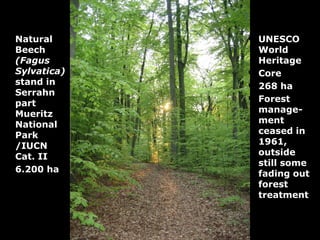

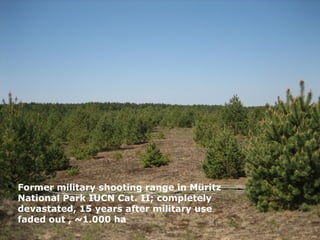

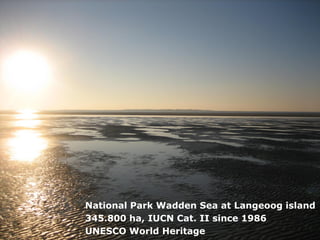

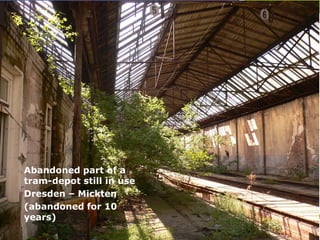

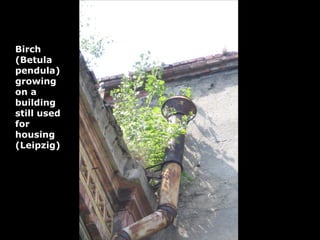

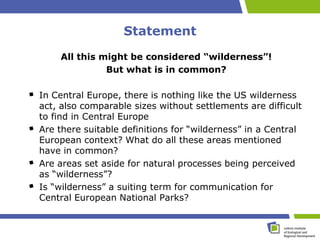

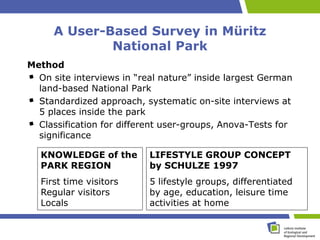

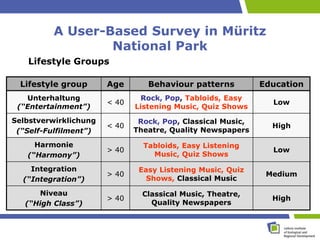

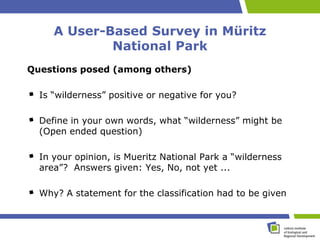

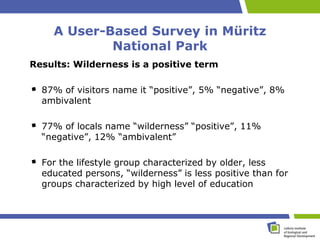

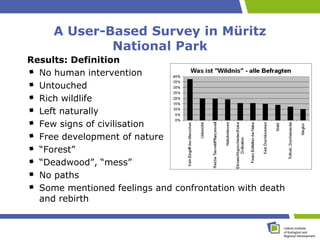

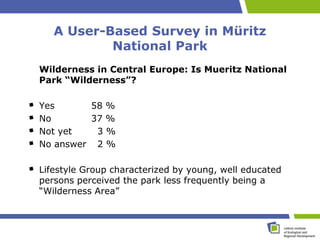

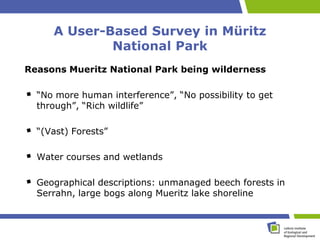

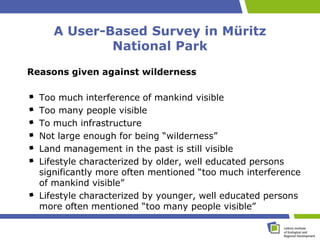

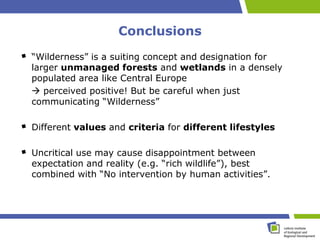

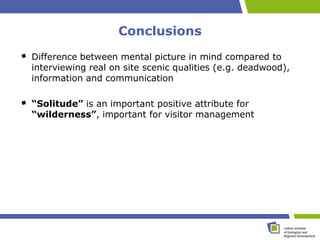

The document discusses the concept of "wilderness" in a Central European context. It provides examples of areas that could potentially be considered wilderness in Central Europe, such as long-unmanaged forests and former industrial sites. However, there is no universal definition of wilderness. The document also summarizes the results of a survey conducted in Mueritz National Park, Germany, which found that visitors generally have positive connotations with wilderness but definitions varied depending on lifestyle and education levels. While some saw the park as wilderness, others felt it showed too many signs of human impacts. The concept of wilderness may still be relevant for Central Europe if carefully defined and communicated.