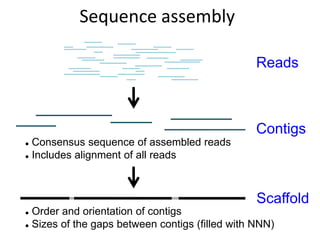

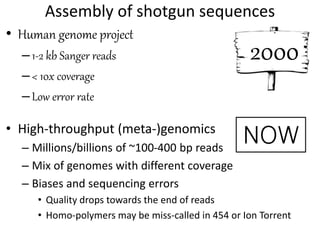

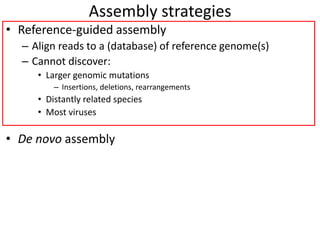

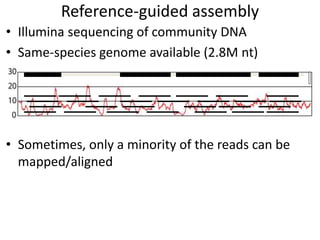

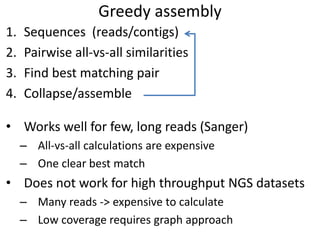

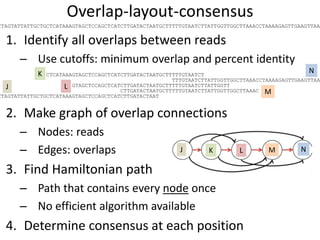

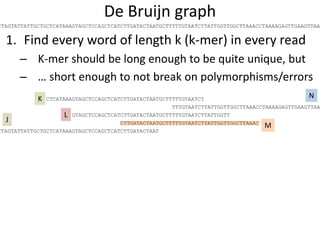

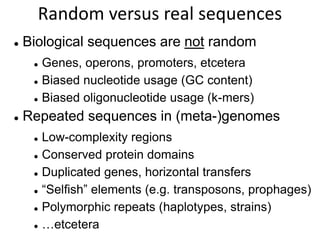

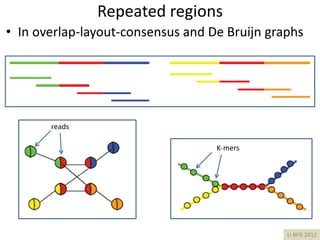

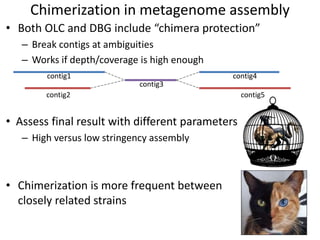

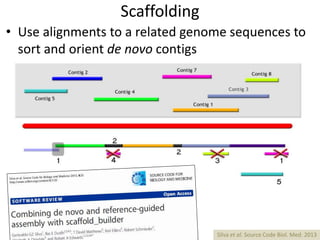

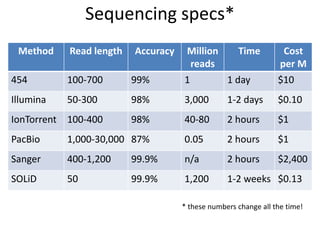

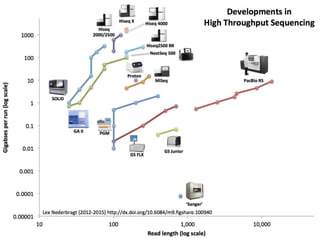

The document discusses the basic and molecular aspects of bacteriophages and their biotechnological applications, particularly in genome sequencing technologies. It compares various sequencing methods, their read lengths, accuracy, and associated costs, emphasizing the challenges of de novo and reference-guided assembly in genomics. Additionally, it explores assembly strategies and the complexities of working with biological sequences, including the presence of repeated regions and sequencing errors.

![• Simplest sequence file format

• Unique identifiers!

• “Fasta wide” format has the whole sequence on one line

• Even easier to parse in a computer script

Fasta

>identifier1 [optional information]

CCGATCATATGACTAGCATGCATCGATCGATCGACTAGCATTT

AGAGCTACGATCAGCACTACACGCTTTGTATGATTGGCGGCGG

CTATTATATTGGGA

>identifier2 [optional information]

GAGAGCTACGATCAGAGCTACGATCAGCACTACACGCTTTGTA

TGATTGGCCCCCTATATTGGGACACGATCAGCACTACACGCTT

TGTATGATTGGCGGCGGCTATCCGATCAT](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/20150629-cabbioassembly-160408091803/85/Metagenome-Sequence-Assembly-CABBIO-20150629-Buenos-Aires-7-320.jpg)