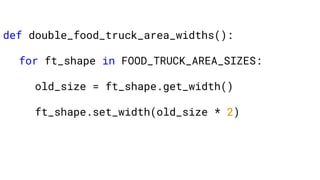

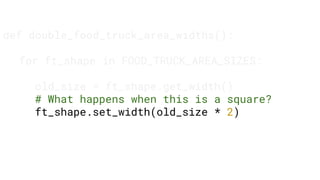

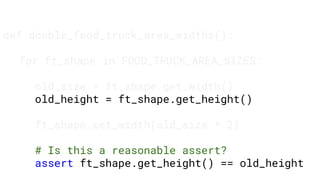

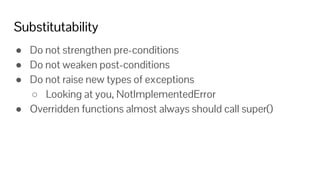

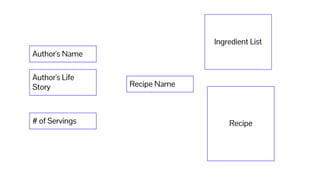

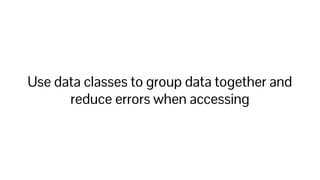

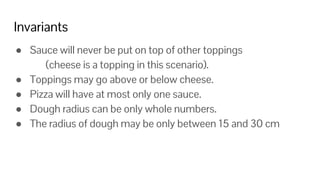

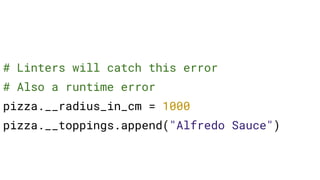

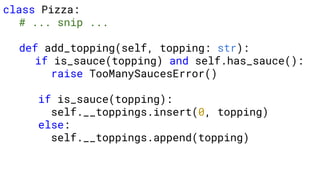

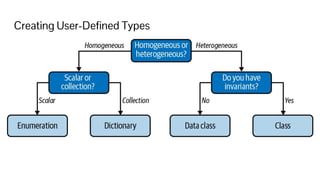

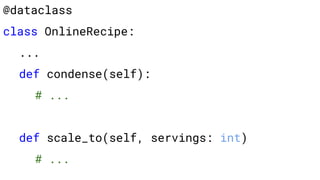

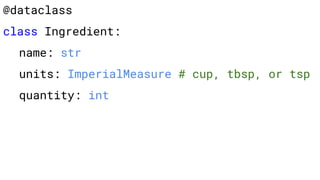

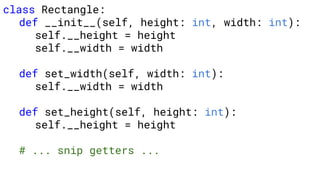

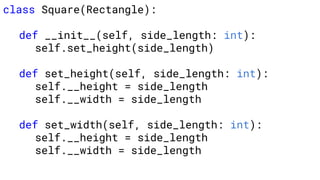

The document discusses the importance of creating a robust and maintainable codebase to facilitate collaboration among developers, focusing on user-defined types, data classes, and invariants. It emphasizes clear communication through code and the responsibilities of developers to minimize future errors and misunderstandings. The talk also explores software design principles, such as inheritance and the Liskov substitution principle, to enhance code quality and coherence.

![def print_receipt(

order: Order,

restaurant: tuple[str, int, str]):

total = (order.subtotal *

(1 + tax[restaurant[2]]))

print(Receipt(restaurant[0], total))](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/user-definedtypes-230422194411-fdbd8759/85/User-Defined-Types-pdf-52-320.jpg)

![def print_receipt(

order: Order,

restaurant: tuple[str, int, str]):

total = (order.subtotal *

(1 + tax[restaurant[2]]))

print(Receipt(restaurant[0], total))](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/user-definedtypes-230422194411-fdbd8759/85/User-Defined-Types-pdf-53-320.jpg)

![def print_receipt(

order: Order,

restaurant: Restaurant):

total = (order.subtotal *

(1 + tax[restaurant.city]))

print(Receipt(restaurant.name, total))](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/user-definedtypes-230422194411-fdbd8759/85/User-Defined-Types-pdf-54-320.jpg)

![def create_daughter_sauce(

mother_sauce: str,

extra_ingredients: list[str]):

# ...

create_daughter_sauce(MOTHER_SAUCE[0],

["Onion"])](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/user-definedtypes-230422194411-fdbd8759/85/User-Defined-Types-pdf-62-320.jpg)

![def create_daughter_sauce(

mother_sauce: str,

extra_ingredients: list[str]):

# ...

# What was MOTHER_SAUCE[0] again?

create_daughter_sauce(MOTHER_SAUCE[0],

["Onion"])](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/user-definedtypes-230422194411-fdbd8759/85/User-Defined-Types-pdf-63-320.jpg)

![def create_daughter_sauce(

mother_sauce: str,

extra_ingredients: list[str]):

# ...

create_daughter_sauce(MOTHER_SAUCE[0],

["Onion"])](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/user-definedtypes-230422194411-fdbd8759/85/User-Defined-Types-pdf-64-320.jpg)

![def create_daughter_sauce(

mother_sauce: str,

extra_ingredients: list[str]):

# ...

create_daughter_sauce("Bechamel",

["Onion"])](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/user-definedtypes-230422194411-fdbd8759/85/User-Defined-Types-pdf-65-320.jpg)

![def create_daughter_sauce(

mother_sauce: str,

extra_ingredients: list[str]):

# ...

create_daughter_sauce("BBQ Sauce",

["Onion"])](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/user-definedtypes-230422194411-fdbd8759/85/User-Defined-Types-pdf-66-320.jpg)

![def create_daughter_sauce(

mother_sauce: str,

extra_ingredients: list[str]):

# ...

create_daughter_sauce("BBQ Sauce",

["Onion"])

Wrong](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/user-definedtypes-230422194411-fdbd8759/85/User-Defined-Types-pdf-67-320.jpg)

![def create_daughter_sauce(

mother_sauce: str,

extra_ingredients: list[str]):

# ...

create_daughter_sauce("Bechamel",

["Onion"])](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/user-definedtypes-230422194411-fdbd8759/85/User-Defined-Types-pdf-68-320.jpg)

![def create_daughter_sauce(

mother_sauce: str,

extra_ingredients: list[str]):

# ...

create_daughter_sauce("Béchamel",

["Onion"])](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/user-definedtypes-230422194411-fdbd8759/85/User-Defined-Types-pdf-69-320.jpg)

![def create_daughter_sauce(

mother_sauce: str,

extra_ingredients: list[str]):

# ...

create_daughter_sauce(MOTHER_SAUCE[0],

["Onion"])](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/user-definedtypes-230422194411-fdbd8759/85/User-Defined-Types-pdf-73-320.jpg)

![def create_daughter_sauce(

mother_sauce: str,

extra_ingredients: list[str]):

# ...

create_daughter_sauce(MOTHER_SAUCE[0],

["Onion"])](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/user-definedtypes-230422194411-fdbd8759/85/User-Defined-Types-pdf-74-320.jpg)

![def create_daughter_sauce(

mother_sauce: MotherSauce,

extra_ingredients: list[str]):

# ...

create_daughter_sauce(MotherSauce.BÉCHAMEL,

["Onion"])](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/user-definedtypes-230422194411-fdbd8759/85/User-Defined-Types-pdf-75-320.jpg)

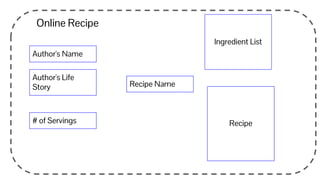

![@dataclass

class OnlineRecipe:

name: str

author_name: str

author_life_story: str

number_of_servings: int

ingredients: list[Ingredient]

recipe: str](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/user-definedtypes-230422194411-fdbd8759/85/User-Defined-Types-pdf-85-320.jpg)

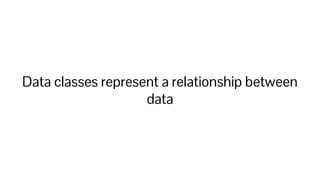

![recipe = OnlineRecipe(

"Pasta With Sausage",

"Pat Viafore",

"When I was 15, I remember ......",

6,

["Rigatoni", ..., "Basil", "Sausage"],

"First, brown the sausage ...."

)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/user-definedtypes-230422194411-fdbd8759/85/User-Defined-Types-pdf-86-320.jpg)

![Heterogeneous data

● Heterogeneous data is data that may be multiple different

types (such as str, int, list[Ingredient], etc.)

● Typically not iterated over -- you access a single field at a time](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/user-definedtypes-230422194411-fdbd8759/85/User-Defined-Types-pdf-89-320.jpg)

![# DO NOT DO THIS

recipe = {

"name": "Pasta With Sausage",

"author": "Pat Viafore",

"story": "When I was 15, I remember ....",

"number_of_servings": 6,

"ingredients": ["Rigatoni", ..., "Basil"],

"recipe": "First, brown the sausage ...."

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/user-definedtypes-230422194411-fdbd8759/85/User-Defined-Types-pdf-90-320.jpg)

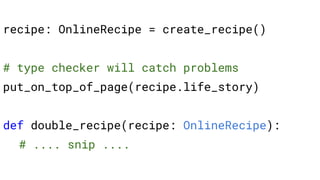

![# is life story the right key name?

put_on_top_of_page(recipe["life_story"])

# What type is recipe?

def double_recipe(recipe: dict):

# .... snip ....](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/user-definedtypes-230422194411-fdbd8759/85/User-Defined-Types-pdf-91-320.jpg)

![@dataclass

class Pizza:

radius_in_cm: int

toppings: list[str]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/user-definedtypes-230422194411-fdbd8759/85/User-Defined-Types-pdf-103-320.jpg)

![pizza = Pizza(15, ["Tomato Sauce",

"Mozzarella",

"Pepperoni"])

# THIS IS BAD!

pizza.radius_in_cm = 1000

pizza.toppings.append("Alfredo Sauce")](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/user-definedtypes-230422194411-fdbd8759/85/User-Defined-Types-pdf-104-320.jpg)

![@dataclass

class Pizza:

radius_in_cm: int

toppings: list[str]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/user-definedtypes-230422194411-fdbd8759/85/User-Defined-Types-pdf-106-320.jpg)

![class Pizza:

def __init__(self, radius_in_cm: int,

toppings: list[str])

assert 15 <= radius_in_cm <= 30

sauces = [t for t in toppings

if is_sauce(t)]

assert len(sauces) <= 1

self.__radius_in_cm = radius_in_cm

sauce = sauces[:1]

self.__toppings = sauce +

[t for t in toppings if not is_sauce(t)]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/user-definedtypes-230422194411-fdbd8759/85/User-Defined-Types-pdf-107-320.jpg)

![class Pizza:

def __init__(self, radius_in_cm: int,

toppings: list[str])

assert 15 <= radius_in_cm <= 30

sauces = [t for t in toppings

if is_sauce(t)]

assert len(sauces) <= 1

self.__radius_in_cm = radius_in_cm

sauce = sauces[:1]

self.__toppings = sauce +

[t for t in toppings if not is_sauce(t)]

INVARIANT

CHECKING](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/user-definedtypes-230422194411-fdbd8759/85/User-Defined-Types-pdf-108-320.jpg)

![# Now an exception

pizza = Pizza(1000, ["Tomato Sauce",

"Mozzarella",

"Pepperoni"])](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/user-definedtypes-230422194411-fdbd8759/85/User-Defined-Types-pdf-109-320.jpg)

![class Pizza:

def __init__(self, radius_in_cm: int,

toppings: list[str])

assert 15 <= radius_in_cm <= 30

sauces = [t for t in toppings

if is_sauce(t)]

assert len(sauces) <= 1

self.__radius_in_cm = radius_in_cm

sauce = sauces[:1]

self.__toppings = sauce +

[t for t in toppings if not is_sauce(t)]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/user-definedtypes-230422194411-fdbd8759/85/User-Defined-Types-pdf-110-320.jpg)

![class Pizza:

def __init__(self, radius_in_cm: int,

toppings: list[str])

assert 15 <= radius_in_cm <= 30

sauces = [t for t in toppings

if is_sauce(t)]

assert len(sauces) <= 1

self.__radius_in_cm = radius_in_cm

sauce = sauces[:1]

self.__toppings = sauce +

[t for t in toppings if not is_sauce(t)]

"Private"

Members](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/user-definedtypes-230422194411-fdbd8759/85/User-Defined-Types-pdf-111-320.jpg)

![@dataclass

class OnlineRecipe:

name: str

author_name: str

author_life_story: str

number_of_servings: int

ingredients: list[Ingredient]

recipe: str](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/user-definedtypes-230422194411-fdbd8759/85/User-Defined-Types-pdf-122-320.jpg)

![FOOD_TRUCK_AREA_SIZES = [

Rectangle(1, 20),

Rectangle(5, 5),

Rectangle(20, 30)

]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/user-definedtypes-230422194411-fdbd8759/85/User-Defined-Types-pdf-161-320.jpg)

![FOOD_TRUCK_AREA_SIZES = [

Rectangle(1, 20),

Rectangle(5, 5),

Rectangle(20, 30)

]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/user-definedtypes-230422194411-fdbd8759/85/User-Defined-Types-pdf-167-320.jpg)

![FOOD_TRUCK_AREA_SIZES = [

Rectangle(1, 20),

Square(5),

Rectangle(20, 30)

]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/user-definedtypes-230422194411-fdbd8759/85/User-Defined-Types-pdf-168-320.jpg)