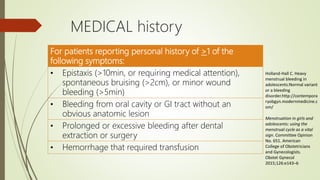

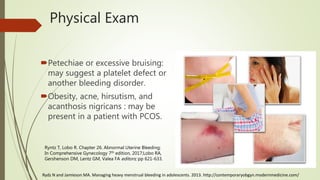

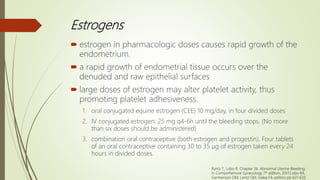

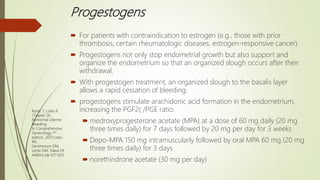

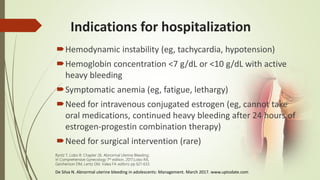

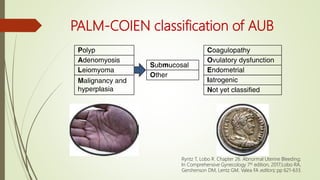

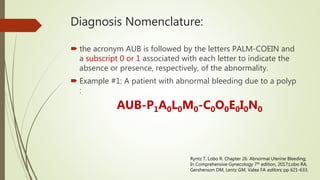

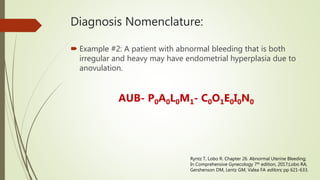

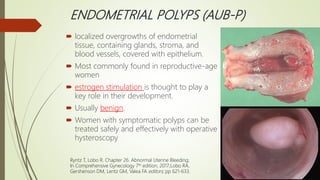

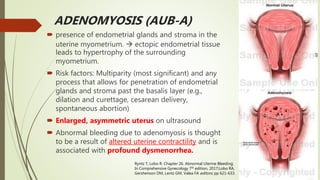

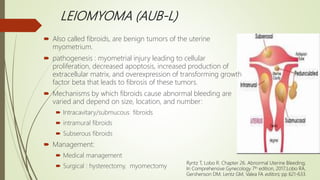

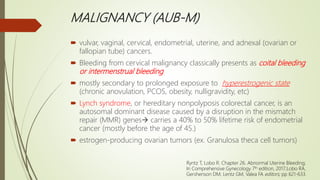

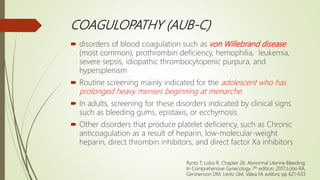

The document discusses abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB), a common health concern among women characterized by heavy menstrual bleeding, irregular cycles, and prolonged duration. It provides definitions, classifications, diagnostic approaches, examples of underlying causes including endometrial polyps, adenomyosis, malignancies, coagulopathies, and ovulatory dysfunction, as well as management strategies. Treatment options vary based on the specific cause of AUB and may include medical and surgical interventions.

![CH ristocetin cofactor should be obtained to rule out a coagula-

Adults with HMB and h/o either

One of the following Two of the following

Testing

Figure 26.6 Diagnostic approach to adults with abnormal uterine

bleeding due to coagulopathy. (Data from Kouides PA, Conard J,

Peyvandi F, et al. Hemostasis and menstruation: appropriate investi -

gation for underlying disorders of hemostasis in women with exces -

sive menstrual bleeding. Fertil Steril. 2005;84[5]:1345-1351.)

100 1000

al blood loss (mL)

5

ratio of endogenous concentra -

prostaglandin E and menstrual

endometrium; persistent endo -

H, Kelly RW, et al. The synthesis

roliferative endometrium. JClin

289.)

Ryntz T, Lobo R. Chapter 26. Abnormal Uterine Bleeding;

In Comprehensive Gynecology 7th edition, 2017;Lobo RA,

Gershenson DM, Lentz GM, Valea FA editors; pp 621-633.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/aub-180620141421/85/Abnormal-Uterine-Bleeding-15-320.jpg)