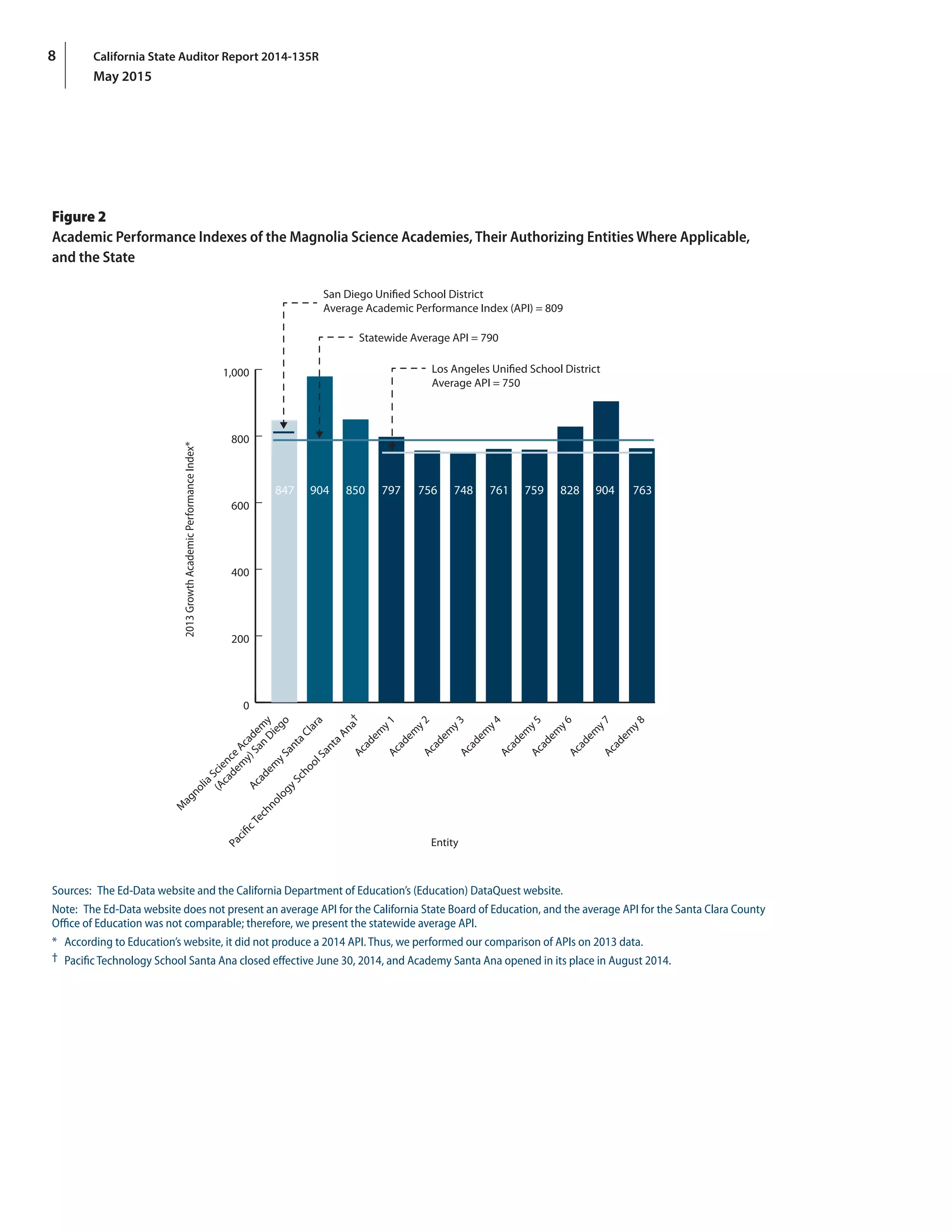

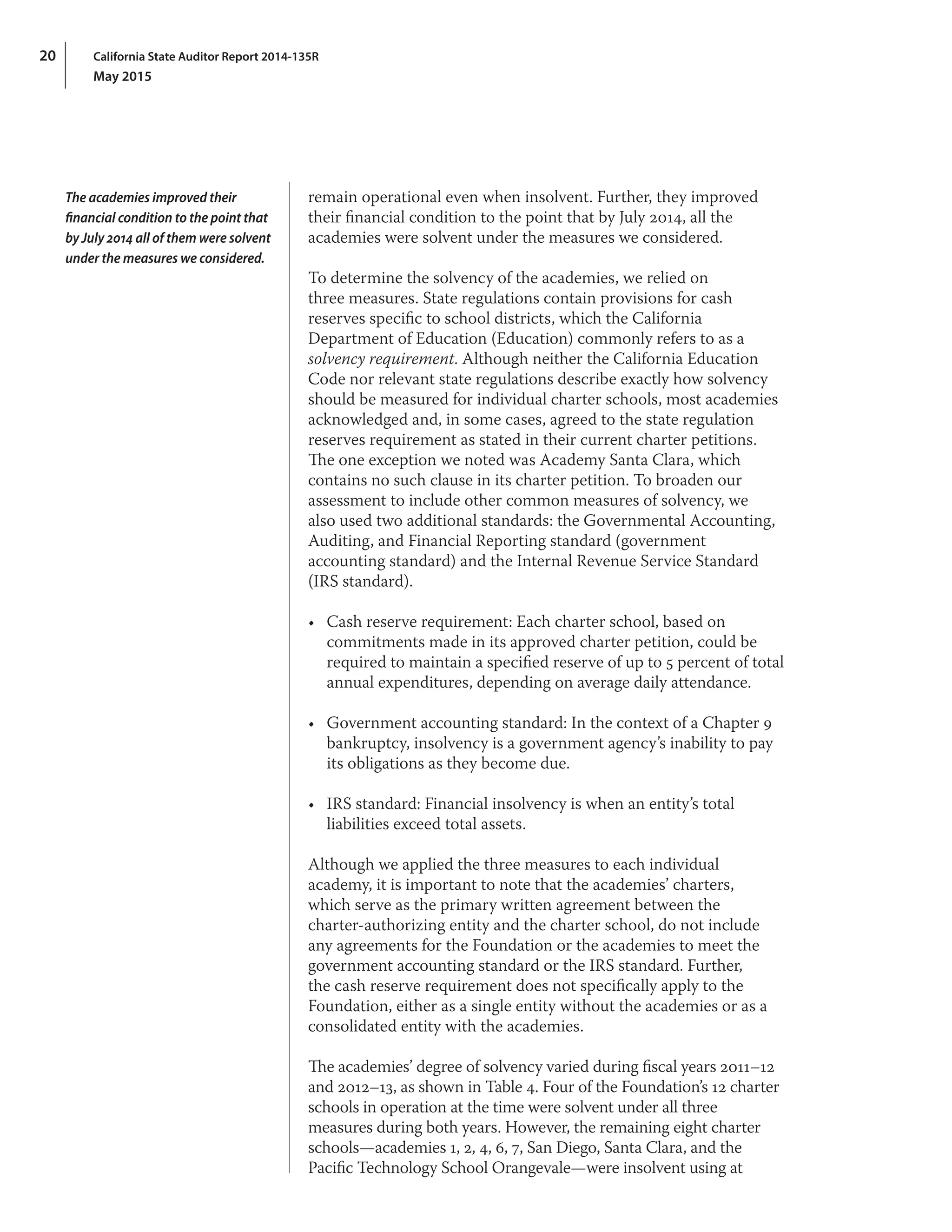

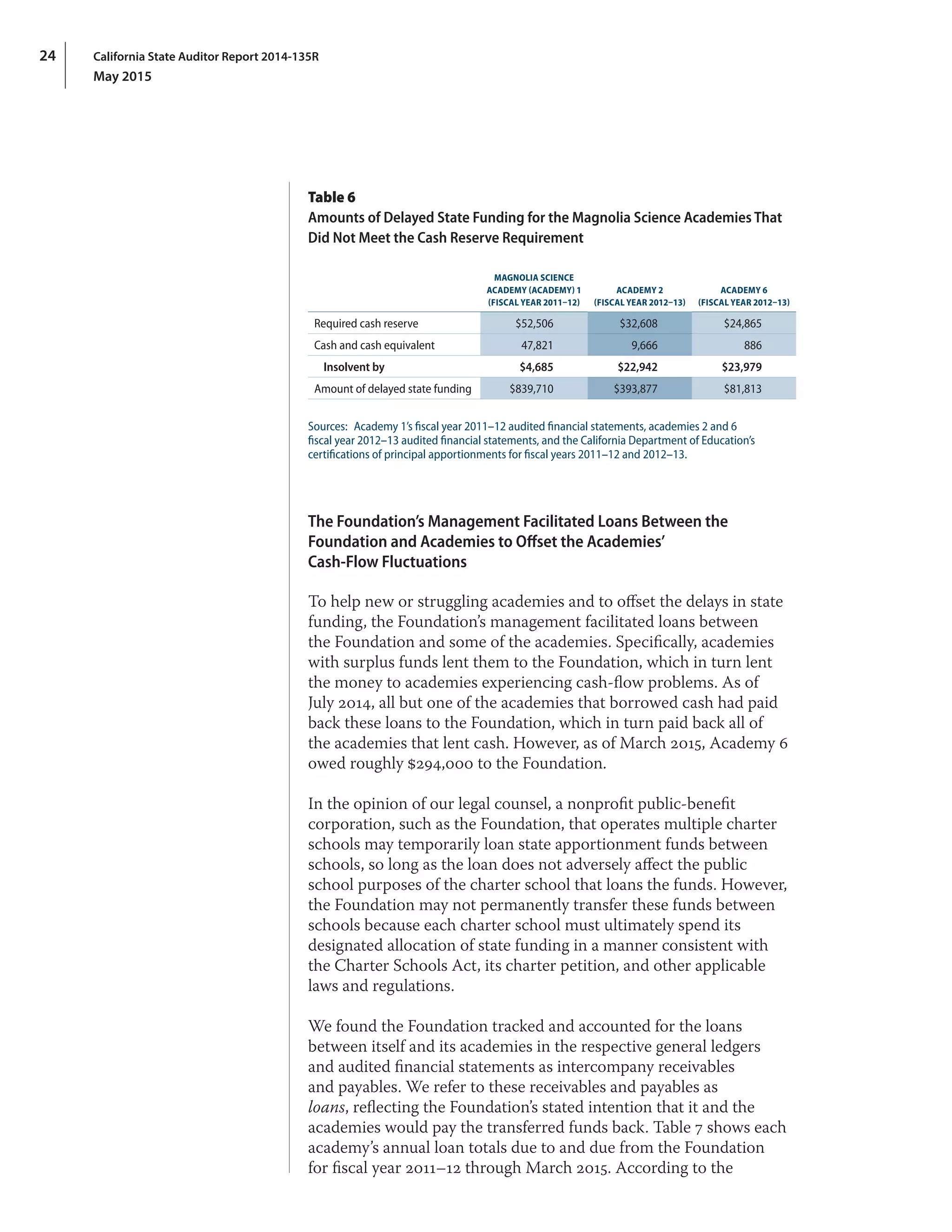

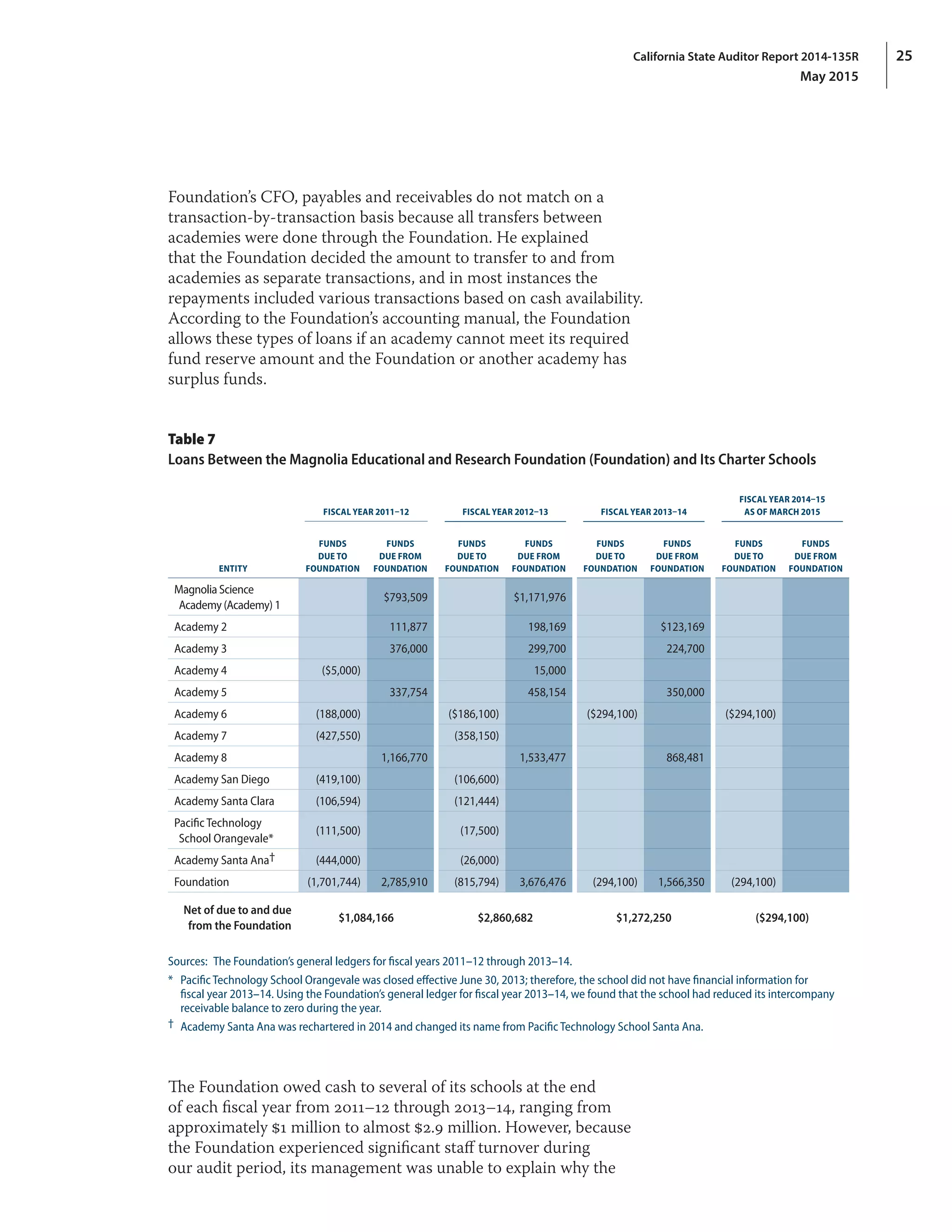

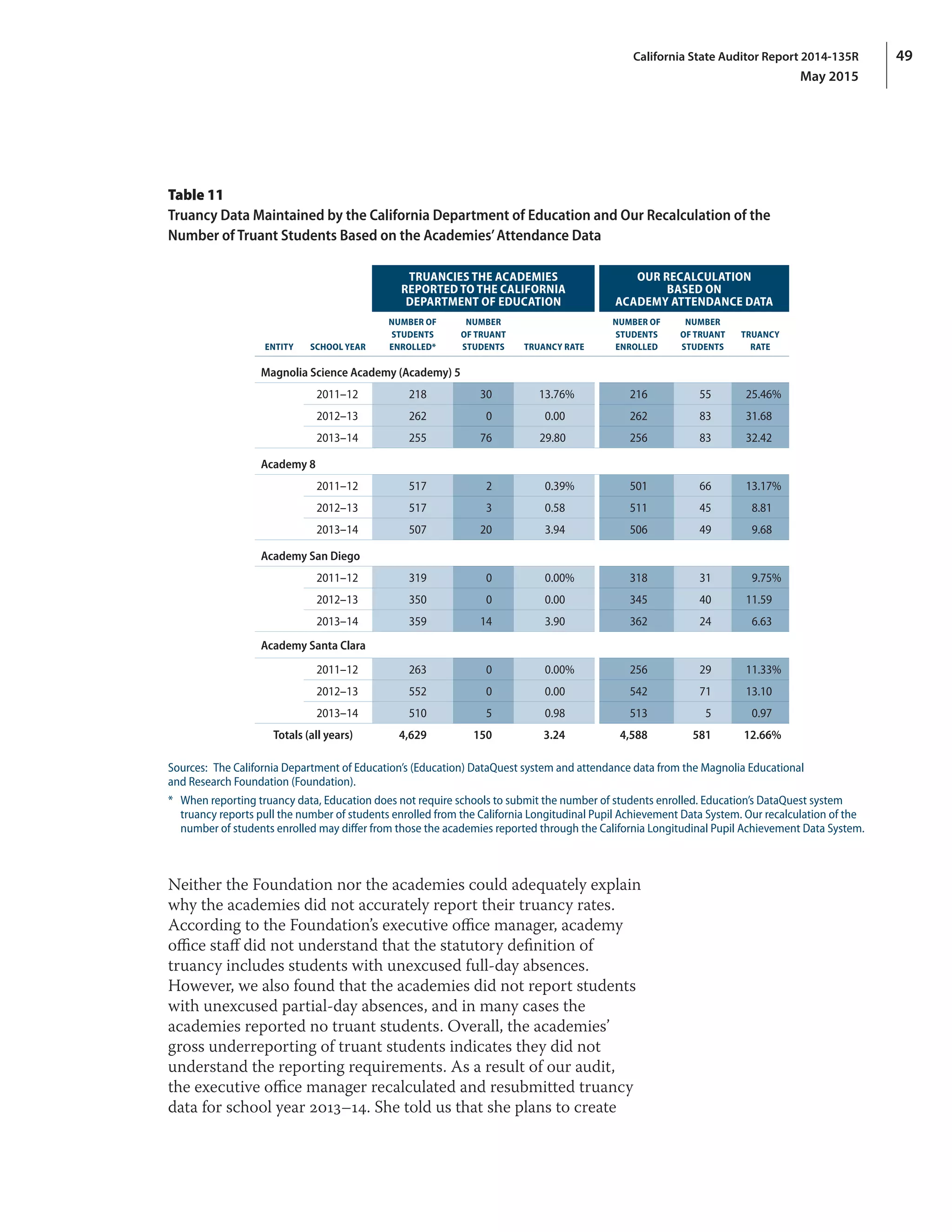

The California State Auditor's report on Magnolia Science Academies highlights that, while the financial condition of the academies has improved, there remain significant weaknesses in the foundation's financial management practices. The foundation facilitated loans to financially struggling academies, which were largely beneficial, yet many transactions lacked proper authorization or documentation, raising concerns about fiscal accountability. Additionally, the Los Angeles Unified School District may have prematurely rescinded charter renewals for two academies based on incomplete information, leading to subsequent legal actions and a settlement that resulted in the renewal of those charters.