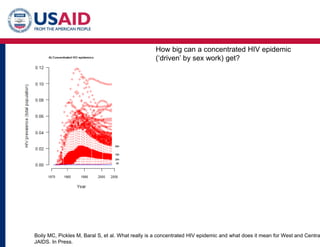

This document summarizes a panel discussion on sex workers and HIV. It discusses how targeted interventions for sex workers like condom distribution, STI treatment, and ART can help reduce HIV transmission. Studies show comprehensive sex worker programs that include these interventions along with structural support and community mobilization have led to significant reductions in HIV incidence of up to 70% in some places. The document outlines evidence that sex work can be a major driver of HIV epidemics in sub-Saharan Africa, with sex work responsible for 58-89% of infections in some modeling studies. It emphasizes that community-driven responses that give sex workers control over designing and implementing interventions have been shown to be most effective.