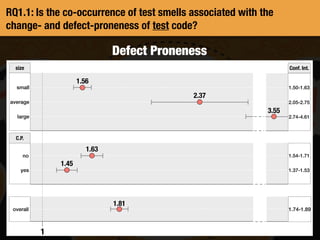

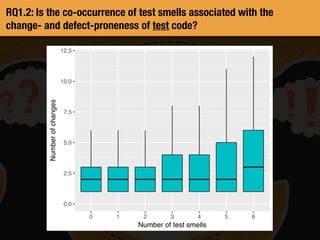

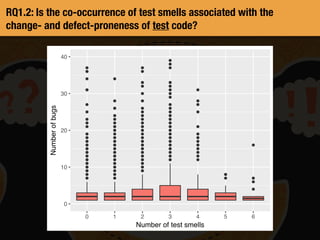

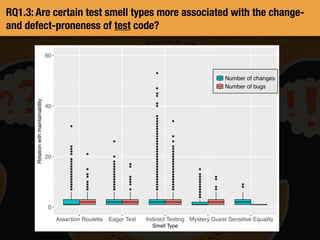

The document summarizes a study on the relationship between test smells and software code quality. The study investigates whether the presence of test smells is associated with increased change/defect-proneness of test code and defect-proneness of production code. The methodology examines over a million test cases across 221 releases of 10 open source projects. Test smells are detected and their correlation with change/defect metrics is analyzed to understand their impact on code quality. Preliminary results indicate tests with smells are more change/defect-prone and certain smells like Indirect Testing are strongly associated with change-proneness.

![Refactoring Test Code

Arie van Deursen Leon Moonen Alex van den Bergh Gerard Kok

CWI Software Improvement Group

The Netherlands The Netherlands

http://www.cwi.nl/~{arie,leon}/ http://www.software-improvers.com/

{arie,leon}@cwi.nl {alex,gerard}@software-improvers.com

ABSTRACT

Two key aspects of extreme programming (XP) are unit

testing and merciless refactoring. Given the fact that the

ideal test code / production code ratio approaches 1:1, it is

not surprising that unit tests are being refactored. We found

that refactoring test code is different from refactoring pro-

duction code in two ways: (1) there is a distinct set of bad

smells involved, and (2) improving test code involves ad-

ditional test-specific refactorings. To share our experiences

with other XP practitioners, we describe a set of bad smells

that indicate trouble in test code, and a collection of test

refactorings to remove these smells.

Keywords

Refactoring, unit testing, extreme programming.

1 INTRODUCTION

“If there is a technique at the heart of extreme program-

ming (XP), it is unit testing” [1]. As part of their program-

ming activity, XP developers write and maintain (white

box) unit tests continually. These tests are automated,

written in the same programming language as the produc-

tion code, considered an explicit part of the code, and put

under revision control.

The XP process encourages writing a test class for every

class in the system. Methods in these test classes are used

to verify complicated functionality and unusual circum-

stances. Moreover, they are used to document code by ex-

plicitly indicating what the expected results of a method

should be for typical cases. Last but not least, tests are

added upon receiving a bug report to check for the bug and

to check the bug fix [2]. A typical test for a particular

method includes: (1) code to set up the fixture (the data

used for testing), (2) the call of the method, (3) a compari-

son of the actual results with the expected values, and (4)

code to tear down the fixture. Writing tests is usually sup-

ported by frameworks such as JUnit [3].

The test code / production code ratio may vary from project

to project, but is ideally considered to approach a ratio of

1:1. In our project we currently have a 2:3 ratio, although

others have reported a lower ratio1

. One of the corner

stones of XP is that having many tests available helps the

developers to overcome their fear for change: the tests will

provide immediate feedback if the system gets broken at a

critical place. The downside of having many tests, how-

ever, is that changes in functionality will typically involve

changes in the test code as well. The more test code we get,

the more important it becomes that this test code is as eas-

ily modifiable as the production code.

The key XP practice to keep code flexible is “refactor mer-

cilessly”: transforming the code in order to bring it in the

simplest possible state. To support this, a catalog of “code

smells” and a wide range of refactorings is available, vary-

ing from simple modifications up to ways to introduce de-

sign patterns systematically in existing code [5].

When trying to apply refactorings to the test code of our

project we discovered that refactoring test code is different

from refactoring production code. Test code has a distinct

set of smells, dealing with the ways in which test cases are

organized, how they are implemented, and how they inter-

act with each other. Moreover, improving test code in-

volves a mixture of refactorings from [5] specialized to test

code improvements, as well as a set of additional refactor-

ings, involving the modification of test classes, ways of

grouping test cases, and so on.

The goal of this paper is to share our experience in im-

proving our test code with other XP practitioners. To that

end, we describe a set of test smells indicating trouble in

test code, and a collection of test refactorings explaining

how to overcome some of these problems through a simple

program modification.

This paper assumes some familiarity with the xUnit frame-

work [3] and refactorings as described by Fowler [5]. We

will refer to refactorings described in this book using Name

1

This project started a year ago and involves the development of a prod-

uct called DocGen [4]. Development is done by a small team of five peo-

ple using XP techniques. Code is written in Java and we use the JUnit

Test smells

Does Refactoring of Test Smells

Induce Fixing Flaky Tests?

Fabio Palomba and Andy Zaidman

Delft University of Technology, The Netherlands

f.palomba@tudelft.nl, a.e.zaidman@tudelft.nl

Abstract—Regression testing is a core activity that allows devel-

opers to ensure that source code changes do not introduce bugs.

An important prerequisite then is that test cases are deterministic.

However, this is not always the case as some tests suffer from so-

called flakiness. Flaky tests have serious consequences, as they can

hide real bugs and increase software inspection costs. Existing

research has focused on understanding the root causes of test

flakiness and devising techniques to automatically fix flaky tests;

a key area of investigation being concurrency. In this paper,

we investigate the relationship between flaky tests and three

previously defined test smells, namely Resource Optimism, Indirect

Testing and Test Run War. We have set up a study involving 19,532

JUnit test methods belonging to 18 software systems. A key result

of our investigation is that 54% of tests that are flaky contain a

test code smell that can cause the flakiness. Moreover, we found

that refactoring the test smells not only removed the design flaws,

but also fixed all 54% of flaky tests causally co-occurring with

test smells.

Index Terms—Test Smells; Flaky Tests; Refactoring;

I. INTRODUCTION

Test cases form the first line of defense against the introduc-

tion of software faults, especially when testing for regression

faults [1], [2]. As such, with the help of testing frameworks

but just flaky [19]. Perhaps most importantly, from a psy-

chological point of view flaky tests can reduce a developer’s

confidence in the tests, possibly leading to ignoring actual test

failures [17]. Because of this, the research community has

spent considerably effort on trying to understand the causes

behind test flakiness [18], [20], [21], [22] and on devising

automated techniques able to fix flaky tests [23], [24], [25].

However, most of this research mainly focused the attention

on some specific causes possibly leading to the introduction of

flaky tests, such as concurrency [26], [25], [27] or test order

dependency [22] issues, thus proposing ad-hoc solutions that

cannot be used to fix flaky tests characterized by other root

causes. Indeed, according to the findings by Luo et al. [18]

who conducted an empirical study on the motivations behind

test code flakiness, the problems faced by previous research

only represent a part of whole story: a deeper analysis of

possible fixing strategies of other root causes (e.g., flakiness

due to wrong usage of external resources) is still missing.

In this paper, we aim at making a further step ahead toward

the comprehension of test flakiness, by investigating the role

of so-called test smells [28], [29], [30], i.e., poor design or

implementation choices applied by programmers during the

Empir Software Eng (2015) 20:1052–1094

DOI 10.1007/s10664-014-9313-0

Are test smells really harmful? An empirical study

Gabriele Bavota · Abdallah Qusef · Rocco Oliveto ·

Andrea De Lucia · Dave Binkley

Published online: 31 May 2014

© Springer Science+Business Media New York 2014

Abstract Bad code smells have been defined as indicators of potential problems in source

code. Techniques to identify and mitigate bad code smells have been proposed and stud-

ied. Recently bad test code smells (test smells for short) have been put forward as a kind

of bad code smell specific to tests such a unit tests. What has been missing is empirical

investigation into the prevalence and impact of bad test code smells. Two studies aimed at

providing this missing empirical data are presented. The first study finds that there is a high

diffusion of test smells in both open source and industrial software systems with 86 % of

JUnit tests exhibiting at least one test smell and six tests having six distinct test smells. The

second study provides evidence that test smells have a strong negative impact on program

comprehension and maintenance. Highlights from this second study include the finding that

comprehension is 30 % better in the absence of test smells.

On The Relation of Test Smells to

Software Code Quality

Davide Spadini,⇤‡ Fabio Palomba§ Andy Zaidman,⇤ Magiel Bruntink,‡ Alberto Bacchelli§

‡Software Improvement Group, ⇤Delft University of Technology, §University of Zurich

⇤{d.spadini, a.e.zaidman}@tudelft.nl, ‡m.bruntink@sig.eu, §{palomba, bacchelli}@ifi.uzh.ch

Abstract—Test smells are sub-optimal design choices in the

implementation of test code. As reported by recent studies, their

presence might not only negatively affect the comprehension of

test suites but can also lead to test cases being less effective

in finding bugs in production code. Although significant steps

toward understanding test smells, there is still a notable absence

of studies assessing their association with software quality.

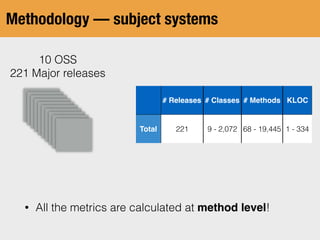

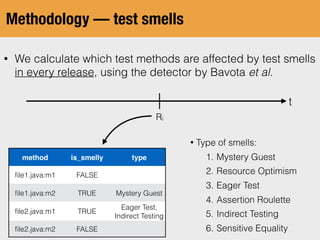

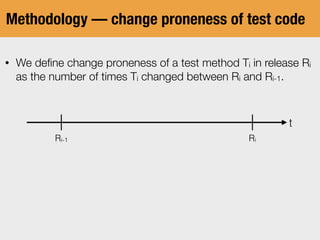

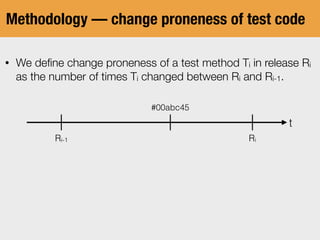

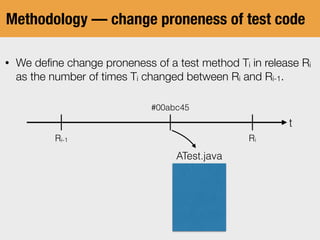

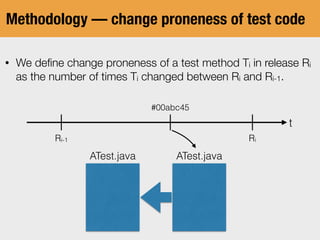

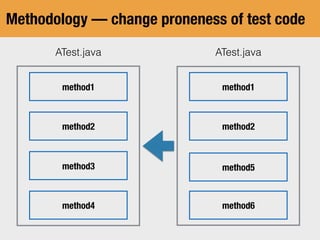

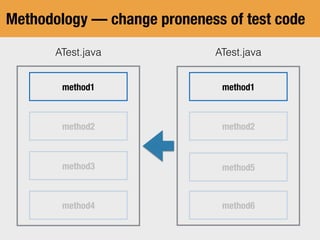

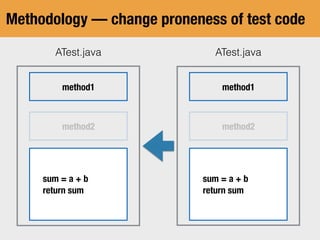

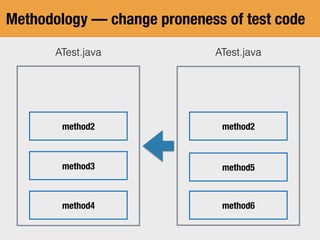

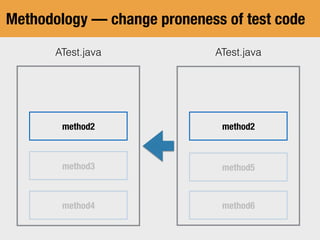

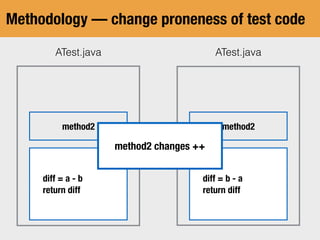

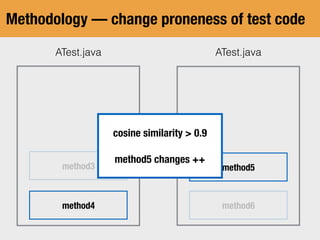

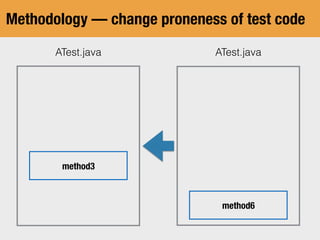

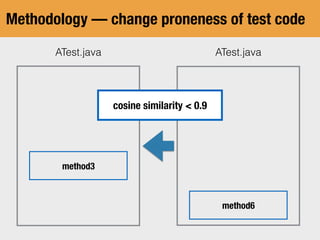

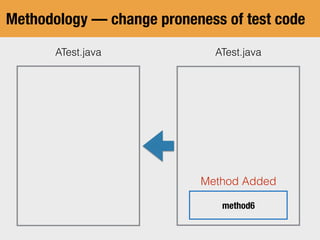

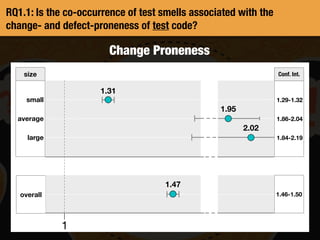

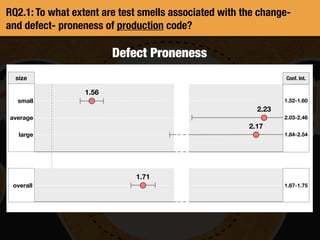

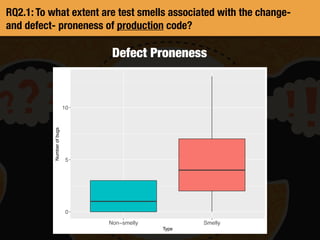

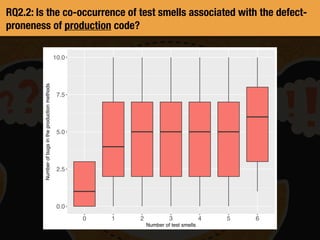

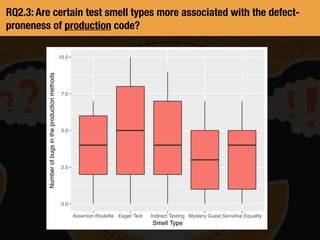

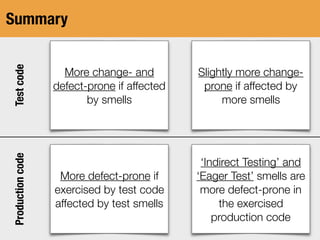

In this paper, we investigate the relationship between the

presence of test smells and the change- and defect-proneness of

test code, as well as the defect-proneness of the tested production

code. To this aim, we collect data on 221 releases of ten software

systems and we analyze more than a million test cases to investi-

gate the association of six test smells and their co-occurrence with

software quality. Key results of our study include:(i) tests with

smells are more change- and defect-prone, (ii) ‘Indirect Testing’,

‘Eager Test’, and ‘Assertion Roulette’ are the most significant

smells for change-proneness and, (iii) production code is more

defect-prone when tested by smelly tests.

I. INTRODUCTION

Automated testing (hereafter referred to as just testing)

has become an essential process for improving the quality of

software systems [12], [47]. In fact, testing can help to point

out defects and to ensure that production code is robust under

many usage conditions [12], [16]. Writing tests, however, is as

challenging as writing production code and developers should

maintain test code with the same care they use for production

found evidence of a negative impact of test smells on both

comprehensibility and maintainability of test code [7].

Although the study by Bavota et al. [7] made a first,

necessary step toward the understanding of maintainability

aspects of test smells, our empirical knowledge on whether

and how test smells are associated with software quality

aspects is still limited. Indeed, van Deursen et al. [74] based

their definition of test smells on their anecdotal experience,

without extensive evidence on whether and how such smells

are negatively associated with the overall system quality.

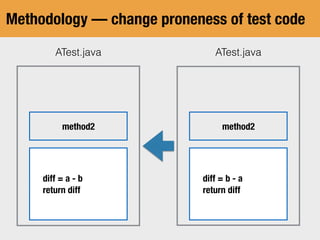

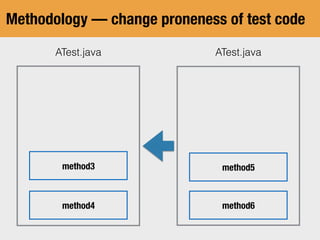

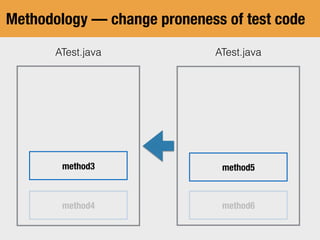

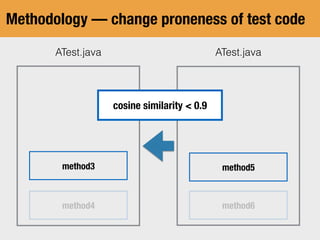

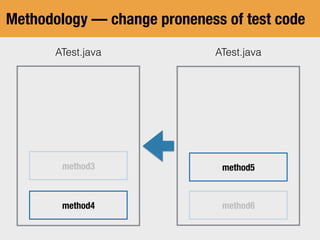

To fill this gap, in this paper we quantitatively investigate

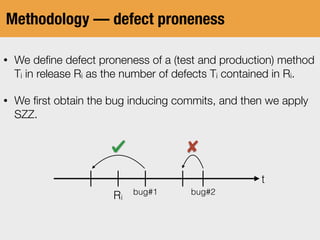

the relationship between the presence of smells in test methods

and the change- and defect-proneness of both these test

methods and the production code they intend to test. Similar

to several previous studies on software quality [24], [62], we

employ the proxy metrics change-proneness (i.e., number of

times a method changes between two releases) and defect-

proneness (i.e., number of defects the method had between two

releases). We conduct an extensive observational study [15],

collecting data from 221 releases of ten open source software

systems, analyze more than a million test cases, and inves-

tigate the association between six test smell types and the

aforementioned proxy metrics.

Based on the experience and reasoning reported by van](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/presentation-190527193051/85/On-The-Relation-of-Test-Smells-to-Software-Code-Quality-3-320.jpg)