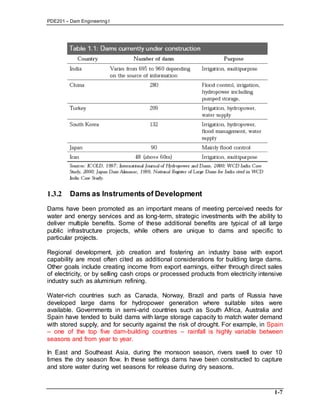

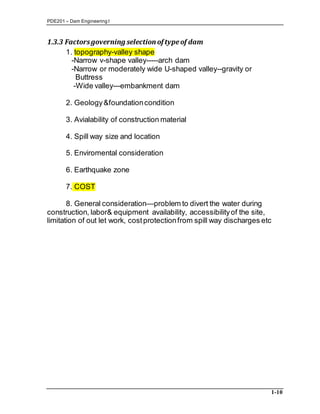

This document provides an overview of dam engineering and the history of dam construction. It discusses that dams were first constructed over 8,000 years ago for irrigation purposes. The 20th century saw a rapid increase in large dam construction, with over 45,000 large dams built globally by the end of the century. China alone has built around 22,000 large dams, accounting for nearly half of the world's total. Dams were promoted as a means to meet water and energy needs and foster regional development. Factors governing dam type selection include valley topography, geology and foundation conditions, availability of construction materials, and environmental and cost considerations.