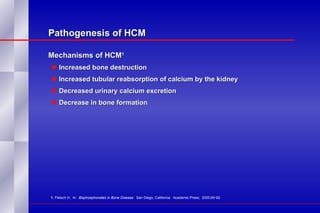

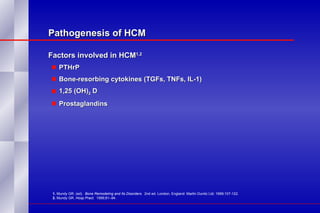

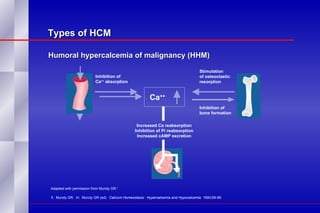

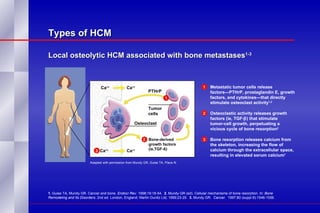

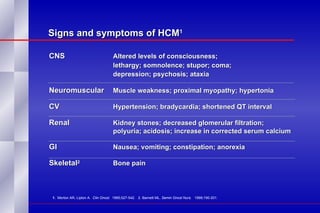

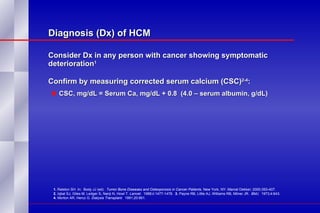

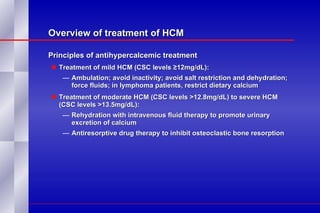

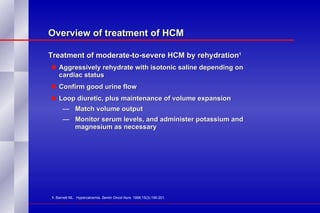

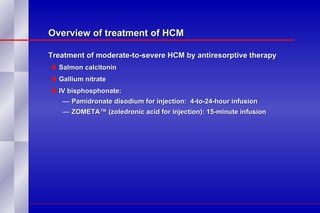

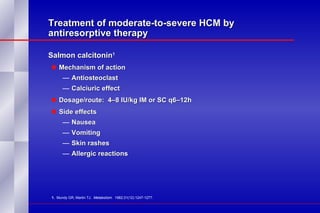

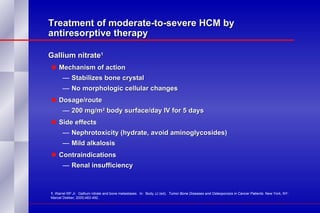

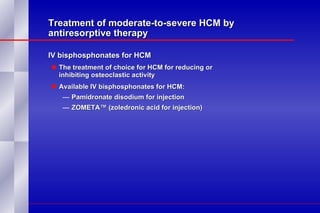

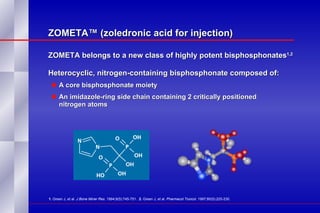

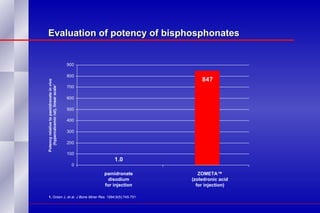

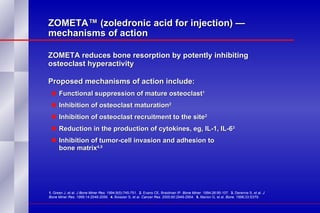

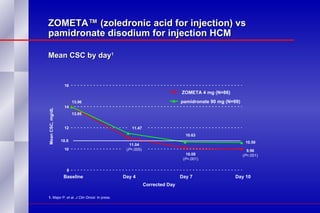

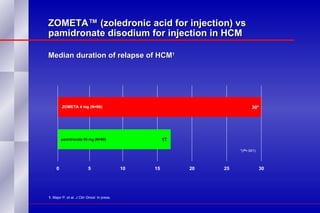

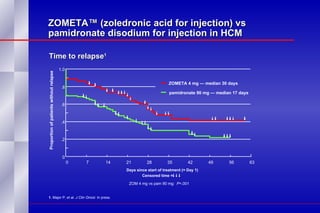

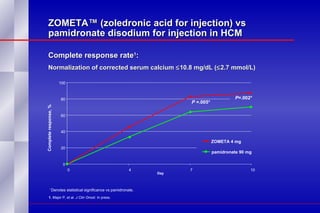

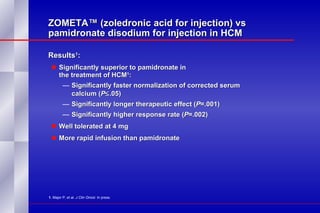

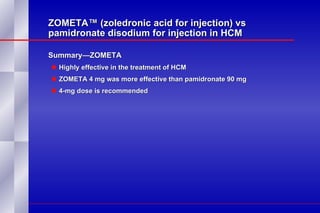

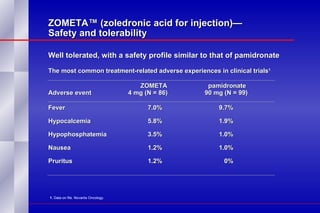

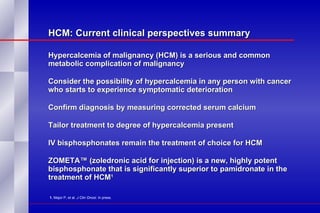

The document summarizes the pathogenesis and treatment of hypercalcemia of malignancy (HCM). It describes how HCM occurs via increased bone resorption from factors released by tumor cells like PTHrP, as well as the kidney's increased reabsorption of calcium. Signs and symptoms of HCM include fatigue, confusion and kidney problems. Treatment involves rehydration, bisphosphonates like zoledronic acid which strongly inhibits bone resorption, and calcitonin to reduce calcium levels. Zoledronic acid is the most potent bisphosphonate available and can reduce HCM within 24 hours.