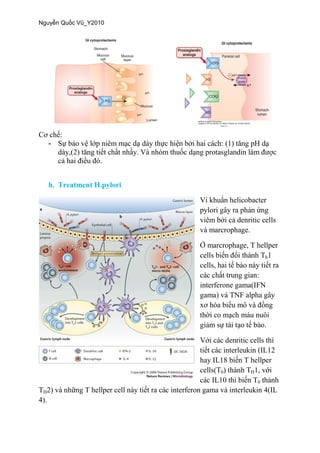

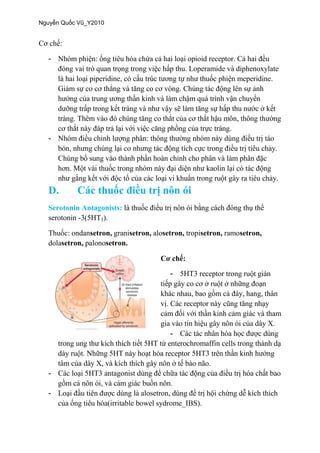

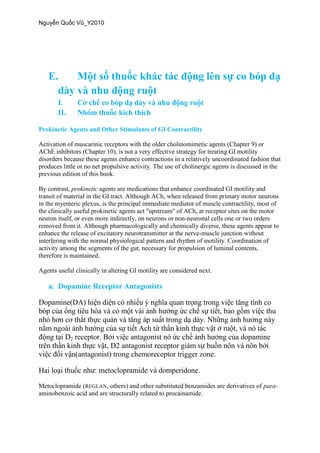

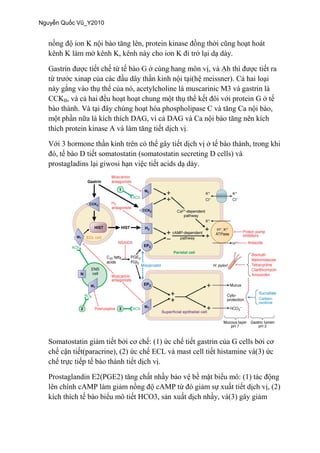

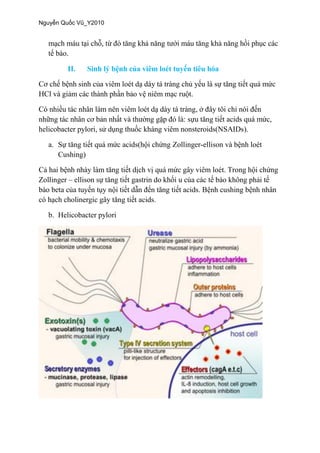

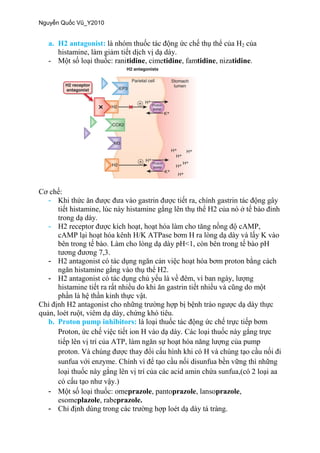

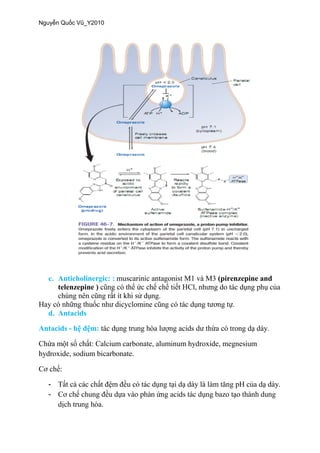

This document summarizes treatments for peptic ulcer disease and gastrointestinal motility disorders. It discusses several classes of drugs including H2 receptor antagonists, proton pump inhibitors, and prokinetic agents that work through different mechanisms such as dopamine receptor antagonism or serotonin receptor agonism. Specific drugs mentioned include metoclopramide, cisapride, domperidone, and prucalopride. It also covers treatments for conditions like Helicobacter pylori infection and discusses the roles of various hormones and neurotransmitters in gastrointestinal motility.

![-

-

e. Surcrafate

Sucralfate:

3

f. Colloidal bismuth: bismuth subsalicylate

-

-

-

H.pylori.

C

g. Prostaglandin: misoprostol (

prostaglandin E1 [PGE1])](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dclhchetieuha-170724085145/85/D-C-LY-H-C-H-TIEU-HOA-8-320.jpg)