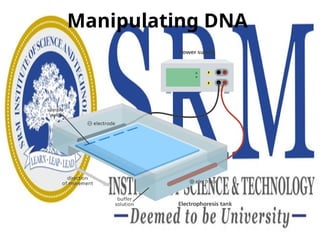

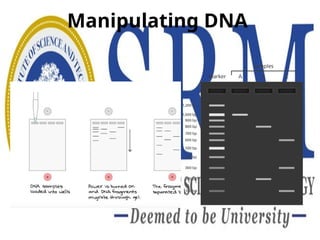

The document discusses DNA computing, a form of molecular computing that uses DNA molecules and biomolecular operations to solve complex problems. It highlights the foundational principles, advantages, and various techniques of DNA manipulation, such as denaturation, annealing, and gel electrophoresis. Moreover, it addresses key questions regarding the computational capabilities and feasibility of designing programmable molecular computers.