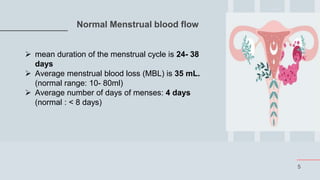

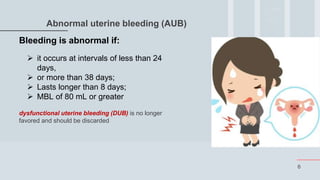

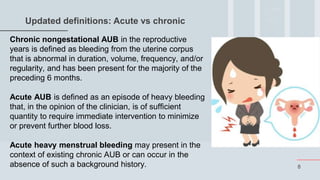

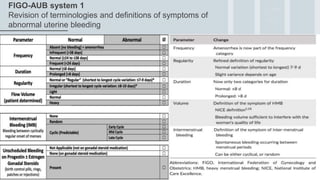

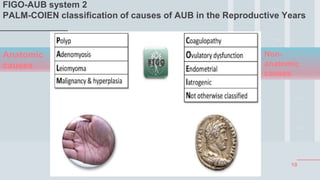

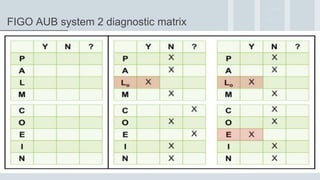

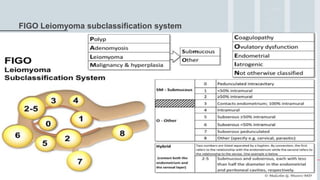

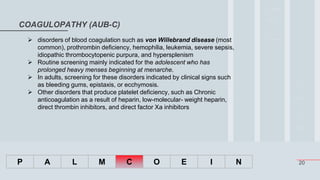

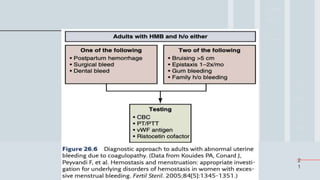

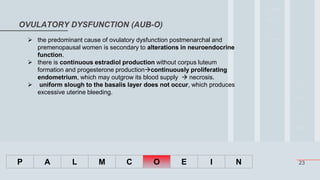

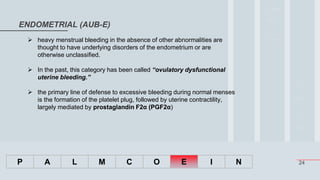

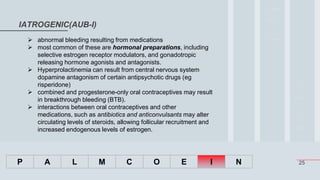

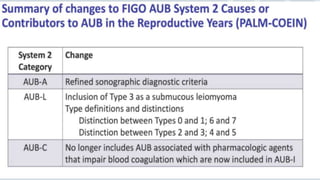

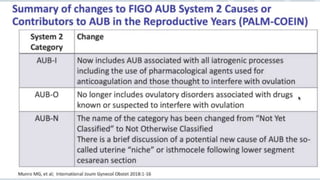

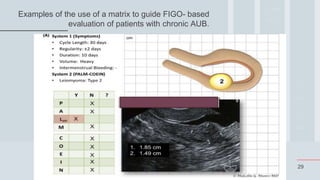

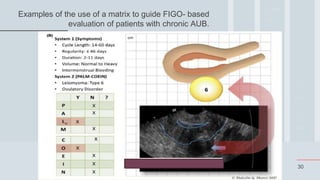

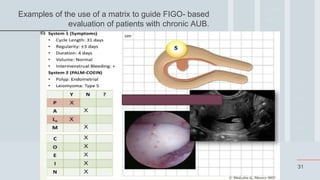

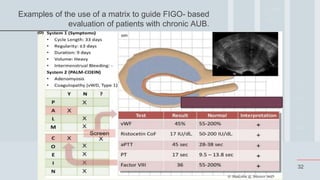

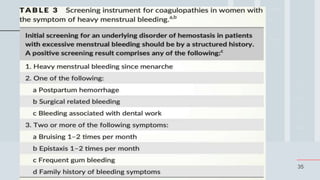

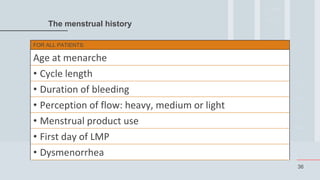

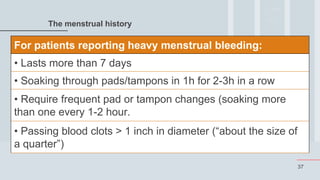

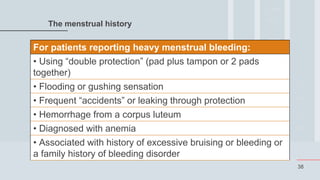

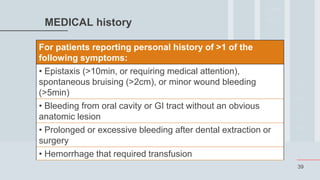

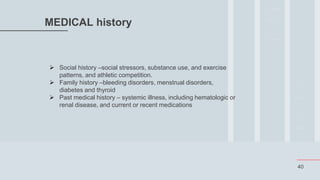

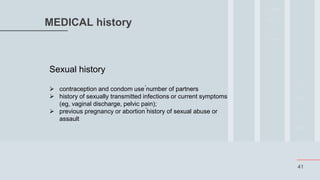

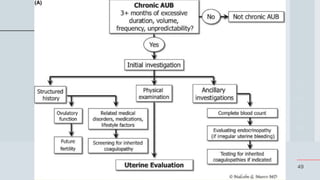

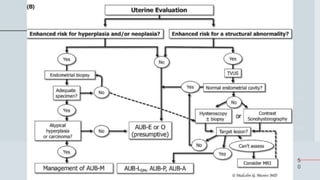

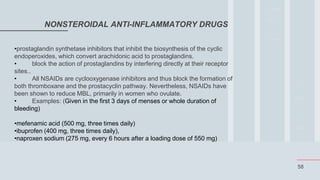

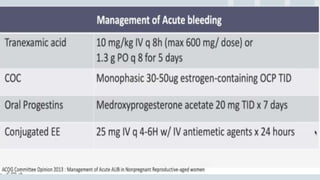

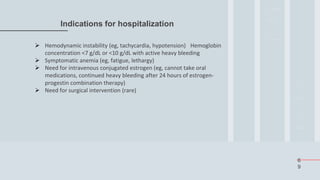

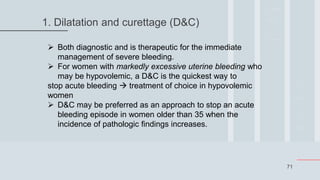

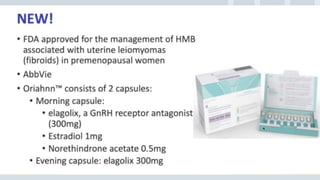

This document outlines the FIGO 2018 updates on the classification and management of abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB). It begins with definitions of normal menstrual bleeding and criteria for abnormal bleeding. It then describes the two FIGO systems - one revising terminology and definitions of symptoms, and the other classifying causes of AUB using the PALM-COEIN matrix. Various pathophysiologies are discussed for each cause. Evaluation involves history, exam, labs, and imaging. Treatment depends on the cause and severity, with goals of stabilization and prevention of long-term consequences. Medical management typically involves combined hormonal contraceptives to stabilize the endometrium.