This document provides a tutorial on using software resources, mainly the R programming language, to analyze single-case experimental design data. It covers topics such as visual analysis techniques, calculation of nonoverlap indices, regression analyses, randomization tests, simulation modeling, and methods for integrating results across multiple studies. Step-by-step guidance is provided for using R and related packages to conduct these various quantitative analyses and visualize results. Relevant code is included in appendices. Aimed at applied researchers, the tutorial is a guide to computational methods for analyzing single-subject data.

![No

com

m

ercialuse

Single-case data analysis: Resources

3.4 Graph rotation for controlling for baseline trend Manolov, Moeyaert, & Evans

The latter two specifications are based on the information about the number of measurements and the

maximal score obtained. Given that rotating the graph is similar to transforming the data, the exact maximal

value of the Y-axis is not critical (especially in terms of nonoverlap), given that the relative distance between

the measurements is maintained.

# Number of measurements

length(score)

## [1] 19

# Maximal value needed for rescaling

max(score)

## [1] 24.2

A name is given to the axes.

The user needs to click with the on each of the data points in order to retrieve the data and then click

Page 33](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/635a0af9-e378-45de-b512-1e1e88e419b8-160210073243/85/Tutorial-37-320.jpg)

![No

com

m

ercialuse

Single-case data analysis: Resources

6.8 Mean phase difference - percentage and standardized versions Manolov, Moeyaert, & Evans

6.8 Mean phase difference - percentage and standardized versions

Name of the technique: Mean phase difference (MPD-P): percentage version

Authors and suggested readings: The MPD-P was proposed and tested by Manolov and Rochat (2015).

The authors offer the details for this procedure, which modifies the Mean phase difference fitting the baseline

trend in a different way and transforming the result into a percentage. Moreover, this indicator is applicable to

designs that include several AB-comparisons offering both separate estimates and an overall one. The combina-

tion of the individual AB-comparisons is achieved via a weighted average, in which the weight is directly related

to the amount of measurements and inversely related to the variability of effects (i.e., similar to Hershberger et

al.’s [1999] replication effect quantification proposed as a moderator).

Software that can be used: The MPD-P can be implemented via an R code developed by R. Manolov.

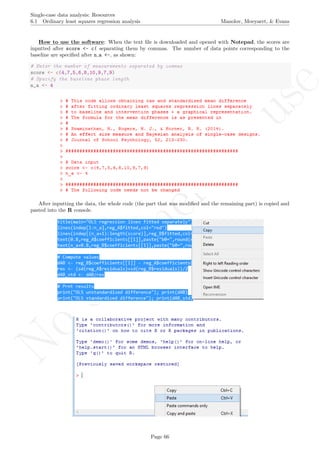

How to obtain the software (percentage version): The R code for applying the MPD (percent) at

the within-studies level is available at https://www.dropbox.com/s/ll25c9hbprro5gz/Within-study_MPD_

percent.R and also in the present document in section 16.14.

After downloading the file, it can easily be manipulated with a text editor such Notepad, apart from more

specific editors like RStudio (http://www.rstudio.com/) or Vim (http://www.vim.org/).

Page 101](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/635a0af9-e378-45de-b512-1e1e88e419b8-160210073243/85/Tutorial-105-320.jpg)

![No

com

m

ercialuse

Single-case data analysis: Resources

6.10 Slope and level change - percentage and standardized versions Manolov, Moeyaert, & Evans

6.10 Slope and level change - percentage and standardized versions

Name of the technique: Slope and level change - percentage version (SLC-P)

Authors and suggested readings: The SLC-P was proposed by Manolov and Rochat (2015) as an ex-

tension of the Slope and level change procedure (Solanas, Manolov, & Onghena, 2010). The authors offer the

details for this procedure. Moreover, this indicator is applicable to designs that include several AB-comparisons

offering both separate estimates and an overall one. The combination of the individual AB-comparisons is

achieved via a weighted average, in which the weight is directly related to the amount of measurements and

inversely related to the variability of effects (i.e., similar to Hershberger et al.’s [1999] replication effect quan-

tification proposed as a moderator).

Software that can be used: The SLC-P can be implemented via an R code developed by R. Manolov.

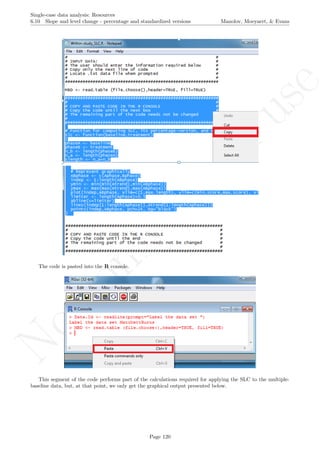

How to obtain the software (percentage version): The R code for applying the SLC (percent) at

the within-studies level is available at https://www.dropbox.com/s/o0ukt01bf6h3trs/Within-study_SLC_

percent.R and also in the present document in section 16.17.

After downloading the file, it can easily be manipulated with a text editor such Notepad, apart from more

specific editors like RStudio (http://www.rstudio.com/) or Vim (http://www.vim.org/).

Page 115](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/635a0af9-e378-45de-b512-1e1e88e419b8-160210073243/85/Tutorial-119-320.jpg)

![No

com

m

ercialuse

Single-case data analysis: Resources

10.0 Application of two-level multilevel models for analysing data Manolov, Moeyaert, & Evans

While installing takes place only once for each package, any package should be loaded when each new R

session is started using the option Load package from the menu Packages.

How to use the software: To illustrate the use of the nlme package, we will focus on the data set analysed

by Baek et al. (2014) and published by Jokel, Rochon, and Anderson (2010). This dataset can be downloaded

from https://www.dropbox.com/s/2yla99epxqufnm7/Two-level%20data.txt?dl=0 and is also available in

the present document in section 15.9. For the ones who prefer using the —SAS code for two-level models

detailed information is provided in Moyaert, Ferron, Beretvas, and Van Den Noortgate (2014).

We digitized the data via Plot Digitizer 2.6.3 (http://plotdigitizer.sourceforge.net) focusing only

on the first two phases in each tier. One explanation for the differences in the results obtained here and in

the aforementioned article may be due to the fact that here we use the R package nlme, whereas Baek and

colleagues used SAS proc mixed [SAS Institute Inc., 1998] and Kenward-Roger estimate of degrees of free-

dom (unlike the nlme package). SAS proc mixed potentially handles missing data differently, which can

potentially affect the estimation of autocorrelation). Thus, the equivalence across programs is an issue yet to be

solved and it needs to be kept in mind when results are obtained with different software. Another explanation

for differences in the results may be due to the fact that we digitized the data ourselves, which does not ensure

that that the scores retrieved by Baek et al. (2014) are exactly the same.

Page 155](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/635a0af9-e378-45de-b512-1e1e88e419b8-160210073243/85/Tutorial-159-320.jpg)

![No

com

m

ercialuse

Single-case data analysis: Resources

10.0 Application of two-level multilevel models for analysing data Manolov, Moeyaert, & Evans

Allowing for the treatment effect on trend to vary across lists implies the following reduction: 68.892−9.038

68.892 =

59.854

68.892 86.88%. Allowing for the average treatment effect to vary across lists implies the following reduction:

65.079−9.038

65.079 = 56.041

65.079 86.11%.

Apart from the numerical results, it is also possible to obtain a graphical representation of the data and of

the model fitted. In the following we present the R code for plotting all data on the same graph, distinguishing

the different cases/tiers with different colours. In order for the code presented below to be used for any dataset,

we now refer to the model as Multilevel.Model instead of Baek.Model and rename the dataset itself from

Jokel to Dataset. We also rename the dependent variable from Percent to the more general Score, as well

as changing List to Case when distinguishing the different cases. Finally, we also continue working only with

the complete rows (i.e., not taking missing data into account).

Multilevel.Model <- Baek.Model

Dataset <- Jokel[complete.cases(Jokel),]

names(Dataset)[names(Dataset)=="Percent"] <- "Score"

names(Dataset)[names(Dataset)=="List"] <- "Case"

From here on, the remaining code can be used by all researchers and is not specific to the dataset used in

the current example. The following two lines of code save the fitted values, according to the model used. The

user has only to change the name of

fit <- fitted(Multilevel.Model)

Dataset <- cbind(Dataset,fit)

The following piece of code is used for assigning colours to the different cases/tiers and it has been created

to handle 3 to 10 cases per study, although it can easily be modified.

tiers <- max(Dataset$Case)

lengths <- c(0,tiers)

for (i in 1:tiers)

lengths[i] <- length(Dataset$Time[Dataset$Case==i])

# Create a vector with the colours to be used

if (tiers == 3) cols <- c("red","green","blue")

if (tiers == 4) cols <- c("red","green","blue","black")

if (tiers == 5) cols <- c("red","green","blue","black",

"grey")

if (tiers == 6) cols <- c("red","green","blue","black",

"grey","orange")

if (tiers == 7) cols <- c("red","green","blue","black",

"grey","orange","violet")

if (tiers == 8) cols <- c("red","green","blue","black",

"grey","orange","violet","yellow")

if (tiers == 9) cols <- c("red","green","blue","black",

"grey","orange","violet","yellow","brown")

if (tiers == 10) cols <- c("red","green","blue","black",

"grey","orange","violet","yellow","brown","pink")

Page 159](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/635a0af9-e378-45de-b512-1e1e88e419b8-160210073243/85/Tutorial-163-320.jpg)

![No

com

m

ercialuse

Single-case data analysis: Resources

10.0 Application of two-level multilevel models for analysing data Manolov, Moeyaert, & Evans

# Create a column with the colors

colors <- rep("col",length(Dataset$Time))

colors[1:lengths[1]] <- cols[1]

sum <- lengths[1]

for (i in 2:tiers)

{

colors[(sum+1):(sum+lengths[i])] <- cols[i]

sum <- sum + lengths[i]

}

Dataset <- cbind(Dataset,colors)

Finally, the numerical values of the coefficients estimated for each case and their graphical representation is

obtained copy-pasting in the R console the following lines of code:

# Print the values of the coefficients estimated

coefficients(Baek.Model)

# Represent the results graphically

plot(Score[Case==1]~Time[Case==1], data=Dataset,

xlab="Time", ylab="Score",

xlim=c(1,max(Dataset$Time)),

ylim=c(min(Dataset$Score),max(Dataset$Score)))

for (i in 1:tiers)

{

points(Score[Case==i]~Time[Case==i], col=cols[i],data=Dataset)

lines(Dataset$Time[Dataset$Case==i],Dataset$fit[Dataset$Case==i],col=cols[i])

}

The graph shows the slightly different intercepts and flat (no trend being modelled) baseline levels. More-

over, the different slopes in the intervention phases are made evident. The amount of across-cases variability

Page 160](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/635a0af9-e378-45de-b512-1e1e88e419b8-160210073243/85/Tutorial-164-320.jpg)

![No

com

m

ercialuse

Single-case data analysis: Resources

10.0 Application of two-level multilevel models for analysing data Manolov, Moeyaert, & Evans

install.packages("lattice") # In case the package has not been installed

require(lattice) # Load

qqmath(ranef(Model.lme4, condVar=TRUE), strip=TRUE)$Case

The caterpillar plot shows that there is considerable variability in all three effects around the estimated

averages. Actually, only the intercept and change in level estimates for the second tier are well represented by

the averages, as their confidence intervals include the average estimates across cases. The values represented in

the caterpillar plot can be reconstructed from the results.

Model.lme4

coefficients(Model.lme4)

coefficients(Model.lme4)$Case[,1] - 34.12

coefficients(Model.lme4)$Case[,2] - 40.92

coefficients(Model.lme4)$Case[,3] - 9.39

In case in your version of R, the previous code does not work, you should try:

Model.lme4

fixef(Model.lme4)

ranef(Model.lme4)

Page 162](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/635a0af9-e378-45de-b512-1e1e88e419b8-160210073243/85/Tutorial-166-320.jpg)

![No

com

m

ercialuse

Single-case data analysis: Resources

11.3 Application of three-level multilevel models for meta-analysing data Manolov, Moeyaert, & Evans

While installing takes place only once for each package, any package should be loaded when each new R

session is started using the option Load package from the menu Packages.

How to use the software& How to interpret the result: To illustrate the use of the nlme package,

we will focus on the data set analysed by Moeyaert, Ferron, Beretvas, and Van Den Noortgate (2014) and pub-

lished by Laski, Charlop, and Schreibman (1988) LeBlanc, Geiger, Sautter, and Sidener (2007), Schreibman,

Stahmer, Barlett, and Dufek (2009), Shrerer and Schreibman (2005), Thorp, Stahmer, and Schreibman (1995),

selecting only the data dealing with appropriate and/or spontaneous speech behaviours. In this case the purpose

is to combine data across several single-case studies and therefore we need to take a three-level structure into

account, that is, measurements are nested within cases and cases in turn are nested within studies. Using the

nlme package, we can take this nested structure into account. In contrast, we previously described the case in

which a two-level model (section ??) is used for analyse the data within a single study.

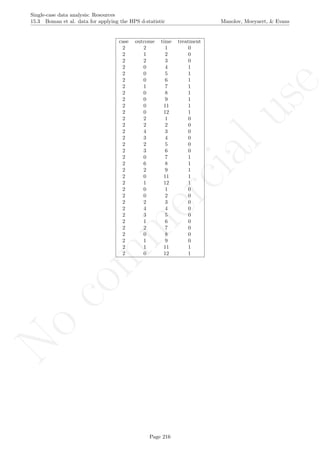

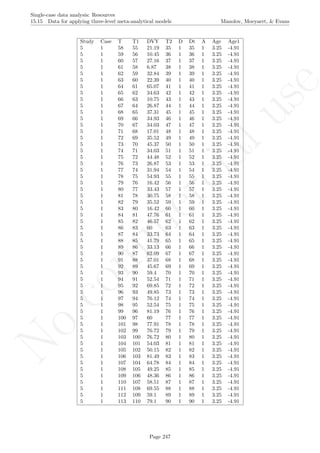

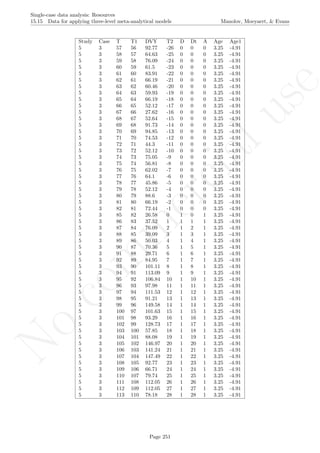

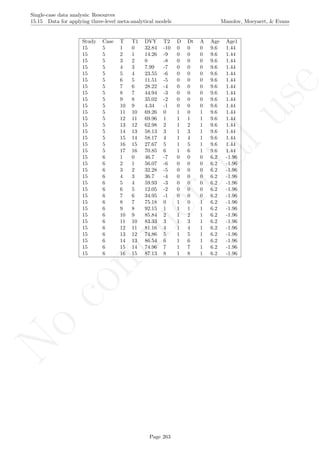

The data are organised in the following way: a) there should be an identified for each different study -

here we used the variable Study in the first column [see an extract of the data table after this explanation];

b) there should also be an identifier for each different case - the variable Case in the second column; c) the

variable T (for time) refers to the measurement occasion; d) the variable T1 refers to time centred around

the first measurement occasion, which is thus equal to 0, with the following measurement occasion taking

the values of 1, 2, 3, ..., until nA + nB − 1, where nA and nB are the lengths of the baseline and treatment

phases, respectively; e) the variable T2 refers to time centred around the first intervention phase measurement

occasion, which is thus equal to 0; in this way the last baseline measurement occasion is denoted by −1,

the penultimate by −2, and so forth down to −nA, whereas the intervention phase measurement occasions

take the numbers 0, 1, 2, 3, ... up to nB − 1; f) the variable DVY is the score of the dependent variable:

the percentage of appropriate and/or spontaneous speech behaviours in this case; g) D is the dummy variable

distinguishing between baseline phase (0) and treatment phase (1); h) Dt is a variable that represents the

interaction between D and T2 and it is used for modelling change in slope; i) Age is a second-level predictor

representing the age of the participants (i.e., the Cases); j) Age1 is the same predictor centred at the average age

of all participants; this centring is performed in order to make the intercept more meaningful, so that it represents

the expected score (percentage of appropriate and/or spontaneous speech behaviours) for the average-aged

individual rather than for individuals with age equal to zero, which would be less meaningful. The dataset can

be downloaded from https://www.dropbox.com/s/e2u3edykupt8nzi/Three-level%20data.txt?dl=0 and in

the present document in section 15.15.

Page 182](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/635a0af9-e378-45de-b512-1e1e88e419b8-160210073243/85/Tutorial-186-320.jpg)

![No

com

m

ercialuse

Single-case data analysis: Resources

12.0 References Manolov, Moeyaert, & Evans

single-case designs. Journal of School Psychology, 52, 213-230.

Swaminathan, H., Rogers, H. J., Horner, R., Sugai, G., & Smolkowski, K. (2014). Regression models for the

analysis of single case designs. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 24, 554-571.

Thorp, D. M., Stahmer, A. C., & Schreibman, L. (1995). The effects of sociodramatic play training on

children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 25, 265-282.

Tukey, J. W. (1977). Exploratory data analysis. London, UK: Addison-Wesley.

Vannest, K. J., Parker, R. I., & Gonen, O. (2011). Single Case Research: web based calculators for SCR

analysis. (Version 1.0) [Web-based application]. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University. Retrieved Friday

12th July 2013. Available from singlecaseresearch.org

Van Den Noortgate, W., & Onghena, P. (2003). Hierarchical linear models for the quantitative integration

of effect sizes in single-case research. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 35, 1-10.

Van den Noortgate, W., & Onghena, P. (2008). A multilevel meta-analysis of single-subject experimental

design studies. Evidence Based Communication Assessment and Intervention, 2, 142-151.

Wehmeyer, M. L., Palmer, S. B., Smith, S. J., Parent, W., Davies, D. K., & Stock, S. (2006). Technology use

by people with intellectual and developmental disabilities to support employment activities: A single-subject

design meta-analysis. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 24, 81-86.

Wendt, O. (2009). Calculating effect sizes for single-subject experimental designs: An overview and compari-

son. Paper presented at The Ninth Annual Campbell Collaboration Colloquium, Oslo, Norway. Retrieved June

29, 2015 from http://www.campbellcollaboration.org/artman2/uploads/1/Wendt_calculating_effect_

sizes.pdf

Winkens, I., Ponds, R., Pouwels-van den Nieuwenhof, C., Eilander, H., & van Heugten, C. (2014). Using

single-case experimental design methodology to evaluate the effects of the ABC method for nursing staff on

verbal aggressive behaviour after acquired brain injury. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 24, 349-364.

Wolery, M., Busick, M., Reichow, B., & Barton, E. E. (2010). Comparison of overlap methods for quantita-

tively synthesizing single-subject data. Journal of Special Education, 44, 18-29.

Page 201](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/635a0af9-e378-45de-b512-1e1e88e419b8-160210073243/85/Tutorial-205-320.jpg)

![No

com

m

ercialuse

Single-case data analysis: Resources

13.0 Appendix A: Some additional information about R Manolov, Moeyaert, & Evans

First, see an example of how different types of arrays (i.e., vectors, two- and three-dimensional matrices) are

defined:

# Assign values to an array: one-dimensional vector

v <- array(c(1,2,3,4,5,6),dim=c(6))

v

## [1] 1 2 3 4 5 6

# Assign values to an array: two-dimensional matrix

m <- array(c(1,2,3,4,5,6),dim=c(2,4))

m

## [,1] [,2] [,3] [,4]

## [1,] 1 3 5 1

## [2,] 2 4 6 2

# Assign values to an array: three-dimensional array

a <- array(c(1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8),dim=c(2,1,3))

a

## , , 1

##

## [,1]

## [1,] 1

## [2,] 2

##

## , , 2

##

## [,1]

## [1,] 3

## [2,] 4

##

## , , 3

##

## [,1]

## [1,] 5

## [2,] 6

Operations can be carried out with the whole vector (e.g., adding 1 to all values) or with different parts of a

vector. These different segments are selected according to the positions that the values have within the vector.

For instance, the second value in the vector x is 7, whereas the segment containing the first and second values

consists of the scalars 2 and 7.

# Create a vector

x <- c(1,6,9)

# Add a constant to all values in the vector

x <- x + 1

x

## [1] 2 7 10

# A scalar within the vector

x[2]

## [1] 7

# A subvector within the vector

x[1:2]

## [1] 2 7

Page 204](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/635a0af9-e378-45de-b512-1e1e88e419b8-160210073243/85/Tutorial-208-320.jpg)

![No

com

m

ercialuse

Single-case data analysis: Resources

13.0 Appendix A: Some additional information about R Manolov, Moeyaert, & Evans

Regarding data input, in R it is possible to open and read a data file (using the function read.table) or to

enter the data manually, creating a data.frame (called here “data1”) consisting of several variables (here only

two: ”studies” and ”grades”). It is possible to work with one of the variables of the data frame or even with a

single value of a variable.

# Manual entry

studies <- c("Humanities", "Humanities", "Sciences", "Sciences")

grades <- c(5,9,7,7)

data1 <- data.frame(studies,grades)

data1

## studies grades

## 1 Humanities 5

## 2 Humanities 9

## 3 Sciences 7

## 4 Sciences 7

# Read an already created data file

data2 <- read.table("C:/Users/WorkStation/Dropbox/data2.txt",header=TRUE)

data2

## studies grades

## 1 Humanities 5

## 2 Humanities 9

## 3 Sciences 7

## 4 Sciences 7

# Refer to one variable within the data set using £

data1$grades

## [1] 5 9 7 7

# Refer to one variable within the data set, when its location is known

data1[2,2]

## [1] 9

Regarding, some of the most useful aspects of programming (loops and conditional statements), an example

is provided below. The code provided computes the average grade for students that have studied Humanities

only (mean h), by first computing the sum h and then dividing it by ppts h (the number of students from this

are). For iteration or looping, the internal function for() is used for reading all the grades, although other

options from the apply family can also be used. For selecting only students of Humanities the conditional

function if() is used.

# Set the counters to zero

sum_h <- 0

ppts_h <- 0

for (i in 1:length(data1$studies))

if(data1$studies[i]=="Humanities")

{

sum_h <- sum_h + data1$grades[i]

ppts_h <- ppts_h + 1

}

#Obtain the mean on the basis of the sum and the number of values (participants)

sum_h

## [1] 14

ppts_h

## [1] 2

Page 205](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/635a0af9-e378-45de-b512-1e1e88e419b8-160210073243/85/Tutorial-209-320.jpg)

![No

com

m

ercialuse

Single-case data analysis: Resources

13.0 Appendix A: Some additional information about R Manolov, Moeyaert, & Evans

mean_h <- sum_h/ppts_h

mean_h

## [1] 7

Regarding user-created functions, below is provided information on how to use a function called “moda”

yielding the modal value of a variable. Such a function needs to be available in the workspace, that is, pasted

into the R console before calling it. Calling itself requires using the function name and the arguments in

parenthesis needed for the function to operate with (here: the array including the values of the variable).

# Enter the data

data3 <- c(1,2,2,3)

# Define the function: this makes it availabe in the workspace

moda <- function(X){

if (is.numeric(X))

moda <- as.numeric(names(table(X))[which(table(X)==max(table(X)))]) else

moda <- names(table(X))[which(table(X)==max(table(X)))]

list(moda=moda,frequency.table=table(X))

}

# Call the user-defined function using the name of the vector with the data

moda(data3)

## $moda

## [1] 2

##

## $frequency.table

## X

## 1 2 3

## 1 2 1

The second example of calling user-defined functions refers to a function called V.Cramer and yielding

a quantification (in terms of Cram´er’s V ) of the strength of relation between to categorical variables. The

arguments required when calling the function are, therefore, two arrays containing the categories of the variables.

# Enter the data

studies <- c("Sciences", "Sciences", "Humanities", "Humanities")

FinalGrades <- c("Excellent", "Excellent", "Excellent", "Very good")

# Define the function: this makes it availabe in the workspace

V.Cramer <- function(X,Y){

tabla <- xtabs(~X+Y)

Cramer <- sqrt(as.numeric(chisq.test(tabla,correct=FALSE)$statistic/

(sum(tabla)*min(dim(tabla)-1))) )

return(V.Cramer=Cramer)

}

# Call the user-defined function using the name of the vector with the data

V.Cramer(studies,FinalGrades)

## [1] 0.5773503

Page 206](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/635a0af9-e378-45de-b512-1e1e88e419b8-160210073243/85/Tutorial-210-320.jpg)

![No

com

m

ercialuse

Single-case data analysis: Resources

16.2 Standard deviation bands Manolov, Moeyaert, & Evans

16.2 Standard deviation bands

After inputting the data actually obtained, the rest of the code is only copied and pasted.

# Input data: values in () separated by commas

# n_a denotes number of baseline phase measurements

score <- c(4,7,5,6,8,10,9,7,9)

n_a <- 4

# Input the standard deviations' rule for creating the bands

SD_value <- 2

# Copy and paste the rest of the code in the R console

# Objects needed for the calculations

size <- length(score)

phaseA <- score[1:n_a]

phaseB <- score[(n_a+1):nsize]

mean_A <- rep(mean(phaseA),n_a)

# Construct bands

band <- sd(phaseA)*SD_value

upper_band <- mean(phaseA) + band

lower_band <- mean(phaseA) - band

# As vectors

upper <- rep(upper_band,nsize)

lower <- rep(lower_band,nsize)

# Counters

count_out_up <- 0

count_out_low <- 0

consec_out_up <- 0

consec_out_low <- 0

greatest_low <- 0

greatest_up <- 0

# Count

for (i in 1:length(phaseB))

{

# Count below

if (phaseB[i] < lower[n_a+i])

{ count_out_low <- count_out_low + 1;

consec_out_low <- consec_out_low + 1} else

{ if(greatest_low < consec_out_low) greatest_low <-

+ consec_out_low;

consec_out_low <- 0; }

if (greatest_low < consec_out_low) greatest_low <-

+ consec_out_low

# Count above

if (phaseB[i] > upper[n_a+i])

{ count_out_up <- count_out_up + 1;

Page 270](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/635a0af9-e378-45de-b512-1e1e88e419b8-160210073243/85/Tutorial-274-320.jpg)

![No

com

m

ercialuse

Single-case data analysis: Resources

16.2 Standard deviation bands Manolov, Moeyaert, & Evans

consec_out_up <- consec_out_up + 1} else

{ if(greatest_up < consec_out_up) greatest_up <-

+ consec_out_up;

consec_out_up <- 0}

if (greatest_up < consec_out_up) greatest_up <-

+ consec_out_up

}

#############################

# Construct the plot with the SD bands

indep <- 1:nsize

# Plot limits

minimal <- min(min(score),min(lower))

maximal <- max(max(score),max(upper))

# Plot data

plot(indep,score, xlim=c(indep[1],indep[length(indep)]),

ylim=c((minimal-1),(maximal+1)), xlab="Measurement time",

ylab="Score", font.lab=2)

lines(indep[1:n_a],score[1:n_a])

lines(indep[(n_a+1):nsize],score[(n_a+1):nsize])

abline (v=(n_a+0.5))

points(indep, score, pch=24, bg="black")

title(main="Standard deviation bands")

# Phase A mean & projections with SD-bands

lines(indep[1:n_a],mean_A)

lines(indep,upper,type="b")

lines(indep,lower,type="b")

# Print information

print("Number of intervention points above upper band");

print(count_out_up)

print("Maximum number of consecutive intervention points

above upper bands");

print(greatest_up)

print("Number of intervention points below lower band");

print(count_out_low)

print("Maximum number of consecutive intervention points

below lower bands");

print(greatest_low)

Page 271](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/635a0af9-e378-45de-b512-1e1e88e419b8-160210073243/85/Tutorial-275-320.jpg)

![No

com

m

ercialuse

Single-case data analysis: Resources

16.2 Standard deviation bands Manolov, Moeyaert, & Evans

Code ends here. Default output of the code below:

2 4 6 8

246810

Measurement time

Score

Standard deviation bands

## [1] "Number of intervention points above upper band"

## [1] 3

## [1] "Maximum number of consecutive intervention points n above upper bands"

## [1] 2

## [1] "Number of intervention points below lower band"

## [1] 0

## [1] "Maximum number of consecutive intervention points n below lower bands"

## [1] 0

Return to main text in the Tutorial about the Standard deviations band: section 3.2.

Page 272](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/635a0af9-e378-45de-b512-1e1e88e419b8-160210073243/85/Tutorial-276-320.jpg)

![No

com

m

ercialuse

Single-case data analysis: Resources

16.3 Estimating and projecting baseline trend Manolov, Moeyaert, & Evans

16.3 Estimating and projecting baseline trend

After inputting the data actually obtained and specifying the rules for constructing the intervals, the rest of

the code is only copied and pasted.

# Input data: values in () separated by commas

# n_a denotes number of baseline phase measurements

score <- c(1,3,5,5,10,8,11,14)

n_a <- 4

# Input the % of the Median to use for constructing the envelope

md_percentage <- 20

# Input the interquartile range to use for constructing the envelope

IQR_value <- 1.5

# Choose figures' display

display<- 'vertical' # Alternatively 'horizontal'

# Copy and paste the rest of the code in the R console

# Objects needed for the calculations

md_addsub <- md_percentage/200

nsize <- length(score)

indep <- 1:nsize

# Construct phase vectors

a1 <- score[1:n_a]

b1 <- score[(n_a+1):nsize]

##############################

# Split-middle method

# Divide the phase into two parts of equal size:

# even number of measuments

if (length(a1)%%2==0)

{

part1 <- 1:(length(a1)/2)

part1 <- a1[1:(length(a1)/2)]

part2 <- ((length(a1)/2)+1):length(a1)

part2 <- a1[((length(a1)/2)+1):length(a1)]

}

# Divide the phase into two parts of equal size:

# odd number of measurements

Page 273](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/635a0af9-e378-45de-b512-1e1e88e419b8-160210073243/85/Tutorial-277-320.jpg)

![No

com

m

ercialuse

Single-case data analysis: Resources

16.3 Estimating and projecting baseline trend Manolov, Moeyaert, & Evans

if (length(a1)%%2==1)

{

part1 <- 1:((length(a1)-1)/2)

part1 <- a1[1:((length(a1)-1)/2)]

part2 <- (((length(a1)+1)/2)+1):length(a1)

part2 <- a1[(((length(a1)+1)/2)+1):length(a1)]

}

# Obtain the median in each section

median1 <- median(part1)

median2 <- median(part2)

# Obtain the midpoint in each section

midp1 <- (length(part1)+1)/2

if (length(a1)%%2==0) midp2 <- length(part1) + (length(part2)+1)/2

if (length(a1)%%2==1) midp2 <- length(part1) + 1 + (length(part2)+1)/2

# Obtain the values of the split-middle trend: "regla de 3"

slope <- (median2-median1)/(midp2-midp1)

sm.trend <- 1:length(a1)

# Whole number function

is.wholenumber <-

function(x, tol = .Machine$double.eps^0.5)

+ abs(x - round(x)) < tol

if (!is.wholenumber(midp1))

{

sm.trend[midp1-0.5] <- median1 - (slope/2)

for (i in 1:length(part1))

if ((midp1-0.5 - i) >= 1) sm.trend[(midp1-0.5 - i)] <-

+ sm.trend[(midp1-0.5-i + 1)] - slope

for (i in (midp1+0.5):length(sm.trend))

sm.trend[i] <- sm.trend[i-1] + slope

}

if (is.wholenumber(midp1))

{

sm.trend[midp1] <- median1

for (i in 1:length(part1))

if ((midp1 - i) >= 1) sm.trend[(midp1 - i)] <-

+ sm.trend[(midp1-i + 1)] - slope

for (i in (midp1+1):length(sm.trend))

sm.trend[i] <- sm.trend[i-1] + slope

}

# Consutructing envelopes

# Construct envelope 20% median (Gast & Spriggs, 2010)

envelope <- median(a1)*md_addsub

upper_env <- 1:length(a1)

upper_env <- sm.trend + envelope

lower_env <- 1:length(a1)

lower_env <- sm.trend - envelope

# Construct envelope 1.5 IQR (add to median)

tukey.eda <- IQR_value*IQR(a1)

upper_IQR <- 1:length(a1)

Page 274](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/635a0af9-e378-45de-b512-1e1e88e419b8-160210073243/85/Tutorial-278-320.jpg)

![No

com

m

ercialuse

Single-case data analysis: Resources

16.3 Estimating and projecting baseline trend Manolov, Moeyaert, & Evans

upper_IQR <- sm.trend + tukey.eda

lower_IQR <- 1:length(a1)

lower_IQR <- sm.trend - tukey.eda

# Project split middle trend and envelope

projected <- 1:length(b1)

proj_env_U <- 1:length(b1)

proj_env_L <- 1:length(b1)

proj_IQR_U <- 1:length(b1)

proj_IQR_L <- 1:length(b1)

projected[1] <- sm.trend[length(sm.trend)]+slope

proj_env_U[1] <- upper_env[length(upper_env)]+slope

proj_env_L[1] <- lower_env[length(lower_env)]+slope

proj_IQR_U[1] <- upper_IQR[length(upper_IQR)]+slope

proj_IQR_L[1] <- lower_IQR[length(lower_IQR)]+slope

for (i in 2:length(b1))

{

projected[i] <- projected[i-1]+slope

proj_env_U[i] <- proj_env_U[i-1]+slope

proj_env_L[i] <- proj_env_L[i-1]+slope

proj_IQR_U[i] <- proj_IQR_U[i-1]+slope

proj_IQR_L[i] <- proj_IQR_L[i-1]+slope

}

# Count the number of values within the envelope

in_env <-0

in_IQR <- 0

for (i in 1:length(b1))

{

if ( (b1[i] >= proj_env_L[i]) && (b1[i] <= proj_env_U[i]) )

in_env <- in_env + 1

if ( (b1[i] >= proj_IQR_L[i]) && (b1[i] <= proj_IQR_U[i]) )

in_IQR <- in_IQR + 1

}

prop_env <- in_env/length(b1)

prop_IQR <- in_IQR/length(b1)

##############################

# Construct the plot with the median-based envelope

if (display=="vertical") {rows <- 2; cols <- 1} else

+ {rows <- 1; cols <- 2}

minimal1 <- min(min(score),min(proj_env_L))

maximal1 <- max(max(score),max(proj_env_U))

par(mfrow=c(rows,cols))

# Plot data

plot(indep,score, xlim=c(indep[1],indep[length(indep)]),

ylim=c((minimal1-1),(maximal1+1)), xlab="Measurement time",

ylab="Score", font.lab=2)

lines(indep[1:n_a],score[1:n_a])

Page 275](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/635a0af9-e378-45de-b512-1e1e88e419b8-160210073243/85/Tutorial-279-320.jpg)

![No

com

m

ercialuse

Single-case data analysis: Resources

16.3 Estimating and projecting baseline trend Manolov, Moeyaert, & Evans

lines(indep[(n_a+1):nsize],score[(n_a+1):nsize])

abline (v=(n_a+0.5))

points(indep, score, pch=24, bg="black")

title(main="Md-based envelope around projected SM trend")

# Split-middle trend & projections with limits

lines(indep[1:n_a],sm.trend[1:n_a])

lines(indep[(n_a+1):nsize],proj_env_U,type="b")

lines(indep[(n_a+1):nsize],proj_env_L,type="b")

# Construct the plot with the IQR-based envelope

minimal2 <- min(min(score),min(proj_IQR_L))

maximal2 <- max(max(score),max(proj_IQR_U))

# Plot data

plot(indep,score, xlim=c(indep[1],indep[length(indep)]),

ylim=c((minimal2-1),(maximal2+1)), xlab="Measurement time",

ylab="Score", font.lab=2)

lines(indep[1:n_a],score[1:n_a])

lines(indep[(n_a+1):nsize],score[(n_a+1):nsize])

abline (v=(n_a+0.5))

points(indep, score, pch=24, bg="black")

title(main="IQR-based envelope around projected SM trend")

# Split-middle trend & projections with limits

lines(indep[1:n_a],sm.trend[1:n_a])

lines(indep[(n_a+1):nsize],proj_IQR_U,type="b")

lines(indep[(n_a+1):nsize],proj_IQR_L,type="b")

# Print information

print("Proportion of phase B data into envelope");

print(prop_env)

print("Proportion of phase B data into IQR limits");

print(prop_IQR)

Page 276](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/635a0af9-e378-45de-b512-1e1e88e419b8-160210073243/85/Tutorial-280-320.jpg)

![No

com

m

ercialuse

Single-case data analysis: Resources

16.3 Estimating and projecting baseline trend Manolov, Moeyaert, & Evans

Code ends here. Default output of the code below:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

051015

Measurement time

Score

Median−based envelope around projected split−middle trend

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

051015

Measurement time

Score

IQR−based envelope around projected split−middle trend

## [1] "Proportion of phase B data into envelope"

## [1] 0

## [1] "Proportion of phase B data into IQR limits"

## [1] 1

Return to main text in the Tutorial about Projecting trend:section 3.3.

Page 277](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/635a0af9-e378-45de-b512-1e1e88e419b8-160210073243/85/Tutorial-281-320.jpg)

![No

com

m

ercialuse

Single-case data analysis: Resources

16.4 Graph rotation for controlling for baseline trend Manolov, Moeyaert, & Evans

16.4 Graph rotation for controlling for baseline trend

After inputting the data actually obtained, the rest of the code is only copied and pasted.

This code requires that the rgl package for R (which it loads). In case it has not been previously installed,

this is achieved in the R console via the following code:

install.packages('rgl')

Once the package is installed, the rest of the code is used, as follows:

# Input data: values in () separated by commas

# n_a denotes number of baseline phase measurements

score <- c(1,3,5,5,10,8,11,14)

n_a <- 4

# Copy and paste the rest of the code in the R console

nsize <- length(score)

tiempo <- 1:nsize

# Construct phase vectors

a1 <- score[1:n_a]

b1 <- score[(n_a+1):nsize]

if (n_a%%3==0)

{

tiempoA <- 1:n_a

corte1 <- quantile(tiempoA,0.33)

corte2 <- quantile(tiempoA,0.66)

final1 <- trunc(corte1)

final2 <- trunc(corte2)

part1.md <- median(score[1:final1])

length.p1 <- final1

times1 <- 1:final1

midp1 <- median(times1)

part2.md <- median(score[(final1+1):final2])

times2 <- (final1+1):final2

midp2 <- median(times2)

part3.md <- median(score[(final2+1):n_a])

times3 <- (final2+1):n_a

midp3 <- median(times3)

}

if (n_a%%3==1)

{

tiempoA <- 1:n_a

corte1 <- quantile(tiempoA,0.33)

corte2 <- quantile(tiempoA,0.66)

final1 <- trunc(corte1)

final2 <- trunc(corte2)

part1.md <- median(score[1:(final1+1)])

length.p1 <- final1+1

Page 278](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/635a0af9-e378-45de-b512-1e1e88e419b8-160210073243/85/Tutorial-282-320.jpg)

![No

com

m

ercialuse

Single-case data analysis: Resources

16.4 Graph rotation for controlling for baseline trend Manolov, Moeyaert, & Evans

times1 <- 1:(final1+1)

midp1 <- median(times1)

part2.md <- median(score[(final1+1):(final2+1)])

times2 <- (final1+1):(final2+1)

midp2 <- median(times2)

part3.md <- median(score[(final2+1):n_a])

times3 <- (final2+1):n_a

midp3 <- median(times3)

}

if (n_a%%3==2)

{

tiempoA <- 1:n_a

corte1 <- quantile(tiempoA,0.33)

corte2 <- quantile(tiempoA,0.66)

final1 <- trunc(corte1)

final2 <- trunc(corte2)

part1.md <- median(score[1:final1])

length.p1 <- final1

times1 <- 1:final1

midp1 <- median(times1)

part2.md <- median(score[(final1+1):final2])

times2 <- (final1+1):final2

midp2 <- median(times2)

part3.md <- median(score[(final2+1):n_a])

times3 <- (final2+1):n_a

midp3 <- median(times3)

}

# Obtain the values of the split-middle trend: "regla de 3"

slope <- (part3.md-part1.md)/(midp3-midp1)

sm.trend <- 1:length(a1)

# Whole number function

is.wholenumber <-

function(x, tol = .Machine$double.eps^0.5)

+ abs(x - round(x)) < tol

if (!is.wholenumber(midp1))

{

sm.trend[midp1-0.5] <- part1.md - (slope/2)

for (i in 1:length.p1)

if ((midp1-0.5 - i) >= 1) sm.trend[(midp1-0.5 - i)] <-

+ sm.trend[(midp1-0.5-i + 1)] - slope

for (i in (midp1+0.5):length(sm.trend))

sm.trend[i] <- sm.trend[i-1] + slope

}

if (is.wholenumber(midp1))

{

sm.trend[midp1] <- part1.md

for (i in 1:length.p1)

if ((midp1 - i) >= 1) sm.trend[(midp1 - i)] <-

+ sm.trend[(midp1-i + 1)] - slope

for (i in (midp1+1):length(sm.trend))

sm.trend[i] <- sm.trend[i-1] + slope

}

# Using the middle part: shifting the trend line

Page 279](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/635a0af9-e378-45de-b512-1e1e88e419b8-160210073243/85/Tutorial-283-320.jpg)

![No

com

m

ercialuse

Single-case data analysis: Resources

16.4 Graph rotation for controlling for baseline trend Manolov, Moeyaert, & Evans

sm.trend.shifted <- 1:length(a1)

midX <- midp2

midY <- part2.md

if (is.wholenumber(midX))

{

sm.trend.shifted[midX] <- midY

for (i in (midX-1):1) sm.trend.shifted[i] <-

+ sm.trend.shifted[i+1] - slope

for (i in (midX+1):n_a) sm.trend.shifted[i] <-

+ sm.trend.shifted[i-1] + slope

}

if (!is.wholenumber(midX))

{

sm.trend.shifted[midX-0.5] <- midY-(0.5*slope)

sm.trend.shifted[midX+0.5] <- midY+(0.5*slope)

for (i in (midX-1.5):1) sm.trend.shifted[i] <-

+ sm.trend.shifted[i+1] - slope

for (i in (midX+1.5):n_a) sm.trend.shifted[i] <-

+ sm.trend.shifted[i-1] + slope

}

# Choosing which trend line to use: shifted or not

# according to which one is closer to 50-50 split

if ( abs(sum(a1 < sm.trend)/n_a - 0.5) <=

+ abs(sum(a1 < sm.trend.shifted)/n_a) )

fitted <- sm.trend

if ( abs(sum(a1 < sm.trend)/n_a - 0.5) >

+ abs(sum(a1 < sm.trend.shifted)/n_a) )

fitted <- sm.trend.shifted

# Project split middle trend

sm.trendB <- rep(0,length(b1))

sm.trendB[1] <- fitted[n_a] + slope

for (i in 2:length(b1))

sm.trendB[i] <- sm.trendB[i-1] + slope

##################################################

# Plot data

plot(tiempo,score, xlim=c(tiempo[1],tiempo[nsize]),

xlab="Measurement time", ylab="Score", font.lab=2,asp=TRUE)

lines(tiempo[1:n_a],score[1:n_a],lty=2)

lines(tiempo[(n_a+1):nsize],score[(n_a+1):nsize],lty=2)

abline (v=(n_a+0.5))

points(tiempo, score, pch=24, bg="black")

# Split-middle trend & projections with limits

lines(tiempo[1:n_a],sm.trend, col="blue")

lines(tiempo[(n_a+1):nsize],sm.trendB, col="blue",

lty="dotted")

interv.pt <- sm.trend[n_a] + slope/2

newslope <- (-1/slope)

y1 <- fitted[1]

x1 <- 1

y2 <- fitted[n_a]

x2 <- n_a

y3 <- interv.pt

Page 280](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/635a0af9-e378-45de-b512-1e1e88e419b8-160210073243/85/Tutorial-284-320.jpg)

![No

com

m

ercialuse

Single-case data analysis: Resources

16.4 Graph rotation for controlling for baseline trend Manolov, Moeyaert, & Evans

x3 <- n_a + 0.5

m <- (y1-y2)/(x1-x2)

if (slope!=0) newslope <- (-1/m) else newslope <- 0

ycut <- -(newslope)*x3 + y3

if (slope!=0) abline(a=ycut,b=newslope, col="red") else

abline(v=n_a+0.5,col="red")

linex <- rep(0,n_a+1)

linex[1] <- n_a+0.5

linex[2:(n_a+1)] <- n_a:1

liney <- rep(0,n_a+1)

liney[1] <- interv.pt

liney[2] <- liney[1] - (newslope/2)

for (i in 3:(n_a+1))

liney[i] <- liney[i-1]-newslope

# Rotating the figure with the "rgl" pacakge

library(rgl)

depth <- rep(0,length(score))

plot3d(x=tiempo, y=score,z=depth,xlab="Measurement occasion",

zlab="0", ylab="Score",size=6, asp="iso")

lines3d(x=tiempo[1:n_a],y=score[1:n_a],z=0,lty=2)

lines3d(x=tiempo[(n_a+1):nsize],y=score[(n_a+1):nsize],z=0,lty=2)

lines3d(x=n_a+0.5, y=min(score):max(score),z=0)

if (slope!=0) lines3d(x=linex, y=liney,z=0, col="red") else

lines3d(x=n_a+0.5, y=min(score):max(score),z=0,col="red")

lines3d(x=tiempo[1:n_a],y=sm.trend, z=0, col="blue")

lines3d(x=tiempo[(n_a+1):nsize],y=sm.trendB, z=0, col="blue")

Page 281](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/635a0af9-e378-45de-b512-1e1e88e419b8-160210073243/85/Tutorial-285-320.jpg)

![No

com

m

ercialuse

Single-case data analysis: Resources

16.5 Pairwise data overlap Manolov, Moeyaert, & Evans

16.5 Pairwise data overlap

After inputting the data actually obtained and specifying the aim of the intervention with respect to the target

behavior, the rest of the code is only copied and pasted.

# Input data: values in () separated by commas

# n_a denotes number of baseline phase measurements

score <- c(5,6,7,5,5,7,7,6,8,9,7)

n_a <- 5

# Specify whether the aim is to increase or reduce the behavior

aim<- 'increase' # Alternatively 'reduce'

# Copy and paste the rest of the code in the R console

# Data manipulations

n_b <- length(score)-n_a

phaseA <- score[1:n_a]

phaseB <- score[(n_a+1):length(score)]

nsize <- length(score)

# Compute overlaps

complete <- 0

half <- 0

if (aim == "increase")

{

for (iter1 in 1:n_a)

for (iter2 in 1:n_b)

{if (phaseA[iter1] > phaseB[iter2]) complete <- complete + 1;

if (phaseA[iter1] == phaseB[iter2]) half <- half + 1}

}

if (aim == "reduce")

{

for (iter1 in 1:n_a)

for (iter2 in 1:n_b)

{if (phaseA[iter1] < phaseB[iter2]) complete <- complete + 1;

if (phaseA[iter1] == phaseB[iter2]) half <- half + 1}

}

comparisons <- n_a*n_b

pdo2 <- (complete/comparisons)**2

# Plot data

indep <- 1:length(score)

plot(indep,score, xlim=c(indep[1],indep[length(indep)]),

xlab="Measurement time", ylab="Score", font.lab=2)

abline (v=(n_a+0.5))

points(indep, score, pch=24, bg="black")

lines(indep[1:n_a],score[1:n_a],lty=2)

lines(indep[(n_a+1):nsize],score[(n_a+1):nsize],lty=2)

Page 283](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/635a0af9-e378-45de-b512-1e1e88e419b8-160210073243/85/Tutorial-287-320.jpg)

![No

com

m

ercialuse

Single-case data analysis: Resources

16.5 Pairwise data overlap Manolov, Moeyaert, & Evans

title(main="Pairwise data overlap")

# Line marking the minimal intervention phase measurement

if (aim == "increase")

{

lineA <- rep(max(phaseA),n_a)

lineB <- rep(min(phaseB),n_b)

}

if (aim == "reduce")

{

lineA <- rep(min(phaseA),n_a)

lineB <- rep(max(phaseB),n_b)

}

# Add lines

lines(indep[1:n_a],lineA)

lines(indep[(n_a+1):length(score)],lineB)

# Print result

print("Pairwise data overlap"); print(pdo2)

Page 284](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/635a0af9-e378-45de-b512-1e1e88e419b8-160210073243/85/Tutorial-288-320.jpg)

![No

com

m

ercialuse

Single-case data analysis: Resources

16.5 Pairwise data overlap Manolov, Moeyaert, & Evans

Code ends here. Default output of the code below:

2 4 6 8 10

56789

Measurement time

Score

Pairwise data overlap

## [1] "Pairwise data overlap"

## [1] 0.001111111

Return to main text in the Tutorial about the Pairwise data overlap: section 4.3.

Page 285](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/635a0af9-e378-45de-b512-1e1e88e419b8-160210073243/85/Tutorial-289-320.jpg)

![No

com

m

ercialuse

Single-case data analysis: Resources

16.6 Percentage of data points exceeding median trend Manolov, Moeyaert, & Evans

16.6 Percentage of data points exceeding median trend

After inputting the data actually obtained and specifying the aim of the intervention with respect to the target

behavior, the rest of the code is only copied and pasted.

# Input data: values in () separated by commas

# n_a denotes number of baseline phase measurements

score <- c(1,3,5,5,10,8,11,14)

n_a <- 4

# Specify whether the aim is to increase or reduce the behavior

aim<- 'increase' # Alternatively 'reduce'

# Copy and paste the rest of the code in the R console

# Objects needed for the calculations

nsize <- length(score)

indep <- 1:nsize

# Construct phase vectors

a1 <- score[1:n_a]

b1 <- score[(n_a+1):nsize]

##############################

# Split-middle method

# Divide the phase into two parts of equal size:

# even number of measm

if (length(a1)%%2==0)

{

part1 <- 1:(length(a1)/2)

part1 <- a1[1:(length(a1)/2)]

part2 <- ((length(a1)/2)+1):length(a1)

part2 <- a1[((length(a1)/2)+1):length(a1)]

}

# Divide the phase into two parts of equal size:

# odd number of measm

if (length(a1)%%2==1)

{

part1 <- 1:((length(a1)-1)/2)

part1 <- a1[1:((length(a1)-1)/2)]

part2 <- (((length(a1)+1)/2)+1):length(a1)

part2 <- a1[(((length(a1)+1)/2)+1):length(a1)]

}

# Obtain the median in each section

median1 <- median(part1)

median2 <- median(part2)

Page 286](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/635a0af9-e378-45de-b512-1e1e88e419b8-160210073243/85/Tutorial-290-320.jpg)

![No

com

m

ercialuse

Single-case data analysis: Resources

16.6 Percentage of data points exceeding median trend Manolov, Moeyaert, & Evans

# Obtain the midpoint in each section

midp1 <- (length(part1)+1)/2

if (length(a1)%%2==0) midp2 <-

+ length(part1) + (length(part2)+1)/2

if (length(a1)%%2==1) midp2 <-

+ length(part1) + 1 + (length(part2)+1)/2

# Obtain the values of the split-middle trend: "regla de 3"

slope <- (median2-median1)/(midp2-midp1)

sm.trend <- 1:length(a1)

# Whole number function

is.wholenumber <-

function(x, tol = .Machine$double.eps^0.5)

+ abs(x - round(x)) < tol

if (!is.wholenumber(midp1))

{

sm.trend[midp1-0.5] <- median1 - (slope/2)

for (i in 1:length(part1))

if ((midp1-0.5 - i) >= 1) sm.trend[(midp1-0.5 - i)] <-

+ sm.trend[(midp1-0.5-i + 1)] - slope

for (i in (midp1+0.5):length(sm.trend))

sm.trend[i] <- sm.trend[i-1] + slope

}

if (is.wholenumber(midp1))

{

sm.trend[midp1] <- median1

for (i in 1:length(part1))

if ((midp1 - i) >= 1) sm.trend[(midp1 - i)] <-

+ sm.trend[(midp1-i + 1)] - slope

for (i in (midp1+1):length(sm.trend))

sm.trend[i] <- sm.trend[i-1] + slope

}

# Project split middle trend

projected <- 1:length(b1)

projected[1] <- sm.trend[length(sm.trend)]+slope

for (i in 2:length(b1))

projected[i] <- projected[i-1]+slope

# Counter the number of intervention points beyond

# (above or below according to aim) trend line

counter <- 0

for (i in 1:length(b1))

{

if ((aim == "increase") && (b1[i] > projected[i]))

counter <- counter + 1

if ((aim == "reduce") && (b1[i] < projected[i]))

counter <- counter + 1

}

pem_t <- (counter/length(b1))*100

# Plot data

plot(indep,score, xlim=c(indep[1],indep[length(indep)]),

Page 287](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/635a0af9-e378-45de-b512-1e1e88e419b8-160210073243/85/Tutorial-291-320.jpg)

![No

com

m

ercialuse

Single-case data analysis: Resources

16.6 Percentage of data points exceeding median trend Manolov, Moeyaert, & Evans

xlab="Measurement time", ylab="Score", font.lab=2)

lines(indep[1:n_a],score[1:n_a],lty=2)

lines(indep[(n_a+1):nsize],score[(n_a+1):nsize],lty=2)

abline (v=(n_a+0.5))

points(indep, score, pch=24, bg="black")

title(main="Data exceeding split-middle trend")

# Split-middle trend

lines(indep[1:n_a],sm.trend[1:n_a])

lines(indep[(n_a+1):nsize],projected[1:(nsize-n_a)])

# Print information

print("Percentage of data points exceeding split-middle trend");

print(pem_t)

Page 288](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/635a0af9-e378-45de-b512-1e1e88e419b8-160210073243/85/Tutorial-292-320.jpg)

![No

com

m

ercialuse

Single-case data analysis: Resources

16.6 Percentage of data points exceeding median trend Manolov, Moeyaert, & Evans

Code ends here. Default output of the code below:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

2468101214

Measurement time

Score

Data exceeding split−middle trend

## [1] "Percentage of data points exceeding split-middle trend"

## [1] 75

Return to main text in the Tutorial about the Percentage of data points exceeding median trend: section

4.7.

Page 289](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/635a0af9-e378-45de-b512-1e1e88e419b8-160210073243/85/Tutorial-293-320.jpg)

![No

com

m

ercialuse

Single-case data analysis: Resources

16.7 Percentage of nonoverlapping corrected data Manolov, Moeyaert, & Evans

16.7 Percentage of nonoverlapping corrected data

After inputting the data actually obtained and specifying the aim of the intervention with respect to the target

behavior, the rest of the code is only copied and pasted.

# Input data: values in () separated by commas

phaseA <- c(9,8,8,7,6,7,7,6,6,5)

phaseB <- c(5,6,4,3,3,6,2,2,2,1)

# Specify whether the aim is to increase or reduce the behavior

aim<- 'increase' # Alternatively 'reduce'

# Copy and paste the rest of the code in the R console

n_a <- length(phaseA)

n_b <- length(phaseB)

# Data correction: phase A

phaseAdiff <- c(1:(n_a-1))

for (iter1 in 1:(n_a-1))

phaseAdiff[iter1] <- phaseA[iter1+1] - phaseA[iter1]

phaseAcorr <- c(1:n_a)

for (iter2 in 1:n_a)

phaseAcorr[iter2] <- phaseA[iter2] - mean(phaseAdiff)*iter2

# Data correction: phase B

phaseBcorr <- c(1:n_b)

for (iter3 in 1:n_b)

phaseBcorr[iter3] <- phaseB[iter3] - mean(phaseAdiff)*(iter3+n_a)

#################################################

# Represent graphically actual and detrended data

A_pred <- rep(0,n_a)

A_pred[1] <- phaseA[1]

for (i in 2:n_a)

A_pred[i] <- A_pred[i-1]+mean(phaseAdiff)

B_pred <- rep(0,n_b)

B_pred[1] <- A_pred[n_a] + mean(phaseAdiff)

for (i in 2:n_b)

B_pred[i] <- B_pred[i-1]+mean(phaseAdiff)

if (aim=="increase") reference <- max(phaseAcorr)

if (aim=="reduce") reference <- min(phaseAcorr)

slength <- n_a + n_b

info <- c(phaseA,phaseB)

time <- c(1:slength)

par(mfrow=c(2,1))

Page 290](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/635a0af9-e378-45de-b512-1e1e88e419b8-160210073243/85/Tutorial-294-320.jpg)

![No

com

m

ercialuse

Single-case data analysis: Resources

16.7 Percentage of nonoverlapping corrected data Manolov, Moeyaert, & Evans

plot(time,info, xlim=c(1,slength), ylim=c((min(info)-1),(max(info)+1)),

xlab="Measurement time", ylab="Variable of interest", font.lab=2)

abline(v=(n_a+0.5))

lines(time[1:n_a],info[1:n_a])

lines(time[1:n_a],A_pred[1:n_a],lty="dashed",col="green")

lines(time[(n_a+1):slength],info[(n_a+1):slength])

lines(time[(n_a+1):slength],B_pred,lty="dashed",col="red")

axis(side=1, at=seq(0,slength,1),labels=TRUE, font=2)

#axis(side=2, at=seq((min(info)-1),(max(info)+1),2),labels=TRUE, font=2)

points(time, info, pch=24, bg="black")

title (main="Original data")

transf <- c(phaseAcorr,phaseBcorr)

plot(time,transf, xlim=c(1,slength), ylim=c((min(transf)-1),(max(transf)+1)),

xlab="Measurement time", ylab="Variable of interest", font.lab=2)

abline(v=(n_a+0.5))

lines(time[1:n_a],transf[1:n_a])

lines(time[1:n_a],rep(reference,n_a),lty="dashed",col="green")

lines(time[(n_a+1):slength],rep(reference,n_b),lty="dashed",col="red")

lines(time[(n_a+1):slength],transf[(n_a+1):slength])

axis(side=1, at=seq(0,slength,1),labels=TRUE, font=2)

#axis(side=2, at=seq((min(transf)-1),(max(transf)+1),2),labels=TRUE, font=2)

points(time, transf, pch=24, bg="black")

title (main="Detrended data")

#####################################################

# PERFORM THE CALCULATIONS AND PRINT THE RESULT

# PND on corrected data: Aim to increase

if (aim == "increase")

{

countcorr <- 0

for (iter4 in 1:n_b)

if (phaseBcorr[iter4] > max(phaseAcorr))

+ countcorr <- countcorr+1

pndcorr <- (countcorr/n_b)*100

print ("The percent of nonoverlapping corrected data is");

print(pndcorr)

}

# PND on corrected data: Aim to reduce

if (aim == "reduce")

{

countcorr <- 0

for (iter4 in 1:n_b)

if (phaseBcorr[iter4] < min(phaseAcorr))

+ countcorr <- countcorr+1

pndcorr <- (countcorr/n_b)*100

print ("The percent of nonoverlapping corrected data is");

print(pndcorr)

}

Page 291](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/635a0af9-e378-45de-b512-1e1e88e419b8-160210073243/85/Tutorial-295-320.jpg)

![No

com

m

ercialuse

Single-case data analysis: Resources

16.7 Percentage of nonoverlapping corrected data Manolov, Moeyaert, & Evans

Code ends here. Default output of the code below:

5 10 15 20

0246810

Measurement time

Variableofinterest

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 11 13 15 17 19

Original data

5 10 15 20

791113

Measurement time

Variableofinterest

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 11 13 15 17 19

Detrended data

## [1] "The percent of nonoverlapping corrected data is"

## [1] 0

Return to main text in the Tutorial about the Percentage of nonoverlapping corrected data: section 4.8.

Page 292](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/635a0af9-e378-45de-b512-1e1e88e419b8-160210073243/85/Tutorial-296-320.jpg)

![No

com

m

ercialuse

Single-case data analysis: Resources

16.8 Percentage of zero data Manolov, Moeyaert, & Evans

16.8 Percentage of zero data

After inputting the data actually obtained, the rest of the code is only copied and pasted.

# Input data: values in () separated by commas

# n_a denotes number of baseline phase measurements

score <- c(7,5,6,7,5,4,0,1,0,2)

n_a <- 5

# Copy and paste the rest of the code in the R console

# Data manipulations

n_b <- length(score)-n_a

phaseA <- score[1:n_a]

phaseB <- score[(n_a+1):length(score)]

# PZD

counter_0 <- 0

counter_after <- 0

for (i in 1:n_b)

{

if (score[n_a+i]==0)

{

counter_0 <- counter_0 + 1

counter_after <- counter_after + 1

}

if ((score[n_a+i]!=0) && (counter_0 !=0))

counter_after <- counter_after + 1

}

# Plot data

indep <- 1:length(score)

plot(indep,score, xlim=c(indep[1],indep[length(indep)]),

xlab="Measurement time", ylab="Score", font.lab=2)

abline (v=(n_a+0.5))

for (i in 1:length(score)) if (score[i] == 0)

points(indep[i], score[i], pch=16, col="red")

for (i in 1:length(score)) if (score[i] != 0)

points(indep[i], score[i], pch=24, bg="black")

lines(indep[1:n_a],score[1:n_a],lty=2)

lines(indep[(n_a+1):length(score)],

score[(n_a+1):length(score)],lty=2)

pzd <- (counter_0 / counter_after)*100

print("Percentage of zero data after first

intervention 0 is achieved"); print(pzd)

Page 293](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/635a0af9-e378-45de-b512-1e1e88e419b8-160210073243/85/Tutorial-297-320.jpg)

![No

com

m

ercialuse

Single-case data analysis: Resources

16.8 Percentage of zero data Manolov, Moeyaert, & Evans

Code ends here. Default output of the code below:

2 4 6 8 10

01234567

Measurement time

Score

## [1] "Percentage of zero data after first intervention 0 is achieved"

## [1] 50

Return to main text in the Tutorial about the Percentage Zero Data: 5.1.

Page 294](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/635a0af9-e378-45de-b512-1e1e88e419b8-160210073243/85/Tutorial-298-320.jpg)

![No

com

m

ercialuse

Single-case data analysis: Resources

16.9 Percentage change index Manolov, Moeyaert, & Evans

16.9 Percentage change index

Percentage change index is the general name for the two indices included in the code. They have also been

called Percentage reduction data (when focusing on the last three measurements for each phase) and Mean

baseline reduction (when using all data).

After inputting the data actually obtained, the rest of the code is only copied and pasted.

# Input data: values in () separated by commas

# n_a denotes number of baseline phase measurements

score <- c(5,6,7,5,5,7,7,6,8,9,7)

n_a <- 5

# Specify whether the aim is to increase or reduce the behavior

aim<- 'increase' # Alternatively 'reduce'

# Copy and paste the rest of the code in the R console

# Data manipulations

n_b <- length(score)-n_a

phaseA <- score[1:n_a]

phaseB <- score[(n_a+1):length(score)]

# Mean baseline reduction

mblr <- ((mean(phaseB)-mean(phaseA))/mean(phaseA))*100

# Percentage reduction data

sum_a <- 0

for (i in (n_a-2):n_a)

sum_a <- sum_a + phaseA[i]

sum_b <- 0

for (i in (n_b-2):n_b)

sum_b <- sum_b + phaseB[i]

prd <- ((sum_b/3 - sum_a/3)/(sum_a/3))*100

# Compute the variance of PRD

mean_a <- sum_a/3

mean_b <- sum_b/3

var_prd <- ( ((var(phaseA)+var(phaseB))/3) +

+ ((mean_a-mean_b)^2/2) )/ var(phaseA)

# Graphical representation

# Plot data

indep <- 1:length(score)

plot(indep,score, xlim=c(indep[1],indep[length(indep)]),

xlab="Measurement time", ylab="Score", font.lab=2)

lines(indep[1:n_a],score[1:n_a],lty=2)

lines(indep[(n_a+1):length(score)],

score[(n_a+1):length(score)],lty=2)

abline (v=(n_a+0.5))

points(indep, score, pch=24, bg="black")

Page 295](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/635a0af9-e378-45de-b512-1e1e88e419b8-160210073243/85/Tutorial-299-320.jpg)

![No

com

m

ercialuse

Single-case data analysis: Resources

16.9 Percentage change index Manolov, Moeyaert, & Evans

title(main="MBLR [blue] + PRD [red]")

# Add lines

lines(indep[1:n_a],rep(mean(phaseA),n_a),col="blue")

lines(indep[(n_a+1):length(score)],

rep(mean(phaseB),n_b),col="blue")

lines(indep[(n_a-2):n_a],rep((sum_a/3),3),

col="red",lwd=3,lty="dashed")

lines(indep[(n_a+n_b-2):length(score)],

rep((sum_b/3),3),col="red",lwd=3)

# Print the results

if (aim == "reduce") {print("Mean baseline reduction");

print(mblr)} else {print("Mean baseline increase");

print(mblr)}

if (aim == "reduce") {print("Percentage reduction data");

print(prd)} else {print("Percentage increase data");

print(prd)}

print("Variance of the Percentage change index = ");

print(var_prd)

Page 296](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/635a0af9-e378-45de-b512-1e1e88e419b8-160210073243/85/Tutorial-300-320.jpg)

![No

com

m

ercialuse

Single-case data analysis: Resources

16.9 Percentage change index Manolov, Moeyaert, & Evans

Code ends here. Default output of the code below:

2 4 6 8 10

56789

Measurement time

Score

MBLR [blue] + PRD [red]

## [1] "Mean baseline increase"

## [1] 30.95238

## [1] "Percentage increase data"

## [1] 41.17647

## [1] "Variance of the Percentage change index = "

## [1] 4.180556

Return to main text in the Tutorial about the Percentage change index (Percentage reduction data and

Mean baseline reduction): section 5.2.

Page 297](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/635a0af9-e378-45de-b512-1e1e88e419b8-160210073243/85/Tutorial-301-320.jpg)

![No

com

m

ercialuse

Single-case data analysis: Resources

16.10 Ordinary least squares regression analysis Manolov, Moeyaert, & Evans

16.10 Ordinary least squares regression analysis

Only the descriptive information (i.e., coefficient estimates) of the OLS regression is used here, not the inferential

information (i.e., statistical significance of these estimates).

After inputting the data actually obtained, the rest of the code is only copied and pasted.

# Input data: values in () separated by commas

# n_a denotes number of baseline phase measurements

score <- c(4,3,3,8,3,5,6,7,7,6)

n_a <- 5

# Copy and paste the rest of the code in the R console

# Create necessary objects

nsize <- length(score)

n_b <- nsize - n_a

phaseA <- score[1:n_a]

phaseB <- score[(n_a+1):nsize]

time_A <- 1:n_a

time_B <- 1:n_b

# Phase A: regressor = time

reg_A <- lm(phaseA ~ time_A)

# Phase B: regressor = time

reg_B <- lm(phaseB ~ time_B)

# Plot data

indep <- 1:length(score)

plot(indep,score, xlim=c(indep[1],indep[length(indep)]),

ylim=c(min(score),max(score)+1/10*max(score)),

xlab="Measurement time", ylab="Score", font.lab=2)

lines(indep[1:n_a],score[1:n_a],lty=2)

lines(indep[(n_a+1):length(score)],

score[(n_a+1):length(score)],lty=2)

abline (v=(n_a+0.5))

points(indep, score, pch=24, bg="black")

title(main="OLS regression lines fitted separately")

lines(indep[1:n_a],reg_A$fitted,col="red")

lines(indep[(n_a+1):length(score)],reg_B$fitted,col="blue")

text(0.8,(max(score)+1/10*max(score)),

paste("b0=",round(reg_A$coefficients[[1]],digits=2),"; ",

"b1=",round(reg_A$coefficients[[2]],digits=2)),

pos=4,cex=0.8,col="red")

text(n_a+0.8,(max(score)+1/10*max(score)),

paste("b0=",round(reg_B$coefficients[[1]],digits=2),"; ",

"b1=",round(reg_B$coefficients[[2]],digits=2)),

pos=4,cex=0.8,col="blue")

# Compute values

dAB <- reg_B$coefficients[[1]] - reg_A$coefficients[[1]] +

(reg_B$coefficients[[2]]-reg_A$coefficients[[2]])*

((n_a+1+n_a + n_b)/2)

res <- sqrt( ((n_a-1)*var(reg_A$residuals) +

(n_b-1)*var(reg_B$residuals)) / (n_a+n_b-2))

dAB_std <- dAB/res

Page 298](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/635a0af9-e378-45de-b512-1e1e88e419b8-160210073243/85/Tutorial-302-320.jpg)

![No

com

m

ercialuse

Single-case data analysis: Resources

16.10 Ordinary least squares regression analysis Manolov, Moeyaert, & Evans

Code ends here. Default output of the code below:

2 4 6 8 10

3456789

Measurement time

Score

OLS regression lines fitted separately

b0= 3.3 ; b1= 0.3 b0= 5.3 ; b1= 0.3

## [1] "OLS unstandardized difference"

## [1] 2

## [1] "OLS standardized difference"

## [1] 1.271283

Return to main text in the Tutorial about the Ordinary least squares effect size: section 6.1.

Page 300](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/635a0af9-e378-45de-b512-1e1e88e419b8-160210073243/85/Tutorial-304-320.jpg)

![No

com

m

ercialuse

Single-case data analysis: Resources

16.11 Piecewise regression analysis Manolov, Moeyaert, & Evans

16.11 Piecewise regression analysis

Only the descriptive information (i.e., coefficient estimates) of the Piecewise regression is used here, not the

inferential information (i.e., statistical significance of these estimates).

After inputting the data actually obtained, the rest of the code is only copied and pasted.

Code for analysis created by Mariola Moeyaert; code for the graphical representation created by Rumen

Manolov.

# Input data: copy-paste line and load/locate the data matrix

Piecewise <- read.table(file.choose(), header=TRUE)

Data matrix aspect as shown below:

## Time Score Phase Time1 Time2 Phase_time2

## 1 4 0 0 -4 0

## 2 7 0 1 -3 0

## 3 5 0 2 -2 0

## 4 6 0 3 -1 0

## 5 8 1 4 0 0

## 6 10 1 5 1 1

## 7 9 1 6 2 2

## 8 7 1 7 3 3

## 9 9 1 8 4 4

# Copy and paste the rest of the code in the R console

# Create necessary objects

nsize <- nrow(Piecewise)

n_a <- 0

for (i in 1:nsize)

if (Piecewise$Phase[i]==0) n_a <- n_a + 1

n_b <- nsize - n_a

phaseA <- Piecewise$Score[1:n_a]

phaseB <- Piecewise$Score[(n_a+1):nsize]

time_A <- 1:n_a

time_B <- 1:n_b

# Unstandardized

# Piecewise regression

reg <- lm(Score ~ Time1 + Phase + Phase_time2, Piecewise)

summary(reg)

res <- sqrt(deviance(reg)/df.residual(reg))

# Compute unstandardized effect sizes

Chance_Level <- reg$coefficients[[3]]

Chance_Slope <- reg$coefficients[[4]]

# Compute standardized effect sizes

Chance_Level_s = reg$coefficients[[3]]/res;

Chance_Slope_s = reg$coefficients[[4]]/res;

# Standardize the results

baseline.scores_std <- rep(0,n_a)

Page 301](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/635a0af9-e378-45de-b512-1e1e88e419b8-160210073243/85/Tutorial-305-320.jpg)

![No

com

m

ercialuse

Single-case data analysis: Resources

16.11 Piecewise regression analysis Manolov, Moeyaert, & Evans

intervention.scores_std <- rep(0,n_b)

for (i in 1:n_a)

baseline.scores_std[i] <- Piecewise$Score[i]/res

for (i in 1:n_b)

intervention.scores_std[i] <- Piecewise$Score[n_a+i]/res

scores_std <- rep(0,nsize)

for (i in 1:nsize)

scores_std[i] <- Piecewise$Score[i]/res

Piecewise_std <- cbind(Piecewise,scores_std)

# Plot data

indep <- 1:nsize

proj <- reg$coefficients[[1]]+reg$coefficients[[2]]*

+ Piecewise$Time1[n_a+1]

plot(indep,Piecewise$Score, xlim=c(indep[1],indep[nsize]),

xlab="Time1", ylab="Score", font.lab=2,xaxt="n")

axis(side=1, at=seq(1,nsize,1),labels=Piecewise$Time1, font=2)

lines(indep[1:n_a],Piecewise$Score[1:n_a],lty=2)

lines(indep[(n_a+1):length(Piecewise$Score)],

Piecewise$Score[(n_a+1):length(Piecewise$Score)],lty=2)

abline (v=(n_a+0.5))

points(indep, Piecewise$Score, pch=24, bg="black")

title(main="Piecewise regression: Unstandardized effects")

lines(indep[1:(n_a+1)],c(reg$fitted[1:n_a],proj),col="red")

lines(indep[(n_a+1):length(Piecewise$Score)],

reg$fitted[(n_a+1):length(Piecewise$Score)],col="red")

text(1,reg$coefficients[[1]],paste(round(reg$coefficients[[1]],

digits=2)),col="blue")

if (n_a%%2 == 0) middle <- n_a/2

if (n_a%%2 == 1) middle <- (n_a+1)/2

lines(indep[middle:(middle+1)],rep(reg$fitted[middle],2),

col="darkgreen")

lines(rep(indep[middle+1],2),reg$fitted[middle:(middle+1)],

col="darkgreen",lwd=4)

text((middle+1.5),(reg$fitted[middle]+0.5*(reg$coefficients[[2]])),

paste(round(reg$coefficients[[2]],digits=2)),col="darkgreen")

if (n_b%%2 == 0) middleB <- n_a + n_b/2

if (n_b%%2 == 1) middleB <- n_a + (n_b+1)/2

lines(indep[middleB:(middleB+1)],rep(reg$fitted[middleB],2),

col="darkgreen")

lines(rep(indep[middleB+1],2),reg$fitted[middleB:(middleB+1)],

col="darkgreen",lwd=4)

lines(indep[middleB:(middleB+1)],

c(reg$fitted[middleB],(reg$fitted[middleB]+(reg$coefficients[[2]]))),

col="green")

lines(rep(indep[middleB+1],2),

c((reg$fitted[middleB]+ (reg$coefficients[[2]])),reg$fitted[middleB]),

col="green",lwd=4)

text((middleB+1.5),

(reg$fitted[middleB]+(reg$coefficients[[2]])),

paste(round(reg$coefficients[[4]],digits=2)),col="red")

text((middleB+1.5),

(reg$fitted[middleB]+0.5*(reg$coefficients[[4]])),

paste(round((reg$coefficients[[4]]+reg$coefficients[[2]]),

digits=2)),col="darkgreen")

lines(rep(indep[n_a+1],2),c(proj,reg$fitted[n_a+1]),col="blue",lwd=4)

Page 302](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/635a0af9-e378-45de-b512-1e1e88e419b8-160210073243/85/Tutorial-306-320.jpg)

![No

com

m

ercialuse

Single-case data analysis: Resources

16.11 Piecewise regression analysis Manolov, Moeyaert, & Evans

text((n_a+1.5),(proj+0.5*(reg$fitted[n_a+1]-proj)),

paste(round(reg$coefficients[[3]],digits=2)),col="blue")

# Print standardized data

print("Standardized baseline data");

print(baseline.scores_std)

print("Standardized intervention phase data");

print(intervention.scores_std)

write.table(Piecewise_std, "Standardized_data.txt",

sep="t",row.names=FALSE)

# Print results

print("Piecewise unstandardized immediate treatment effect");

print(Chance_Level)

print("Piecewise unstandardized change in slope");

print(Chance_Slope)

# Print results

print("Piecewise standardized immediate treatment effect");

print(Chance_Level_s)

print("Piecewise standardized change in slope");

print(Chance_Slope_s)

Page 303](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/635a0af9-e378-45de-b512-1e1e88e419b8-160210073243/85/Tutorial-307-320.jpg)

![No

com

m

ercialuse

Single-case data analysis: Resources

16.11 Piecewise regression analysis Manolov, Moeyaert, & Evans

Code ends here. Default output of the code below:

##

## Call:

## lm(formula = Score ~ Time1 + Phase + Phase_time2, data = Piecewise)

##

## Residuals:

## 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

## -0.9 1.7 -0.7 -0.1 -0.8 1.3 0.4 -1.5 0.6

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) 4.9000 1.1411 4.294 0.00776 **

## Time1 0.4000 0.6099 0.656 0.54091

## Phase 2.3000 1.9764 1.164 0.29703

## Phase_time2 -0.5000 0.7470 -0.669 0.53293

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 1.364 on 5 degrees of freedom

## Multiple R-squared: 0.7053,Adjusted R-squared: 0.5285

## F-statistic: 3.988 on 3 and 5 DF, p-value: 0.08529

## [1] " "

Page 304](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/635a0af9-e378-45de-b512-1e1e88e419b8-160210073243/85/Tutorial-308-320.jpg)

![No

com

m

ercialuse

Single-case data analysis: Resources

16.11 Piecewise regression analysis Manolov, Moeyaert, & Evans

45678910

Time1

Score

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

Piecewise regression: Unstandardized effects

4.9

0.4

−0.5

−0.1

2.3

## [1] "Standardized baseline data"

## [1] 2.932942 5.132649 3.666178 4.399413

## [1] "Standardized intervention phase data"

## [1] 5.865885 7.332356 6.599120 5.132649 6.599120

## [1] " "

## [1] "Piecewise unstandardized immediate treatment effect"

## [1] 2.3

## [1] "Piecewise unstandardized change in slope"

## [1] -0.5

## [1] " "

## [1] "Piecewise standardized immediate treatment effect"

## [1] 1.686442

## [1] "Piecewise standardized change in slope"

## [1] -0.3666178

Document with standardized data also created:

Return to main text in the Tutorial about the Piecewise regression effect size: section 6.2.

Page 305](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/635a0af9-e378-45de-b512-1e1e88e419b8-160210073243/85/Tutorial-309-320.jpg)

![No

com

m

ercialuse

Single-case data analysis: Resources

16.12 Generalized least squares regression analysis Manolov, Moeyaert, & Evans

16.12 Generalized least squares regression analysis

Only the descriptive information (i.e., coefficient estimates) of the GLS regression is used here, not the inferential

information (i.e., statistical significance of these estimates). Statistical significance is only tested for the residuals

via the Durbin-Watson test.

After inputting the data actually obtained, the rest of the code is only copied and pasted.

This code requires that the lmtest package for R (which it loads). In case it has not been previously installed,

this is achieved in the R console via the following code:

install.packages('lmtest')

Once the package is installed, the rest of the code is used, as follows:

# Input data: values in () separated by commas

# n_a denotes number of baseline phase measurements

score <- c(4,7,5,6,8,10,9,7,9)

n_a <- 4

# Choose how to deal with autocorrelation

# "directly" - uses the Cochran-Orcutt estimation

# and transforms data prior to using them as in

# Generalized least squares by Swaminathan et al. (2010)

# "ifsig" - uses Durbin-Watson test and only if the

# transforms data, as in Autoregressive analysis by Gorsuch (1983)