The document discusses effective instructional practices for helping at-risk students achieve academic success, emphasizing that failure often results from schools' inability to meet diverse needs rather than student incapacity. It critiques common strategies like retention and pullout programs, highlighting their limited effectiveness, and recommends exploring prevention, classroom change, and remediation as more viable approaches. The authors conclude that tailored, early intervention strategies can significantly improve educational outcomes for at-risk students.

![risk of school failure (see p. 14, this

issue) We know we can do much

better with students at risk, that we can

begin to consider success in sch<x>] as

the birthright of virtually every child

While there is still more we must

learn, we know enough today to take

action. We can do no less for our most

vulnerable children.D

Authors' note Thi.s article was written

under funding from the Office of Educa

tional Research and Improvement. IS De

partment of Education (No OERI-G-86-

0006). However, any opinions expressed

are the authors and do not represent OERI

positions or policy

1 To get an idea of what effect size

means, consider that an effect si/e of -t-1 0

would indicate that a program increased

students scores by the equivalent of ap

proximately 100 points on the SAT Verbal

or Quantitative .scales, by two stanines, or

by 15 IQ points However, the effect sixes

given in the tables are only rough approx

imations (see Slavin et al 19H9)

"JDRP numbers refer to programs rec-

ogni/ed as effective by the U S Department

of Education s Joint Dissemination Review

Panel and listed in its publication. Educa

tional Programs That Work ( available

from Sopris West. 1120 Delaware Ave ,

Longmont. CO 80501)

References

Archambault. FX (1989) "Instructional

Setting and Other Design Features of

Compensatory Education Programs In

Effectiiv Programs for Students at Risk.

edited by R.E. Slavin, N I. Karweit, and

N.A. Madden Needham Heights. Mass.:

Allyn and Bacon

Becker, IIJ U98"1 ) The Impact of Com

puter Use on Learning What Research

Has Shou-n and What It Has Not ( Tech

Rep No 18). Baltimore. Md The Johns

Hopkins University Center for Research

on Elementary and Middle Schools

Berrueta-Clement, JR. LJ. Schweinhart,

W S Barnett. AS Epstem. and D P

Weikart (1984) Changed Liivs Ypsi-

lanti, Mich High/Scope

According to research, what are the most effective ways to help at-risk students?

~ i commonly used strategies flunking and pullout programs are ineffective at

;ing lasting achievement gains. The long-term effects of flunking on achieve-

e negative. Pullout programs, at best, do no more than kelp at-risk students

arty grades from falling further behind their peers.n> - means of preventing learning deficits, preschool and extended-day kinder

garten have not shown lasting effects on achievement. Disadvantaged children tend

i .. ;^ r,UKj language and IQ scores i "^'mMv after the experience, but

According to research, what are me niu*,_..~-... -Two commonly used strategies flunking and pullout programs are ineimuyc ...

producing lasting achievement gains. The long-term effects of flunking on achieve

ment are negative. Pullout programs, at best, do no more than kelp at-risk students

in the early grades from falling further behind their peers.As a means of preventing learning deficits, preschool and extended-day kinder

garten have not shown lasting effects on achievement. Disadvantaged children tend

to show improved language and IQ scores immediately after the experience, but

these effects wash out by the 2nd or 3rd grade. Preschool and extended-day

kindergarten may get students off to a good start in school, but these programs in

isolation are unlikely to reduce students' risk of school failure.

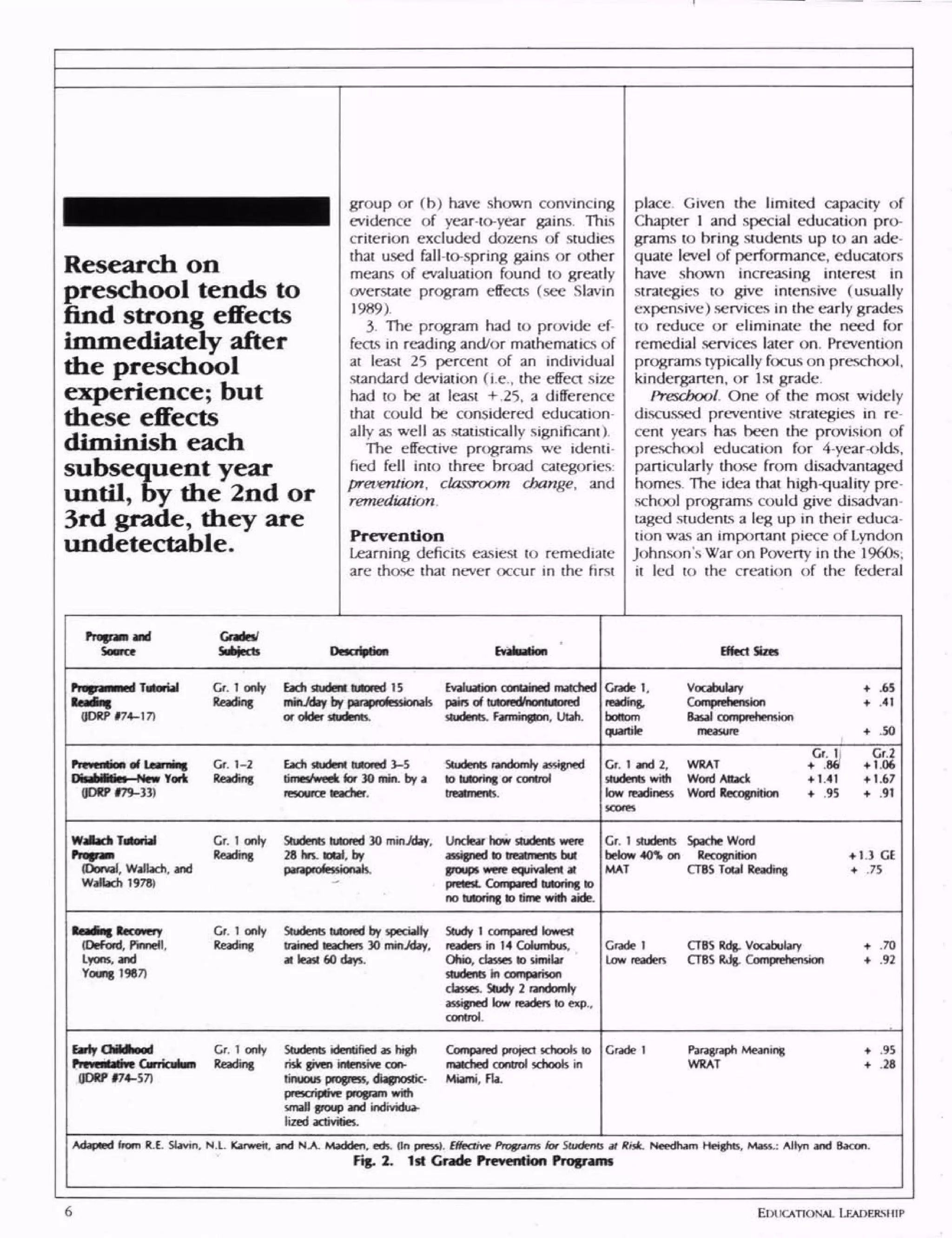

*" «*« does work for at-risk students?grade prevention programs that apply intensive resoi».e .s and/or small-group instruction, are extremely successful in increasing

students' reading achievement (fig. 2). Reading Recovery, the one model with data

on long-term effects, produced effects that persisted for at least two years.

~ ' ructional methods that accelerate student achiev- " ' oweciall

at risk, include continuous progress models (fig. 3

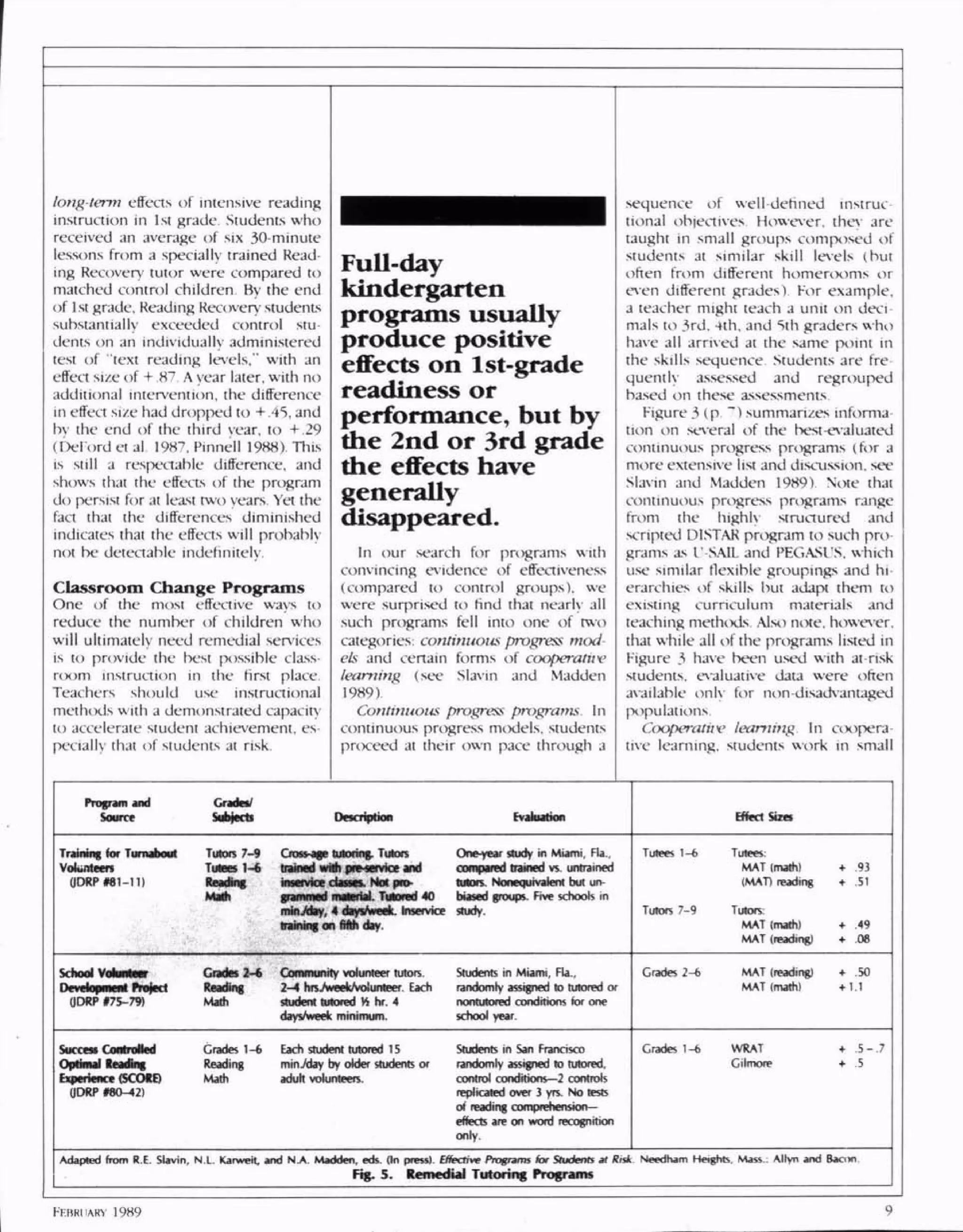

>pternentary/remedial programs that have proven effective include remedial

tutoring programs (fig. S) and some models of computer-assisted instruction (fig. 6).

' """Holes characterize effective programs for students at-risk:

...Jergarten nmy g^* ,solation are unlikely to reduce students' risk ot scnoui id,,-.-

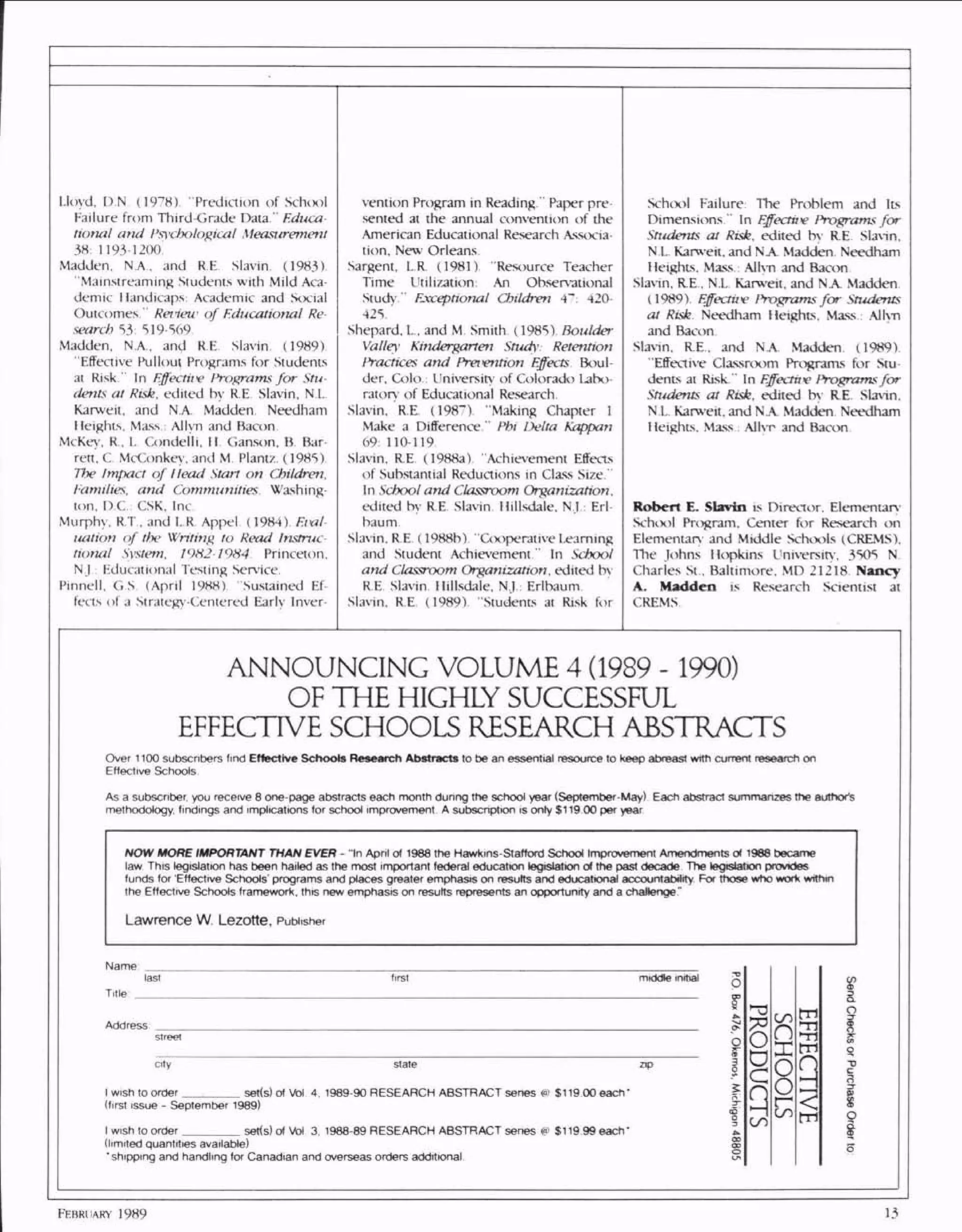

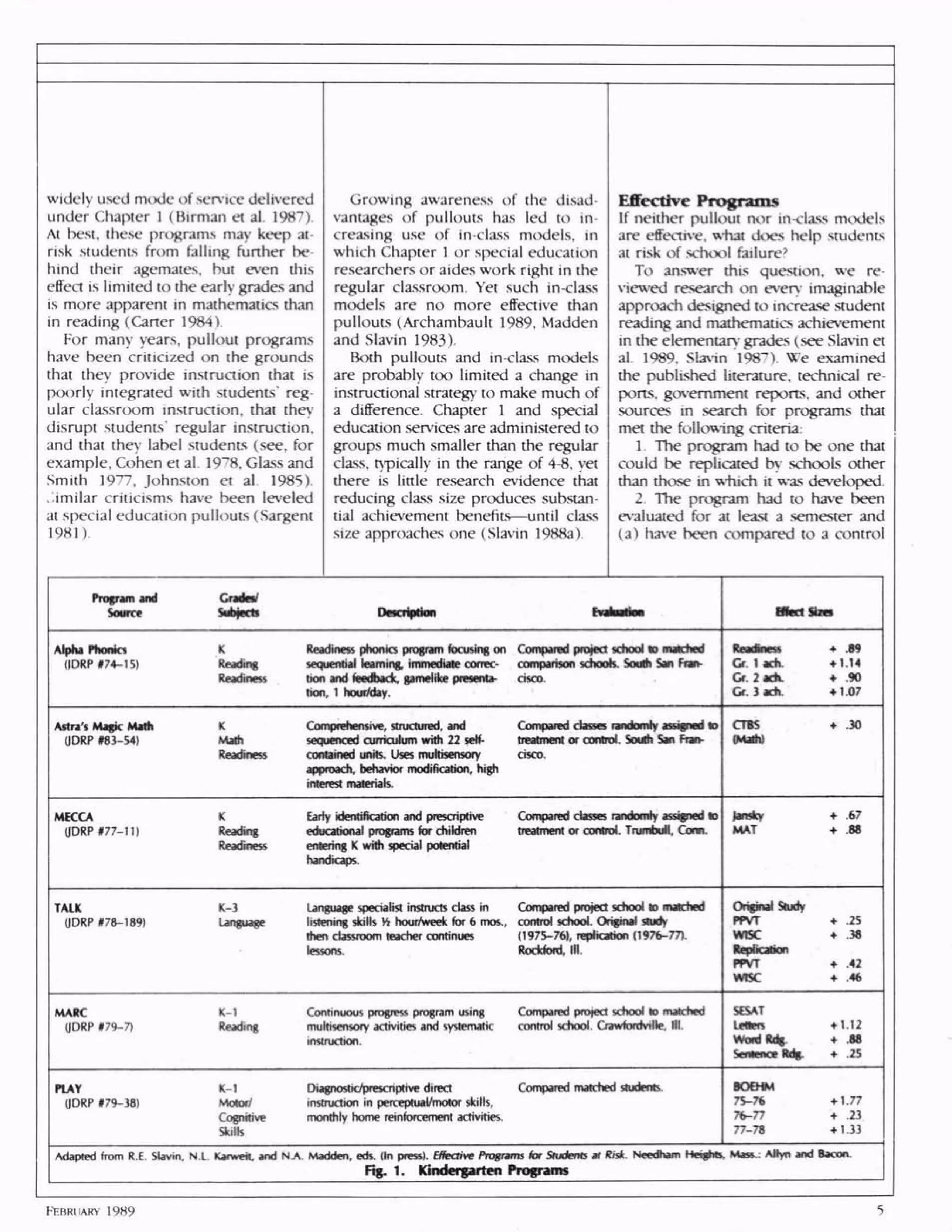

So what does work for at-risk students?~ First grade prevention programs that apply intensive resources, usually includ-

tutors and/or small-group instruction, are extremely successful in increasing

students' reading achievement (fig. 2). Reading Recovery, the one model with data

on long-term effects, produced effects that persisted for at least two years.

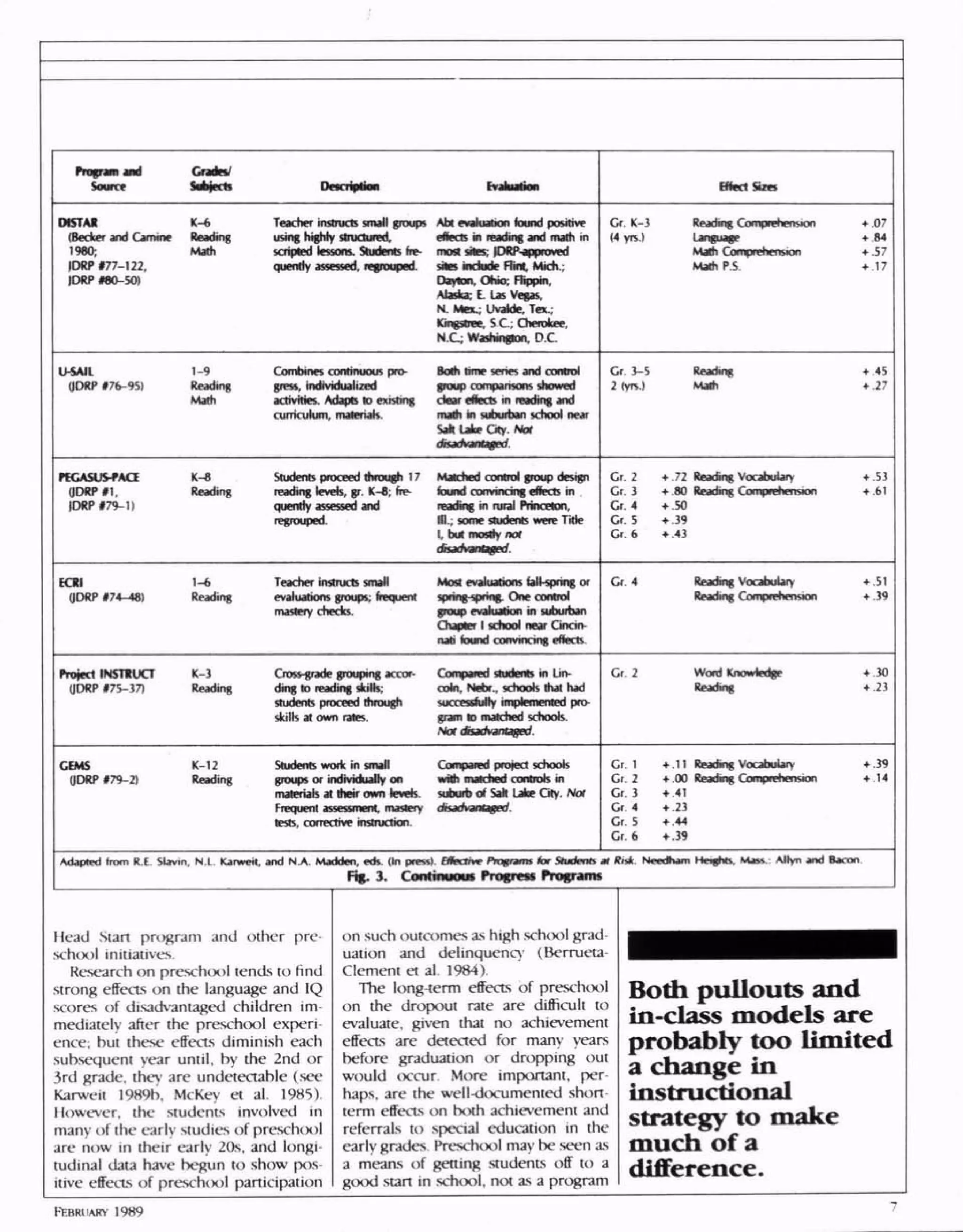

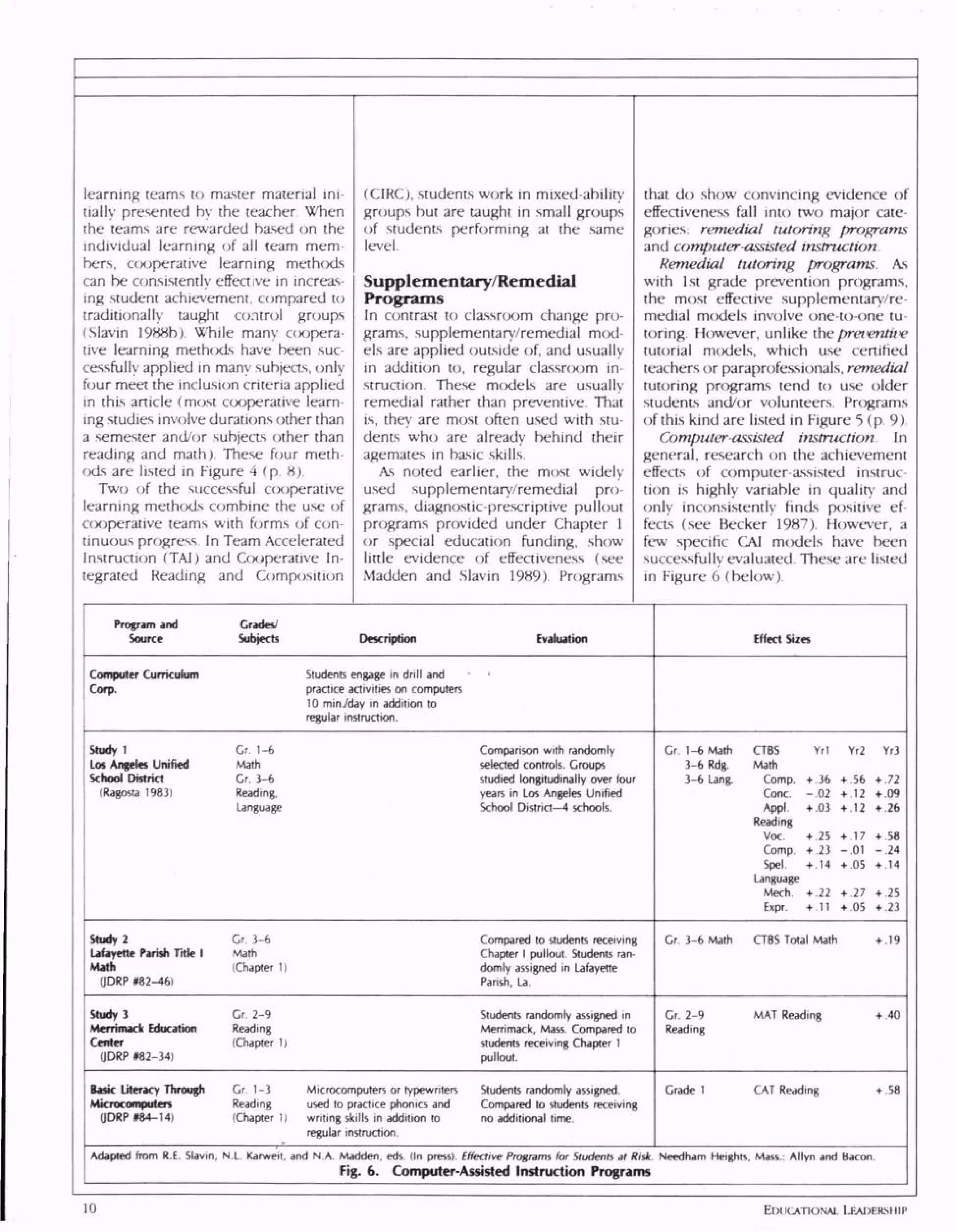

Instructional methods that accelerate student achievement, especially that of

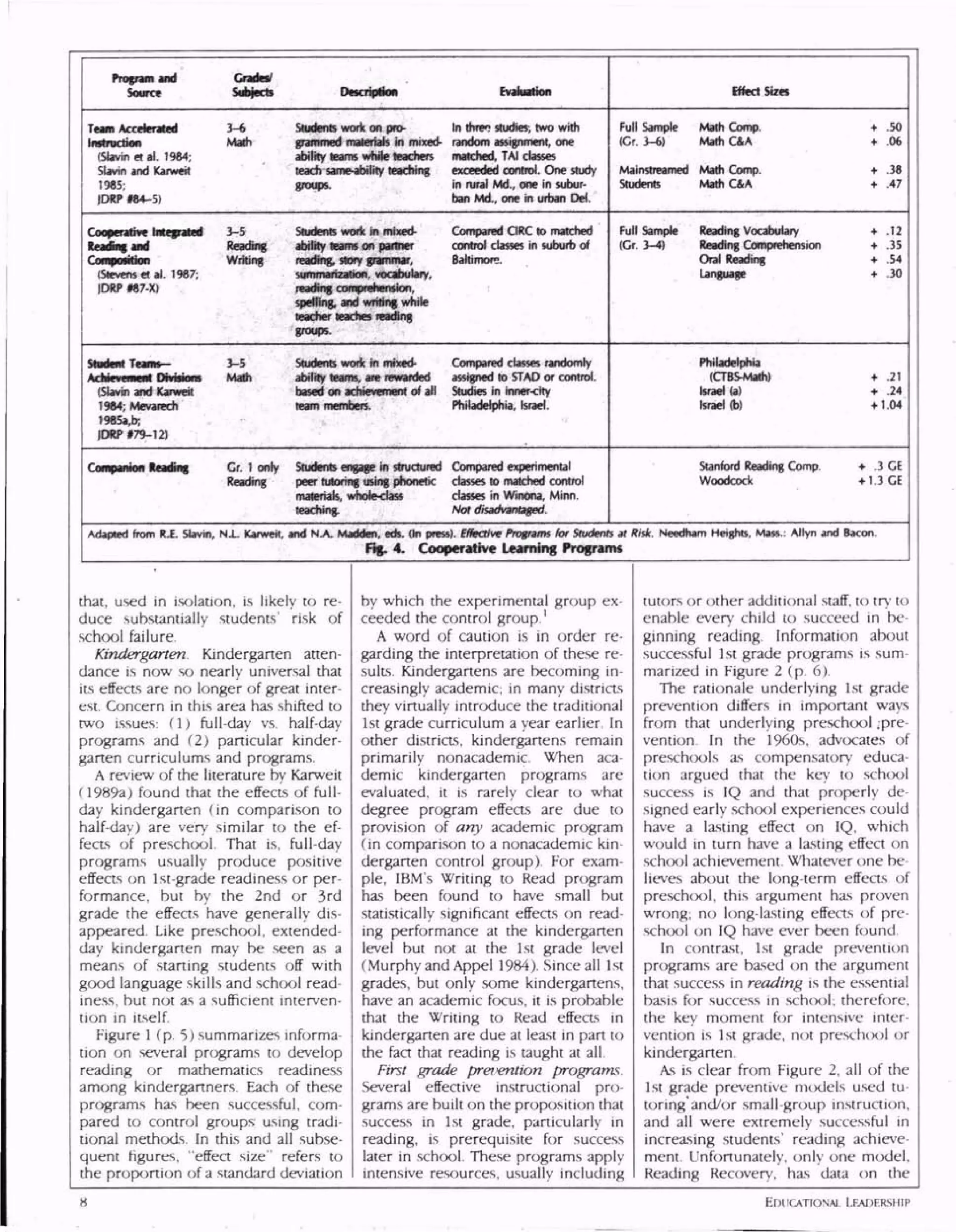

students at risk, include continuous progress models (fig. 3) and cooperative learning

programs (fig. 4)Supplementary/remedial programs that have proven effective include remedial

tutoring programs (fig. 5) and some models of computer-assisted instruction (fig. 6).

Some general principles characterize effective programs for students at-risk:

Effective programs are comprehensive and include teacher's manuals,

lum materials, lesson guides, and other supportive materials.Effective preventive and remedial programs are intensive, using one-to-one

tutoring or individually adapted computer-assisted instruction.

Effective programs frequently assess student progress and modify groupings or

instructional content to meet students' individual needs.

Birman, BF. ME Orland. RK lung. RJ

Anson. G.N Garcia, MT Moore, J.E

Kunkhouser. DR. Mornson. BJ Turn-

hull, and E.R. Reisner (198") The Cur

rent Operation of the Chapter / Pro

gram Washington. DC. Office of

Educational Research and Improvement,

U.S. Department of Education

Carter, I. F (198-1) "The Sustaining Effects

Study of Compensatory and Elementary

Education Educational Researcher H,

"4-13

Cohen, E , J Intilli, and S. Rohbtns (19~"H)

Teachers and Reading Specialists

C<x)oeration or Isolation:1 Reading

Teacher 32 281 28"

DeFord, DE. G.S. Pinnell, C.A I.vons. and

P Young (198") Ohio's Reading Recor

er Program Volume Vtf. Report of the

Eolloii'-l jp Studies Columbus Ohio

State University

Glass, G V , and M I, Smith (19"~> Pullout

in Compensatory Fducation Washing

ton, DC IS Department of Health,

Education, and Welfare

Gottfredson, G.D (April 1988) "You Get

What You Measure You Get What You

Don't. Higher Standards, Higher Test

Scores, More Retention in Grade Paper

presented at the annual convention of

the American Educational Research As

sociation, New Orleans

Howard. MAD . and RJ Anderson (19~8)

Early Identification of Potential School

Dropouts A Literature Review Child

Welfare 52: 221 231

Jackson, GB (I9"5) The Research Evi

dence on the Effects of Grade Reten

lion " Rei'ieu' of Educational Research

45. 613-635

Johnston, P . R Allington, and P Afflerbach

(1985) "The Congruence of Classrcxim

and Remedial Instruction F.lementan

SchoolJournal 85 465-4"~

Karweit. N I. (I989a) "Effective Kindergar

ten Programs and Practices for Students

at Risk of Academic Failure " In Effectiiv

Programsfor Students at Risk, edited by

RE. Slavin. N I.. Karweit. and N.A Mad

den Needham Heights, Mass : Allyn and

Bacon

Karweit. N1. (1989h) "Preschool Pro

grams for Students at Risk of Sch<x>l

Failure In Effective Programs for Stu

dents at Risk, edited by R E Slavin, N I.

Karweii. and N.A. Madden Needham

Heights. Mass Allyn and Bacon

Kelly. FJ , DJ Veldman, and C McGuire

(1964) Multiple Discriminant Predic

lion of Delinquency' and Schtxjl Drop-

outs Educational and I'sychological

Measurement 24 535-544

12 EDUCATIONAL LEADERSHIP](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/what-works-for-students-at-risk-140612001530-phpapp01/75/What-works-for-students-at-risk-9-2048.jpg)