1. Create an Excel spreadsheet with the following columns Title, .docx

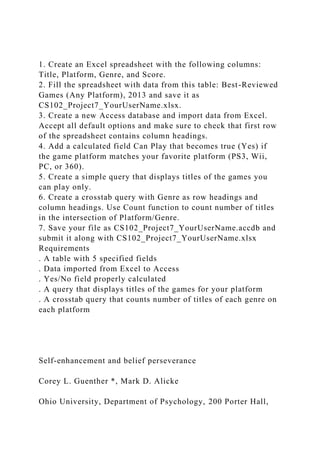

- 1. 1. Create an Excel spreadsheet with the following columns: Title, Platform, Genre, and Score. 2. Fill the spreadsheet with data from this table: Best-Reviewed Games (Any Platform), 2013 and save it as CS102_Project7_YourUserName.xlsx. 3. Create a new Access database and import data from Excel. Accept all default options and make sure to check that first row of the spreadsheet contains column headings. 4. Add a calculated field Can Play that becomes true (Yes) if the game platform matches your favorite platform (PS3, Wii, PC, or 360). 5. Create a simple query that displays titles of the games you can play only. 6. Create a crosstab query with Genre as row headings and column headings. Use Count function to count number of titles in the intersection of Platform/Genre. 7. Save your file as CS102_Project7_YourUserName.accdb and submit it along with CS102_Project7_YourUserName.xlsx Requirements . A table with 5 specified fields . Data imported from Excel to Access . Yes/No field properly calculated . A query that displays titles of the games for your platform . A crosstab query that counts number of titles of each genre on each platform Self-enhancement and belief perseverance Corey L. Guenther *, Mark D. Alicke Ohio University, Department of Psychology, 200 Porter Hall,

- 2. Athens, OH 45701, USA Received 23 June 2006; revised 17 April 2007 Available online 30 April 2007 Abstract Belief perseverance—the tendency to make use of invalidated information—is one of social psychology’s most reliable phenomena. Virtually all of the explanations proffered for the effect, as well as the conditions that delimit it, involve the way people think about or explain the discredited feedback. But it seems reasonable to assume that the importance of the feedback for the actor’s self- image would also influence the tendency to persevere on invalidated feedback. From a self-enhancement perspective, one might ask: Why would peo- ple persist in negative self-beliefs, especially when the basis for those beliefs has been discredited? In the present study, actors and observ- ers completed a word-identification task and were given bogus success or failure feedback. After success feedback was discredited, actors and observers persevered equally in beliefs about the actor’s abilities. However, following invalidation of failure feedback, actors pro- vided significantly higher performance evaluations than observers, thus exhibiting less perseverance on the negative feedback. These results suggest that the motivation to maintain a relatively favorable self-image may attenuate perseverance when discredited feedback threatens an important aspect of the self-concept. ! 2007 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

- 3. Keywords: Self-enhancement; Belief perseverance; Motivation; Self-perception; Self-evaluation; Task-importance; Failure feedback People believe many things that turn out to be untrue but are not always able or willing to revise their beliefs. Superstitions abound, and they require only sporadic rein- forcement to be held tenaciously (Skinner, 1948). Further- more, numerous studies show that believing occurs more automatically than revising (Gilbert, 1991), which helps to explain why many beliefs outlive the data that discredit them. The steadfastness of beliefs in the face of invalidating evidence is a topic that traverses many research areas in psychology including correspondence bias (Gilbert & Mal- one, 1995; Jones & Harris, 1967), psycho-legal studies of inadmissible evidence (e.g., Johnson & Seifert, 1994; Kas- sin & Sommers, 1997; Sue, Smith, & Caldwell, 1973; Thompson, Fong, & Rosenhan, 1981), and basic research on impression formation (Schul & Burnstein, 1985; Schul & Goren, 1997; Wyer & Unverzagt, 1985). But the research area that addresses this tendency most directly is called ‘‘belief perseverance’’. Ross, Lepper, and Hubbard (1975), following up an earlier study by Walster, Berscheid, Abrahams, and Aronson (1967), conducted the experi- ments that stimulated widespread interest in this phenom- enon. Participants in their studies evaluated the genuineness of suicide notes in what they believed was a study on physiological responses during decision making. After being connected to electrodes and making their judg- ments, participants received bogus feedback which indi- cated that they had succeeded or failed at the task. Participants were subsequently told that the feedback was

- 4. fictitious and that the purpose of the study was to assess physiological responses to success and failure feedback. They then estimated their actual performance. Despite hav- ing been told that the feedback was fabricated, participants who received success feedback continued to evaluate them- selves more favorably than those who received failure feed- back. Parallel effects were obtained from observers who witnessed the feedback being administered and saw it discredited. 0022-1031/$ - see front matter ! 2007 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2007.04.010 * Corresponding author. Fax: +1 740 593 0579. E-mail address: [email protected] (C.L. Guenther). www.elsevier.com/locate/jesp Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 44 (2008) 706–712 mailto:[email protected] Ross et al. argued that perseverance occurs because peo- ple spontaneously construct causal stories to explain the original feedback. These explanations become highly acces- sible and autonomous from the information on which they were based, and contain new inferences that are relatively impervious to invalidation. According to this view, some- one who succeeds or fails imagines various causal factors that could have produced this outcome, and when the ori- ginal feedback is discredited, these new causal inferences inadvertently affect the person’s attributions. This assump-

- 5. tion is consistent with the general conclusion that consider- ing alternative hypotheses corrects numerous social judgment biases (e.g., Koriat, Lichtenstein, & Fischhoff, 1980; Lord, Lepper, & Preston, 1984). Numerous experi- ments have supported these assumptions (e.g., Anderson, 1982, 1983; Anderson, Lepper, & Ross, 1980; Anderson, New, & Speer, 1985; McFarland, Cheam, & Buehler, 2007), although there is some question as to whether the generation of causal explanations is always required for belief perseverance (Wegner, Coulton, & Wenzlaff, 1985). Although competing explanations continue to be prof- fered for belief perseverance (see also, Anderson & Lind- say, 1998; Anderson & Sechler, 1986; Lieberman & Arndt, 2000; Nisbett & Ross, 1980; Smith, 1982), there is little doubt that the tendency to adhere to initial feedback is one of the most reliable effects in the social judgment canon. In fact, belief perseverance is so powerful that to date, researchers have reported relatively few factors that moderate its strength. Among the moderating factors iden- tified is explicitly informing participants about the pro- cesses underlying perseverance (Ross et al., 1975), increasing self-awareness (Davies, 1982), having partici- pants generate alternatives to the feedback (Anderson, 1982; Anderson & Sechler, 1986; Massad, Hubbard, & Newtson, 1979), and telling participants that both the feed- back and the test from which it was generated are bogus (McFarland et al., 2007). So far, the factors that have been shown to moderate belief perseverance have all involved the way participants attend to, think about, or explain the feedback they receive. But there is another class of moderating factors that could plausibly affect the tendency to be influenced by discredited feedback, namely, the importance of the feedback for peo- ple’s self-concepts. Abundant research suggests that people

- 6. generally strive to maintain the most favorable self-image that reality constraints will allow (Alicke & Govorun, 2005; Sedikides & Gregg, 2003). From this vantage, the tendency to persevere on discredited feedback (particularly unfavorable feedback) is puzzling. If people are concerned with maintaining reasonably favorable self-views, why don’t they seize the opportunity to restore positive self- evaluations when they are given every reason to believe that the unfavorable feedback was false? The main reason, we suspect, lies in the sheer strength of the perseverance effect, which constrains the operation of self-enhancement. Still, it seems reasonable to assume, based on the voluminous self-enhancement literature, that there would be circumstances in which the desire to eschew negative information about oneself would moderate belief perseverance. However, belief perseverance studies have not typically been designed to evoke self-enhancement con- cerns. For one thing, many of these studies assess judg- ments of other people rather than oneself (e.g., Anderson, 1982; Anderson et al., 1980). In studies that do include self-related judgments (e.g., Ross et al., 1975; Wegner et al., 1985), investigators do not usually portray the task as an important one for diagnosing personal char- acteristics, and thus the chances of activating self-enhance- ment motives is minimized. In the study described below, we compare actors’ and observers’ perseverance tendencies following feedback on a task that they are explicitly told involves an important characteristic, namely, intelligence. Until now, the only belief perseverance studies that employed actor–observer paradigms were the original ones by Ross et al. (1975) and those reported by Wegner et al. (1985). Neither of these studies revealed perseverance dif- ferences between actors and observers. However, these

- 7. researchers were primarily interested in establishing the perseverance effect and testing competing explanations, and did not emphasize the importance of the performance outcomes for any particular abilities or traits. In fact, par- ticipants in their studies were led to believe that the exper- imenters were interested in physiological responses during performance and that the performance outcome informa- tion itself was relatively unimportant. Our goal in the pres- ent study was to show that when the performance dimension is explicitly described as one that measures intel- ligence—an attribute that is presumably important to most college students—actors will exhibit a reduced tendency relative to observers to persevere on negative feedback. The present study Participants were told that they would complete a test of mental acuity that measured a fundamental aspect of intel- ligence. Actors actually took the test, which involved their ability to detect subliminal stimuli, and received feedback indicating that they had performed very well or very poorly. Observers saw the actor take the test and also learned of the favorable or unfavorable outcome. Experi- menters then told actors that they had applied the wrong answer key to their performance, which resulted in the actor receiving incorrect feedback. Performance ratings were obtained at three separate times: before participants began the task, after the initial feedback was received, and after the feedback was discredited. Initial ratings were used as a covariate for post-discredit ratings. Consistent with prior research, we expected to obtain perseverance effects from both actors and observers such that a significant difference between favorable and unfavor- able feedback conditions would remain in their perfor- mance judgments even after the feedback was discredited.

- 8. We further expected, however, that the magnitude of perse- verance effects would differ between actors and observers. C.L. Guenther, M.D. Alicke / Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 44 (2008) 706–712 707 Because self-enhancement is generally stronger on negative than on positive response dimensions (Alicke, Klotz, Bre- itenbecher, Yurak, & Vredenburg, 1995), we were more confident of obtaining differential perseverance following negative than positive feedback. Evidence of self-enhance- ment would be revealed by actors evaluating themselves more favorably than observers following the receipt and subsequent invalidation of negative feedback. Method Participants Participants were 122 (47 male, 75 female) undergradu- ate students whose participation partially fulfilled a requirement for introductory psychology. Procedure Participants completed the experiment individually. Upon arrival, they were seated in front of a computer and asked to complete the consent form which contained the basic instructions. The study was described as one that investigated mental acuity, defined as one of three primary components of intelligence. After the consent form was completed, further instruc- tions were delivered by computer and recited orally by

- 9. the experimenter. The instructions explained that mental acuity involved the ability to quickly identify, discriminate, and categorize information in one’s perceptual field. Partic- ipants were told that previous research has shown that those who score high on tests of mental acuity also tend to score high on tests of overall intelligence. Participants were randomly assigned to the actor and observer roles. Observers were told that through computer networking, they would observe the task as another partic- ipant completed it from another room. They were told that once the actor completed the task, they would see the actor’s score and be asked to complete a questionnaire regarding his or her performance. The task comprised a series of 25 words that would be flashed individually on the computer screen for 11 ms. After each word was shown, participants were asked to record the word they believed had been flashed on the screen. They were told that at the end of the 25 trials, a composite score would be calculated and presented, and that a short questionnaire would follow. Participants were then instructed to begin the task. Words used in the experimental task ranged in length from 4-6 letters, appeared in 22 point Times New Roman font, and were flashed on the screen for 11 ms. Each word was preceded by a masking row of 8 asterisks for 135 ms to focus participants’ attention on the center of the screen. The same 135 ms mask was added following each word. Participants were given five practice trials to familiarize themselves with the procedure before beginning the actual experimental task. Actors were given as much time as nec- essary to provide a response. On each trial, observers saw ‘‘Participant Response’’ on their screens for 3 s between

- 10. trials. The experiment was conducted using MediaLab (Jarvis, 2004a,b) and Direct RT software. Feedback manipulation After the 25 trials were completed, participants were randomly assigned to receive either positive or negative performance feedback. In the positive feedback condition, actors and observers learned that the actor had correctly identified the word on 20 of the 25 trials, which placed them at the 93rd percentile. In the negative feedback con- dition, actors and observers learned that the actor had cor- rectly identified the word on 12 of the 25 trials, which put them at the 36th percentile. Discrediting of feedback After participants had completed the task, the experi- menter returned and informed them that there had been an unfortunate mistake. The experimenter explained that there were different versions of the task, each with its own answer key, and that by accident he (she) had paired the participant’s task with the wrong answer key. Conse- quently, their test had been scored incorrectly, and the feedback they had been given did not reflect their actual performance or intelligence. Furthermore, because responses were anonymous, participants were told that there was no way to recover their test and determine their actual score. Response measures Pre-task ratings were obtained after the experimental instructions had been given but prior to the start of the task. Participants were asked to estimate, based on the description of mental acuity and the experimental task,

- 11. how many items they believed that they (or if they were in the observer role, the actor) would answer correctly, how mentally acute they thought they were (the actor was), and also at what percentile of the general population (0–100) they believed their (the actor’s) mental acuity lied. Performance estimations could range from 0–25 and men- tal acuity ratings were made on 1–10 scales (0 = extremely low, 10 = extremely high). These same judgments were made a second time after the initial feedback was adminis- tered. Here, participants were asked to make ratings based on the feedback they received. Finally, ratings were obtained a third time after the initial feedback had been discredited. Results and discussion Nine participants were excluded from the analysis because they failed to complete the primary response mea- sures. Means and standard deviations for estimates of how 708 C.L. Guenther, M.D. Alicke / Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 44 (2008) 706–712 many items the actor answered correctly, the actor’s mental acuity, and the actor’s percentile standing, are displayed in Table 1 for each of the three time frames. A preliminary 2 (actor vs. observer) · 2 (positive vs. neg- ative feedback) · 3 (pre-feedback vs. post-feedback vs. post-discredit) analysis of variance (ANOVA), with the first two variables being between subjects factors and the third measured within subjects, revealed a significant three-way interaction for ratings of actor mental acuity, F(2, 108) = 8.71, p < .0001, g2 = .139, and percentile rank,

- 12. F(2, 108) = 5.14, p < .007, g2 = .087, but was non-signifi- cant for estimates of number correct (p > .05). Because this analysis yields numerous effects, many of which are irrelevant to our primary hypotheses, we have organized the analysis below around the primary questions we sought to address. The main questions in this study were (1) whether traditional perseverance effects occurred, and (2) whether actors persevered more on positive feed- back, and less on negative feedback, than observers. Before addressing these questions, it was necessary to show that actors’ and observers’ perceptions of the actors’ abilities did not differ prior to the receipt of the feedback, and also to show that the feedback was effective in altering actors’ and observers’ initial perceptions. Were there initial actor–observer differences? Subsequent analyses would be difficult to interpret if actors and observers differed in their initial estimates of actors’ abilities. If there were initial differences, then the tendency for actors to persevere more than observers on positive feedback or less on negative feedback might simply reflect actors’ more favorable performance expectations rather than a desire to maintain a relatively favorable self-view. Because previous belief perseverance studies have not been concerned primarily with self-related judgments, pre-feedback ratings have been less crucial and not included in this research. A 2 (actor vs. observer) · 2 (positive vs. negative feed- back) ANOVA was conducted on pre-feedback ratings to determine whether actors and observers differed in their perceptions of actors’ mental acuity or abilities prior to the experimental task. This analysis yielded no actor–

- 13. observer differences on estimates of how many items the actor would answer correctly (F < 1), on initial ratings of the actor’s mental acuity (F < 1), or on estimates of the actor’s percentile standing (F < 1). Clearly, therefore, actors and observers did not differ in their perceptions of the actor’s ability prior to the administration of perfor- mance feedback. Thus, subsequent findings cannot be explained in terms of differences in initial performance expectations. Were actors and observers influenced by the feedback? Before analyzing the main factors of interest, it was also necessary to show that the positive and negative feedback had their intended effects. We expected participants in the positive feedback condition to increase their evaluations of the actor following feedback administration, and those in the negative feedback condition to decrease their evalu- ations. To this end, a 2 (actor vs. observer) · 2 (positive vs. negative feedback) · 2 (pre-feedback vs. post-feedback) analysis was conducted with the first two factors measured between subjects and the third measured within subjects. Changes in actor evaluations in the positive and negative feedback conditions are indicated by the interaction between the repeated factor (before feedback evaluations, after feedback evaluations) and positive vs. negative feed- back. This interaction was significant on estimates of how many items the actor answered correctly, F(1, 109) = 65.62, p < .0001, g2 = .376, ratings of the actor’s mental acuity, F(1, 109) = 124.81, p < .0001, g2 = .534, and estimates of the actor’s percentile standing, F(1, 109) = 247.92, p < .0001, g2 = .695. No other interac- tions were significant. As Table 1 shows, both actors and observers in the positive feedback condition increased their evaluations when the initial feedback was received, while

- 14. Table 1 Means and standard deviations for actor-ratings: before feedback, after feedback, and after feedback is discredited Measure Positive Negative Actors Observers Actors Observers Estimated number correct Before feedback M 17.00 17.89 17.50 17.39 SD 3.10 7.69 4.54 3.92 After discredit M 19.16 19.68 15.00 13.04 SD 2.93 1.42 3.20 2.34 Ratings of mental acuity Before feedback M 6.39 6.07 6.50 6.04 SD 1.33 0.98 1.39 0.90 After feedback M 7.55 8.46 4.69 4.21 SD 1.34 0.96 2.26 1.29 After discredit M 7.10 7.86 6.15 5.00 SD 1.27 1.14 1.67 0.78 Percentile estimate Before feedback

- 15. M 68.67 69.32 73.04 65.32 SD 12.83 13.46 12.41 12.12 After feedback M 89.32 87.75 31.42 33.11 SD 11.78 17.50 15.10 15.25 After discredit M 82.42 87.07 55.75 42.96 SD 12.85 8.54 20.85 16.26 Note. Estimations for number correct could range from 0 to 25. Ratings of mental acuity were made on an 11-point scale ranging from 0 to 10. Estimations of percentile rank could range from 0 to 100. C.L. Guenther, M.D. Alicke / Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 44 (2008) 706–712 709 those in the negative feedback condition decreased their evaluations when the initial feedback was received. Thus, the bogus feedback did have the intended effects of raising evaluations of the actor’s ability in the positive feedback condition and lowering them in the negative feedback condition. Did perseverance occur? Our first primary research question was whether tradi- tional perseverance was observed. Perseverance is usually defined in terms of differences in evaluations between posi- tive and negative feedback conditions even after research participants are told that the feedback was bogus or erro-

- 16. neous. Following this traditional methodology, a 2 (actor vs. observer) · 2 (positive vs. negative feedback) ANOVA was conducted to compare post-discredit ratings made by participants in the positive and negative feedback condi- tions. Consistent with previous research, we expected par- ticipants in the positive feedback condition to provide significantly more favorable actor evaluations than those in the negative feedback condition. Results supported this prediction. A main effect of feedback was obtained whereby participants given positive, discredited feedback estimated that the actor got more items correct, F(1, 109) = 125.14, p < .0001, g2 = .534, provided higher ratings of actors’ mental acuity, F(1, 109) = 63.81, p < .0001, g2 = .369, and estimated actors’ mental acuity to lie at a higher percentile, F(1, 109) = 154.05, p < .0001, g2 = .586, than did participants who had been given nega- tive, discredited feedback, thus replicating the usual belief perseverance findings. Actor–observer perseverance differences in positive and negative feedback conditions The final and most important question we addressed was whether actors persevered more on positive discredited feedback than observers, and less on negative discredited feedback, after controlling for initial evaluations. The fact that there were no differences in initial evaluations, of course, suggests that covarying these evaluations should have little effect on the results. As previously discussed, because self-enhancement is generally stronger on negative than on positive response dimensions (Alicke et al., 1995), we were more confident of obtaining differential perseverance between actors and observers in the negative feedback condition. Results of a 2 (actor vs. observer) · 2 (positive vs. negative feedback)

- 17. analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) on post-discredit evalu- ations, controlling for initial ratings, confirmed this assumption. Significant interactions, each revealing a simi- lar pattern, were obtained for estimates of how many items the actor answered correctly, F(1, 108) = 6.30, p < .014, g2 = .055, ratings of the actor’s mental acuity, F(1, 108) = 21.24, p < .001, g2 = .164, and estimates of the actor’s percentile standing, F(1, 108) = 7.02, p < .009, g2 = .061. Following the receipt of positive, discredited feedback, actors and observers provided virtually identical estimates of the number of items the actor answered cor- rectly and the percentile rank of his or her performance (Fs < 1). There were actor–observer differences in ratings of mental acuity, F(1, 108) = 11.99, p < .001, g2 = .100, but it was the observer ratings that were more positive than actor ratings. Thus, there was no evidence of self-enhance- ment in positive feedback conditions. By contrast, significant differences between actors and observers for attributions regarding negative discredited feedback were obtained on each measure. After controlling for initial evaluations, actors who received negative feed- back that was later discredited estimated that they had answered more items correctly, F(1, 108) = 7.92, p < .006, g2 = .068, that they possessed more mental acuity, F(1, 108) = 9.14, p < .003, g2 = .078, and also estimated that their performance fell at a higher percentile, F(1, 108) = 6.39, p < .013, g2 = .056, than did observers. Thus, differential perseverance was obtained in the negative feedback condition, as actors tended to inflate their self- evaluations and perseverate to a lesser extent than did observers. The present study, therefore, is the first of which we are aware to demonstrate actor–observer differences in attribu-

- 18. tions following discredited feedback. These differences were obtained, however, primarily following negative feedback. Specifically, actors showed less perseverance on negative feedback that was discredited than did observers. From the standpoint of self-enhancement, one might question why actors didn’t also show an increased tendency to per- severe on positive feedback relative to observers. One pos- sibility is a simple ceiling effect. After positive feedback was discredited, the perseverance effect led both actors and observers to give the actor high ratings, leaving little room on the respective scales for actors to elevate their ratings above those of observers. Another explanation is that self-enhancement tendencies tend to be stronger on nega- tive response dimensions than on positive ones (Alicke & Govorun, 2005; Chambers & Windshitl, 2004; Sedikides & Gregg, 2003). After the discrediting manipulation, actors and observers in the positive feedback condition gave actors relatively high ratings on mental acuity, estimated that the actor was correct on about 20 of 25 trials, and also estimated the actor’s percentile rank to lie near the 85th percentile, so there was relatively little need for actors to exhibit further self-enhancement. The experimental design of the present study also allowed us to eliminate a possible alternative explanation for the observed actor–observer differences. In virtually all published belief perseverance studies, participants’ responses are obtained only after the initial feedback is dis- credited. The finding that actors evaluate themselves more favorably than observers after unfavorable feedback is dis- credited could simply reflect initial attributional differences. According to this interpretation, participants essentially ignore the feedback after it is discredited and revert to their 710 C.L. Guenther, M.D. Alicke / Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 44 (2008) 706–712

- 19. initial expectations, which are higher than those of observ- ers. The present study, however, refutes this interpretation. No actor–observer differences were obtained before the feedback was administered, and therefore, controlling for initial evaluations did not influence the results. The absence of initial differences is consistent with the general finding that self-enhancement is minimized when actors expect to be evaluated on highly objective tasks (Alicke & Govorun, 2005). Thus, the results of the study reported in this paper sug- gest that people do show decreased perseverance when the experimental task is described as one that measures an important self-component, which in the present studies, was represented as mental acuity—a purportedly vital aspect of intelligence. We believe that the data make a com- pelling argument that when the task is an important one, the desire to maintain a relatively favorable self-image leads actors to perseverate less than observers on unfavor- able feedback. This is a potentially important self-evalua- tion maintenance mechanism. Everyone receives negative feedback, and while it would be unwise simply to ignore objective evaluations, it is equally unwise to subscribe to negative feedback whose validity is questionable. Of the numerous mechanisms that people use to help maintain positive self-views, knowing how to handle negative feed- back effectively may be among the most important. People learn about themselves from various sources—by testing their skills vs. the environment or other people, by receiving scores on objective tests, and via verbal feedback provided in relatively formal (e.g., performance evalua- tions) or informal (e.g., comments by an acquaintance)

- 20. circumstances. A difficult, but indispensable, aspect of self-evaluation requires people to assess the validity of these data sources. Some feedback is almost impossible to challenge, such as reading a stop watch to calculate one’s running time, whereas other feedback, such as a perfor- mance evaluation from a non-expert source, may be eschewed as worthless. In the belief perseverance paradigm, information that initially appears to be highly credible is subsequently called into question. It is important to note that although exper- imenters tell participants that the feedback was erroneous, the feedback may still provide the baseline from which they estimate their true performance. Thus, participants may believe that they are discarding the feedback without real- izing that they are using it as a judgmental anchor. In our view, the main cause of belief perseverance is not that peo- ple fail to appreciate the invalidity of the initial feedback, or that they make new inferences in seeking to make sense of it, but rather, that they inadvertently use this feedback as an anchor from which to rate their abilities at the task. The present findings add to the research literature that examines the interplay between cognitive and motivational factors in social judgment and behavior (Kunda, 1990). While there may be some aspects of judgment and behavior that are purely habitual or automatic, most interesting social phenomena contain chronic or situational goals that the actor is trying to achieve, as well as cognitive processes by which those goals are pursued. In belief perseverance, actors’ have to assess their ability at the task, and the way they do this is heavily influenced by the initial, invali- dated feedback that they received. The present research is the first to show that this process is alterable when the task is described as an important one for the self-concept and

- 21. actors, therefore, have the goal of maintaining a reasonable favorable self-view on the performance dimension. References Alicke, M. D., & Govorun, O. (2005). The better-than-average effect. In M. D. Alicke, D. A. Dunning, & J. I. Krueger (Eds.), The self in social judgment (pp. 85–106). NY: Psychology Press. Alicke, M. D., Klotz, M. L., Breitenbecher, D. L., Yurak, T. J., & Vredenburg, D. S. (1995). Personal contact, individuation, and the better-than-average effect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychol- ogy, 68, 804–825. Anderson, C. A. (1982). Inoculation and counterexplanation: Debiasing techniques in the perseverance of social theories. Social Cognition, 1, 126–139. Anderson, C. A. (1983). Abstract and concrete data in the perseverance of social theories: When weak data lead to unshakable beliefs. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 19, 93–108. Anderson, C. A., Lepper, M. R., & Ross, L. (1980). Perseverance of social theories: The role of explanation in the persistence of discredited information. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39,

- 22. 1037–1049. Anderson, C. A., & Lindsay, J. J. (1998). The development, perseverance, and change of naı̈ ve theories. Social Cognition, 16, 8–30. Anderson, C. A., & Sechler, E. S. (1986). Effects of explanation and counterexplanation on the development and use of social theories. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50, 24–34. Anderson, C. A., New, B. L., & Speer, J. R. (1985). Argument availability as a mediator of social theory perseverance. Social Cognition, 3, 235–249. Chambers, J. R., & Windshitl, P. D. (2004). Biases in social comparative judgments: The role of nonmotivated factors in above-average and comparative-optimism effects. Psychological Bulletin, 130, 813–838. Davies, M. F. (1982). Self-focused attention and belief perseverance. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 18, 595–605. Gilbert, D. T. (1991). How mental systems believe. American Psychologist, 46, 107–119. Gilbert, D. T., & Malone, P. S. (1995). The correspondence bias. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 21–38.

- 23. Jarvis, B. (2004a). Direct RT (v2004) [Computer Software]. New York: Empirisoft Corporation. Jarvis, B. (2004b). MediaLab (v2004) [Computer Software]. New York: Empirisoft Corporation. Jones, E. E., & Harris, V. A. (1967). The attribution of attitudes. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 3, 2–24. Johnson, H. M., & Seifert, C. M. (1994). Sources of the continued influence effect: When misinformation in memory affects later infer- ences. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning Memory, and Cognition, 20, 1420–1436. Kassin, S. M., & Sommers, S. R. (1997). Inadmissible testimony, instructions to disregard, and the jury: Substantive versus procedural considerations. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23, 1046–1054. Koriat, A., Lichtenstein, S., & Fischhoff, B. (1980). Reasons for confidence. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Learning and Memory, 6, 107–118. Kunda, Z. (1990). The case for motivated reasoning. Psychological Bulletin, 108, 480–498.

- 24. C.L. Guenther, M.D. Alicke / Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 44 (2008) 706–712 711 Lieberman, J. D., & Arndt, J. (2000). Understanding the limits of limiting instructions: Social psychological explanations for the failures of instructions to disregard pretrial publicity and other inadmissible evidence. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 6, 677–711. Lord, C. G., Lepper, M. R., & Preston, E. (1984). Considering the opposite: A corrective strategy for social judgment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47, 1231–1243. Massad, C. M., Hubbard, M., & Newtson, D. (1979). Selective perception of events. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 15, 513– 532. McFarland, C., Cheam, A., & Buehler, R. (2007). The perseverance effect in the debriefing paradigm: Replication and extension. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 43, 233–240. Nisbett, R., & Ross, L. (1980). Human inference: Strategies and shortcomings of judgment. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Ross, L., Lepper, M. R., & Hubbard, M. (1975). Perseverance in self- perceptions and social perception: Biased attributional

- 25. processing in the debriefing paradigm. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 32, 880–892. Schul, Y., & Burnstein, E. (1985). When discounting fails: Conditions under which individuals use discredited information in making a judgment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 49, 894–903. Schul, Y., & Goren, H. (1997). When strong evidence has less impact than weak evidence: Bias, adjustment, and instructions to ignore. Social Cognition, 15, 133–155. Sedikides, C., & Gregg, A. P. (2003). Portraits of the self. In M. A. Hogg & J. Cooper (Eds.), Sage handbook of social psychology (pp. 110–138). London: Sage Publications. Skinner, B. F. (1948). Superstition in the pigeon. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 38, 168–172. Smith, M. J. (1982). Cognitive schema theory and the perseverance and attenuation of unwarranted empirical beliefs. Communication Mono- graphs, 49, 115–126. Sue, S., Smith, R. E., & Caldwell, C. (1973). Effects of inadmissible evidence on the decisions of simulated jurors: A moral dilemma.

- 26. Proceedings of the Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association, 263–264. Thompson, W. C., Fong, G. T., & Rosenhan, D. L. (1981). Inadmissible evidence and juror verdicts. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 40, 453–463. Walster, E., Berscheid, E., Abrahams, D., & Aronson, V. (1967). Effectiveness of debriefing following deception experiments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 6, 371–380. Wegner, D. M., Coulton, G. F., & Wenzlaff, R. (1985). The transparency of denial: Briefing in the debriefing paradigm. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 49, 338–346. Wyer, R. S., & Unverzagt, W. H. (1985). Effects of instructions to disregard information on its subsequent recall and use in making judgments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48, 533–549. 712 C.L. Guenther, M.D. Alicke / Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 44 (2008) 706–712 Self-enhancement and belief perseveranceThe present studyMethodParticipantsProcedureFeedback manipulationDiscrediting of feedbackResponse measuresResults and discussionWere there initial actor-observer differences?Were actors and observers influenced by the feedback?Did perseverance occur?Actor-observer perseverance

- 27. differences in positive and negative feedback conditionsReferences Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 43 (2007) 233–240 www.elsevier.com/locate/jesp 0022-1031/$ - see front matter © 2006 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2006.01.010 The perseverance eVect in the debrieWng paradigm: Replication and extension ! Cathy McFarland a,¤, Adeline Cheam a, Roger Buehler b a Department of Psychology, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, BC, Canada V5A 1S6 b Wilfrid Laurier University, Waterloo, Ont., Canada N2L 3C5 Received 9 November 2005; revised 11 November 2005 Available online 29 March 2006 Abstract A classic study conducted by Ross, Lepper, and Hubbard (1975) revealed a perseverance eVect wherein people who received positive performance feedback on an alleged social perceptiveness test reported more favorable self-perceptions in this domain than those who received negative feedback despite the fact that they had received standard outcome debrieWng (i.e., been informed about the false, prede- termined, and random nature of the feedback) prior to reporting

- 28. self-assessments. The present studies extend this past research by reveal- ing that (a) there is a form of outcome debrieWng (i.e., informing participants about the bogus nature of the test as well as the bogus nature of the feedback) that eVectively eliminates the perseverance eVect, (b) the perseverance eVect that occurs after standard outcome debrieWng is limited to perceptions of speciWc task-relevant skills rather than more global abilities, and (c) aVective reactions do not underlie the perseverance eVect that occurs in the false feedback paradigm. © 2006 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Keywords: The perseverance eVect; DebrieWng; Self- perception; False feedback In a study investigating how threats to self-esteem aVect social perceptions, Charlotte received feedback indicating that she performed at the 30th percentile on a test that pur- portedly measured intellectual ability. Shortly thereafter, she evaluated a target person, and was then thoroughly debriefed. The experimenter explained why it was necessary to present a cover story, stressed that her score was randomly determined in advance, and highlighted that her score reXected nothing about her true intellectual ability. Nonethe- less, as she headed home, Charlotte found herself wondering about her ability to succeed in university, and seriously con- templated whether she really has what it takes to be a lawyer. This perseverance eVect, wherein people cling to newly formed beliefs even when the evidential basis for those beliefs is completed refuted, was demonstrated convincingly in a classic study conducted by Ross et al. (1975). Their research revealed that participants who were provided with false feed-

- 29. back indicating that they performed well on a test of social perceptiveness ability provided more favorable self-evalua- tions after debrieWng than did participants who were told that they performed poorly. In other words, the self-perceptions of task-relevant skills that were elicited by the feedback “per- severed” despite extensive debrieWng. Presumably, such beliefs persist because subjects attempt to generate explana- tions for the initial outcome (e.g., I am a pretty outgoing per- son and that is why I did so well), and the causal factors they identify continue to predict the outcome even when the out- come that prompted the explanation is invalidated (Ander- son, Lepper, & Ross, 1980; Ross, Lepper, Strack, & Steinmetz, 1977). Although conducted over a quarter century ago, Ross et al.’s research continues to have important ethical implications for researchers in social psychology. The false ! This research was supported by SSHRC standard research grants awarded to the Wrst and third authors. We thank Celeste Alvaro, Paul Conway, Vivian Hsing, and Diane Lines for their assistance with the research. * Corresponding author. E-mail address: [email protected] (C. McFarland). 234 C. McFarland et al. / Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 43 (2007) 233–240 feedback paradigm has been used to study many social psy- chological phenomena, including reactions to social compar-

- 30. isons (e.g., Crocker, Thompson, McGraw, & Ingerman, 1987; McFarland & Buehler, 1995; Tesser, Millar, & Moore, 1988); the impact of threats to self-esteem on self-evaluation (e.g., Brown & Smart, 1991; Dunning, Leuenberger, & Sherman, 1995), social comparison judgments (e.g., Brown & Galla- gher, 1992), aggression (Stucke & Sporer, 2002), and preju- dice (e.g., Fein & Spencer, 1997); the role of individual diVerences in emotional, cognitive, and behavioral reactions to performance feedback (e.g., Baumeister, Heatherton, & Tice, 1993; Blaine & Crocker, 1993; Di Paula & Campbell, 2002; McFarlin, 1985; Wood, Giordano-Beech, Taylor, Michela, & Gaus, 1994, 1999); the relation between mood and cognition (e.g., Forgas, 2000; Schwarz & Clore, 1996); and the nature of emotions and emotional regulation in the aftermath of distressing events (Brown & Dutton, 1995; Brown & Marshall, 2001; Dodgson & Wood, 1998; Forgas & Ciarrochi, 2002; McFarland & Buehler, 1998; Nummenmaa & Niemi, 2004). Given the continued and widespread use of the false feedback paradigm, it is essential that researchers have at their disposal debrieWng techniques that can eVec- tively eliminate the perseverance phenomenon. The goal of our research was to critically examine the debrieWng process and further clarify the precise features that make for an eVec- tive debrieWng in this paradigm. The current research We conducted two studies that were designed to extend Ross et al.’s (1975) Wndings regarding the nature of an eVec- tive debrieWng. Before presenting our precise goals, it is important to consider their research in greater detail. In their main study, participants were Wrst informed that the research was examining “physiological responses during decision making.” Next, while attached to a recording device, they completed a decision-making task (i.e., distinguishing real from fake suicide notes) that purportedly assessed social per-

- 31. ceptiveness ability.1 After receiving either success or failure feedback, they were assigned to one of three groups. In the outcome debrieWng condition, participants were informed of the “true” purpose of the study (“to examine physiological reactions to feedback”), and that their feedback was false, randomly assigned, predetermined, and non-reXective of their actual ability. In the process debrieWng condition, partic- ipants received the same information as that provided to out- come debrieWng participants, with one important addition: they were informed about the perseverance phenomenon and encouraged to avoid engaging in this cognitive process. In the no debrieWng condition, participants did not receive a debrieWng at this point in the session. Participants then com- pleted three assessments of belief perseverance: (1) estimates of current performance and predictions regarding future per- formance on an equally diYcult set of notes, (2) evaluations of ability on the speciWc task (i.e., identifying real suicide notes), and (3) ratings of abilities presumably related to social perceptiveness (i.e., recognizing falsehood, sensitivity to others’ feelings, and test-taking skills). A perseverance eVect would be revealed if post-debrieWng self-perceptions in the success group were more favorable than those in the fail- ure group. The results indicated that although process debrieWng was eVective in eliminating perseverance on all measures, outcome debrieWng yielded a perseverance eVect on both performance estimates and ratings of ability on the speciWc task.2 Our research had four objectives. First, we assessed the possibility that there is a form of outcome debrieWng that can be eVective in eliminating perseverance. One notewor- thy feature of the original Ross et al. (1975) research is that although debriefed participants were told that their score on the test was bogus, they were led to believe that the test itself was a valid test of an important underlying ability,

- 32. and that therefore, a “real” score on the test actually existed. It seems possible that this feature of the debrieWng might make the perseverance eVect more likely. Presum- ably, participants who have received outcome debrieWng might Wnd themselves wondering what their real score on the test is, and might even use the fake score as an anchor with which to estimate their real score (Cervone & Palmer, 1990; Mussweiler, Strack, & PfeiVer, 2000; Wegner, Coul- ton, & WenzlaV, 1985).3 In essence, curiosity about one’s real score could engender a train of thought that leads par- ticipants to construct a scenario or image of their actual performance that is consistent with their randomly assigned performance. This, image, in turn, might engender further self-relevant thoughts (e.g., attributions to stable qualities, self-praise or criticism) that ultimately create per- severance in self-perceptions. In our research, we developed a revised form of outcome debrieWng that included infor- mation indicating that the test itself was not a real validated test of social perceptiveness ability. We expected that the addition of this feature would eliminate the perseverance eVect that is normally obtained with outcome debrieWng. Second, we explored the generality of the perseverance eVect that occurs after standard outcome debrieWng. In Ross et al. (1975), perseverance was strongest on self-perceptions that were speciWc to the test-domain (i.e., performance esti- mates and ratings of the ability to identify real suicide notes). However, although they assessed perceptions of a few “related 1 Dr. Lepper (personal communication, August, 1997) has conWrmed that participants were told that the decision-making task assessed general social perceptiveness ability. The original (1975) report did not mention this point explicitly.

- 33. 2 We focused our discussion on Study 2 of the Ross et al. (1975) report because it included a “no debrieWng” control group and a process de- brieWng group. The results of their Study 1, which included only the out- come debrieWng condition, were comparable to those of Study 2, except that perseverance was obtained on the “related abilities” measure. 3 Some anecdotal support for this assumption can be found in the spon- taneous comments made by participants from other studies in our lab. We regularly use false feedback, and have found that it is not uncommon for participants to ask for information about their “real” score after being de- briefed. Indeed, it is these comments that sparked the current research. C. McFarland et al. / Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 43 (2007) 233–240 235 skills,” they did not ask participants to rate themselves on the precise global dimension allegedly assessed by the suicide note task—social perceptiveness ability. In our research, we included several items to assess participants’ perceptions of their global social perceptiveness skills. Based on Ross et al.’s Wndings, we expected that perseverance would likely be lim- ited to speciWc ratings. However, it seemed worthwhile to assess the generality of the perseverance eVect because their

- 34. preliminary study (see Footnote 2) did reveal an eVect on the “related skills” measure. Moreover, given that the test is por- trayed as assessing a general ability, it seems plausible that perseverance could occur on more global perceptions. The generality of the perseverance eVect is an important issue. If the phenomenon extends to perceptions of global abilities then the prescription that researchers conduct debrieWngs that completely eliminate perseverance is rendered ever more pressing. Finally, we examined the possibility that the persever- ance eVect occurring after standard outcome debrieWng might be due to “aVective perseverance” (e.g., Sherman & Kim, 2002). Ross et al. discussed, but were not able to test, the possibility that perseverance in self-perceptions could derive from mood reactions that are not completely elimi- nated through debrieWng. Presumably, participants’ post- debrieWng moods could inXuence self-perceptions via mood-congruent processing (e.g., Brown & Mankowski, 1993; Sedikides & Green, 2001). We included a post- debrieWng mood assessment to evaluate this notion. Study 1 Using a procedure closely modeled after that used by Ross et al. (1975), participants were exposed to either suc- cess or failure feedback on an alleged test of social percep- tiveness that involved distinguishing real from fake suicide notes. They then received one of four debrieWng inductions: (1) standard outcome debrieWng (i.e., participants were told about the “true” purposes, and that their score was false, predetermined, and randomly assigned), (2) revised out- come debrieWng (i.e., participants received standard out- come debrieWng and learned that the test was bogus), (3) process debrieWng (i.e., participants received standard out- come debrieWng and information regarding perseverance),

- 35. or (4) no debrieWng. After the debrieWng variation, partici- pants provided current and future performance estimates, ratings of their speciWc and global abilities, and mood rat- ings. We predicted that perseverance would occur in only the standard outcome debrieWng condition, and that it would be limited to ratings of performance and speciWc task-relevant skills. We also evaluated whether aVective reactions mediated the perseverance eVect. Method Participants and design The participants were 67 female and 61 male SFU undergraduates who took part individually and were pro- vided with course credit for participating. They were ran- domly assigned to the conditions of a 2 (feedback: success vs. failure) £ 4 (debrieWng condition: no debrieWng vs. stan- dard outcome debrieWng vs. revised outcome debrieWng vs. process debrieWng) between-subjects factorial design. Males and females were distributed approximately equally across the conditions. Preliminary analyses indicated that there were no interactions involving gender; thus, the primary analyses do not include gender as a factor. Procedure Participants were Wrst provided with a cover story indi- cating that the researchers were exploring “personality traits and physiological responses during decision-making.” Accordingly, they Wrst completed a personality survey, after which they were attached to physiological recording equip- ment. During a “baseline assessment of arousal,” they read an information sheet indicating that the decision-making task involved reading 15 pairs of suicide notes, and select-

- 36. ing the one “real” note from each pair. The task was described as a widely used measure of social perceptiveness- “the ability to make accurate judgments about other peo- ple’s behaviors and motives.” This ability was depicted as an important attribute that is linked to a wide variety of positive outcomes. Participants then completed the test, after which they were told to sit still while a “post-task reading” was obtained. At this time, the experimenter left the room brieXy to “score the test.” Feedback manipulation The experimenter returned and presented the participant with a feedback sheet tucked inside the test booklet. The feedback sheets were prepared in advance, ensuring that the experimenter remained blind to condition. Participants were told that their score was either 14/15 (success) or 4/15 (failure), and that the average was 9/15. DebrieWng manipulation After a few minutes, the experimenter removed the elec- trodes, and delivered one of the debrieWng variable induc- tions. Participants in the no debrieWng condition were told that while their credit form was being prepared they were to complete a Wnal “thoughts and reactions” questionnaire (see below). In the debrieWng conditions, the experimenter explained that the study was actually examining “the eVects of feedback on physiological responses,” and that it had therefore been necessary to provide false test feedback. Par- ticipants in the standard outcome debrieWng condition were informed that their score was a fake score that had been randomly assigned to them prior to their arrival. Addition- ally, they were shown a “random assignment schedule,” and the experimenter emphasized that the score contained absolutely no information about the participant’s actual

- 37. performance or underlying abilities. Participants in the revised outcome debrieWng condition were provided with the same information as that provided to those in the standard outcome debrieWng group. 236 C. McFarland et al. / Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 43 (2007) 233–240 Importantly, however, they were also told that the suicide- note test was a fake test that had been made to look like a real test. The experimenter explained that all of the suicide notes in the test were fake notes, and that the test did not measure any underlying abilities. Participants in the process debrieWng condition were also provided with the same information as that provided to stan- dard outcome debrieWng participants. Additionally, however, they were informed about the nature of the perseverance eVect and how it might have personal relevance for them in this context. The experimenter highlighted that people’s beliefs sometimes persist even after debrieWng because they generate independent evidence that explains the feedback, and urged participants to avoid thinking in this way. Dependent measures Next, the experimenter asked participants to complete a “thoughts and reactions” questionnaire. They were assured of anonymity and asked to place the completed question- naire into a sealed unmarked envelope and place it amongst other unmarked envelopes. The Wrst section consisted of Wller questions (e.g., clarity of instructions) that validated the cover story. Participants then completed two items

- 38. assessing their perceptions of performance on the suicide note task. One item requested that they estimate their score on the suicide note test out of 15. The wording of this ques- tion was carefully tailored to each debrieWng condition to ensure that the question made sense in light of the details of each condition. Participants in the no-debrieWng condition were asked to recall the score they had just been assigned. Participants in the standard outcome debrieWng and process debrieWng conditions (who were told that their score was fake) were asked to estimate their “actual score on the sui- cide note test (/15).” Participants in the revised outcome debrieWng condition, who were told that the test was not real, were asked the following: “Even though you now know that the task was not actually a real test of your abil- ity to distinguish genuine from Wctitious suicide notes, imagine for a moment right now that it had been a real test (i.e., one including real and fake notes). If you took this test now, what would you estimate to be your score on the test?.” Participants also estimated their future performance on a diVerent, but equally diYcult, set of genuine and fake notes. As well, they evaluated the speciWc ability to distin- guish real from fake suicide notes (1 D much lower ability than average; 11 D much higher ability than average). Next, participants responded to 8 scales (range 1–11) assessing their perceptions of their global abilities: good at detecting another’s distress (extremely poor-extremely good); good at understanding why people behave in certain ways (extremely poor-extremely good); likelihood of pursuing a job requiring social perceptiveness skill (extremely unlikely-extremely likely); good at being a psychologist (extremely poor-extremely good); socially percep- tive (extremely low-extremely high); sensitive to others’ feel- ings (extremely insensitive-extremely sensitive); good at taking tests under pressure (extremely poor-extremely

- 39. good); ability to recognize falsehood (extremely poor- extremely good). The latter three items constitute Ross et al.’s (1975) “related skills” measure. Finally, participants rated their current moods (happy, satisWed, pleased, disappointed, sad, proud, and competent; 1Dnot at all; 9Dextremely). Final debrieWng Participants in all conditions received a Wnal “process” debrieWng. The experimenter explained the exact hypothe- ses, the necessity for the elaborate deception, and the fake nature of the test. Results and discussion Creation of indexes We Wrst constructed several indexes: (1) performance estimate index (i.e., the average of current and future score estimates, ! D .81), (2) global abilities index (i.e., the average of the 8 global ratings, ! D .80), and (3) mood (i.e., the aver- age of the 7 mood ratings with the 2 negative items reverse scored, ! D .85). Performance estimates We predicted that a perseverance eVect on performance estimates would occur in only the standard outcome debrieWng condition. Revised outcome and process debrieWng were expected to eliminate perseverance. A 2 (feedback)£ 4 (debrieWng) ANOVA performed on this index revealed two main eVects (debrieWng: F (3, 120)D8.90, p < .0001; feedback: F (1, 120)D48.90, p < .0001) that were qualiWed by a signiWcant interaction eVect (F (3, 120)D57.76, p < .0001) that supported the prediction (see Table 1). Not surprisingly, among those

- 40. who were not debriefed, participants who received success feedback reported higher estimates (M D13.18) than those who received failure feedback (M D4.46), t (120) D15.03, p < .001. Importantly, though, even among those who received standard outcome debrieWng, recipients of success feedback reported higher estimates (MD9.33) than recipients of failure feedback (MD7.96), t (120) D2.49, p < .05 (i.e., a perseverance eVect). The success–failure diVerence was not signiWcant (ts < 1) in the revised and process debrieWng groups, indicating that perseverance was eliminated in these conditions.4 4 On the performance estimate measure, the variability in the control groups was lower than that found in the debrieWng groups, probably be- cause control participants found it relatively easy to recall the score they received a short while before. Consequently, the overall error term may be somewhat lower than it would be if these control groups were not included in the analysis. To assess whether the perseverance eVect obtained in the standard outcome debrieWng group would remain signiWcant if an alterna- tive error term was used, we conducted an independent-groups t test that used the two pertinent cell variances to represent error variability. The per- severance eVect was maintained, t (30) D 2.40, p < .05. As well, we assessed whether the signiWcant interaction eVect would be preserved if a more stringent critical F value were used. We conducted the conservative Box test for heterogeneous variances outlined in Howell (2002), and

- 41. the inter- action eVect remained signiWcant, p < .05. In sum, the Wndings on the per- formance estimate measure are not attributable to the lower variances in the control conditions. C. McFarland et al. / Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 43 (2007) 233–240 237 SpeciWc ability rating Again, a perseverance eVect was anticipated in only the standard outcome debrieWng condition. A 2 £ 4 ANOVA performed on the speciWc ability rating revealed two main eVects (debrieWng: F (3, 120) D 4.72, p < .01; feedback: F (1, 120) D 39.62, p < .0001) that were qualiWed by a signiW- cant interaction eVect (F (3, 120) D 50.59, p < .0001) that supported the prediction (see Table 1). As expected, non- debriefed participants who received success feedback reported a greater ability to distinguish real from fake sui- cide notes (M D 9.36) than those who received failure feed- back (M D 3.07), t (120) D 13.97, p < .001. Consistent with predictions, recipients of standard outcome debrieWng revealed a marginally signiWcant perseverance eVect (suc- cess: M D 7.20; failure M D 6.47), t (120) D 1.78, p < .08. Per- severance did not occur in the revised or process debrieWng groups (success vs. failure ts < 1, ns). Global ability ratings One goal of our research was to examine whether perse- verance occurs on the more global dimension purportedly assessed by the suicide note task. A 2 £ 4 ANOVA per-

- 42. formed on the global ability index revealed that the perse- verance eVect was not obtained on evaluations of general social perceptiveness skills. Although a signiWcant interac- tion was obtained (F (3, 120) D 2.63, p < .05), it occurred solely because non-debriefed “success” participants reported greater global ability (M D 7.84) than non- debriefed “failure” participants (M D 6.82), t (120) D 2.62, p < .01. No evidence for perseverance was obtained within any debrieWng condition (i.e., all ps > .20). Separate analyses of the individual items that were included in the overall global index revealed a similar pattern of eVects—no evi- dence of perseverance in any debrieWng group (again, all relevant ps > .20). Thus, it appears that when the persever- ance eVect occurs, it is limited to perceptions of speciWc task-relevant features (i.e., score estimates, and ratings of task speciWc ability). It is worth noting as well that although failure feedback decreased global ability ratings (relative to the combined failure debrieWng condition means) it does not appear that positive feedback increased global ratings. The debrieWng condition averages can be interpreted as representing a “baseline” global ability rating, and the mean in the no debrieWng/success group did not diVer from the mean of the combined success (or failure) debrieWng groups. It seems, then, that participants had rather Table 1 Dependent variables as a function of type of performance feedback and debrieWng technique Note. Higher scores on the performance estimate index reXect higher performance (/15). Higher scores on the ability measures indicate greater ability (1– 11). Within rows and columns for each measure, means not sharing a common subscript letter diVer at the .05 level (two- tailed). There is one exception: on

- 43. the speciWc ability rating, the success vs. failure diVerence is marginally signiWcant within the standard debrieWng condition (p < .08). Measure and type of feedback Type of debrieWng No debrieWng Standard outcome debrieWng Revised outcome debrieWng Process debrieWng Performance estimates Failure M 4.46a 7.96b 10.38c 8.85b N 14 17 17 17 SD .49 1.40 1.81 2.11 Success M 13.18d 9.33c 10.08 c 8.03b N 14 15 17 17 SD .99 1.79 1.66 1.50 SpeciWc ability rating Failure M 3.07a 6.47c 7.53d 7.12c, d N 14 17 17 17 SD .83 1.17 1.55 1.49 Success M 9.36 b 7.20d 7.24 d 6.65d N 14 15 17 17 SD 1.08 1.08 1.30 .93 Global ability ratings Failure

- 44. M 6.82a 7.69c 7.48c, a 7.47c, a N 14 17 17 17 SD 1.45 1.07 1.23 1.15 Success M 7.84c 7.45c 7.86c 7.01c N 14 15 17 17 SD 1.10 1.09 1.08 .85 238 C. McFarland et al. / Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 43 (2007) 233–240 favorable preexisting views of their global social perceptive- ness abilities, and that positive feedback did not further ele- vate these self-views. Mood ratings To test whether post-debrieWng mood reactions engender perseverance in self-perceptions through mood-congruent processing, we Wrst conducted a 2 £ 4 ANOVA on the mood index. This analysis revealed a marginally signiWcant interac- tion eVect (F (3, 120) D 2.41, p < .07) wherein the diVerence between the success and failure conditions was signiWcant only among non-debriefed participants (success M D 6.77; failure M D 5.47; t (120)D 3.25, p < .001). If aVective reactions underlie the perseverance eVect obtained in the standard out- come debrieWng condition, participants in this group who received success feedback should have reported more posi- tive moods (M D 6.33) than those who received failure feed- back (M D 6.42), and they did not, t < 1, ns. As an additional test, we reran the ANOVAs conducted on the performance estimate and speciWc ability measures (i.e., the measures that revealed perseverance) using mood as a covariate. Both inter-

- 45. action eVects were maintained when mood was controlled (estimates (F (3, 119) D 53.23, p < .0001); speciWc ability rating (F (3, 119)D 46.83, p < .0001)). Thus, the perseverance eVect occurring on these measures does not appear to be due to aVective perseverance. Study 2 Study 1 revealed that a slightly revised form of out- come debrieWng can be as eVective as process debrieWng in eliminating perseverance. When participants were informed not only that their score was false, but also that the test was not a valid measurement tool, their post- debrieWng self-perceptions were uninXuenced by false feedback. In Study 2, we explored the possibility that revised outcome debrieWng may be more eVective than standard outcome debrieWng because it preempts a pat- tern of thought that occurs in the latter form of debrieWng. When participants receive standard outcome debrieWng, they probably Wnd themselves contemplating or ruminat- ing about their “real score” on what they have been led to believe is a valid test. This curiosity about their real score may lead them to use their assigned score as a subjective anchor point with which to estimate their real score (Weg- ner et al., 1985), and the constructed score representation could lead to further thoughts that reXect explanations of the hypothetical score (Fleming & Arrowood, 1979; Ross et al., 1975). These types of thoughts would be expected to yield perseverance in self-perceptions. In contrast, in revised outcome debrieWng, participants learn that the test is bogus, and thus they should be much less likely to rumi- nate about what their real score might be. Study 2 explored this reasoning. Recipients of failure feedback received one of three forms of debrieWng: standard out- come, revised outcome, or process debrieWng. Immedi-

- 46. ately after debrieWng, we obtained several measures reXecting the degree of contemplation regarding actual performance levels. We expected that recipients of revised outcome debrieWng would ruminate less about their real performance than participants in the other conditions. Method Participants Participants were 6 male and 24 female SFU undergrad- uates who received course credit. Procedure The procedure closely paralleled that used in the fail- ureEdebrieWng conditions of Study 1 up to the point at which the initial debrieWngs were completed. At this point, the experimenter left the room for 4 min, and returned with the “thoughts and reactions questionnaire.” After a couple of Wller questions, participants were informed that we were interested in the thoughts that people have after learning about our true purposes, and that they should indicate the degree to which they had certain thoughts during the past few minutes. On a scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 11 (a great deal), they indicated the degree to which they found themselves (a) wondering about or contemplating what their real score on a test of social perceptiveness might be, (b) wondering about what their actual ability level is in the domain of social perceptiveness, and (c) thinking that the score they were given on the test might be a useful starting point for estimating their actual performance/ability on a test of social perceptiveness. They were then fully debriefed.5

- 47. Results We predicted that participants in the revised outcome debrieWng condition would think less about their real score or ability level than participants in the other debrieWng con- ditions. A one-way ANOVA performed on an index reXect- ing the average of the three contemplation items (! D .76) revealed support for this prediction, F (2, 27) D 5.56, p < .01. Immediately after debrieWng, recipients of revised outcome debrieWng reported thinking about their score and ability level signiWcantly less (M D 5.16) than did recipients of stan- dard outcome debrieWng (M D 7.56; t (27) D 2.75, p < .01) or process debrieWng (M D 7.76; t (27) D 2.98, p < .01). 5 We did not include the perseverance measures because we reasoned that they would be tainted by the previous act of completing the contem- plation measures, and thus would not yield the typical perseverance eVect (i.e., lower ratings in the standard outcome debrieWng condition than the other conditions). We reasoned that even participants who reported think- ing little about their real score during the previous few minutes (i.e., those in the revised outcome debrieWng group) would be prompted to think about it after completing items that inquired explicitly about this score. Thus, the contemplation measures are reactive in the sense that completing them would likely create perseverance in most participants.

- 48. C. McFarland et al. / Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 43 (2007) 233–240 239 General discussion Prior to the publication of Ross et al.’s research in 1975, it seems likely that most social psychologists simply assumed that their debrieWngs were eVective. After all, why would research participants who are told that they lack an important intellectual or social skill not embrace informa- tion conveying that the feedback is invalid? By demonstrat- ing the perseverance eVect, and revealing a strategy to eliminate this phenomenon, Ross and colleagues provided the Weld with both a “wake-up call” and a solution. In the past quarter century, process debrieWng has become the most widely accepted protocol for the proper conduct of debrieWngs (e.g., Aronson, Ellsworth, Carlsmith, & Gonza- les, 1990) and authors often mention explicitly that this is the form of debrieWng that they delivered. The current studies build upon this classic early work in several ways. First, our Wndings revealed that there is a form of outcome debrieWng that is as eVective as process debrieWng in eliminating perseverance. It appears that the addition of one piece of information (i.e., information that the test is invalid or bogus), is suYcient to prevent perse- verance in performance-related self-perceptions. Based on our Wndings, one might be tempted to suggest that researchers use revised outcome debrieWng in lieu of pro- cess debrieWng. This position is not without merit. Revised outcome debrieWng appears to work because it preempts the ruminative processing that normally serves to solidify feedback-based self-perceptions. Successful process debrieWng, in contrast, probably requires that participants engage in a more eVortful or controlled corrective process (e.g., Wegener & Petty, 1997) wherein they adjust rumina-

- 49. tion-inspired self-perceptions in a direction that opposes the feedback. Study 2 oVered some indirect support for this possibility: Participants in the process debrieWng con- dition were as likely as those in the standard outcome debrieWng condition to report ruminating about their per- formance; nonetheless, they managed to avoid persever- ance (see Study 1). If this general reasoning is correct, it could be argued that revised outcome debrieWng will be more eVective than process debrieWng among participants who are less motivated or able to engage in an eVortful correction process. Despite this advantage, however, we believe that a “combined” debrieWng would be most eYcacious [i.e., one that incorporates the best features of both revised outcome (i.e., information about test invalid- ity) and process debrieWng (i.e., information about perse- verance)]. This form of debrieWng would not only preempt perseverance among participants who are less inclined to engage in correction, but also provide a long-term strat- egy for all participants to use in the event that they experi- ence feedback-consistent self-thoughts after leaving the laboratory. Combined debrieWng does require that researchers use test items that do not actually represent valid measures of underlying ability (e.g., that they use word completions rather than GRE test items as measures of “intellectual aptitude”); however, this should not gen- erally pose a problem because studies incorporating the false feedback paradigm rarely call for the use of vali- dated tests of underlying abilities. Participants need only believe that a test measures important abilities for this paradigm to be eVective. Our research also extends Ross et al.’s research by conWrming that the perseverance eVect is restricted to people’s perceptions of speciWc performances and abili- ties. This lack of perseverance on evaluations of global

- 50. ability cannot be easily attributed to methodological fac- tors. The global ability index included multiple items, was internally consistent, and was sensitive to negative feedback. Moreover, the cover story delivered to partici- pants stressed that the test measured important general abilities. We can only speculate, but the absence of perse- verance on this index may reXect the operation of self- enhancement or self-veriWcation motives. Much past research has revealed that the average person processes information in a manner that conWrms a generally posi- tive stable self-view (e.g., Swann, Pelham, & Krull, 1989; Taylor & Brown, 1988). The results on the global ability index are consistent with this general Wnding. “Failing” participants appear to have been quite willing to relin- quish negative global perceptions that were formed tem- porarily in reaction to the feedback. Additionally, “succeeding” participants appear to have been unwilling to modify (in response to either feedback or debrieWng) the highly positive self-views that they “brought with them” to the experiment. Overall, the Wndings on the global ability index can be taken as “good news” for researchers who use false feedback. In an attempt to cap- ture the strong motivational forces and threatening emo- tions that aVect people in everyday life, researchers often portray their tests as measuring highly important and global abilities. Our results imply that when researchers use this strategy, their participants are unlikely to suVer long-term negative consequences. Finally, our results revealed that the perseverance eVect obtained in the debrieWng paradigm is not due to “aVective perseverance.” Participants’ aVective reactions revealed no evidence of perseverance, and perseverance in self-perceptions occurred even when mood reactions were controlled. Thus, debrieWng of any kind appears to be eVective in eliminating the mood changes produced by

- 51. false feedback. Although some researchers have obtained evidence for aVective perseverance in other paradigms (Sherman & Kim, 2002), perseverance in the debrieWng paradigm appears to be due to more cognitive (e.g., rumi- native) processes. In conclusion, our research highlights that there are sev- eral critical features of an eVective debrieWng in the false feedback paradigm. In particular, the distinction between “debrieWng about the false nature of the feedback” and “debrieWng about the false or unvalidated nature of the test itself” appears to be an important one, and we hope that future researchers will construct debrieWngs that reXect both of these components. 240 C. McFarland et al. / Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 43 (2007) 233–240 References Anderson, C. A., Lepper, M. R., & Ross, L. (1980). Perseverance of social theories: The role of explanation in the persistence of discredited infor- mation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39, 1037–1049. Aronson, E., Ellsworth, P. C., Carlsmith, J., & Gonzales, M. H. (1990). Methods of research in social psychology. New York: McGraw- Hill. Baumeister, R. F., Heatherton, T. F., & Tice, D. M. (1993). When ego

- 52. threats lead to self-regulation failure: Negative consequences of high self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64, 141–156. Blaine, B., & Crocker, J. (1993). Self-esteem and self-serving biases in reac- tions to positive and negative events. In R. Baumeister (Ed.), Self- esteem: The puzzle of low self-regard (pp. 55–85). New York: Plenum. Brown, J. D., & Gallagher, F. M. (1992). Coming to terms with failure: Pri- vate self-enhancement and public self-eVacement. Journal of Experi- mental Social Psychology, 28, 3–22. Brown, J. D., & Dutton, K. A. (1995). The thrill of victory, the complexity of defeat: Self-esteem and people’s emotional reactions to success and failure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68, 712– 722. Brown, J. D., & Marshall, M. A. (2001). Self-esteem and emotion: Some thoughts on feelings. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27, 575–584. Brown, J. D., & Smart, S. A. (1991). The self and social conduct: Linking self-representations to prosocial behaviour. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60, 368–375.