Colonial and Post-Colonial Religious Tests as a Basis for the First Amendment

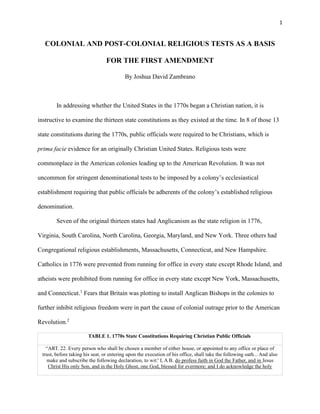

- 1. 1 COLONIAL AND POST-COLONIAL RELIGIOUS TESTS AS A BASIS FOR THE FIRST AMENDMENT By Joshua David Zambrano In addressing whether the United States in the 1770s began a Christian nation, it is instructive to examine the thirteen state constitutions as they existed at the time. In 8 of those 13 state constitutions during the 1770s, public officials were required to be Christians, which is prima facie evidence for an originally Christian United States. Religious tests were commonplace in the American colonies leading up to the American Revolution. It was not uncommon for stringent denominational tests to be imposed by a colony’s ecclesiastical establishment requiring that public officials be adherents of the colony’s established religious denomination. Seven of the original thirteen states had Anglicanism as the state religion in 1776, Virginia, South Carolina, North Carolina, Georgia, Maryland, and New York. Three others had Congregational religious establishments, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New Hampshire. Catholics in 1776 were prevented from running for office in every state except Rhode Island, and atheists were prohibited from running for office in every state except New York, Massachusetts, and Connecticut.1 Fears that Britain was plotting to install Anglican Bishops in the colonies to further inhibit religious freedom were in part the cause of colonial outrage prior to the American Revolution.2 TABLE 1. 1770s State Constitutions Requiring Christian Public Officials “ART. 22. Every person who shall be chosen a member of either house, or appointed to any office or place of trust, before taking his seat, or entering upon the execution of his office, shall take the following oath... And also make and subscribe the following declaration, to wit:' I, A B. do profess faith in God the Father, and in Jesus Christ His only Son, and in the Holy Ghost, one God, blessed for evermore; and I do acknowledge the holy

- 2. 2 scriptures of the Old and New Testament to be given by divine inspiration.' And all officers shall also take an oath of office.” -Constitution of Delaware; 17763 “ART. VI. The representatives shall be chosen out of the residents in each county, who shall have resided at least twelve months in this State, and three months in the county where they shall be elected; except the freeholders of the counties of Glynn and Camden, who are in a state of alarm, and who shall have the liberty of choosing one member each, as specified in the articles of this constitution, in any other county, until they have residents sufficient to qualify them for more; and they shall be of the Protestent religion, and of the age of twenty-one years, and shall be possessed in their own right of two hundred and fifty acres of land, or some property to the amount of two hundred and fifty pounds.” -Constitution of Georgia; February 5, 17774 “XXXV. That no other test or qualification ought to be required, on admission to any office of trust or profit, than such oath of support and fidelity to this State, and such oath of office, as shall be directed by this Convention or the Legislature of this State, and a declaration of a belief in the Christian religion.” -Constitution of Maryland - November 11, 17765 “XVIII. That no person shall ever, within this Colony, be deprived of the inestimable privilege of worshipping Almighty God in a manner, agreeable to the dictates of his own conscience; nor, under any presence whatever, be compelled to attend any place of worship, contrary to his own faith and judgment; nor shall any person, within this Colony, ever be obliged to pay tithes, taxes, or any other rates, for the purpose of building or repairing any other church or churches, place or places of worship, or for the maintenance of any minister or ministry, contrary to what he believes to be right, or has deliberately or voluntarily engaged himself to perform. XIX. That there shall be no establishment of any one religious sect in this Province, in preference to another; and that no Protestant inhabitant of this Colony shall be denied the enjoyment of any civil right, merely on account of his religious principles; but that all persons, professing a belief in the faith of any Protestant sect. who shall demean themselves peaceably under the government, as hereby established, shall be capable of being elected into any office of profit or trust, or being a member of either branch of the Legislature, and shall fully and freely enjoy every privilege and immunity, enjoyed by others their fellow subjects. XXIII. That every person, who shall be elected as aforesaid to be a member of the Legislative Council, or House of Assembly, shall, previous to his taking his seat in Council or Assembly, take the following oath or affirmation, viz:' I, A. B., do solemnly declare, that, as a member of the Legislative Council, [or Assembly, as the case may be,] of the Colony of New-Jersey, I will not assent to any law, vote or proceeding, which shall appear to me injurious to the public welfare of said Colony, nor that shall annul or repeal that part of the third section in the Charter of this Colony, which establishes, that the elections of members of the Legislative Council and Assembly shall be annual; nor that part of the twenty-second section in said Charter, respecting the trial by jury, nor that shall annul, repeal, or alter any part or parts of the eighteenth or nineteenth sections of the same.'” -Constitution of New Jersey; 17766 “XXXII.(5) That no person, who shall deny the being of God or the truth of the Protestant religion, or the divine authority either of the Old or New Testaments, or who shall hold religious principles incompatible with the freedom and safety of the State, shall be capable of holding any office or place of trust or profit in the civil department within this State.” -Constitution of North Carolina: December 18, 17767 “SECT. 10. A quorum of the house of representatives shall consist of two-thirds of the whole number of members elected... And each member, before he takes his seat, shall make and subscribe the following declaration, viz: I do believe in one God, the creator and governor of the universe, the rewarder of the good and the punisher of the wicked. And I do acknowledge the Scriptures of the Old and New Testament to be given by Divine inspiration. And no further or other religious test shall ever hereafter be required of any civil officer or magistrate in this State.” -Constitution of Pennsylvania - September 28, 17768

- 3. 3 “III. That as soon as may be after the first meeting of the senate and house of representatives, and at every first meeting of the senate and house of representatives thereafter, to be elected by virtue of this constitution, they shall jointly in the house of representatives choose by ballot from among themselves or from the people at large a governor and commander-in-chief, a lieutenant-governor, both to continue for two years, and a privy council, all of the Protestant religion, and till such choice shall be made the former president or governor and commander-in- chief, and vice-president or lieutenant-governor, as the case may be, and privy council, shall continue to act as such.” -Constitution of South Carolina - March 19, 17789 “SECTION IX. A quorum of the house of representatives shall consist of two-thirds of the whole number of members elected... And each member, before he takes his seat, shall make and subscribe the following declaration, viz. 'I ____ do believe in one God, the Creator and Governor of the Diverse, the rewarder of the good and punisher of the wicked. And I do acknowledge the scriptures of the old and new testament to be given by divine inspiration, and own and profess the protestant religion.' And no further or other religious test shall ever, hereafter, be required of any civil officer or magistrate in this State.” -Constitution of Vermont - July 8, 177710 As observed by Pyle & Davidson (2003), most of the 96 founding fathers (55.21%) were Episcopalian; founding fathers being defined as signers of the Declaration of Independence or Delegates to the 1787 Constitutional Convention. An additional 21.88% were Congregationalists, 13.54% Presbyterians, 3.13% Quakers, 3.13% Roman Catholics, 1.04% Dutch Reformed, 1.04% Methodist, and 1.04% Baptist. (p. 70) Religious Tolerance in Post-Colonial America: Madison, Jefferson, and Virginia Baptists Virginia’s religious test would play a key role in the formation of the First Amendment and initiated a rapid increase in religious tolerance during the early post-colonial period. The history of the First Amendment is invariably bound to the unique relationship held by James Madison and Thomas Jefferson to the Virginia Baptists. The Bill of Rights, including the First Amendment, was the result of ten objections raised by the leader of the Virginia Baptists, John Leland, an anti-slavery abolitionist and advocate for religious freedom. The Virginia Baptists at the time were concerned that without a guarantee of religious liberty Baptists would be

- 4. 4 discriminated against under the new U.S. Constitution by a state church like Virginia’s Anglican state church, as had been occurring for more than a century prior.i As chance would have it, the 1788 election in which James Madison was running as a Virginia Delegate was threatened. Madison, as the primary architect of the U.S. Constitution at the time, found not only his own election chances imperiled, but the fate of the entire U.S. Constitution which at the time he was championing. Fortunately, Madison had an existing friendly relationship with Leland, and by agreeing to create a Bill of Rights, Madison won election and the U.S. Constitution was passed.11 Indeed, both Jefferson and Madison had worked with Leland’s Virginia Baptists to protect their religious freedom since at least 1773, when Madison had publicly spoken out on their behalf to condemn the “diabolical, hell-conceived principle of persecution.” ii Jefferson and Madison collaborated to produce the 1779 Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom guaranteeing religious freedom to all religions, which in 1785 was followed by Madison’s legislation, A Memorial and Remonstrance Against Religious Assessments, which argued that promotion of any religion was outside the scope of government and essential to preserving the inalienable rights given by God.12 The origins of the Bill of Rights itself derived from George Mason, who in September of 1787 insisted that the Constitution include a ‘Declaration of Rights.’ Mason withheld his support for the U.S. Constitution, and refused to sign it because it did not enumerate such rights.13 Letters between Jefferson, who at the time was in France, and James Madison then ensued from 1787- i Under Virginia laws attendance at Episcopal (Anglican) churches had been mandatory, the doors of dissenting denominations had to be unlocked (to allow for easy disruption and arrest of dissenters), taxes were collected to support the Anglican Church, and dissenting ministers had to be registered within their locales, sign all articles of the Anglican Church, and provide court records of all places they intended to hold worship. ii Given Madison’s persistent efforts to create religious liberty for the Baptists even before his decision to enter politics, it appears likely that Leland was assisting Madison at Madison’s request to help him win election for the purpose of creating religious freedom for minorities such as the Baptists.

- 5. 5 89, with Jefferson himself urging Madison to include a Bill of Rights and extracting a promise from Madison to include what would become the first ten amendments to the U.S. Constitution.14 The concept of a Bill of Rights itself dates considerably earlier in the colonial period, as evidenced by the 1702 Charter of Privileges passed by William Penn’s Province of Pennsylvania, which included freedoms of religion for all Christians, democratic representation, and fair trial on the basis of God-given inalienable rights.15 The Legislation of Jefferson and Madison: Hardly Secular The legislation produced by both Thomas Jefferson and James Madison leading up to the Bill of Rights displays fully their advocacy for the Virginia Baptists, and their desire to protect religious expression. Neither article of legislation displays a hint of secular motivation. Jefferson’s legislation, the Virginia Statute, opens with a bold argument that religious restrictions go against the will of the Creator: “Whereas, Almighty God hath created the mind free; That all attempts to influence it by temporal punishments or burthens, or by civil incapacitations tend only to beget habits of hypocrisy and meanness, and therefore are a departure from the plan of the holy author of our religion, who being Lord, both of body and mind yet chose not to propagate it by coercions on either, as was in his Almighty power to do, That the impious presumption of legislators and rulers, civil as well as ecclesiastical, who, being themselves but fallible and uninspired men have assumed dominion over the faith of others, setting up their own opinions and modes of thinking as the only true and infallible, and as such endeavouring to impose them on others, hath established and maintained false religions over the greatest part of the world and through all time…” -Thomas Jefferson, Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom16 As for Madison’s own legislation, the Memorial and Remonstrance Against Religious Assessments, it similarly began with an openly religious tone, asserting that inalienable rights are given by a Creator, and therefore inviolate from the encroachments of human governance.

- 6. 6 “We remonstrate against the said Bill, 1. Because we hold it for a fundamental and undeniable truth, 'that religion or the duty which we owe to our Creator and the manner of discharging it, can be directed only by reason and conviction, not by force or violence.' The Religion then of every man must be left to the conviction and conscience of every man; and it is the right of every man to exercise it as these may dictate. This right is in its nature an unalienable right. It is unalienable, because the opinions of men, depending only on the evidence contemplated by their own minds cannot follow the dictates of other men: It is unalienable also, because what is here a right towards men, is a duty towards the Creator. It is the duty of every man to render to the Creator such homage and such only as he believes to be acceptable to him. This duty is precedent, both in order of time and in degree of obligation, to the claims of Civil Society. Before any man can be considerd as a member of Civil Society, he must be considered as a subject of the Governour of the Universe: And if a member of Civil Society, do it with a saving of his allegiance to the Universal Sovereign. We maintain therefore that in matters of Religion, no man’s right is abridged by the institution of Civil Society and that Religion is wholly exempt from its cognizance. True it is, that no other rule exists, by which any question which may divide a Society, can be ultimately determined, but the will of the majority; but it is also true that the majority may trespass on the rights of the minority...iii 12. Because the policy of the Bill is adverse to the diffusion of the light of Christianity. The first wish of those who enjoy this precious gift ought to be that it may be imparted to the whole race of mankind. Compare the number of those who have as yet received it with the number still remaining under the dominion of false Religions; and how small is the former! Does the policy of the Bill tend to lessen the disproportion? No; it at once discourages those who are strangers to the light of revelation from coming into the Region of it; and countenances by example the nations who continue in darkness, in shutting out those who might convey it to them. Instead of Levelling as far as possible, every obstacle to the victorious progress of Truth, the Bill with an ignoble and unchristian timidity would circumscribe it with a wall of defence against the encroachments of error.” -James Madison, Memorial and Remonstrance Against Religious Assessments17 The degree to which Madison’s religious activism and strongly-held convictions have been misconstrued in the centuries since, causing his inaccurate labeling as a deist,18 is in part due to his own tactfulness. Madison did not acknowledge that he had authored the Memorial and iii As an aside, Madison here makes an interesting argument: (1) that the will of the majority is essential to just governance of a society, and (2) the will of the majority can still oppress the rights of the minority per mob rule.

- 7. 7 Remonstrance Against Religious Assessments until 1826, after the completion of his presidency and political career. Madison, like Jefferson, waited until well after his political career had ended, a forty-year silence, to reveal what his religious convictions were.13 A New Theory: Madison Was a Baptist and Jefferson and Washington Were Jewish In explaining why such fervent advocates on behalf of religious freedom for the Danbury Baptists would conceal their religious convictions for decades, it seems most likely that both were secretly religious minorities that would have been unable to run for office under Virginia’s religious tests.iv Both Jews and Baptists were discriminated against under the Anglican state church of Virginia.10 Madison, seeing the injustices perpetrated against his fellow Baptists, whom he was constantly appearing in court to defend, realized he was needed more as a lawyer and politician than a minister. As such he consistently defended the Baptists but hid his own disagreement with Anglicanism out of fear it would be used against him. After all, under the Virginia religious tests he was overturning, he himself would have been unqualified to hold public office. Anglican opponents would have no doubt called foul for his overturning the state Anglican establishment while seeking to overturn his legislation on religious freedom and obstructing his pathway to the presidency, since at the time most of the country and its founders were Anglican. (Pyle and Davidson, pp. 66-71) Thus, Madison waited until the waning days of his life to reveal his role in passing the Memorial and Remonstrance Against Religious Assessments, guarding his Baptist iv This would explain why Madison went from pursuing an early career in ministry to instead seeking one in law and public service. To quote Gregory C. Downs, “Because of his opposition to the religious persecution of dissenters, Madison ‘repeatedly appeared in court of his own county to defend the Baptist nonconformists,’ and it was during this the period of his involvement in the defense of Baptists that Madison decided to choose a career in law and public service rather than the ministry.”

- 8. 8 convictions to the grave lest they be used to overturn his life’s work in fighting for their religious freedom.19 With Jefferson an equally strong case may be made for his being Jewish. Recent genetic research has raised the likelihood of Jewish ancestry for Thomas Jefferson.20 Jefferson’s wording in the Virginia Statute is hardly that of an atheist, deist, or agnostic, and his reverence for the scriptures is patently evident from his donation to help found the Virginia Bible Society; indeed Jefferson was one of the ten primary funders for the Virginia Bible Society. Jefferson as Governor of Virginia called for a statewide day of prayer, as a Virginia delegate to the Continental Congress recommended a state seal depicting a story from the Bible using the name ‘God,’ and when founding the University of Virginia at the end of his life designated space for chapel services, expecting students to attend religious services and religious schools neighboring or even on university property.v In 1804 Jefferson provided assurances to a Christian religious school in the Louisiana Territory that it would “receive the patronage of the government.” As concluded by David Barton in summarizing the evidence, “Thus the ‘wall of separation between church and state’ that Mr. Jefferson built at the University which he founded did not exclude religious education from that school… Neither at the State nor the federal level does Jefferson demonstrate any proclivity toward the obsessive secularization for which courts have used him.”21 Jefferson’s infamous ‘Jefferson Bible’ omitted the miracles of Jesus while emphasizing the eschatological discussions between Jesus and the Pharisees,22 a decision that makes perfect sense within the v Jefferson after becoming President in 1800 attended church every Sunday and allowed taxpayer-funded government musicians to assist in the worship services. In 1801 he urged local governments to make land available for Christian purposes, and in 1803 signed a treaty with the Kaskaskia tribe for erection of a church while funding a Catholic priest. Also in 1803 he signed three acts allocating government land for the purpose of Moravian missionaries to spread Christianity. (Barton, pp. 403-405)

- 9. 9 Jewish paradigm. Jewish opposition to Jesus, after all, has historically consisted of disagreement that Jesus is the Son of God; whereas a rabbinic eschatological discussion would be of immense value to the practicing Jew.23 Further evidence of Jefferson’s privately-held Jewish heritage is seen from his original rough draft of the Declaration of Independence, prior to Congress’ revisions.vi In the original, Jefferson disdainfully criticizes the “CHRISTIAN King of Great Britain,” a phrase removed by Congress.24 Several complaints in the original, thereafter altered by Congress to Jefferson’s intense displeasure, one can only imagine Jefferson originally wrote thinking of the Virginia religious testsvii preventing him from openly expressing his religious convictions.25 Like Madison, Jefferson would have been unable to reveal his Jewish heritage without endangering his lifetime of advocacy for the civil liberties of religious minorities. As a Jew, he would have been unable under Virginia law to run for public office; only by professing Anglicanism would he have been able to pursue reforms that discriminated against his fellow Jews. It may well be that Jefferson viewed himself as following in the footsteps of Moses who, as a child was hidden from the wrath of Pharaoh and secretly raised as an Egyptian prince, the standing he would need to advocate for his people’s freedom. (Exodus chs. 1-3, King James Version) As with Madison, Jefferson took the secret of his religious convictions to the grave, vi As an aside, Jefferson’s rough draft harshly criticized the institution of slavery, blaming it on the King of England, ironic given Jefferson’s own history of owning slaves, and perhaps the result of his intimate relationship with Sally Hemings. (Smith, 331-336) vii Including “it becomes necessary for a people to advance from that subordination in which they have hitherto remained… these facts have given the last stab to agonizing affection, and manly spirit bids us to renounce for ever these unfeeling brethren. we must endeavor to forget our former love for them… we might have been a free & great people together; but a communication of grandeur & of freedom it seems is below their dignity. be it so, since they will have it: the road to glory & happiness is open to us too; we will climb it in a separate state, and acquiesce in the necessity which pronounces our everlasting Adieu!”

- 10. 10 knowing that to disclose them would be to threaten a lifetime’s worth of work on behalf of American Jews’ civil liberties. As for Washington, who has fittingly been termed an ‘American Moses,’26 he used distinctive language typical of a practicing Jew in his letters. Three of the twenty-two addresses Washington gave to religious groups were to Jewish congregations (there were only 6 Jewish congregations in the U.S. at the time), and he used ‘explicit language’ in responding. Immediately following ratification of the Constitution in 1790, and just prior to ratification of the Bill of Rights in 1791, Washington uncharacteristically answered the Hebrew congregation in Newport with more than his typically terse response, authoring one of the strongest statements in support of religious freedom in American history. 27 In doing so, Washington quoted from Micah 4:4 about the “stock of Abraham” being able to “sit in safety under his own vine and fig tree,” a passage he quoted nearly four dozen times over the last half of his life. Fig trees held special relevance to the Jewish people. Per Dreisbach (2007), “The fig tree, like the grapevine, is a potent symbol for Jews… The images of a vine and a fig tree were rich with meaning for the prophet Micah's audience; they are symbols deeply ingrained in Jewish tradition.”28 Thus, Washington was likely sending a message to later generations that he himself was “of the stock of Abraham.” Washington’s actions played a major role in advancing religious freedom for Jews who had been discriminated against by state religious tests, producing in the words of Dreisbach (2007), Washington’s “greatest contribution to, and political innovation of, political society—the abandonment of religious toleration in favor of religious liberty.” (p. 322) Like Jefferson, Washington is best comprehended as a privately practicing Jew unable to publicly reveal his convictions without risking irreparable harm to his life’s work and the Jewish people. Like Jefferson and Madison, he could not disclose his status as a religious minority

- 11. 11 without jeopardizing the Virginia legislation passed in furtherance of Jewish religious freedom and risking public outcry over Jews and Baptists having been the primary opponents of Virginia’s Anglican state church. Washington’s recalcitrance at expressing overtly Christian sentiments has led to his branding, like Jefferson, as a Deist. Nonetheless, Deists in colonial and early post-colonial America were simply Jews that could not openly proclaim their faith due to religious tests prohibiting them from running for public office. To overturn such religious discrimination Jews had to secretly work within the dystopia without disclosing their true personal convictions. No doubt there was a broader population of Jews, Baptists, and other religious minorities that pretended Anglicanism to achieve civil liberties such as running for public office they would not otherwise have been privy to under Anglican colonial and early post-colonial laws; a possible factor for why Anglicanism appeared over-represented in the early United States but rapidly declined once the religious tests were revoked.29 In all probability Washington likely worked with Jefferson until 1791, privately coordinating with Jefferson to seek religious freedom for Virginia Jews, but, ever the cautious tactician, was more discrete than Jefferson in concealing his religious convictions. Indeed Washington was instrumental in assisting Madison to ensure creation of a Bill of Rights.30 Washington and Jefferson worked together until religious freedom was steadily achieved in Virginia, first by passage of Jefferson’s Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom on January 16, 1786, secondly by ratification of the U.S. Constitution on May 29, 1790 with its guarantee against religious tests, and thirdly by ratification of the Bill of Rights and 1st Amendment guaranteeing freedom of religion to all on December 15, 1791.viii viii However, the political differences between Washington, a Federalist, and Jefferson, an Anti-Federalist, were too great to long withstand their triumph for Jewish religious freedom. It is no coincidence that the relationship

- 12. 12 The Danbury Baptists Jefferson’s famous phrase ‘wall of separation’ from which stems the term ‘separation of church and state’ derives not from the U.S. Constitution or Bill of Rights, but his sympathetic letters to the Danbury Baptists. A 2003 analysis by David Barton determined that Jefferson was invoked directly or indirectly in 100% of Establishment Clause federal court cases. (Barton, 401) The 1801 letters occurred after decades of coordination between Jefferson and Madison defending Virginia Baptists from religious persecution. Jefferson’s association with the Baptists had gained him much-needed local allies, allowing for him, Washington, and Madison to coordinate on a cause dear to all of their hearts, religious freedom for their respective, secretly- held faiths, while simultaneously protecting him from charges of atheism made by his Federalist opponents.31 The letters between Jefferson and the Baptists were as follows: “The address of the Danbury Baptist Association in the State of Connecticut, assembled October 7, 1801. To Thomas Jefferson, Esq., President of the United States of America Sir, Among the many millions in America and Europe who rejoice in your election to office, we embrace the first opportunity which we have enjoyed in our collective capacity, since your inauguration , to express our great satisfaction in your appointment to the Chief Magistracy in the Unite States. And though the mode of expression may be less courtly and pompous than what many others clothe their addresses with, we beg you, sir, to believe, that none is more sincere. Our sentiments are uniformly on the side of religious liberty: that Religion is at all times and places a matter between God and individuals, that no man ought to suffer in name, person, or effects on account of his religious opinions, [and] that the legitimate power of civil government extends no further than to punish the man who works ill to his neighbor. But sir, our constitution of government is not specific. Our ancient charter, together with the laws made coincident therewith, were adapted as the basis of our government at the time of our revolution. And between Washington and Jefferson rapidly deteriorated from 1794-99 after their alliance of convenience to secure religious freedom for the Jewish people. (Higgenbotham, pp. 535-540)

- 13. 13 such has been our laws and usages, and such still are, [so] that Religion is considered as the first object of Legislation, and therefore what religious privileges we enjoy (as a minor part of the State) we enjoy as favors granted, and not as inalienable rights. And these favors we receive at the expense of such degrading acknowledgments, as are inconsistent with the rights of freemen. It is not to be wondered at therefore, if those who seek after power and gain, under the pretense of government and Religion, should reproach their fellow men, [or] should reproach their Chief Magistrate, as an enemy of religion, law, and good order, because he will not, dares not, assume the prerogative of Jehovah and make laws to govern the Kingdom of Christ. Sir, we are sensible that the President of the United States is not the National Legislator and also sensible that the national government cannot destroy the laws of each State, but our hopes are strong that the sentiment of our beloved President, which have had such genial effect already, like the radiant beams of the sun, will shine and prevail through all these States--and all the world--until hierarchy and tyranny be destroyed from the earth. Sir, when we reflect on your past services, and see a glow of philanthropy and goodwill shining forth in a course of more than thirty years, we have reason to believe that America's God has raised you up to fill the Chair of State out of that goodwill which he bears to the millions which you preside over. May God strengthen you for the arduous task which providence and the voice of the people have called you--to sustain and support you and your Administration against all the predetermined opposition of those who wish to rise to wealth and importance on the poverty and subjection of the people. And may the Lord preserve you safe from every evil and bring you at last to his Heavenly Kingdom through Jesus Christ our Glorious Mediator. Signed in behalf of the Association, Neh,h Dodge } Eph'm Robbins } The Committee Stephen S. Nelson }” “To messers. Nehemiah Dodge, Ephraim Robbins, & Stephen S. Nelson, a committee of the Danbury Baptist association in the state of Connecticut.32 Gentlemen The affectionate sentiments of esteem and approbation which you are so good as to express towards me, on behalf of the Danbury Baptist association, give me the highest satisfaction. my duties dictate a faithful and zealous pursuit of the interests of my constituents, & in proportion as they are persuaded of my fidelity to those duties, the discharge of them becomes more and more pleasing. Believing with you that religion is a matter which lies solely between Man & his

- 14. 14 God, that he owes account to none other for his faith or his worship, that the legitimate powers of government reach actions only, & not opinions, I contemplate with sovereign reverence that act of the whole American people which declared that their legislature should ‘make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof,’ thus building a wall of separation between Church & State. Adhering to this expression of the supreme will of the nation in behalf of the rights of conscience, I shall see with sincere satisfaction the progress of those sentiments which tend to restore to man all his natural rights, convinced he has no natural right in opposition to his social duties. I reciprocate your kind prayers for the protection & blessing of the common father and creator of man, and tender you for yourselves & your religious association, assurances of my high respect & esteem. Th Jefferson Jan. 1. 1802.”33 Rather than writing for a secular purpose, as has been commonly concluded, Jefferson was simply affirming his long-held alliance with Madison’s Baptists, opposing Virginia’s religious tests which had been used to discriminate against Baptists and Jews alike. In stark contrast to the openly Christian wording used by the Baptists, Jefferson subtly emphasized the shared beliefs of Jews and Baptists in a “common father and creator of man.” Undoubtedly Jefferson, like Washington and Madison, was growing tired by this time of hiding his personal convictions and was increasingly dropping hints about his own Jewish beliefs.ix Jefferson’s authorship of his letter to the Danbury Baptists was in part a political tack designed, per his correspondence with Massachusetts Attorney General Levi Lincoln, not only to repudiate the notion of governmental religious tests, but also to defend himself from accusations that he supported political fastings and prayers, at a time when the issue was key to his election ix Jefferson had, as previously mentioned, openly referenced a Creator as the source of inalienable rights in the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, helped found the Virginia Bible Society, and as Governor of Virginia called for a statewide day of prayer while authoring a law titled ‘A bill for appointing days of public fasting and thanksgiving.’ Even after 1820 upon founding the University of Virginia he encouraged university students to attend religious services on university grounds. (Barton, p. 403-409)

- 15. 15 chances. Jefferson told Lincoln that he wrote the letter in part for the purpose of “saying why I do not proclaim fastings & thanksgivings, as my predecessors did.” Jefferson at the time sought to damage his political opponent for the presidency, John Adams, by portraying him as a Presbyterian who would implement strict religious requirements unpopular with the broader Christian population.34 Given that Jefferson had himself passed legislation as Virginia Governor mandating such fasting and prayer, he sought to protect himself from charges of hypocrisy. Jefferson’s original draft letter to the Danbury Baptists included more openly religious language which he carefully revised to produce the political impact he desired.35 Jefferson’s “satisfaction” at guarantees of universal religious freedom undoubtedly derived from his private Jewish convictions, and the repeal of Virginia’s religious tests that had forced him, Washington, and Madison to conceal their personal religious beliefs for three lifetimes; unable to run for public office had they been open about their faith. As such, Jefferson no doubt savored this moment of celebration with his Baptist allies, even as he wittingly underlined the distinctions between his Jewish faith and that of his Christian friends. Pre-Lockean Sources for Inalienable Rights The phrase ‘wall of separation’ was not originated by Jefferson, but by Roger Williams, founder of the colony of Rhode Island in 1636, first Baptist church on American shores, and America’s first anti-slavery organization.36 Williams was also an early advocate for peaceful relations with Native American tribes who coexisted peacefully with local tribes such as the Narragansetts for decades, until they attacked without provocation, forcing Williams to turn military commander and defeat them in battle.37 Although John Locke’s ‘Two Treatises of Government,’ authored in 1689, have been commonly attributed as the primary source of inspiration for modern democracy and civil liberties, as expressed by Thomas Jefferson and

- 16. 16 James Madison in the Bill of Rights and U.S. Constitution, Roger Williams authored ‘The Bloudy Tenent of Persecution for Cause of Religious Conscience’ (1644) over 40 years before Locke’s treatises, urging religious freedom on a Biblical basis. “according to the verity of holy Scriptures, &c. mens consciences ought in no sort to be violated, urged or constrained. And whensoever men have attempted any thing by this violent course, whether openly or by secret means, the issue hath been pernicious, and the cause of great and wonderful innovations in the principallest and mightiest Kingdoms and Countries, &c.” -Roger Williams, The Bloudy Tenent of Persecution for Cause of Conscience38 Williams provided four primary arguments to convince the British Parliament to allow his experiment of religious freedom to take place, first a Biblical basis, secondly reference to rulers, thirdly the quotations of famous writers, and fourthly the words of Catholic papists. TABLE 2. Roger Williams’ Sources for Religious Freedom CATEGORY SOURCES BIBLICAL Mt. 5; 13:30-38; 15:14; 20:6; Lk. 9:54-55; 2 Ti. 2:24; Is. 2:4; 11:9; Mi. 4:3-4; 2 Co. 10:4; 1 Co. 6:9; 1 Pe. 2:20. RULERS - King James 1609 Majesties Speech at Parliament. - King James Highness Apologie, pp. 4, 60. - Stephen King of Poland statements. - King of Bohemia statements. WRITERS - Hillarie Against Auxentius. - Tertullian Ad. Scapulum. - Jerome in Proaem. Lib. 4 in Jeremiam. - Brentius. - Luther in Book of the Civill Magistrate. PAPISTS - K. James His Reigne. Although Gilpin claims that “Williams and Jefferson had constructed their respective walls of separation for quite different purposes… Williams’s wall fell into obscurity, Jefferson’s rose to new influence in the mid-twentieth century,”34 such a conclusion neglects the broader impacts Williams’ wall of separation had on a more influential colonial founder, William Penn. Penn likely devised the Province of Pennsylvania’s 1682 Frame of Government with its

- 17. 17 guarantees of religious freedom on the basis of Williams’ earlier model.39 Article XXXV of the Frame’s Laws Agreed Upon in England provided what at the time was an unusually broad guarantee of religious freedom to all believers in God, including Jews and Muslims, declaring “That all persons living in this province, who confess and acknowledge the one Almighty and eternal God, to be the Creator, Upholder and Ruler of the world; and that hold themselves obliged in conscience to live peaceably and justly in civil society, shall, in no ways, be molested or prejudiced for their religious persuasion, or practice, in matters of faith and worship, nor shall they be compelled, at any time, to frequent or maintain any religious worship, place or ministry whatever.”x While it is easy to dismiss Williams’ wall of separation as the work of a small, isolated colony, as Gilpin does, Penn’s Frame provides the missing link between such a concept and Jefferson’s use of it over 150 years later. Penn’s Province of Pennsylvania, in contrast to the diminutive colony of Rhode Island, was vast, encompassing the modern-day states of Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware; as such four of the original thirteen states had Biblically-based walls of separation guaranteeing religious freedom per the Christian principles of Penn and Williams. Furthermore, Penn’s Quakers had an outsized impact on the American Revolution, which is why the Constitutional Convention was held in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The Quakers in Pennsylvania outlawed slavery on March 1, 1780 and formed much of the early post-colonial opposition to slavery leading up to the Civil War. Undoubtedly the work of Williams influenced John Locke’s treatises, and proved the basis for Jefferson’s later reuse of Williams’ wall of separation. Jefferson, as a studious lawyer, x Nonetheless, Penn’s Frame was explicitly Christian in nature, quoting the Bible’s book of Romans in the Preface, and prohibiting work on Sundays “according to the good example of the primitive Christians.” (Laws Agreed Upon in England, XXXVI)

- 18. 18 was certainly aware of Penn’s Frame of Government. As such the concept of inalienable, God- given rights that features prominently in Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence, Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, and Madison’s Memorial and Remonstrance Against Religious Assessments traces back to the earlier governmental frame produced by Williams. A Lost Work by Martin Luther As mentioned, Williams acknowledged even earlier works and monarchial decrees, quoting them to establish a basis of authority for the unprecedented religious freedom his colony was providing. The British Parliament initially objected to Williams’ government, and Williams’ careful research certainly played a role in persuading Parliament. Williams, to persuade Parliament, proposed that his colony be, in the words of John M. Barry, “an experiment in soul liberty, all England could watch the results.”40 This assuredly proved in part the inspiration for Penn’s 1682 “holy experiment,” as did the governments of Locke and Shaftesbury in the Carolinas which provided religious freedom to all save atheists.41 The most thoroughly quoted extra-Biblical source referenced by Roger Williams is a lost work by the famous reformer Martin Luther, referred to by Williams as ‘Booke of the Civill Magistrate.’ This is seemingly his 1523 book, ‘Of the Dignity and Office of the Civil Magistrate.’42 It seems likely that the 1646 Westminster Confession of Faith drew upon Luther’s material, given the correlation between Chapter 23 (‘Of the Civil Magistrate’) and Luther’s work referenced in Roger Williams’ ‘Bloudy Tenent.’ As such, it is likely that a work equivalent to Locke’s two treatises was produced over 260 years earlier by Martin Luther. Thus, the origin of a ‘wall of separation’ is far more ancient than has been conventionally acknowledged. “Luther in his Booke of the Civill Magistrate saith; The Lawes of the Civill Magistrates government extends no further then over the body or goods, and to that which is externall: for over the soule God will not suffer any man to rule:

- 19. 19 onely he himselfe will rule there. Wherefore whosoever doth undertake to give Lawes unto the Soules and Consciences of Men, he usurpeth that government himselfe which appertaineth unto God, &c. Therefore upon 1 Kings 5. 10 In the building of the Temple there was no sound of Iron heard, to signifie that Christ will have in his Church a free and a willing People, not compelled and constrained by Lawes and Statutes. Againe he saith upon Luk. 22. 11 It is not the true Catholike Church, which is defended by the Secular Arme or humane Power, but the false and feigned Church, which although it carries the Name of a Church yet it denies the power thereof. And upon Psal. 17. 12 he saith: For the true Church of Christ knoweth not Brachium saeculare, which the Bishops now adayes, chiefly use. Againe, in Postil. Dom. 1. post Epiphan.13 he saith: Let not Christians be commanded, but exhorted: for, He that willingly will not doe that, whereunto he is friendly exhorted, he is no Christian: wherefore they that doe compell those that are not willing, shew thereby that they are not Christian Preachers, but Worldly Beadles. Againe, upon 1 Pet. 3. 14 he saith: If the Civill Magistrate shall command me to believe thus and thus: I should answer him after this manner: Lord, or Sir, Looke you to your Civill or Worldly Government, Your Power extends not so farre as to command any thing in Gods Kingdome: Therefore herein I may not heare you. For if you cannot beare it, that any should usurpe Authoritie where you have to Command, how doe you thinke that God should suffer you to thrust him from his Seat, and to seat your selfe therein?” -Roger Williams, The Bloody Tenent of Persecution for Cause of Conscience

- 20. 20 Sources 1 Pyle, R.E. & Davidson, J.D. (2003, March). “The Origins of Religious Stratification in Colonial America.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 42(1): 60-65. 2 N.a. (2019). “Religion and the Founding of the American Republic.” Library of Congress. 3 The Avalon Project (1776). “Constitution of Delaware.” Yale Law School, Lillian Goldman Law Library. 4 The Avalon Project (1777, February 5). “Constitution of Georgia.” Yale Law School, Lillian Goldman Law Library. 5 The Avalon Project (1776, November 11). “Constitution of Maryland.” Yale Law School, Lillian Goldman Law Library. 6 The Avalon Project (1776). “Constitution of New Jersey.” Yale Law School, Lillian Goldman Law Library. 7 The Avalon Project (1776, December 18). “Constitution of North Carolina.” Yale Law School, Lillian Goldman Law Library. 8 The Avalon Project (1776, September 28). “Constitution of Pennsylvania.” Yale Law School, Lillian Goldman Law Library. 9 The Avalon Project (1778, March 19). “Constitution of South Carolina.” Yale Law School, Lillian Goldman Law Library. 10 The Avalon Project (1777, July 8). “Constitution of Vermont.” Yale Law Library, Lillian Goldman Law Library. 11 Downs, G.C. (2007, Fall). “Religious Liberty that Almost Wasn't: On the Origin of the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment.” University of Arkansas at Little Rock Law Review 30(1): 20-21. 12 Heyrman, C.L. (2019). “The Separation of Church and State from the American Revolution to the Early Republic.” National Humanities Center. 13 Schwartz, S.A. (2000, April 30). “George Mason: Forgotten Founder, He Conceived the Bill of Rights.” Smithsonian Institution. 14 Solomon, S.D. (2018, February 2). “Madison-Jefferson Letters on Advisability of a Bill of Rights, 1787-1789.” First Amendment Watch, New York University. 15 Penn, W. (1701, October 28). “Charter of Privileges Granted by William Penn, Esq. to the Inhabitants of Pennsylvania and Territories.” Yale Law School, Lillian Goldman Law Library. 16 Jefferson, T. (1779, June 18). “82. A Bill for Establishing Religious Freedom.” National Archives. 17 Madison, J. (1785, June 20). “Memorial and Remonstrance Against Religious Assessments.” National Archives. 18 Hutson, J. (2017, September 19). “James Madison and the Social Utility of Religion: Risks vs. Rewards.” Library of Congress. 19 Scarberry, M.S. (2008). “John Leland and James Madison: Religious Influence on the Ratification of the Constitution and on the Proposal of the Bill of Rights.” pp. 735-737. Pepperdine University School of Law. 20 Palmie, S. (2007, May). “Genomics, Divination, ‘Racecraft.’” American Ethnologist 34(2): 205-222. 21 Barton, D. (2003). “The Image and the Reality: Thomas Jefferson and the First Amendment.” Notre Dame J.L. Ethics & Pub. Pol’y 17(2): 403-410, 448. 22 Mabee, C. (1979, December). “Thomas Jefferson’s Anti-Clerical Bible.” Historical Magazine of the Protestant Episcopal Church 48(4): 473-481. 23 Hurtado, L.W. (1999, April). “Pre-70 CE Jewish Opposition to Christ Devotion.” The Journal of Theological Studies 50(1): 35-58. 24 Smith, M.A. (2009, May). “Teaching Jefferson.” The History Teacher 42(3): 329-343. 25 Jefferson, T. (1776, June 28). “Jefferson’s ‘Original Rough Draught’ of the Declaration of Independence.” Library of Congress. 26 Hay, R.P. (1969). “George Washington: American Moses.” American Quarterly 21(4): 780-791. doi:10.2307/2711609 27 Boller Jr., P.F. (1962, Spring). “George Washington and the Jews.” Southwest Review 47(2): 123-125. Sarna, J.D. (2012). “To Bigotry No Sanction: George Washington and Religious Freedom.” National Museum of American Jewish History. 28 Dreisbach, D.L. (2007, September). “The ‘Vine and Fig Tree’ in George Washington's Letters: Reflections on a Biblical Motif in the Literature of the American Founding Era.” Anglican and Episcopal History 76(3): 308-309.

- 21. 21 29 Holmes, D.L. (1978, September). “The Episcopal Church and the American Revolution.” Historical Magazine of the Protestant Episcopal Church 47(3): 261-291. Historical Society of the Episcopal Church. 30 Higgenbotham, D. (2003, Winter). “Virginia's Trinity of Immortals: Washington, Jefferson, and Henry, and the Story of Their Fractured Relationships.” Journal of the Early Republic 23(4): 525. 31 Dreisbach, D.L. (1999, October). “Thomas Jefferson and the Danbury Baptists Revisited.” The William and Mary Quarterly 56(4): 807-810. 32 Dodge, N.; Robbins, E.; & Nelson, S.S. (1801, October 7). “To Thomas Jefferson from the Danbury Baptist Association.” National Archives. 33 Jefferson, T. (1802, January 1). “Jefferson’s Letter to the Danbury Baptists.” Library of Congress. 34 Hutson, J. (1998, June). “A Wall of Separation: FBI Helps Restore Jefferson’s Obliterated Draft.” Library of Congress. 35 Jefferson, T. (1802, January 1). “Jefferson’s Letter to the Danbury Baptists: The Draft and Recently Discovered Text.” Library of Congress. 36 Gilpin, W.C. (2010, December). “Building the ‘Wall of Separation’: Construction Zone for Historians.” Church History 79(4): 871-880. Howe, M.D. (1965). “The Garden and the Wilderness: Religion and Government in American Constitutional History.” American Political Science Review 62(2): 597-599. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 37 Cummins, J. (2006). "History's Great Untold Stories: Larger Than Life Characters and Dramatic Events That Changed the World." Murdoch Books. 38 Williams, R. (1644). “The Bloudy Tenent of Persecution for Cause of Conscience.” Liberty Fund. 39 Penn, W. (1682, May 5). “Frame of Government of Pennsylvania.” Yale Law School, Lillian Goldman Law Library. 40 Barry, J.M. (2012, January). “God, Government and Roger Williams’ Big Idea.” Smithsonian Magazine. 41 Trueblood, B.F. (1895, January). “William Penn’s Holy Experiment in Civil Government.” The Advocate of Peace 57(1): 6. Kessler, S. (1985, Spring). “John Locke’s Legacy of Religious Freedom.” Polity 17(3): 494-495. University of Chicago Press. 42 Gardner, T. (1740). “An Historical Account of the Lives of Dr. Martin Luther Mr. John Calvin Who Were the Great Instruments of Establishing the Protestant Religion, 2nd ed.” p. 28. London: Cowley’s Head.