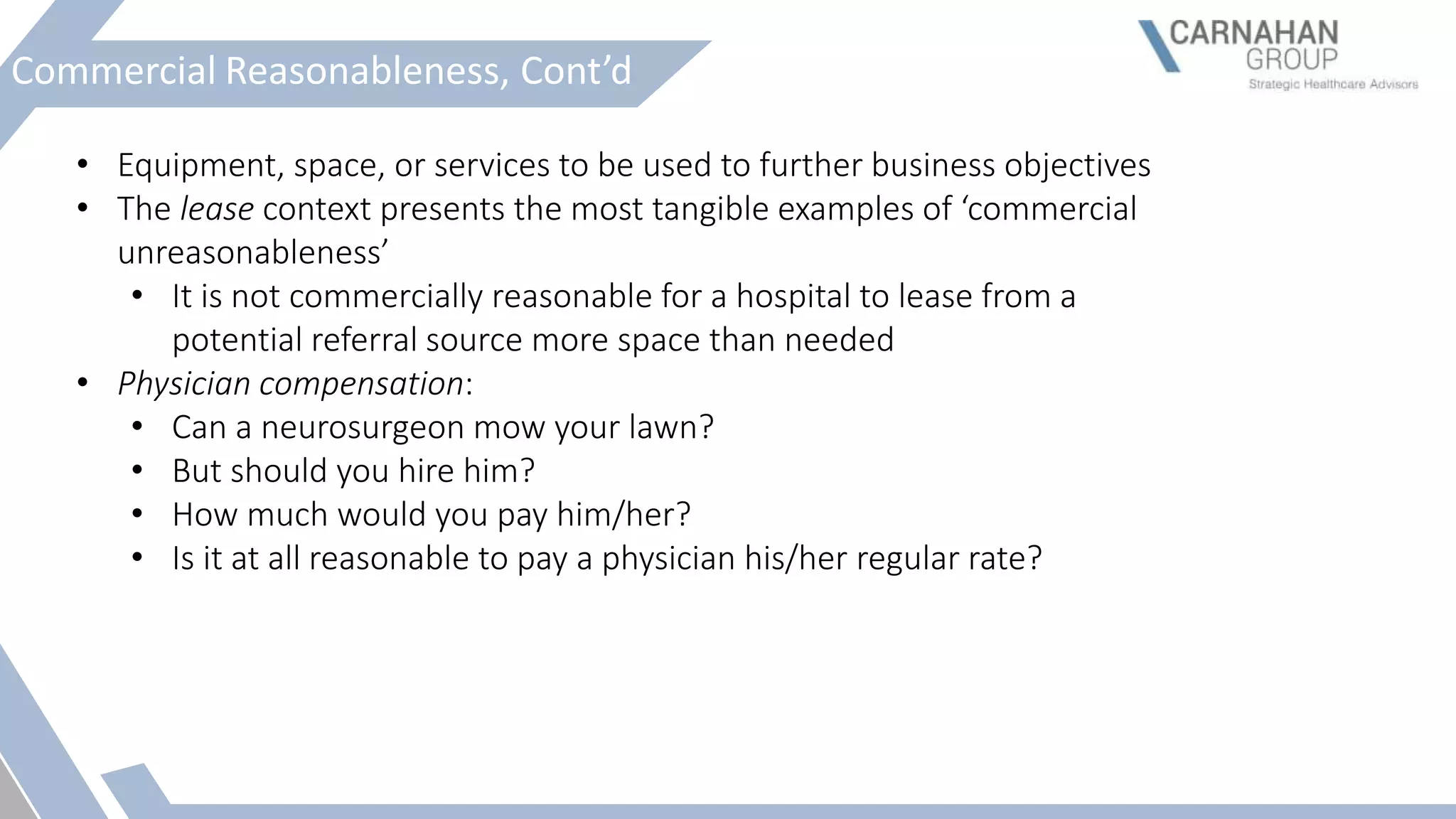

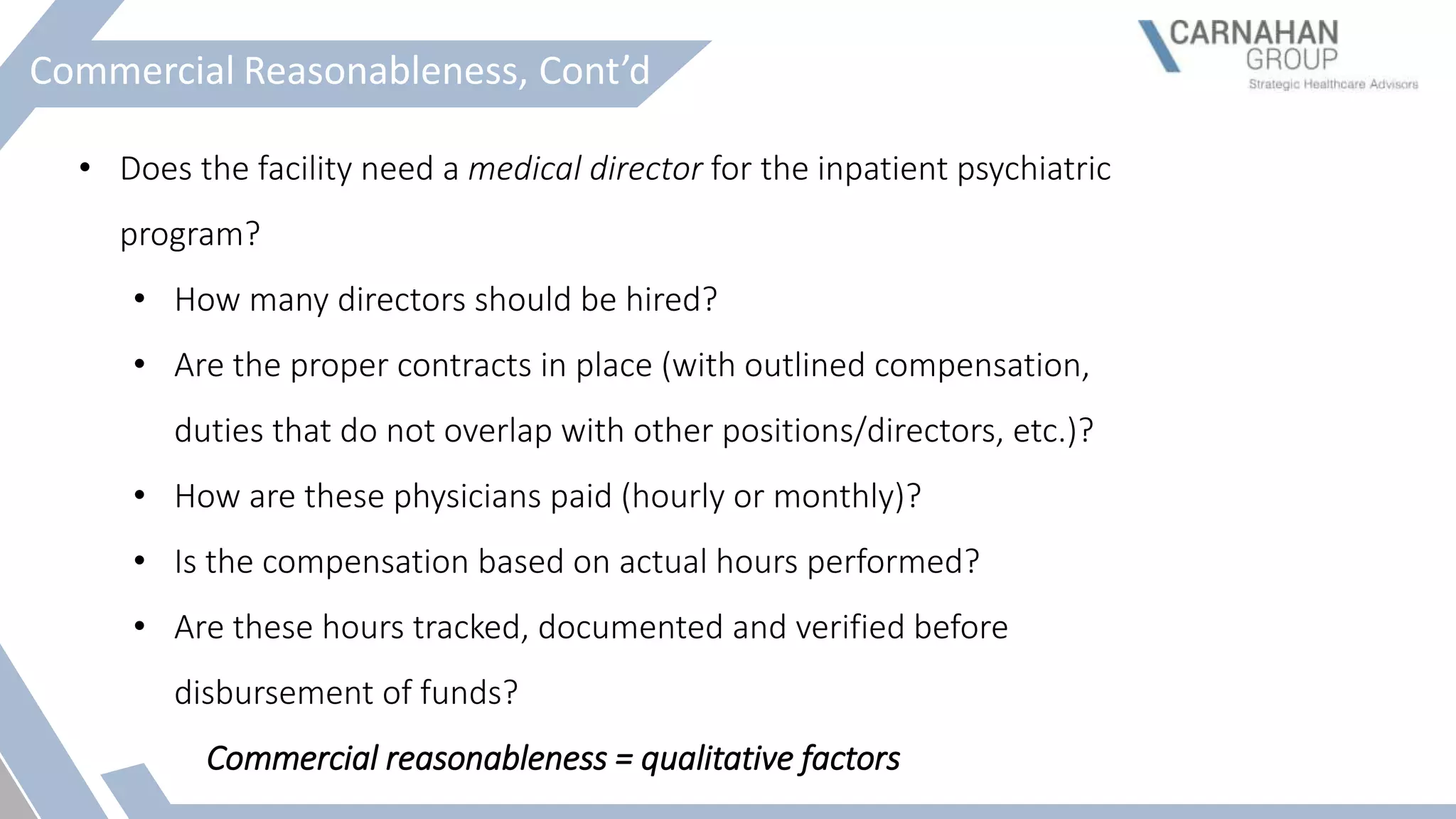

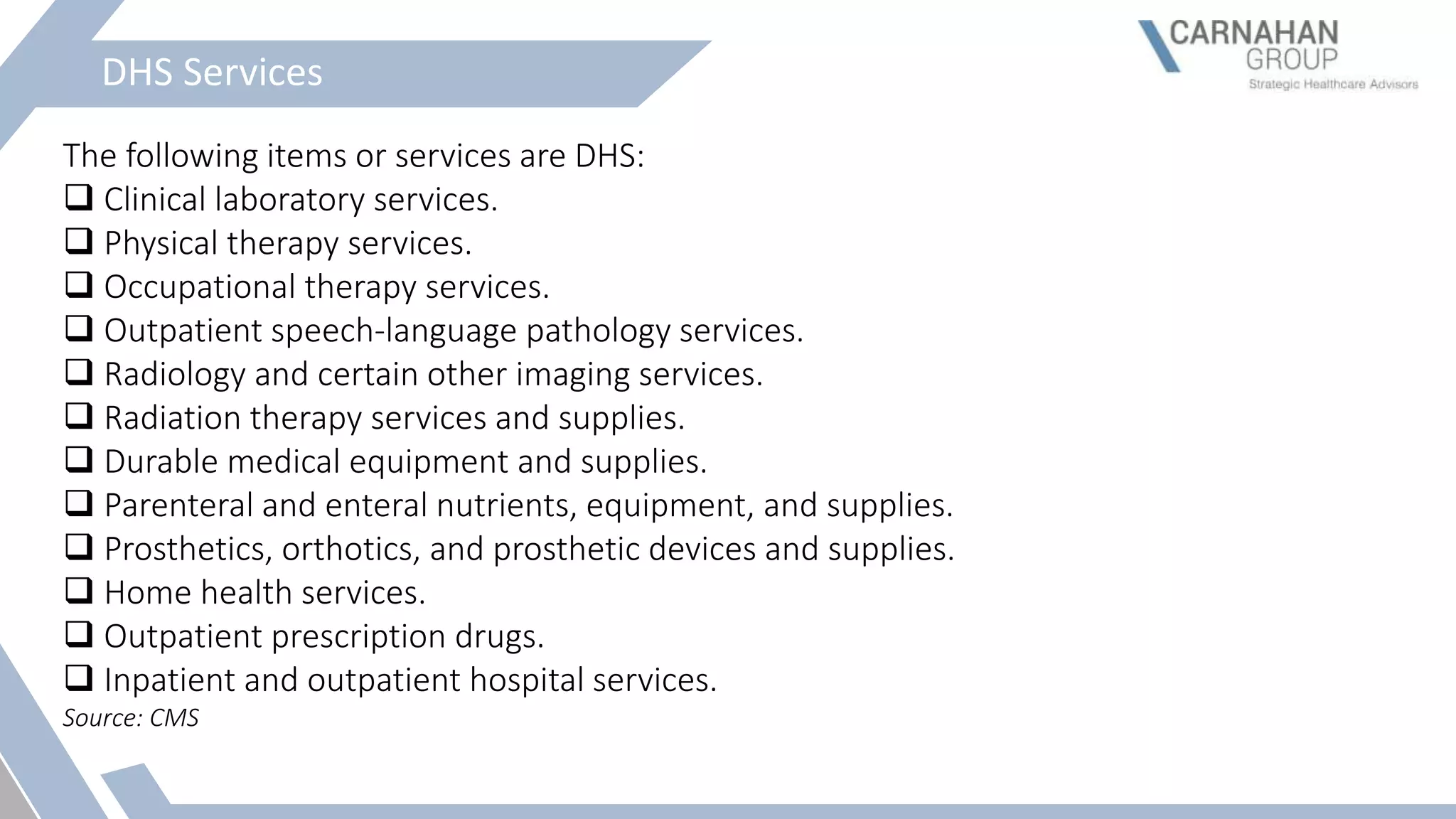

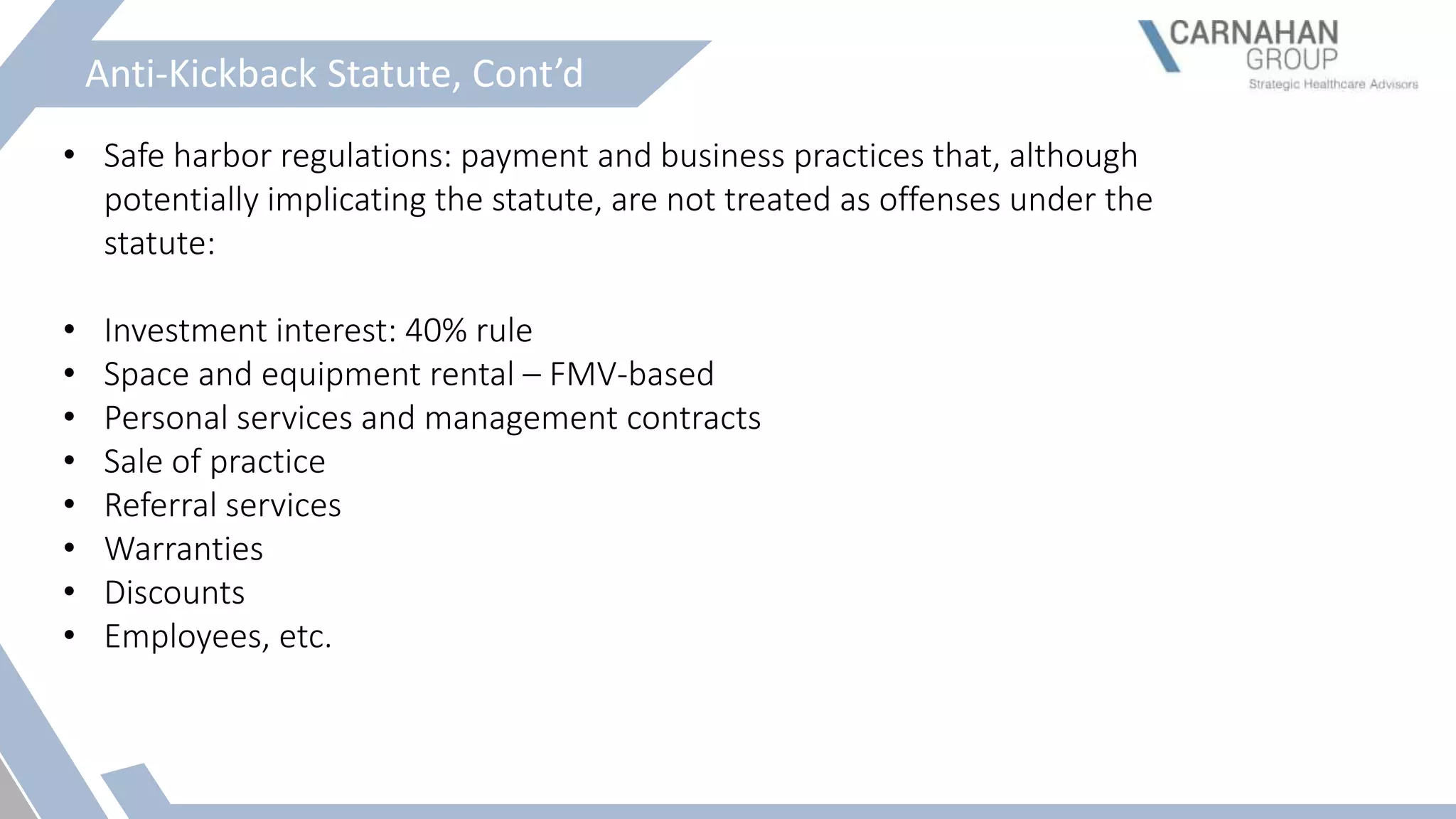

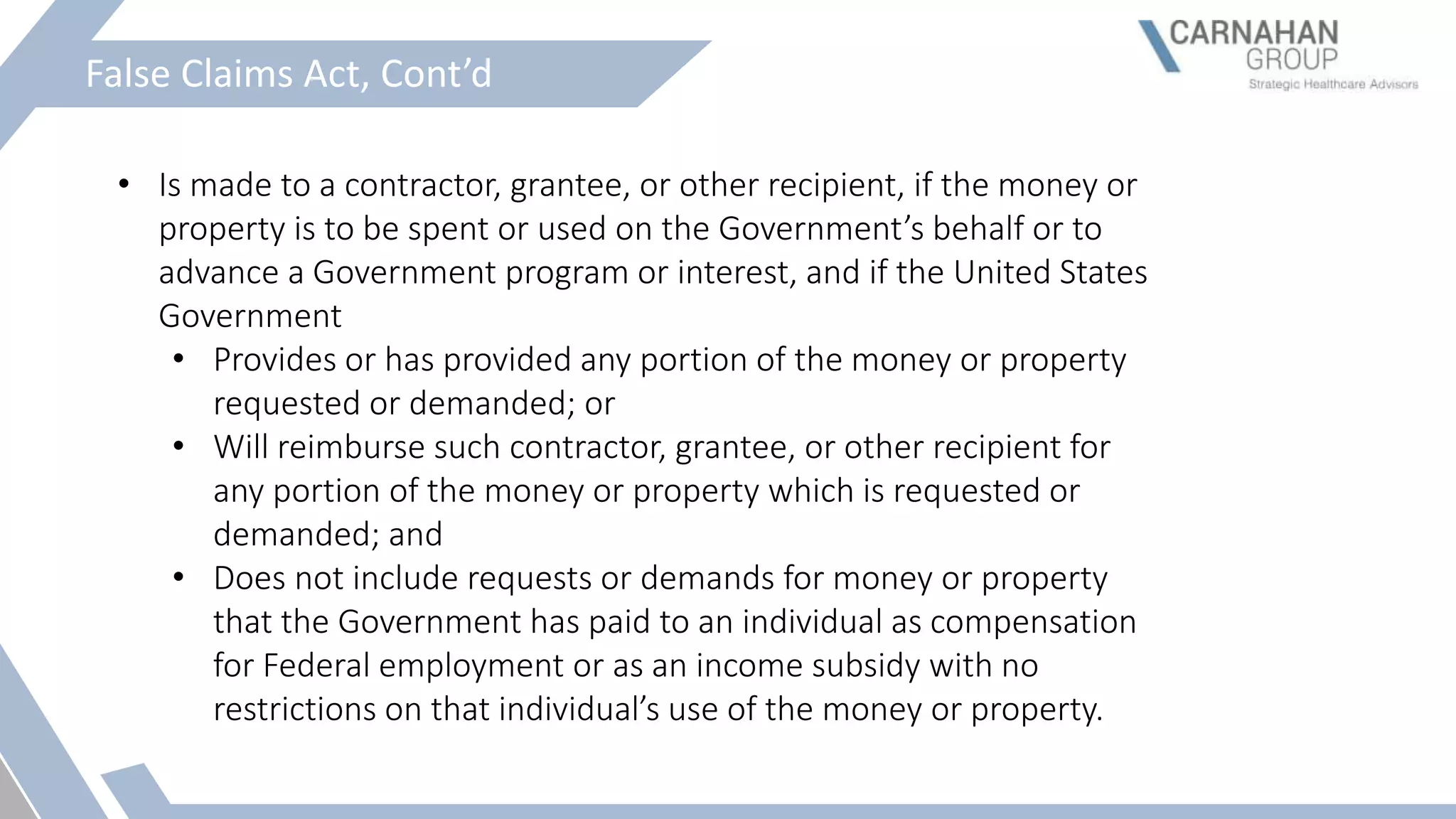

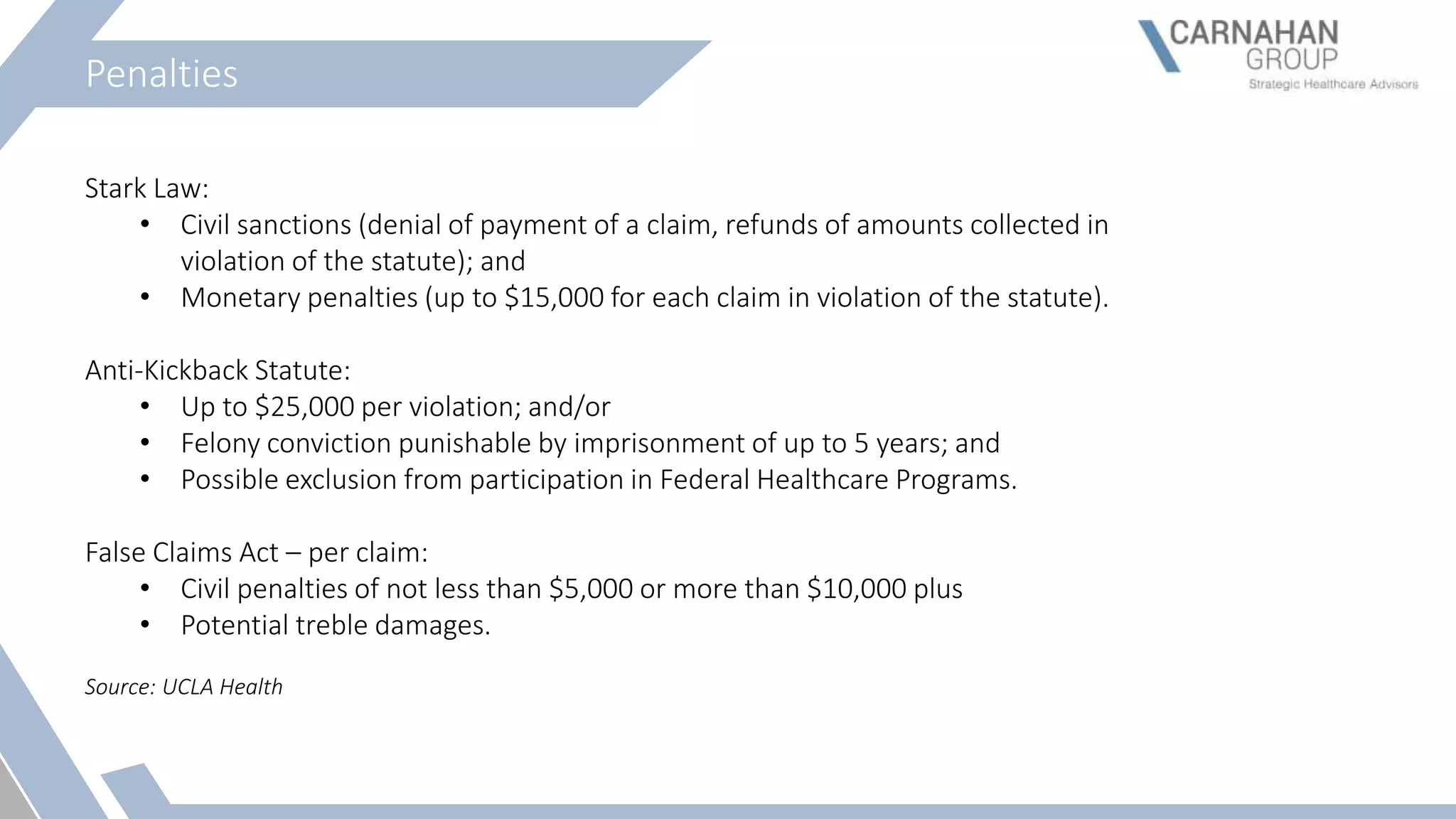

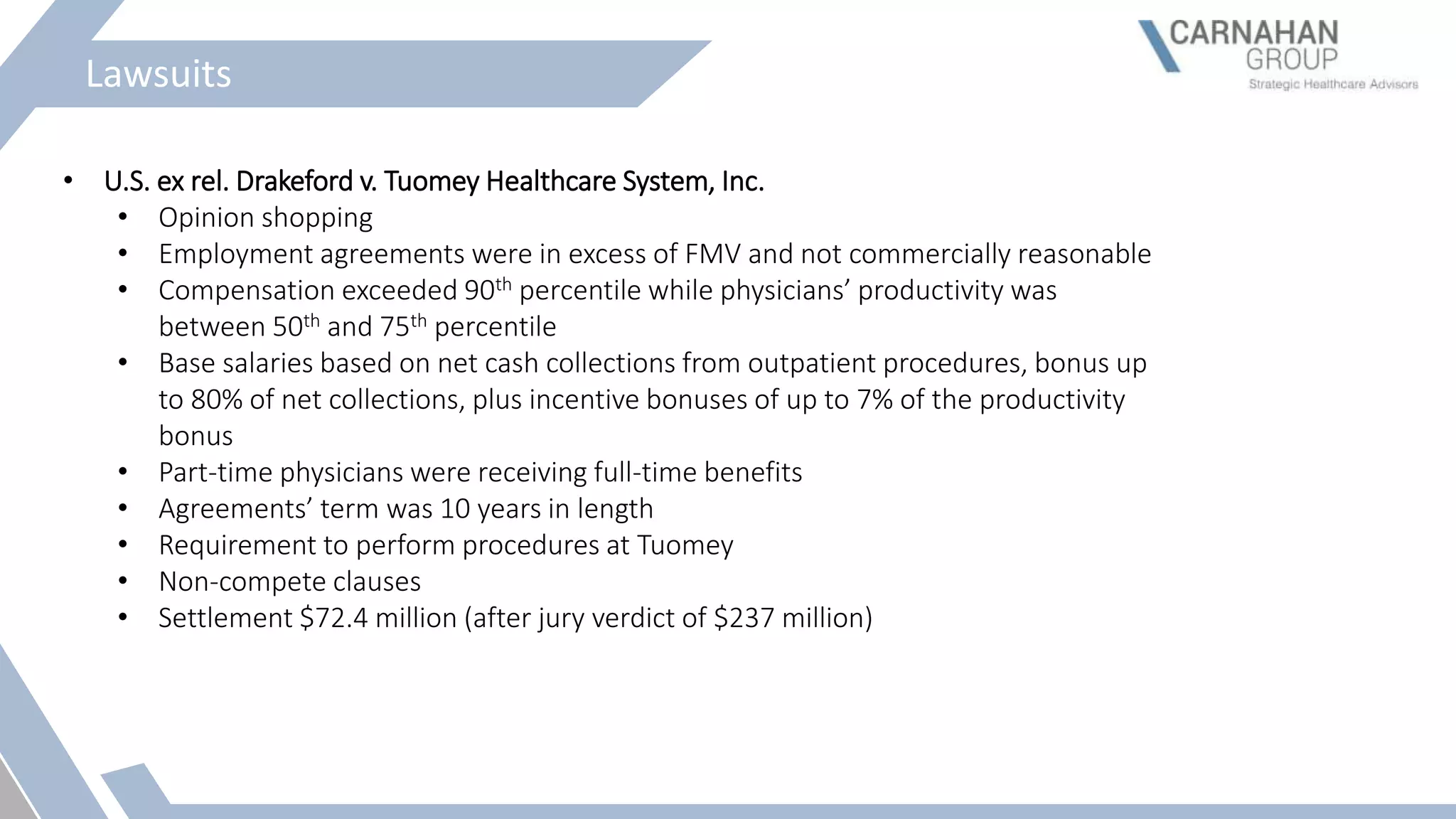

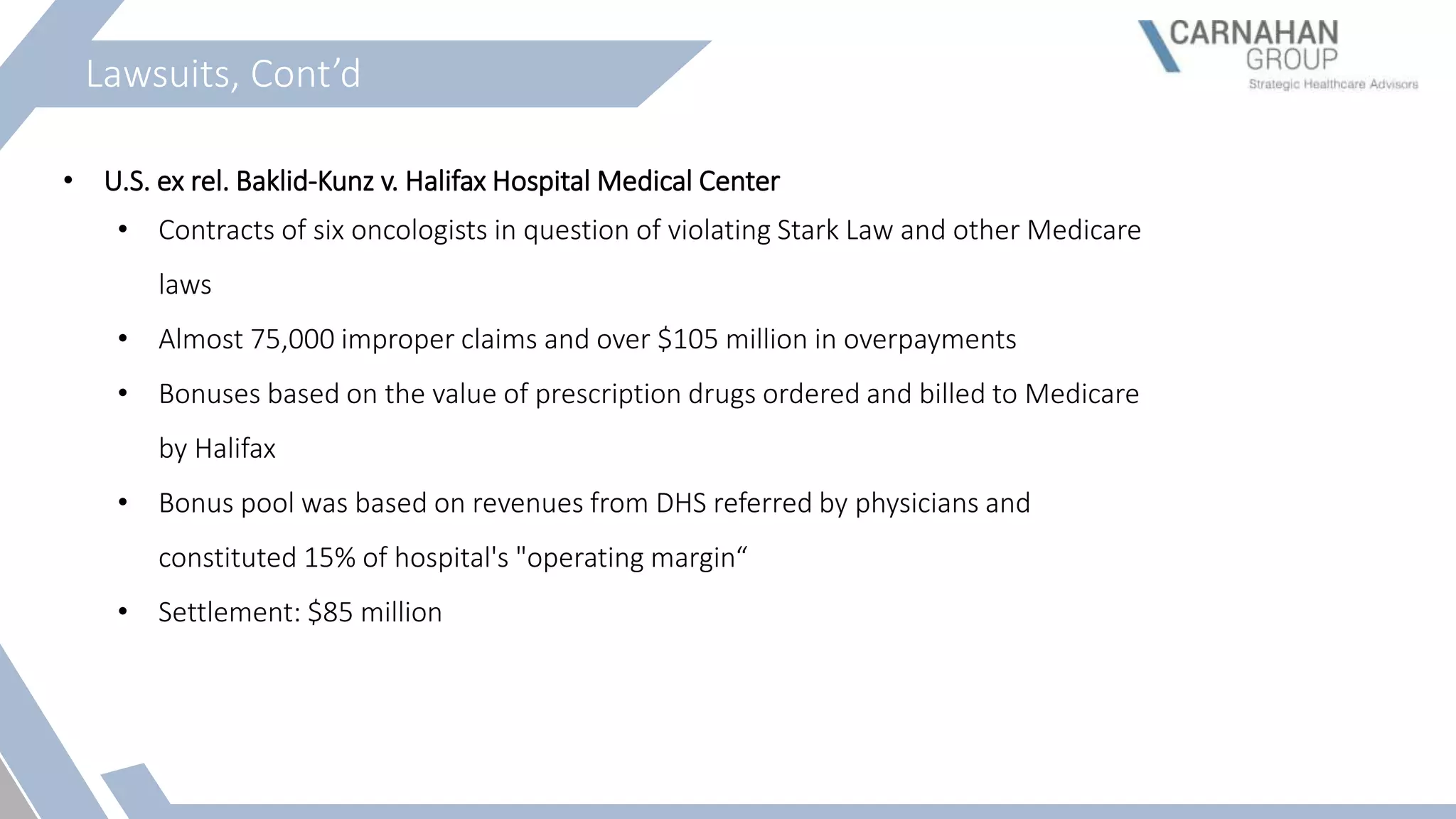

The document discusses the valuation of medical practices when a physician exits, highlighting the expertise of Christopher T. Carnahan, a CPA and business valuation expert with extensive experience in healthcare transactions. It reviews the concept of Fair Market Value (FMV) in healthcare, relevant regulations, and the implications of the Stark Law and Anti-Kickback Statute on physician compensation. Furthermore, it emphasizes the necessity for commercially reasonable contracts and the importance of FMV standards to prevent fraud and ensure compliance within healthcare practices.