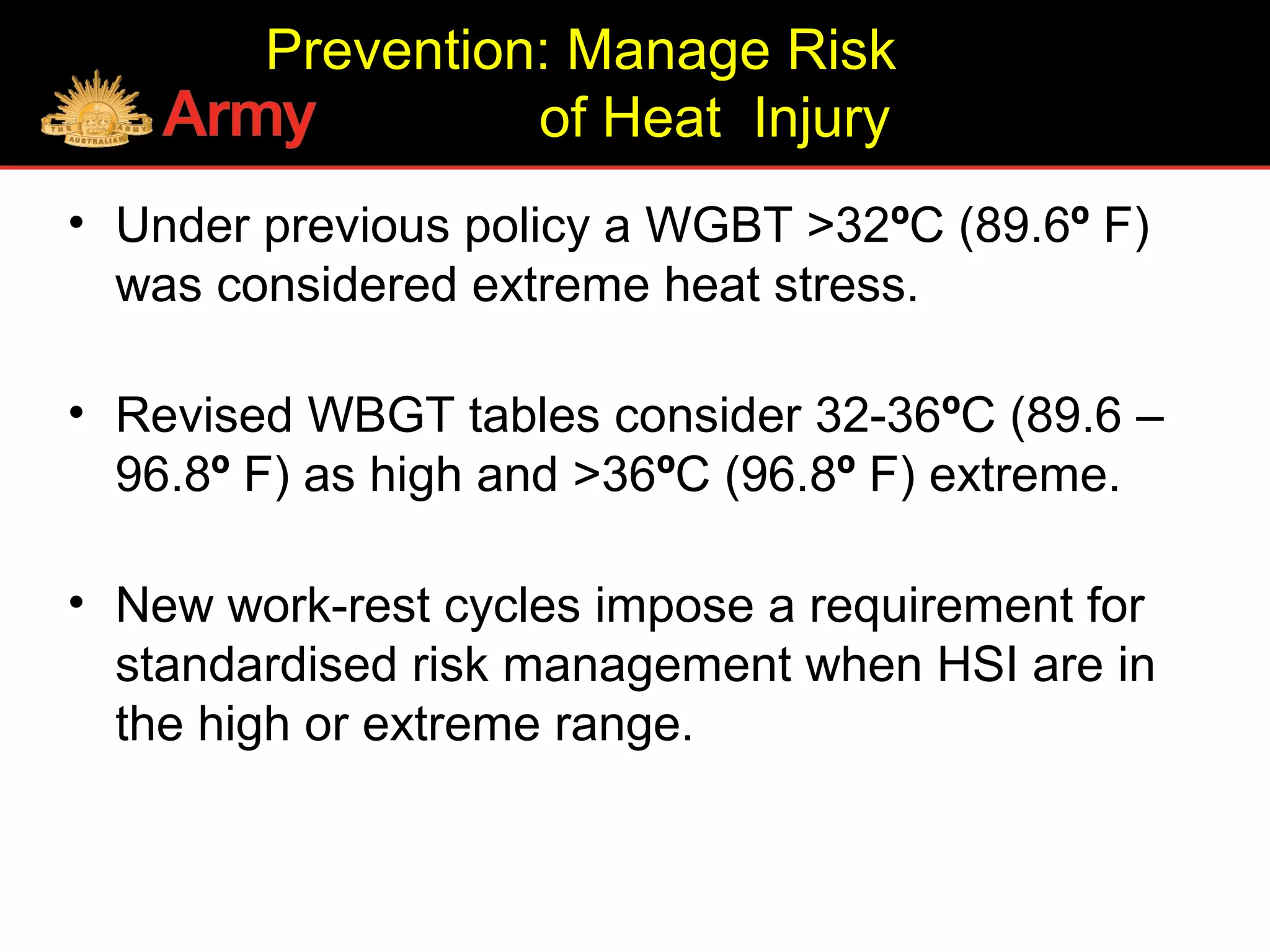

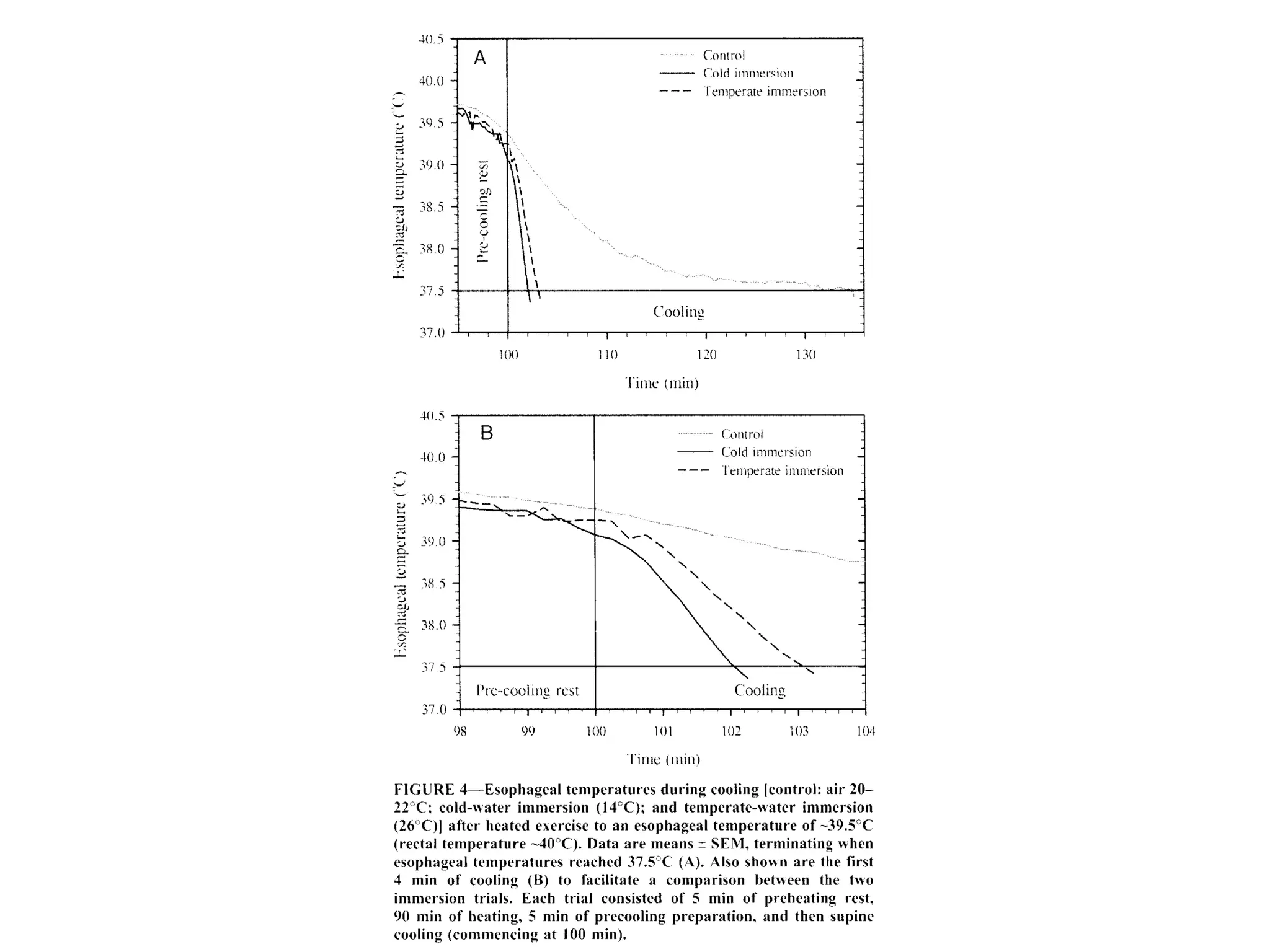

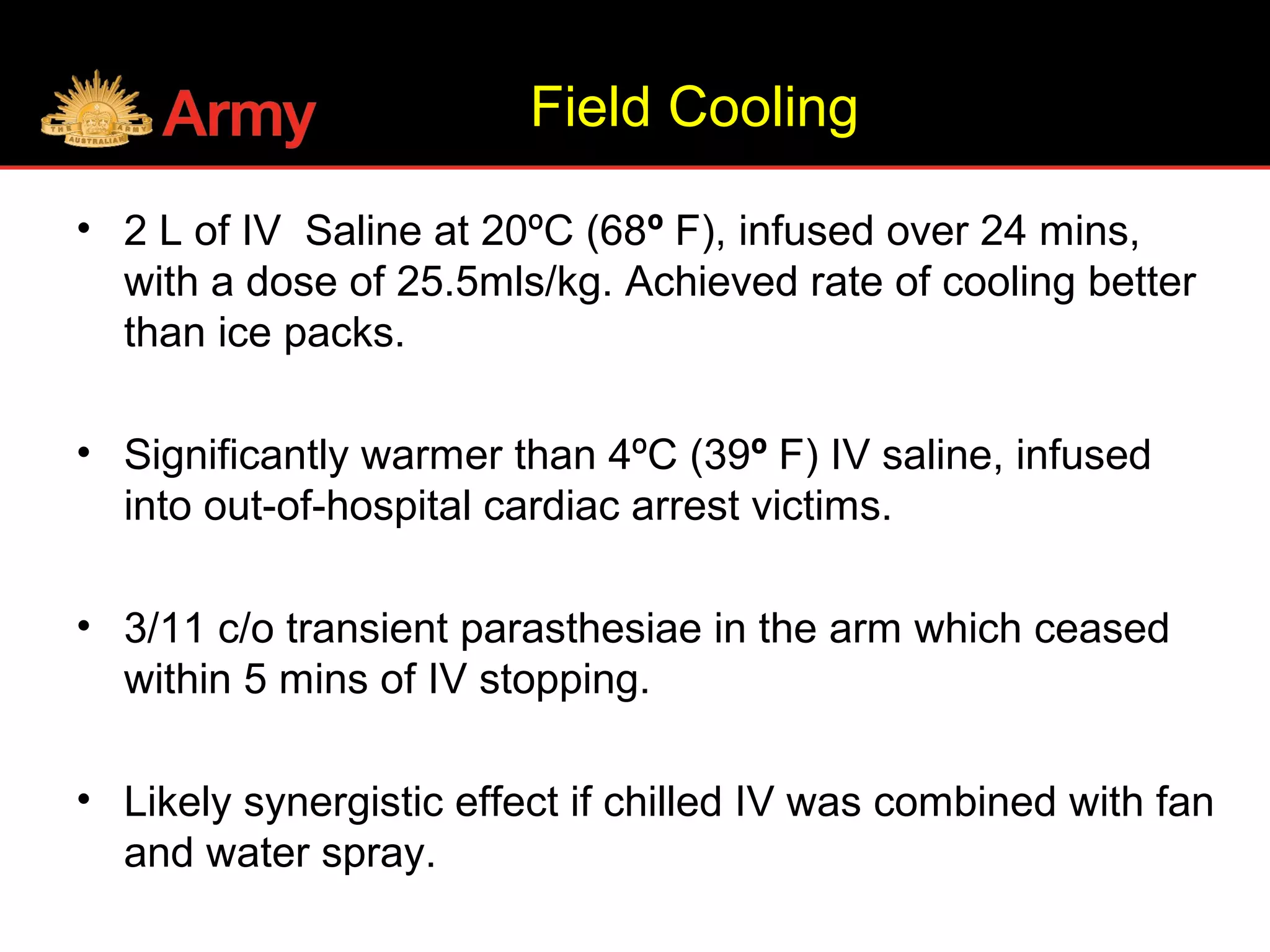

A soldier died of heatstroke during military training in the Northern Territory wet season. The early signs of heatstroke were not identified and ice packs were used to treat the soldier, which is an ineffective cooling method. The document identifies lessons around prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of heat injuries. It emphasizes that heatstroke is a medical emergency requiring rapid cooling through methods like cold water immersion or IV saline infusion, rather than slow methods like ice packs. The military has since improved heat injury education, policies, and management to prevent future deaths.

![Dehydration

• Humans are the only mammal to have salt in

their sweat.

• Thirst is driven by the concentration of

sodium [Na+

] in the plasma.

• Animals just lose water and increase their

plasma [Na+

] concentration. They then drink

to end their thirst, which occurs when their

[Na+

] concentration returns to normal.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ausheatstrokelessonslearnt-161108151058/75/Aus-heatstroke-lessons-learnt-10-2048.jpg)

![• Humans lose salt and water, so [Na+] can

change little, despite the loss of significant

fluid.

• The thirst reflex in humans does not kick in

until a person is 2-3% dehydrated.

• If you just drink WATER to thirst you will

always be around 2% dehydrated after

exercise.

Dehydration](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ausheatstrokelessonslearnt-161108151058/75/Aus-heatstroke-lessons-learnt-11-2048.jpg)

![• Extra water you drink will not stay in the

plasma unless consumed with sufficient

salt [Na+].

• If you wish to avoid dehydration after

activity

You MUST replace your salt losses.

Dehydration](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ausheatstrokelessonslearnt-161108151058/75/Aus-heatstroke-lessons-learnt-12-2048.jpg)