The document discusses key concepts from Einstein's special theory of relativity, including:

1) Frames of reference and the distinction between inertial and non-inertial frames. The laws of motion only hold in inertial frames.

2) The postulates of special relativity - that the laws of physics are the same in all inertial frames, and that the speed of light is constant.

3) Consequences of these postulates, including Lorentz transformations, length contraction, time dilation, and the relativity of simultaneity.

4) Experiments that motivated relativity, like the Michelson-Morley experiment, and equations like Lorentz transformations that were developed to be consistent with the postulates

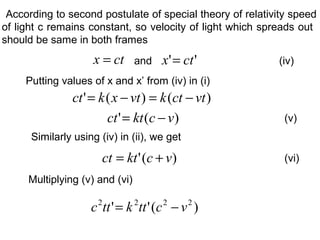

![The transformation equations of x and x’ can be written as

)(' vtxkx −=

where k is a constant of proportionality and is independent of x

and t.

The inverse relation can be written as

)''( vtxkx += (ii)

(i)

Here . Putting value of x’ from (i) in (ii)'tt ≠

]')([ vtvtxkkx +−=

'vtkvtkx

k

x

+−=

kt

v

kx

kv

x

t +−='

−−= 2

1

1'

kv

kx

kttor (iii)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/relativity-160130074831/85/Relativity-11-320.jpg)

![From equation (i)

(v)

[ ]

22

2

2

2

1

)1(

/)(

11

cuv

cvu

c

u

+

+

−=−

2

2

2

1

1

1

cuv

cuv

m

m

−

+

=

22

2222

)1(

)1)(1(

cuv

cvcu

+

−−

=

Similarly from equation (ii)

=− 2

2

2

1

c

u

22

2222

)1(

)1)(1(

cuv

cvcu

−

−−

(vi)

Dividing equation (vi) by (v)

22

22

22

1

22

2

)1(

)1(

1

1

cuv

cuv

cu

cu

−

+

=

−

−](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/relativity-160130074831/85/Relativity-29-320.jpg)

![(vii)

From equation (iv) and (vii)

From (viii), it is clear that LHS and RHS are independent of

each other. This is true when each equal to a constant.

)1(

)1(

1

1

2

2

22

1

22

2

cuv

cuv

cu

cu

−

+

=

−

−

22

1

22

2

2

1

1

1

cu

cu

m

m

−

−

=

[ ] [ ]22

22

22

11 11 cumcum −=− (viii)

[ ] [ ] omcumcum =−=− 22

22

22

11 11

where is the rest mass of the bodyom](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/relativity-160130074831/85/Relativity-30-320.jpg)

![(viii)

Integrating equation (vii)

2

0

2

0

2

][ cmmcmmcEK −=−=

∫∫ =

m

m

E

K dmcdE

K

0

2

0

2

0

2

cmEmc K +=

From equation (viii), we find that is the total energy. It is

the sum of kinetic and rest mass energy

2

mc

2

mcE =

This relation is called Einstein’s mass energy relation.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/relativity-160130074831/85/Relativity-35-320.jpg)

![)(1 222

2

0

Ecp

cm

E

−

=

)(1 222

42

02

Ecp

cm

E

−

=

42

0

2222

])(1[ cmEcpE =−

42

0

222

cmcpE =−

2242

0

2

cpcmE +=

2242

0 cpcmE +=](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/relativity-160130074831/85/Relativity-37-320.jpg)