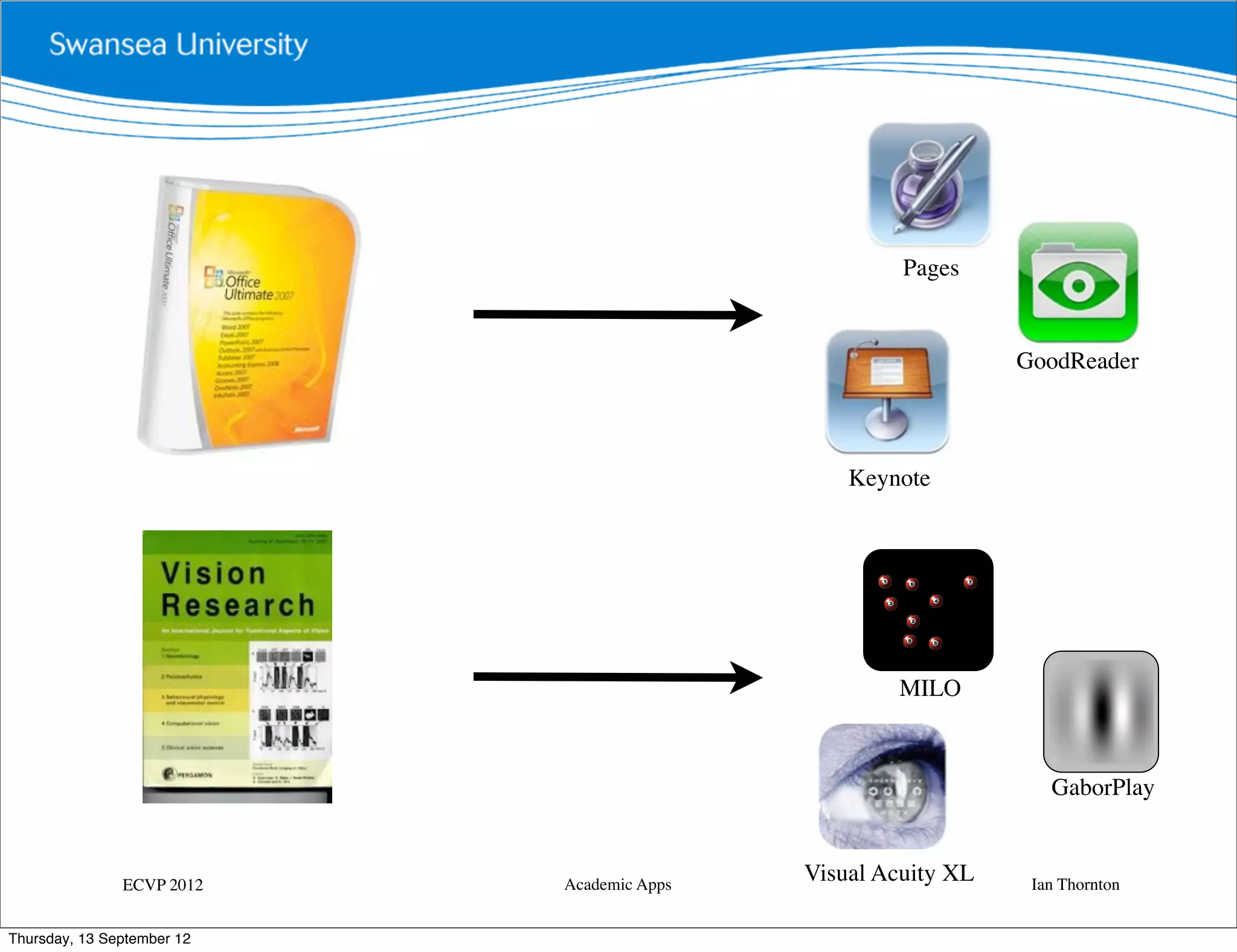

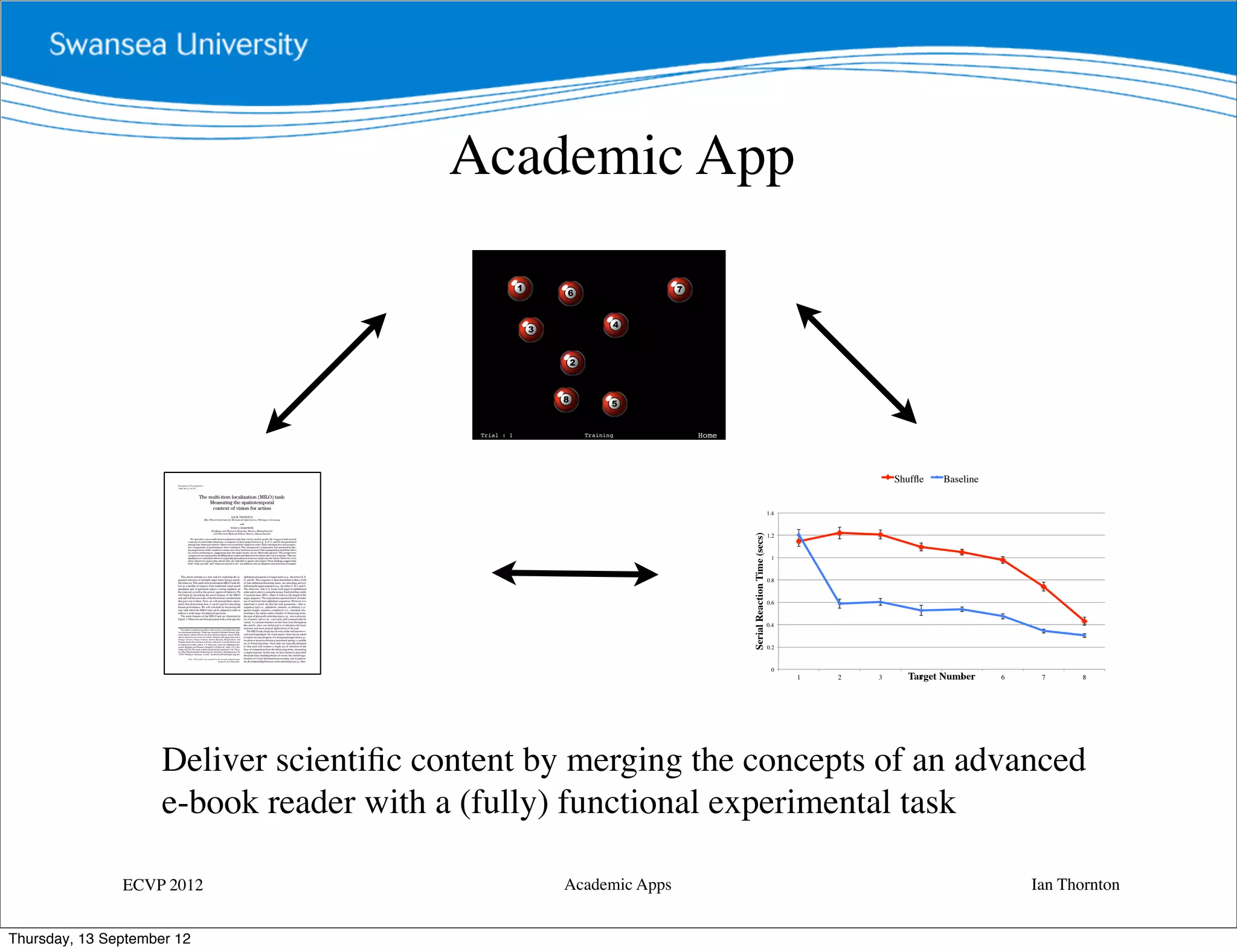

The document discusses the impact of mobile apps on producing and consuming scientific research, particularly through the lens of academic applications. It highlights the potential of mobile devices as experimental platforms and emphasizes the shift from traditional lab-based tasks to more flexible and interactive formats. Additionally, it touches on the evolution of apps and the implications for science communication and research methodologies.