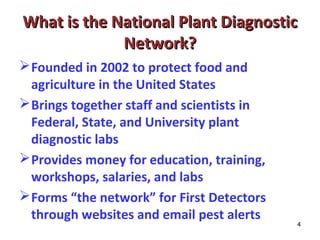

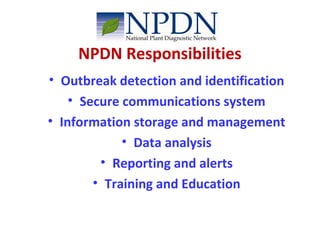

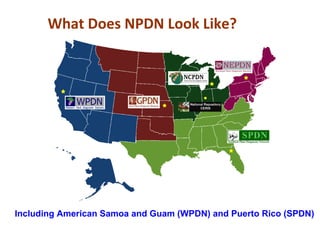

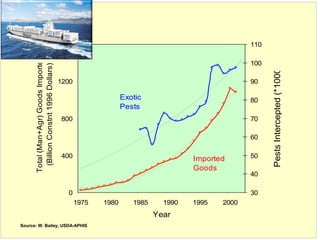

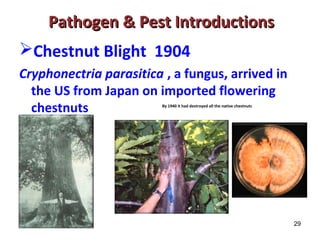

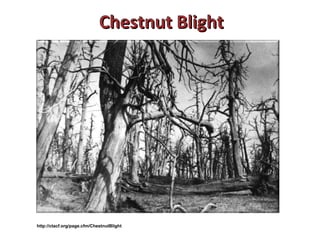

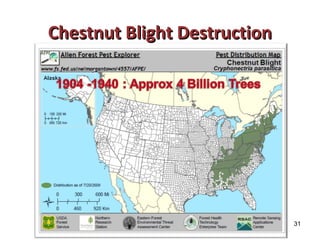

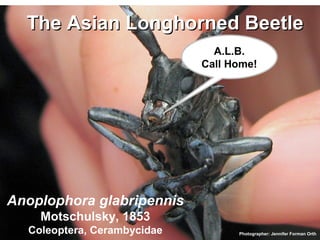

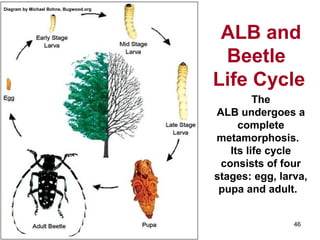

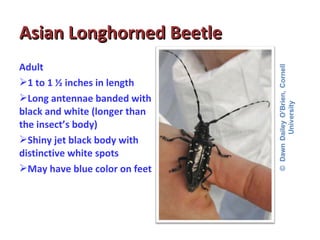

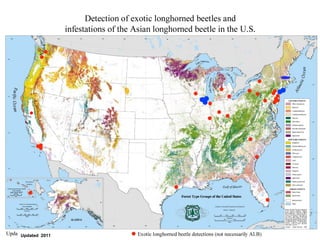

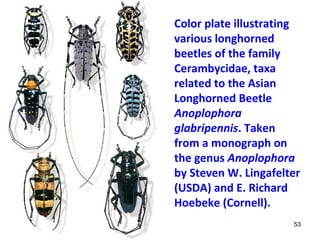

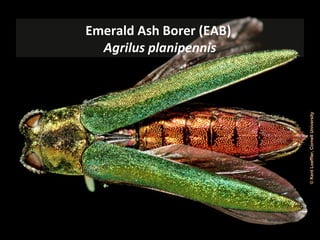

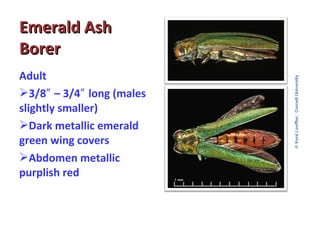

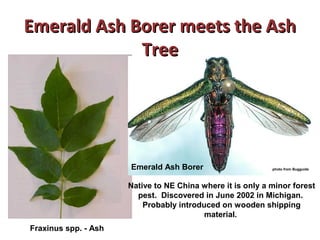

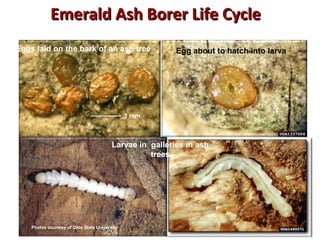

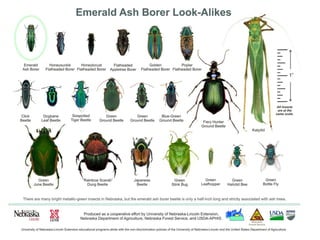

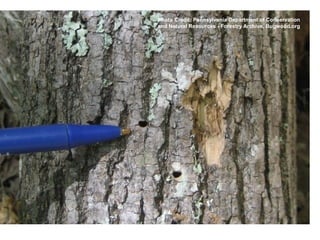

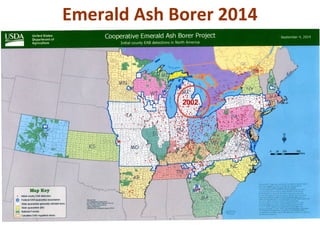

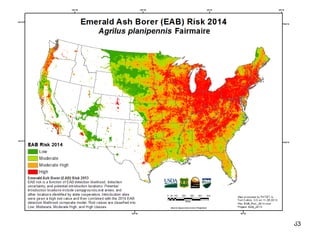

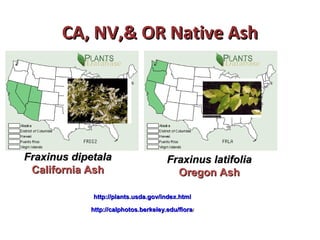

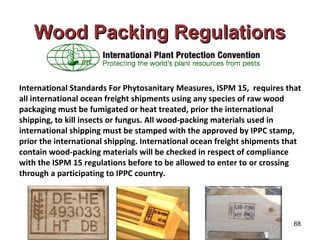

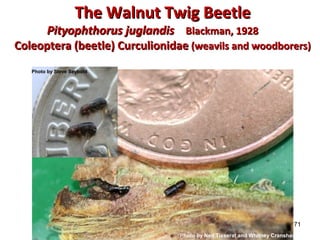

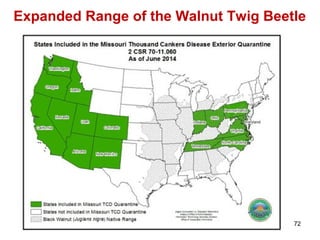

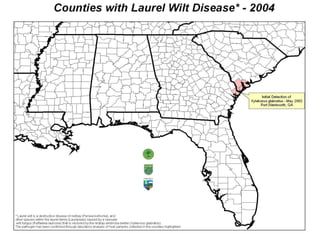

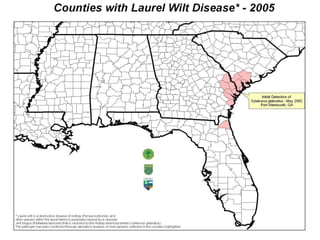

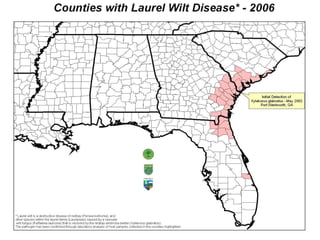

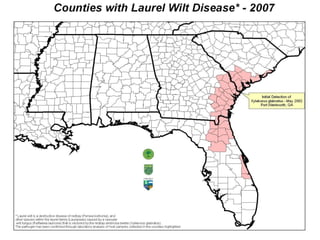

This document summarizes a seminar on trees and drought held in Reno, Nevada on September 26, 2014. It discusses the National Plant Diagnostic Network (NPDN), their role in invasive pest detection and identification, and examples of invasive pests that have caused damage, including the Asian Longhorned Beetle and Emerald Ash Borer. The seminar provided training to attendees so they could become registered First Detectors to help monitor for invasive species through the NPDN.