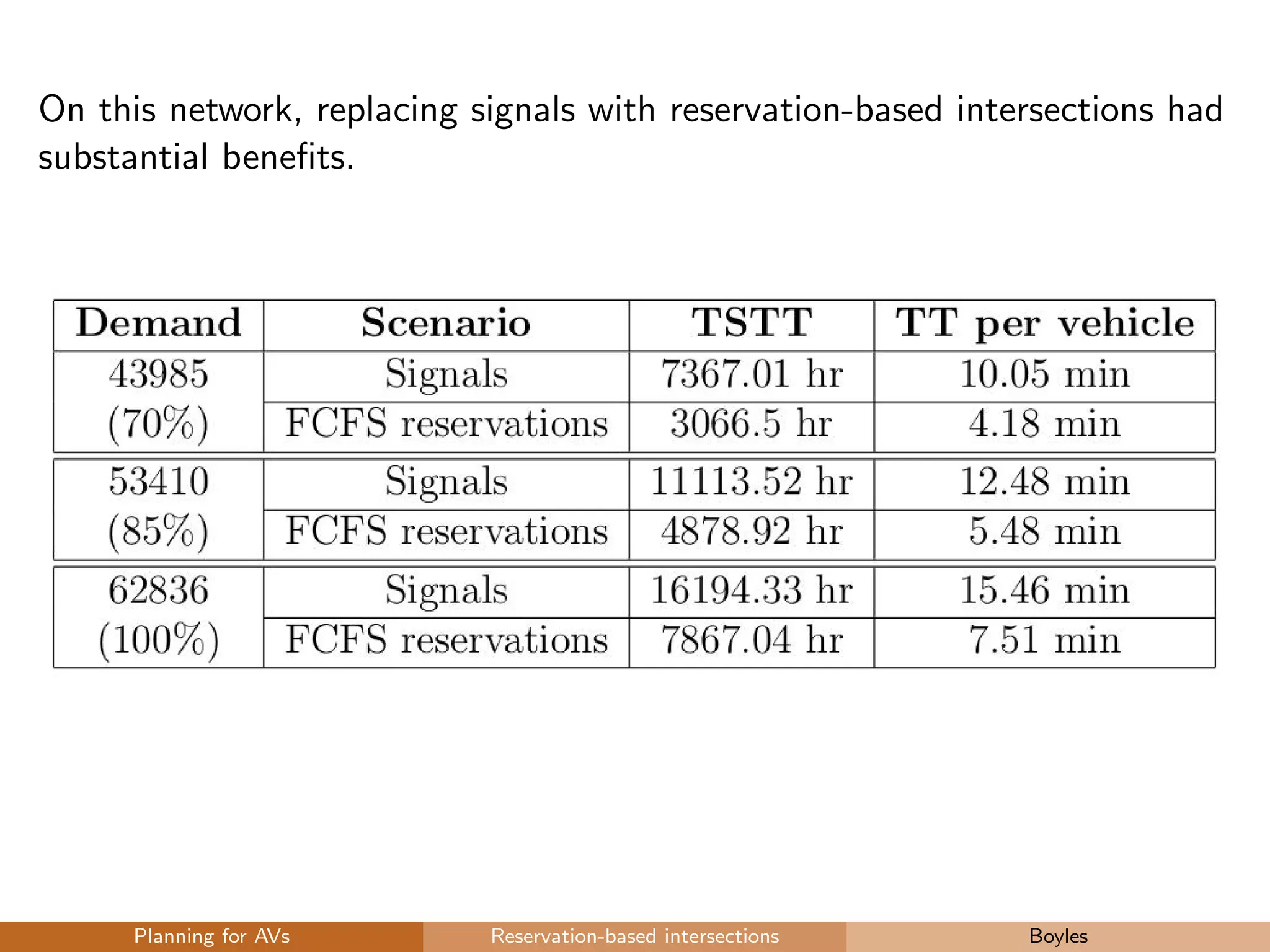

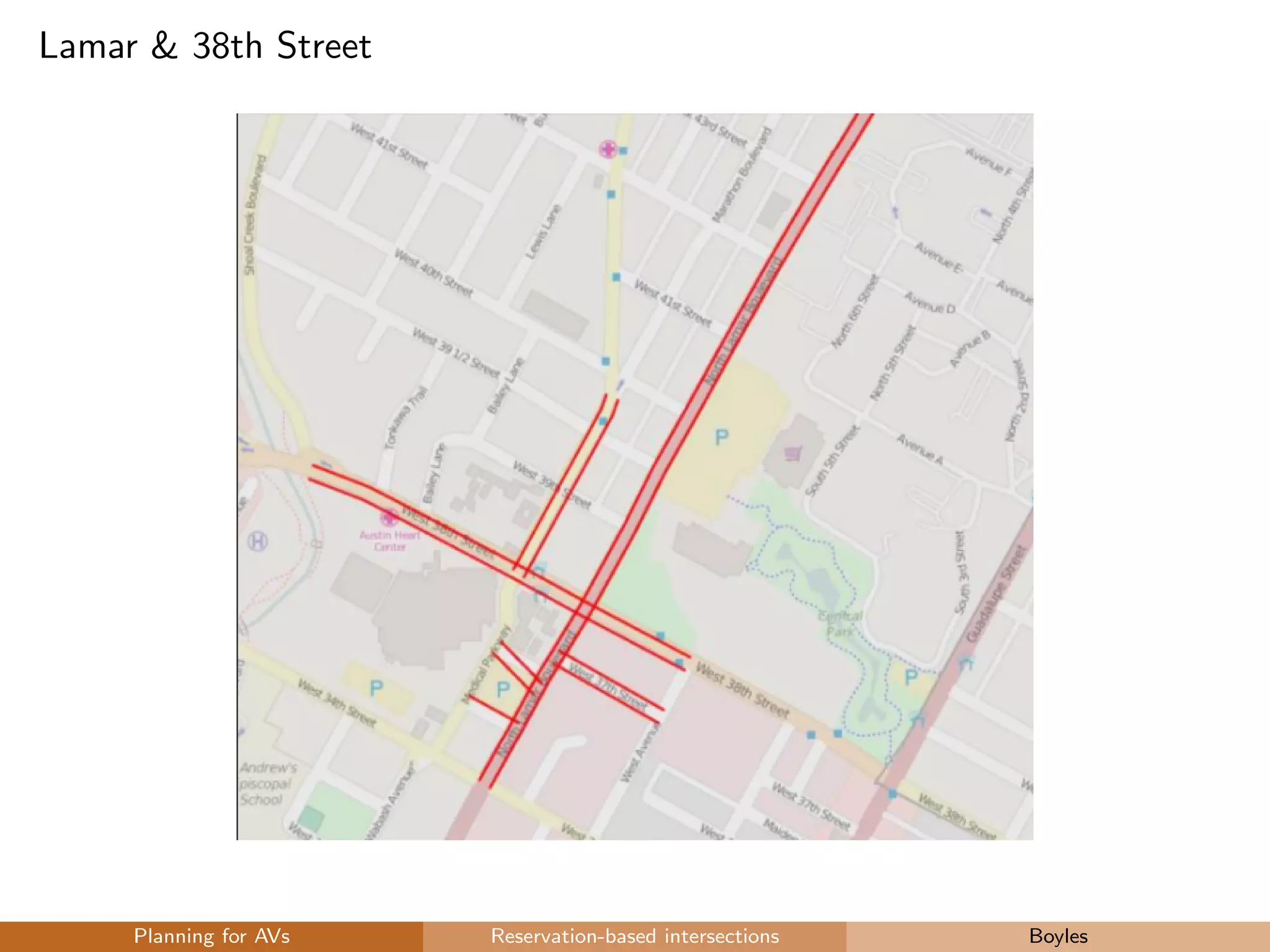

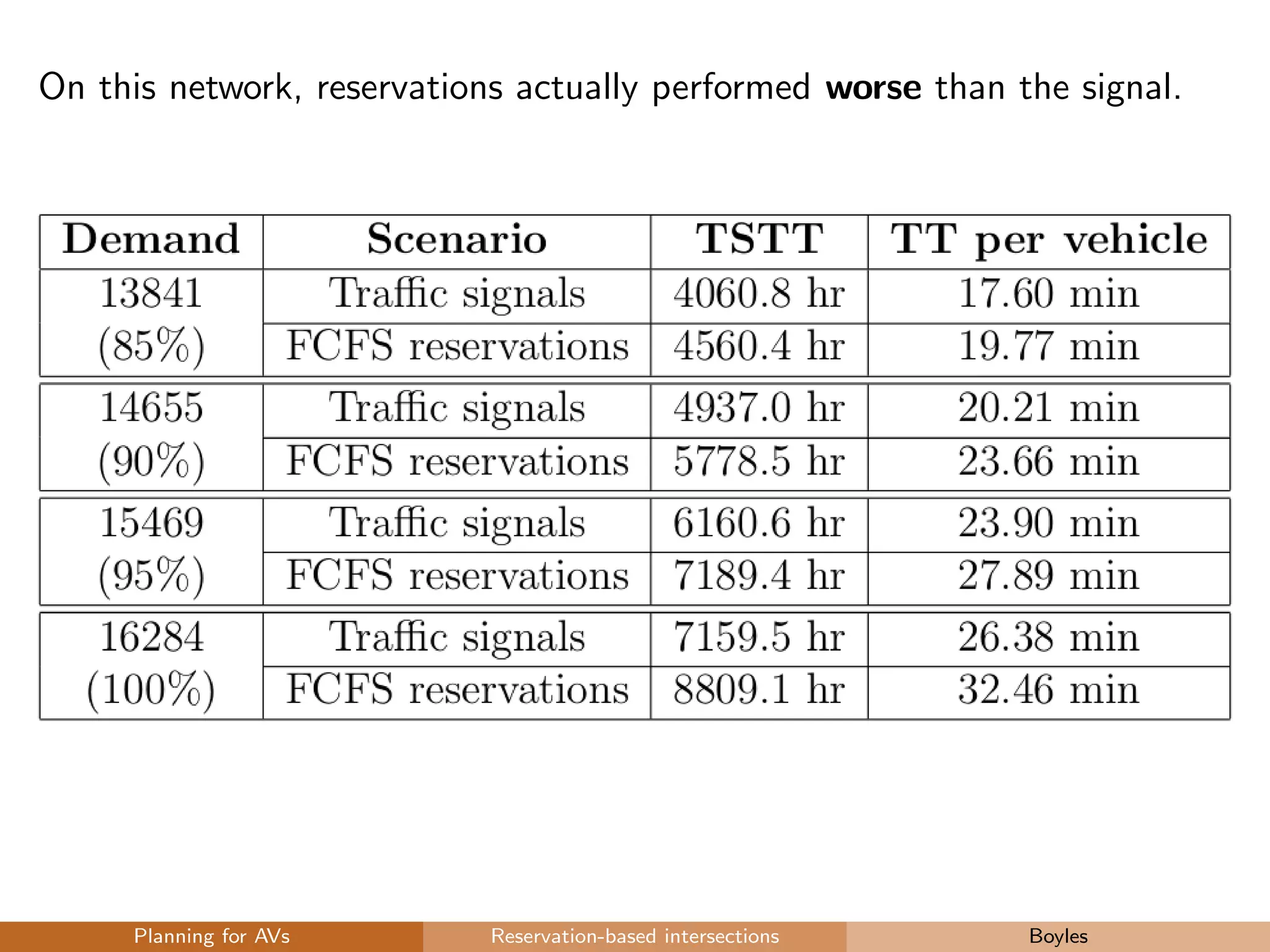

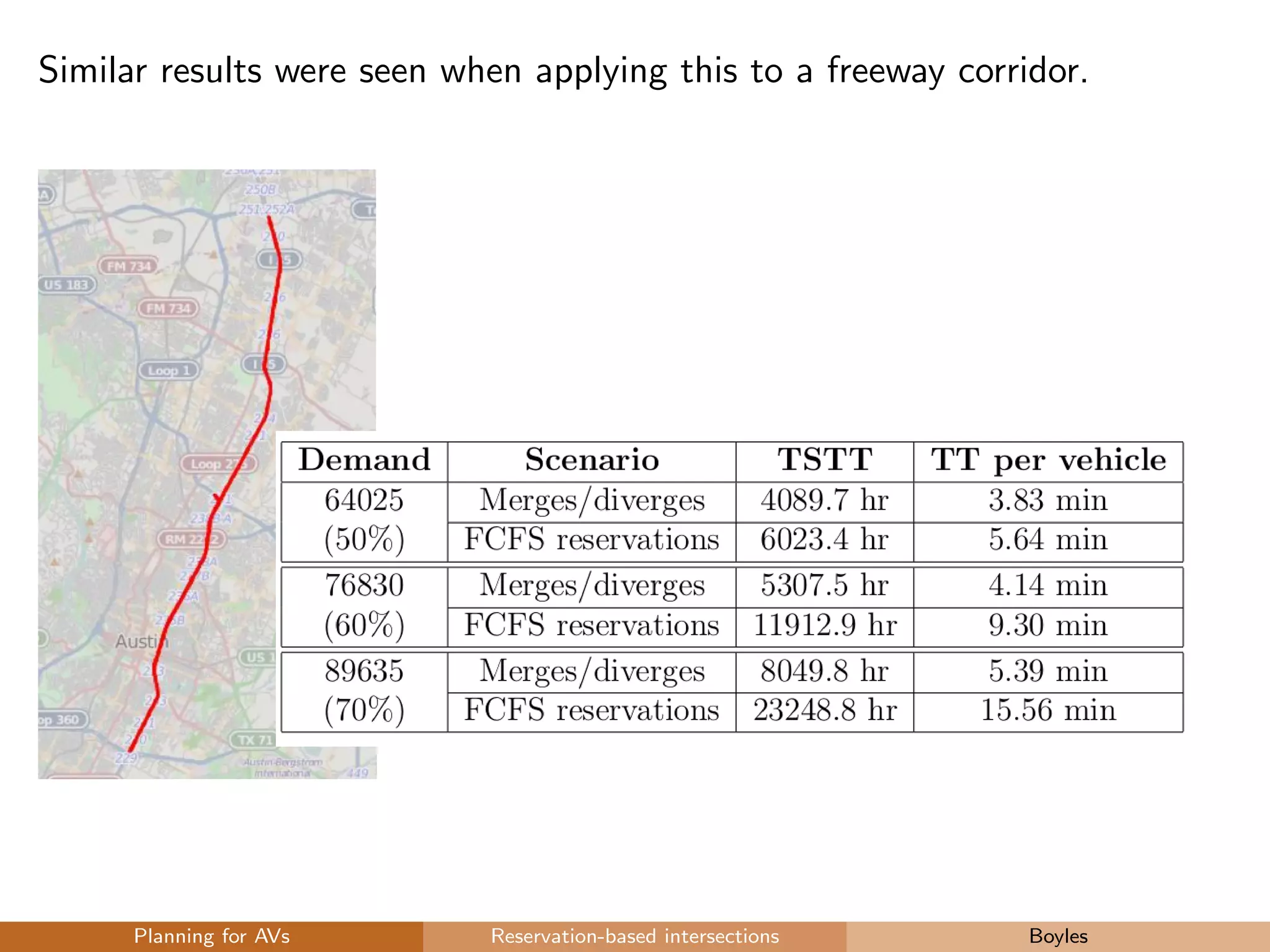

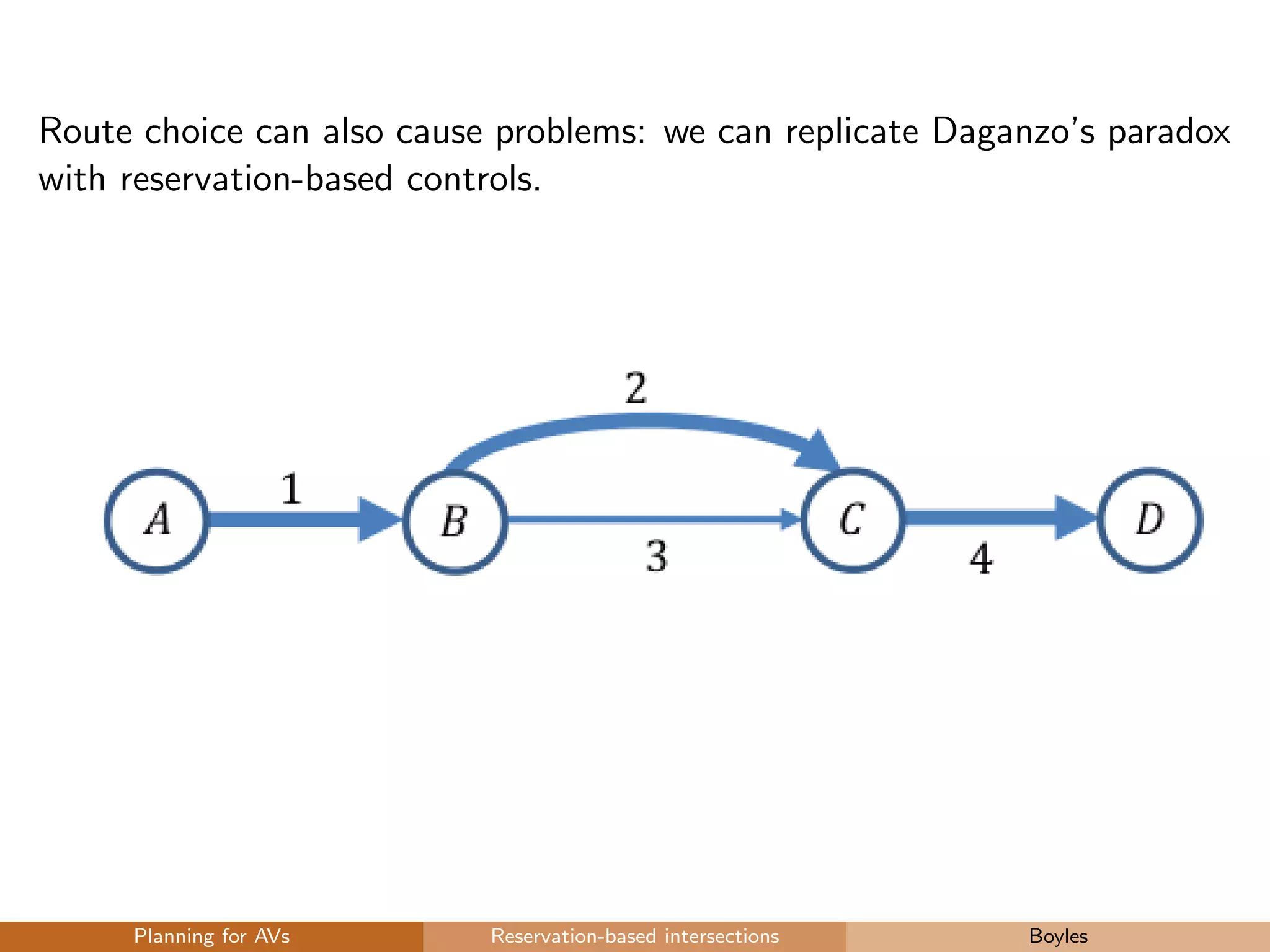

- Reservation-based intersections show potential to dramatically reduce delays, but their impacts depend on factors like route choice and asymmetric demand.

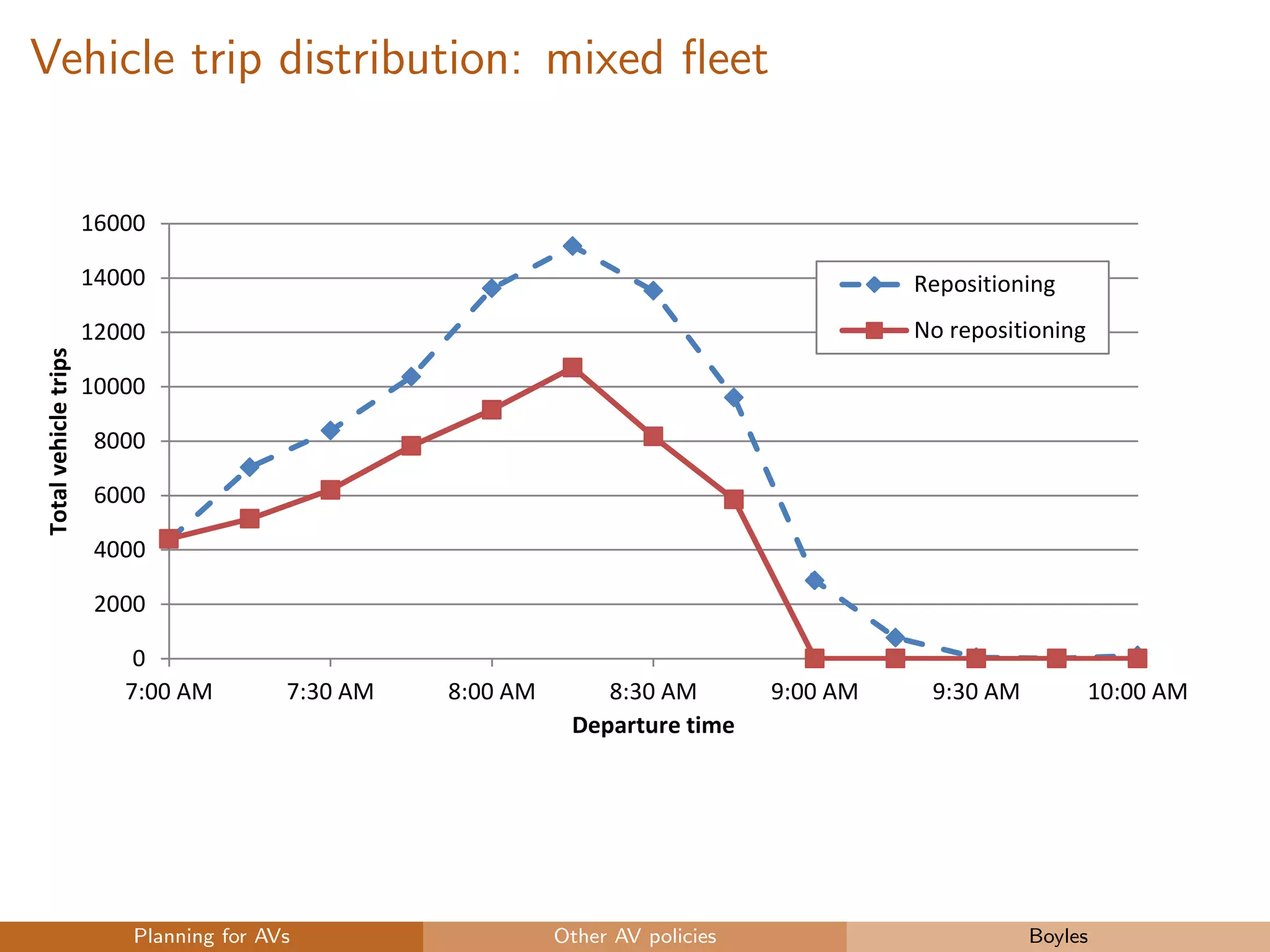

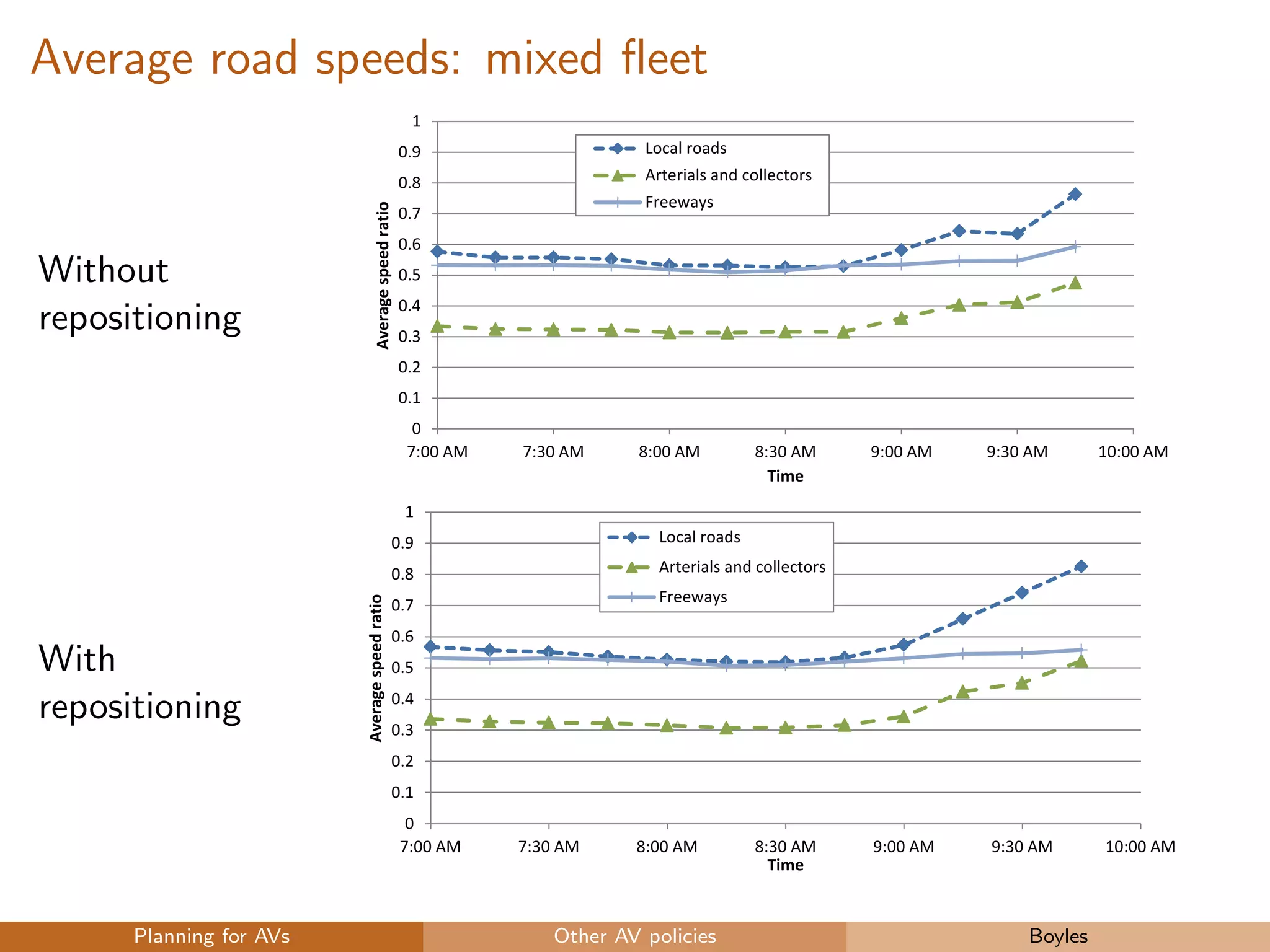

- Allowing empty automated vehicles to reposition could smooth traffic flows compared to not repositioning empty vehicles.