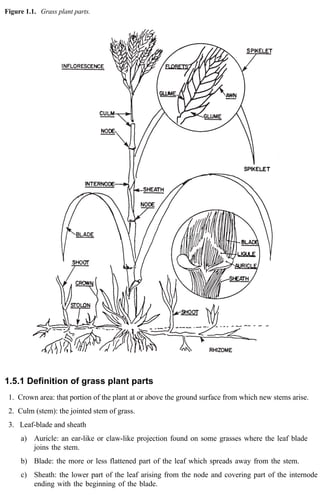

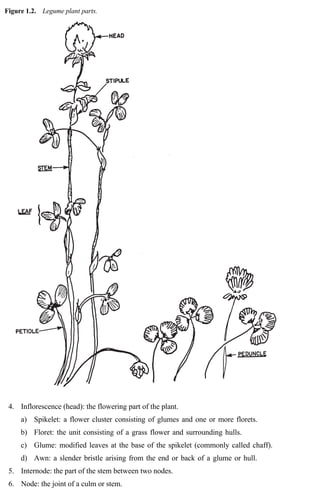

This document provides an overview of a training manual on forage seed production published by the International Livestock Centre for Africa (ILCA). The manual covers topics such as field multiplication, post-harvest conditioning, seed quality control, marketing, and economics. It describes four major systems of forage seed production in sub-Saharan Africa - opportunist labor intensive, opportunist mechanized, specialist labor intensive, and specialist mechanized. The first chapter focuses on field multiplication, including factors like site selection, matching forages to sites, crop establishment and management, and harvesting methods.