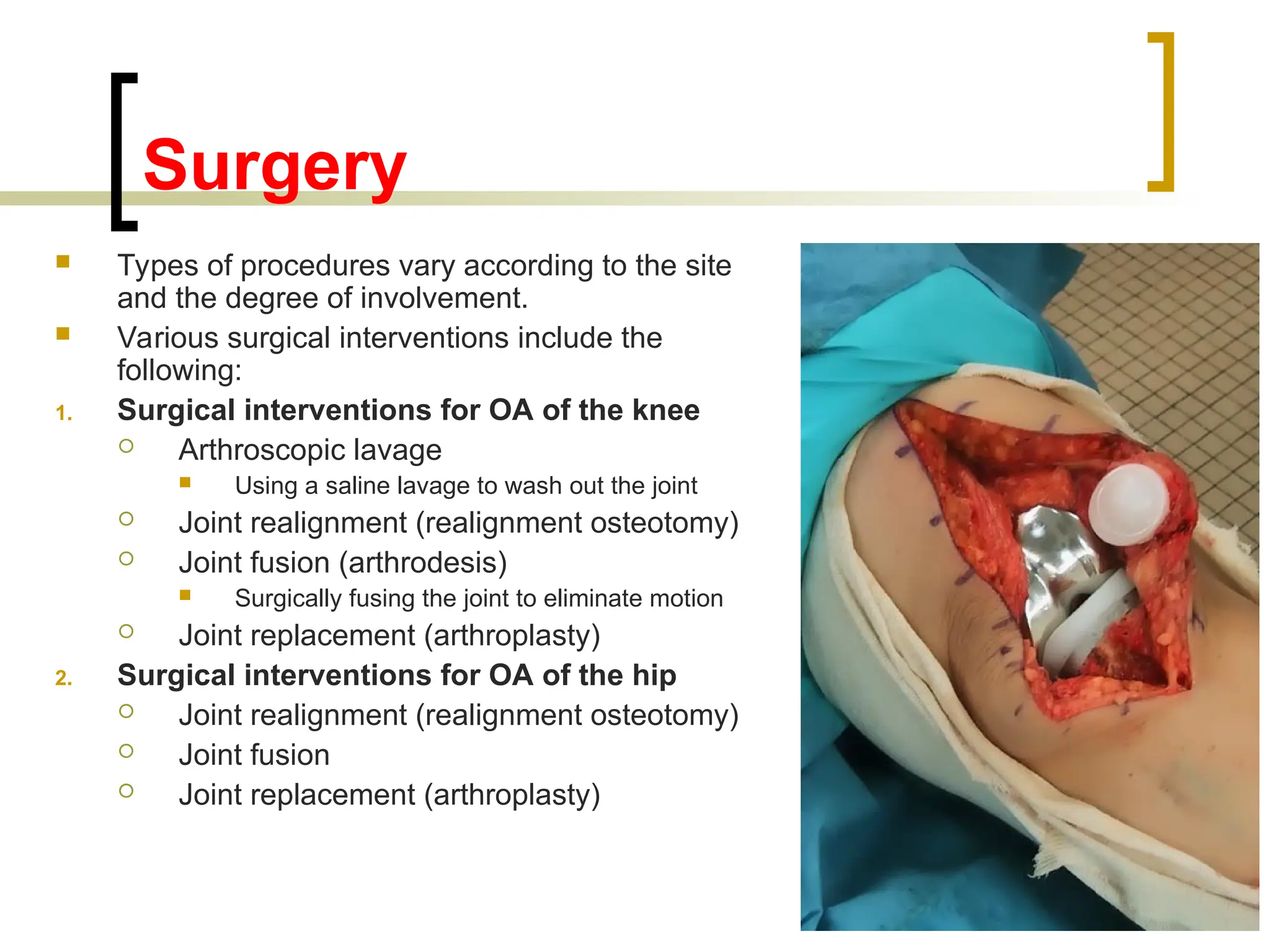

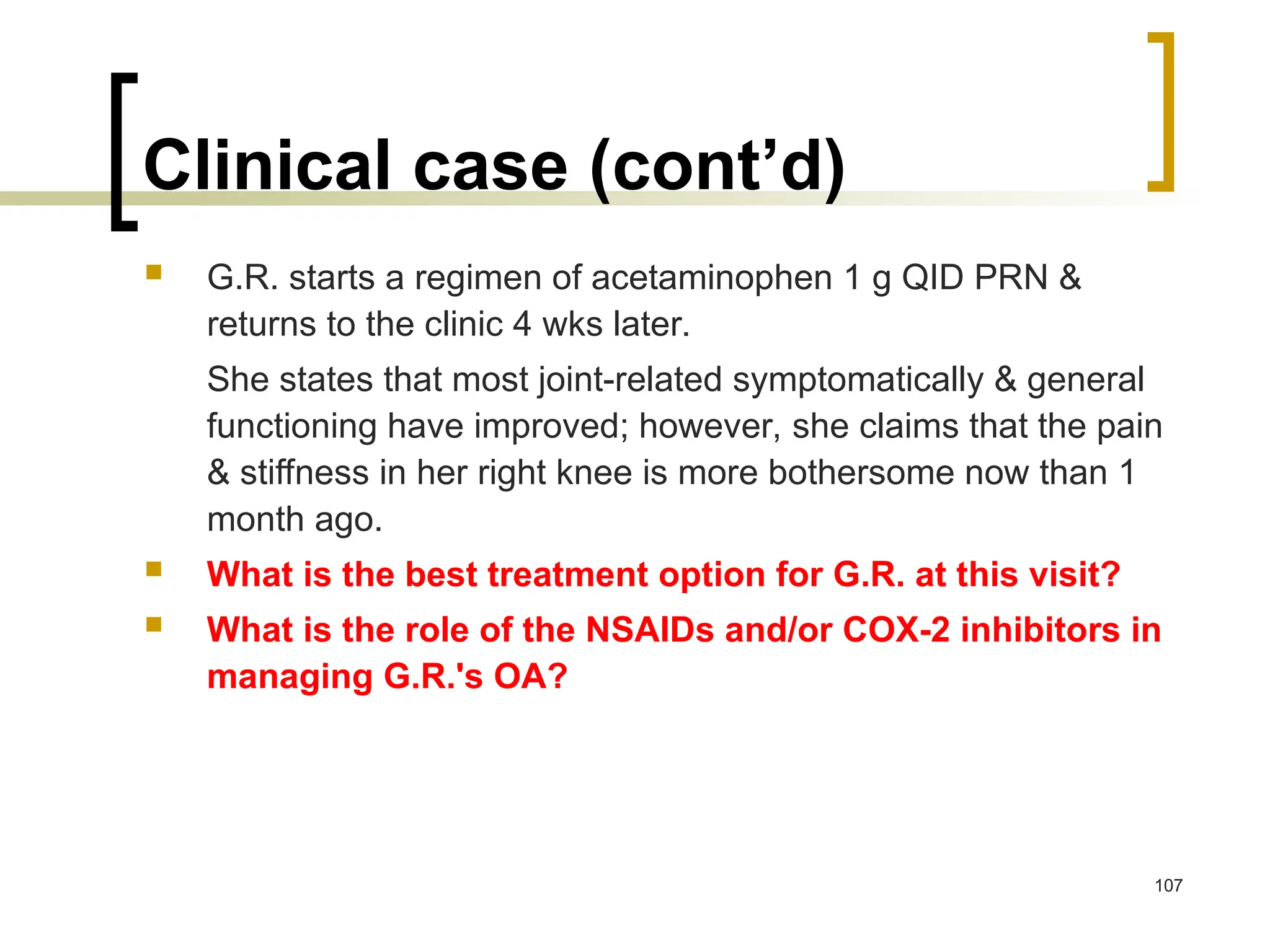

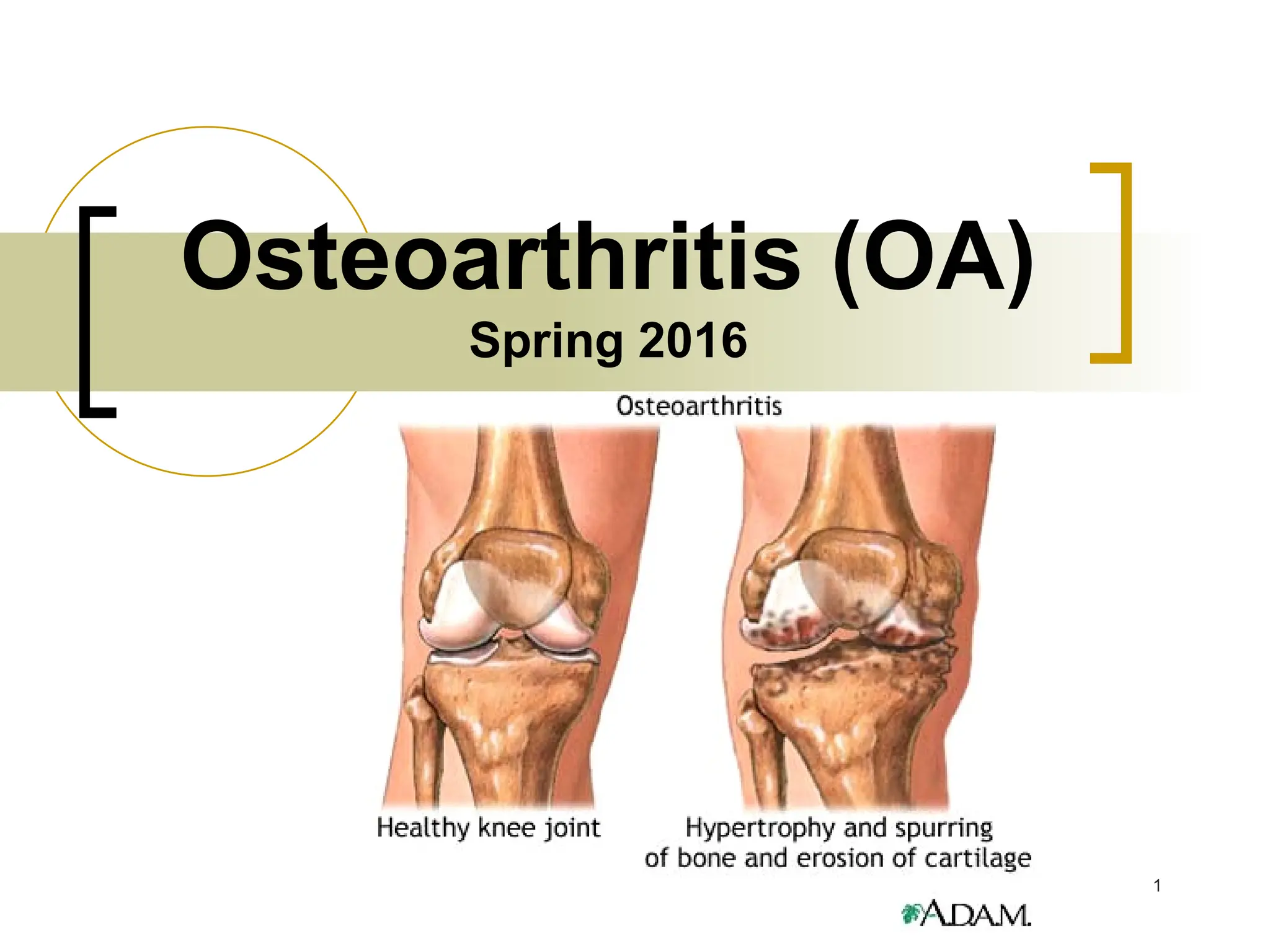

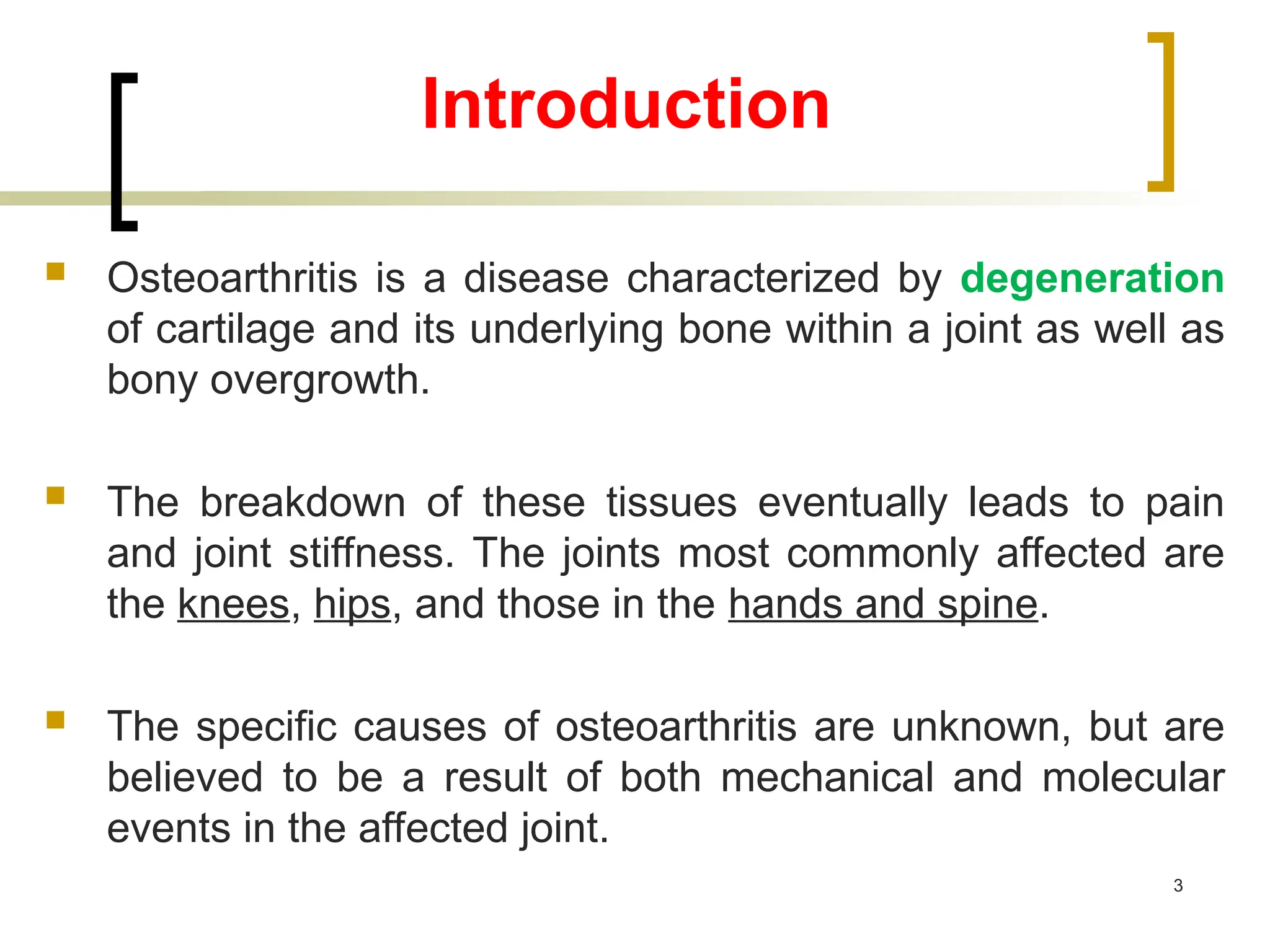

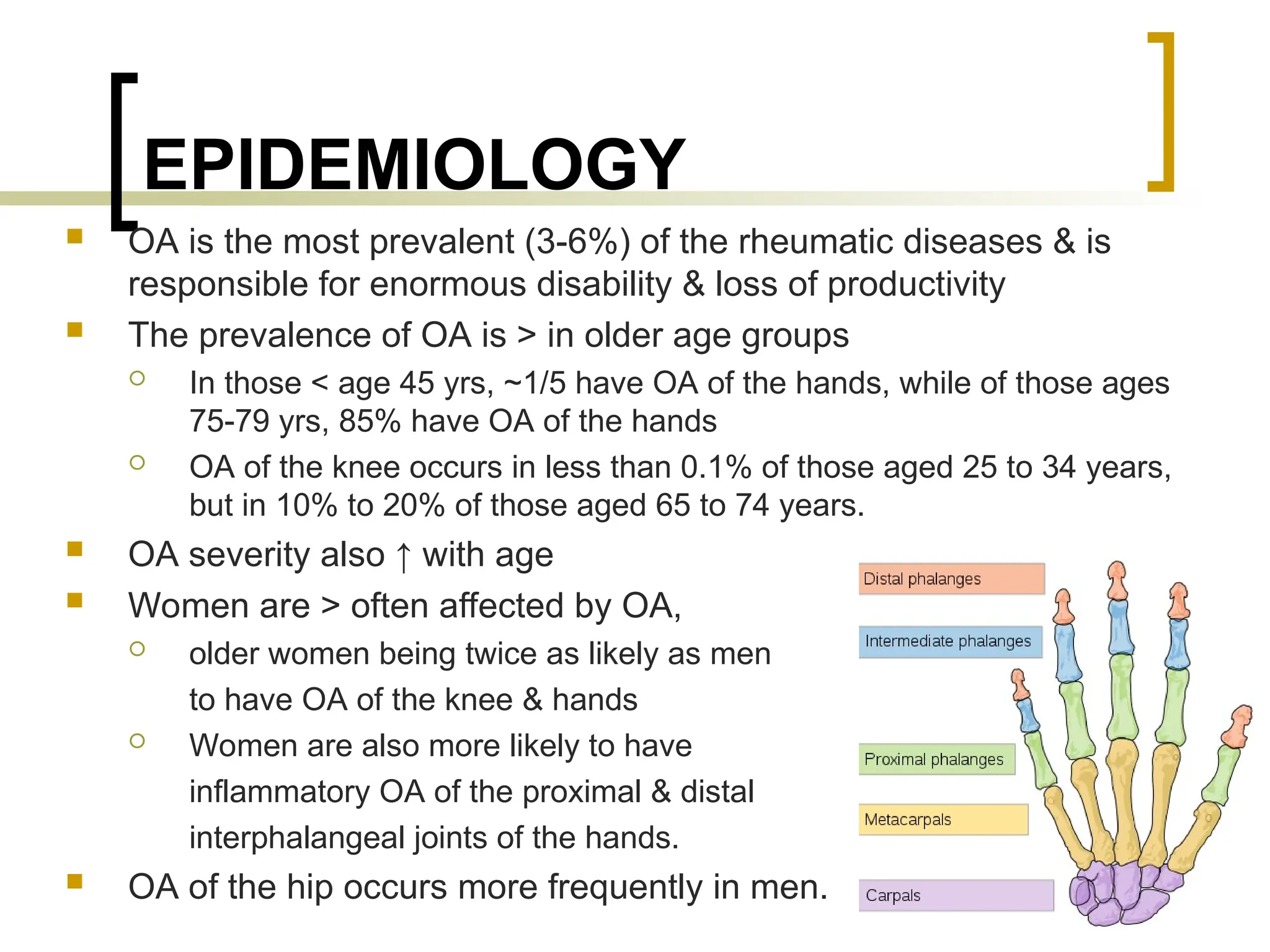

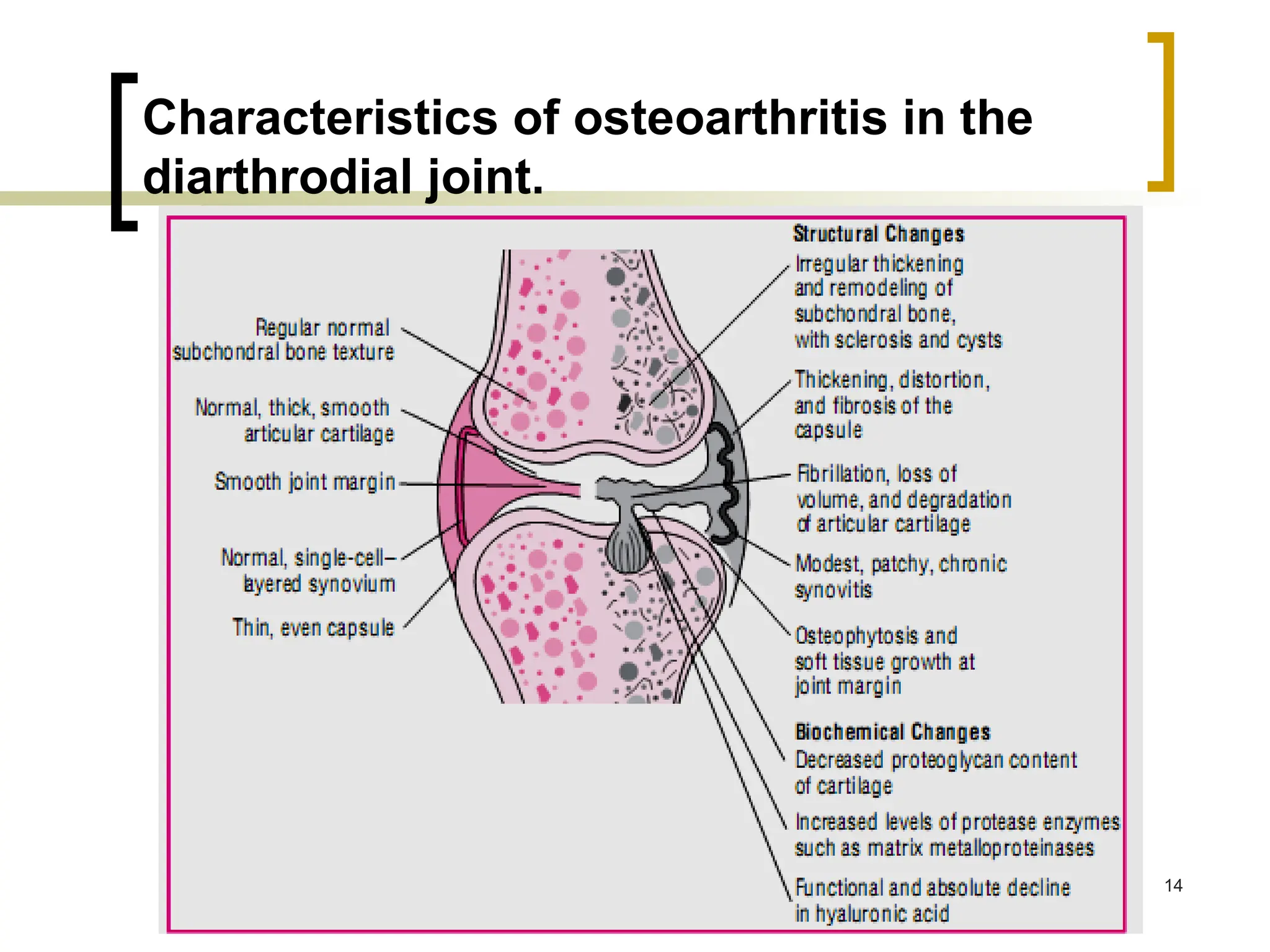

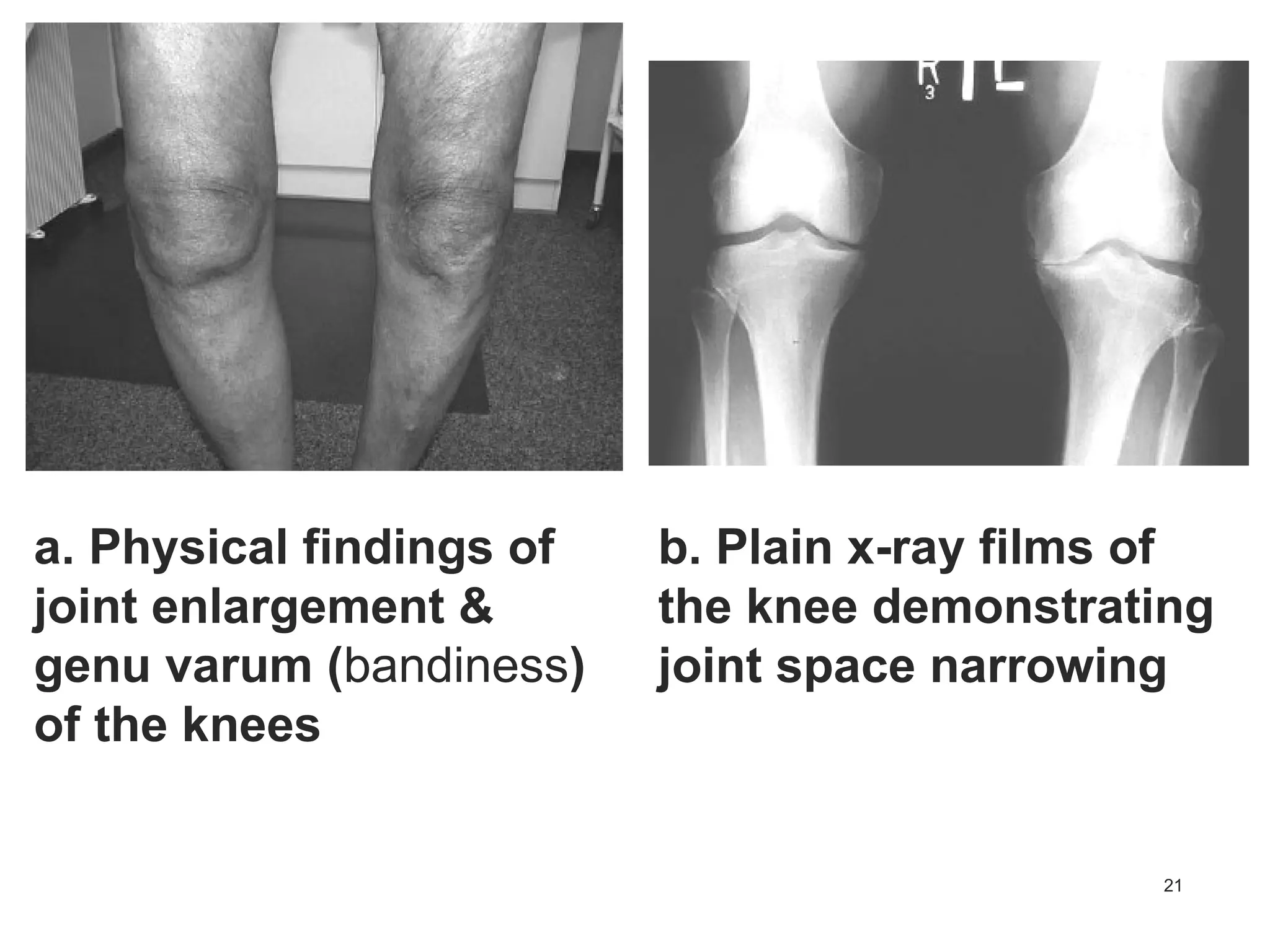

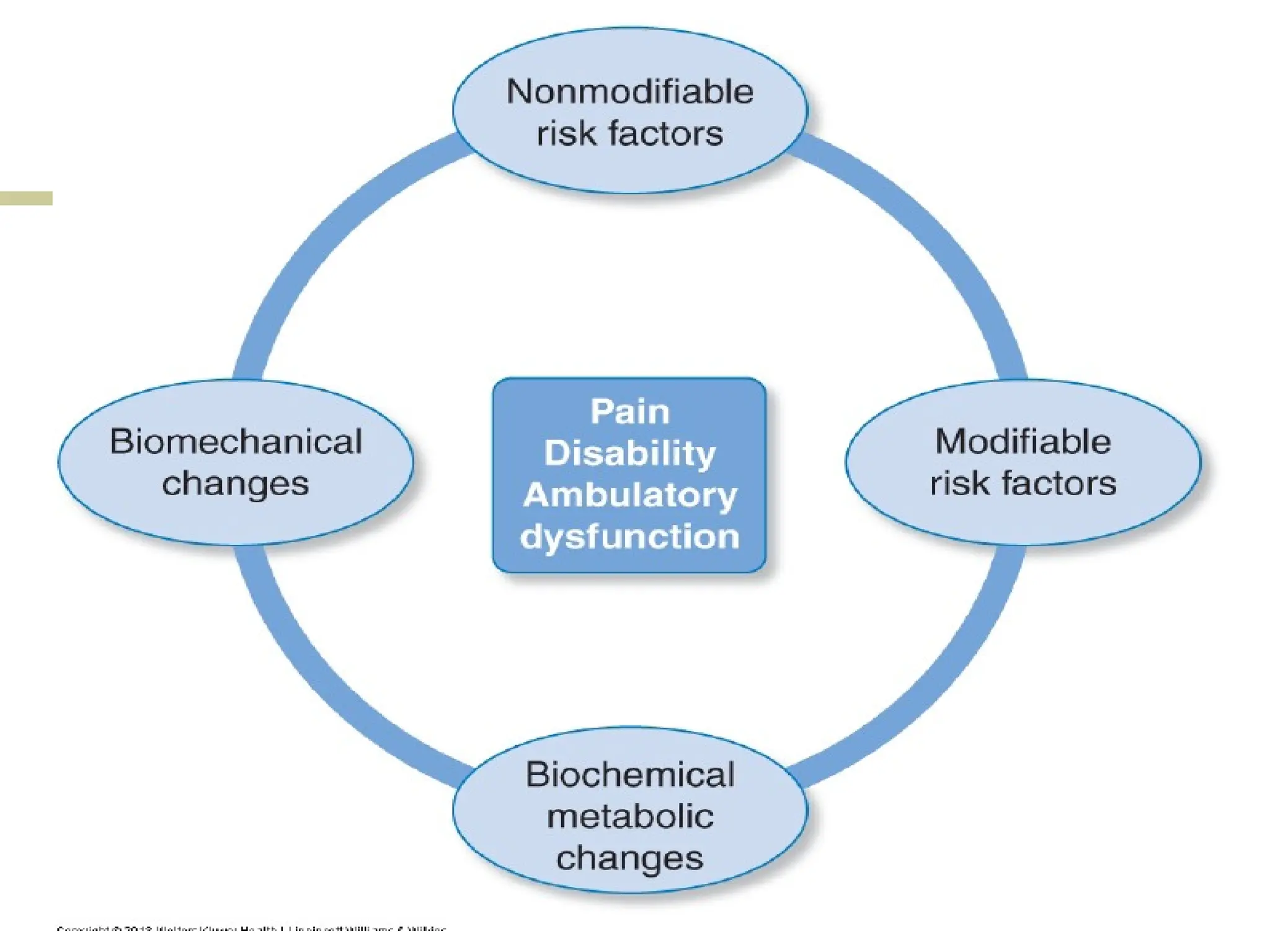

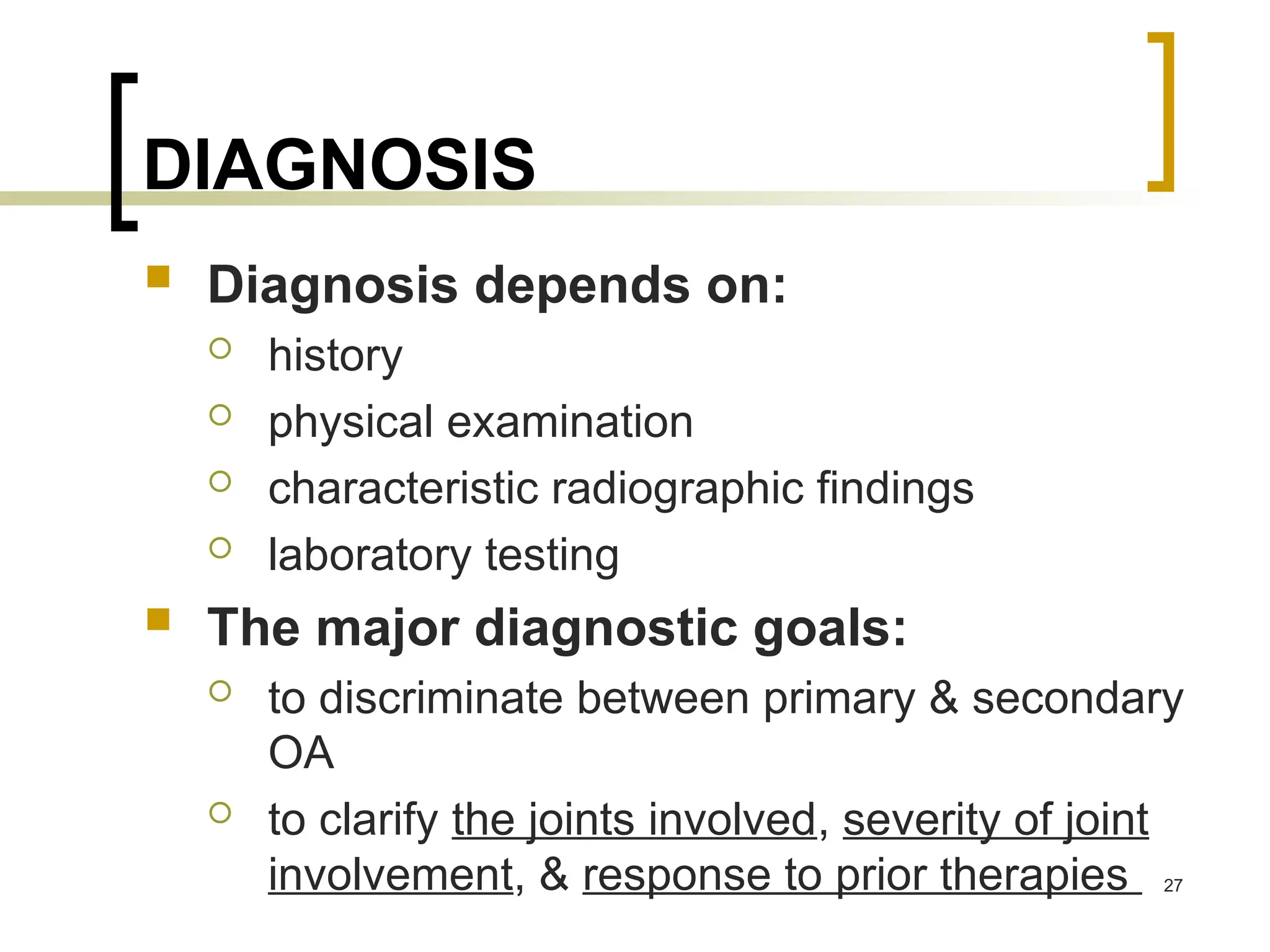

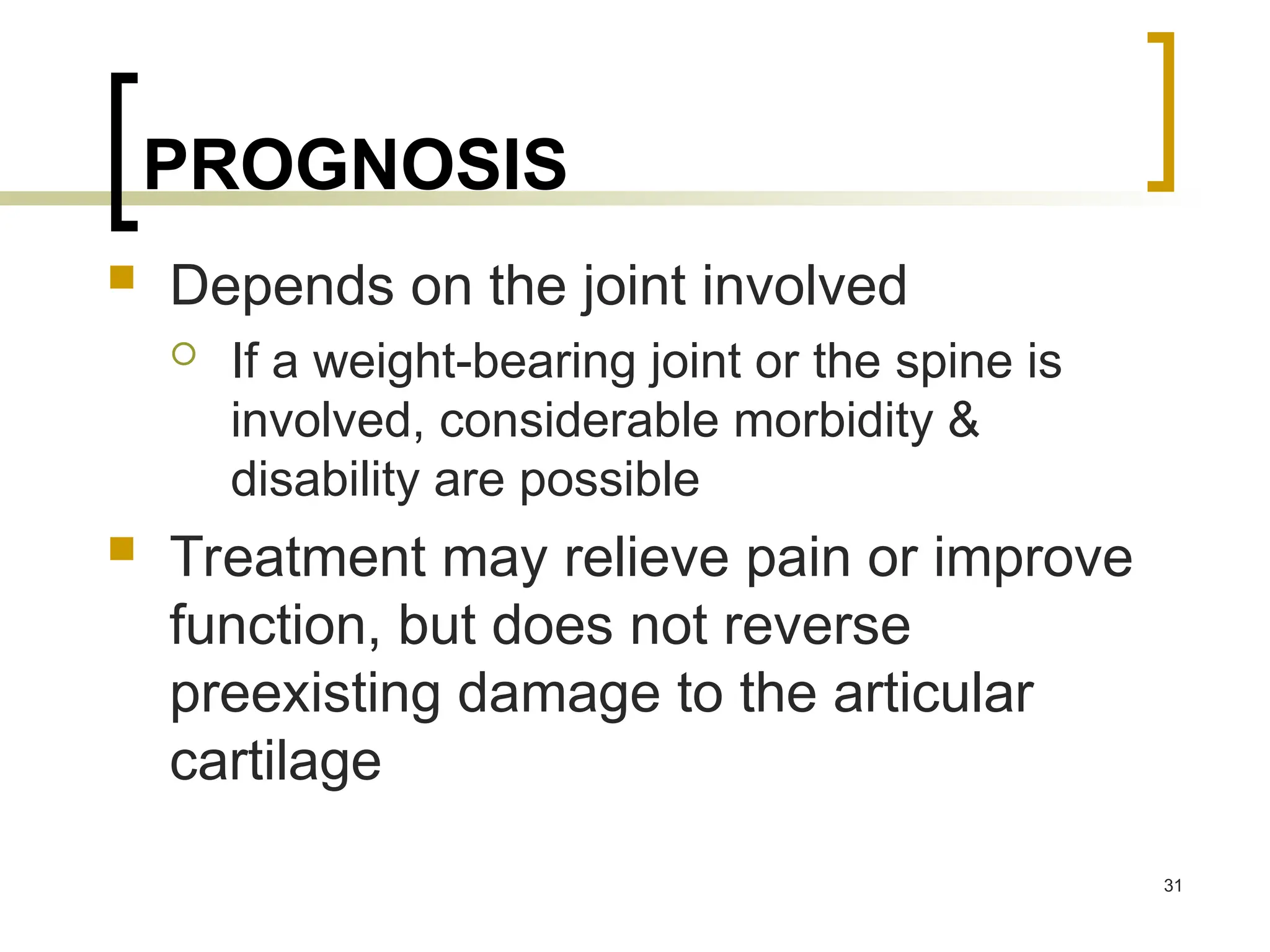

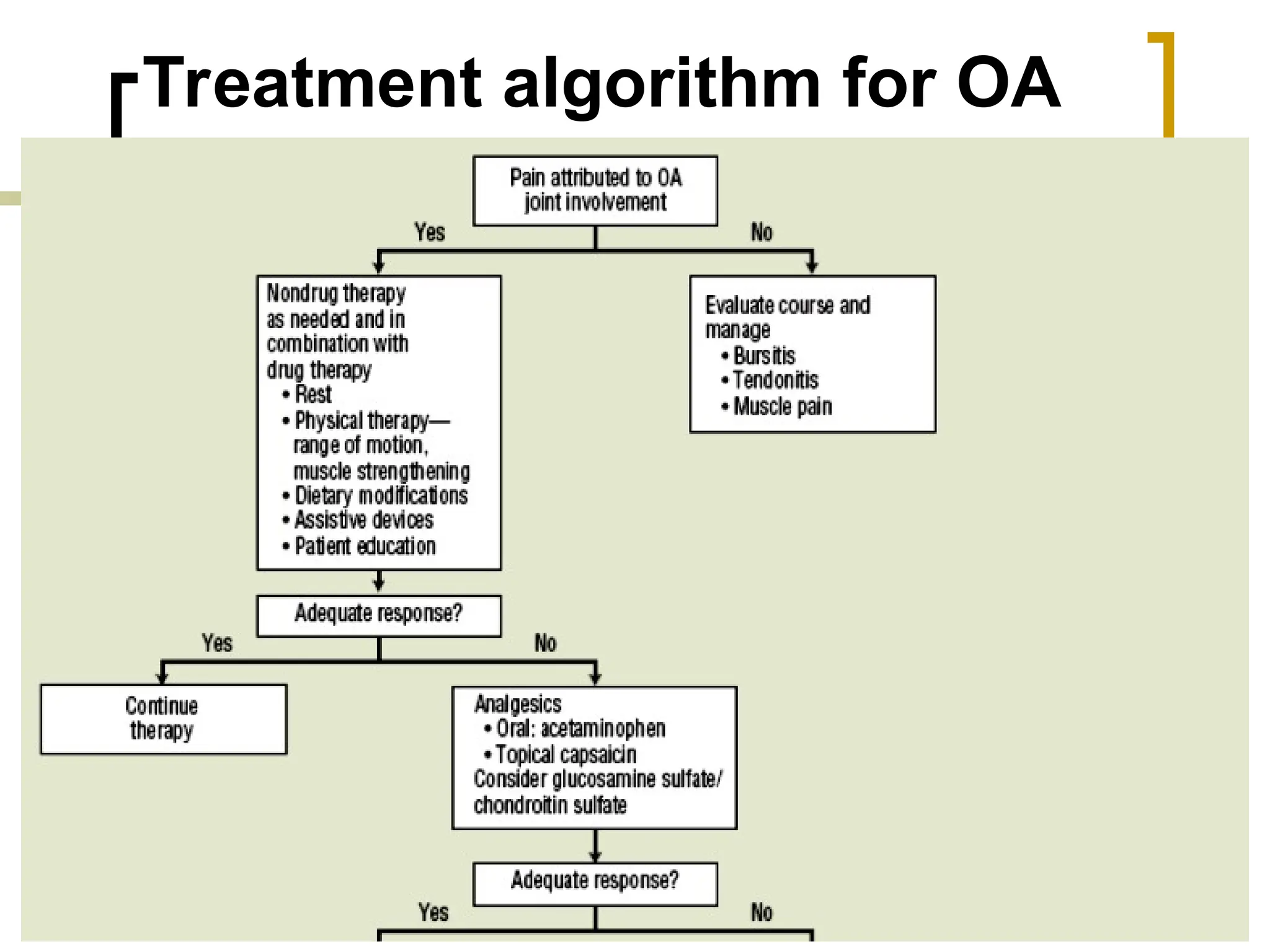

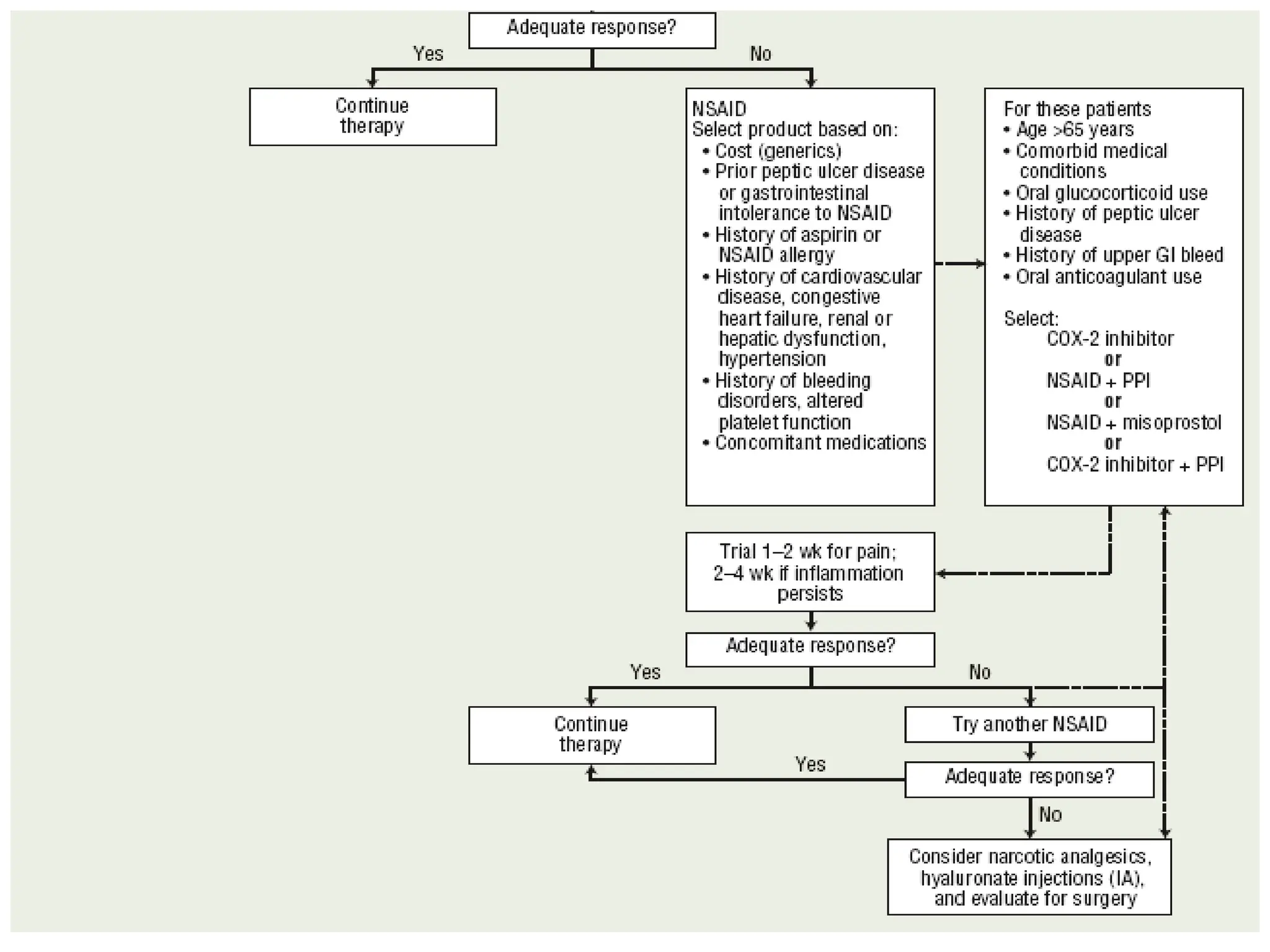

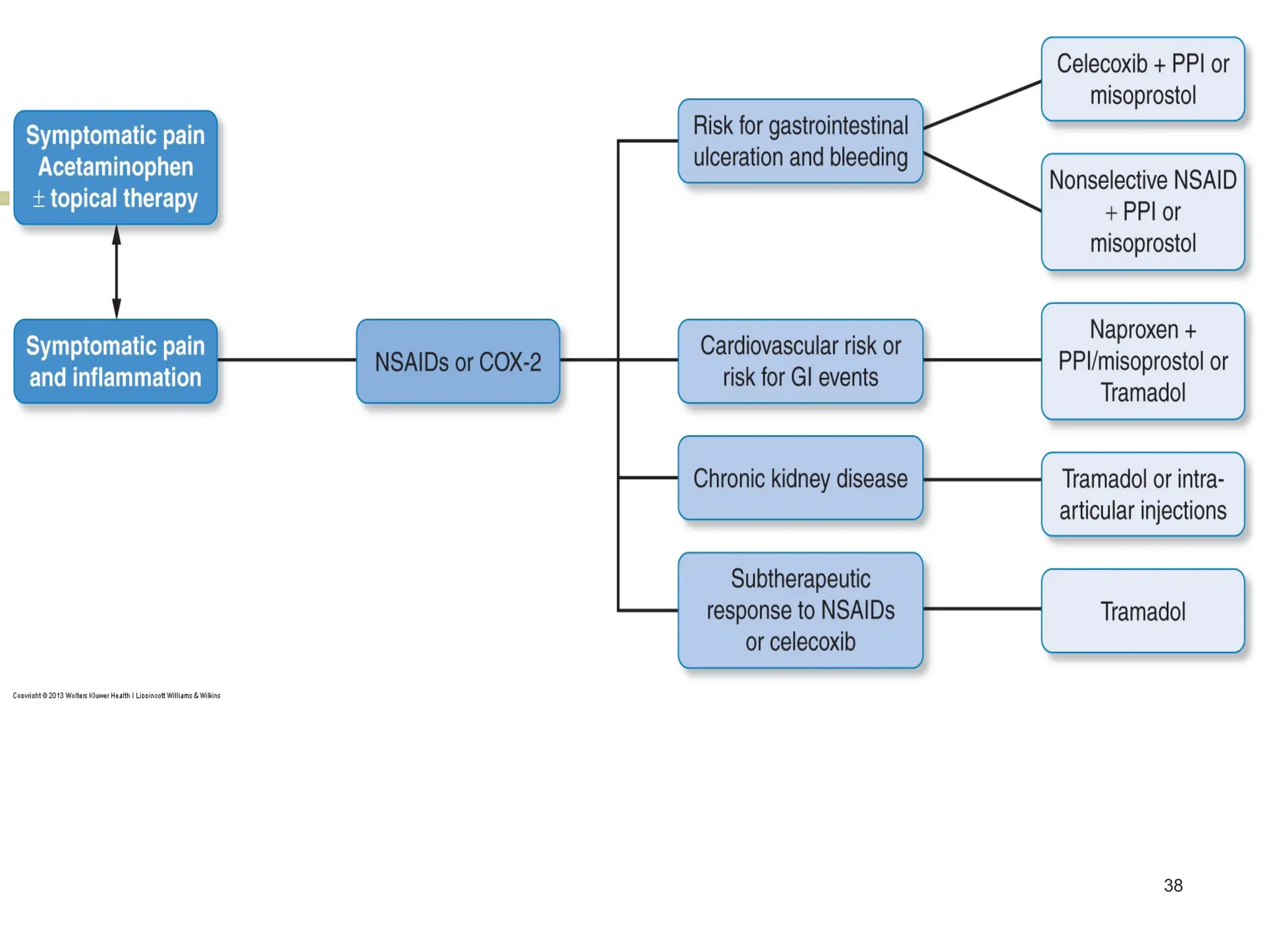

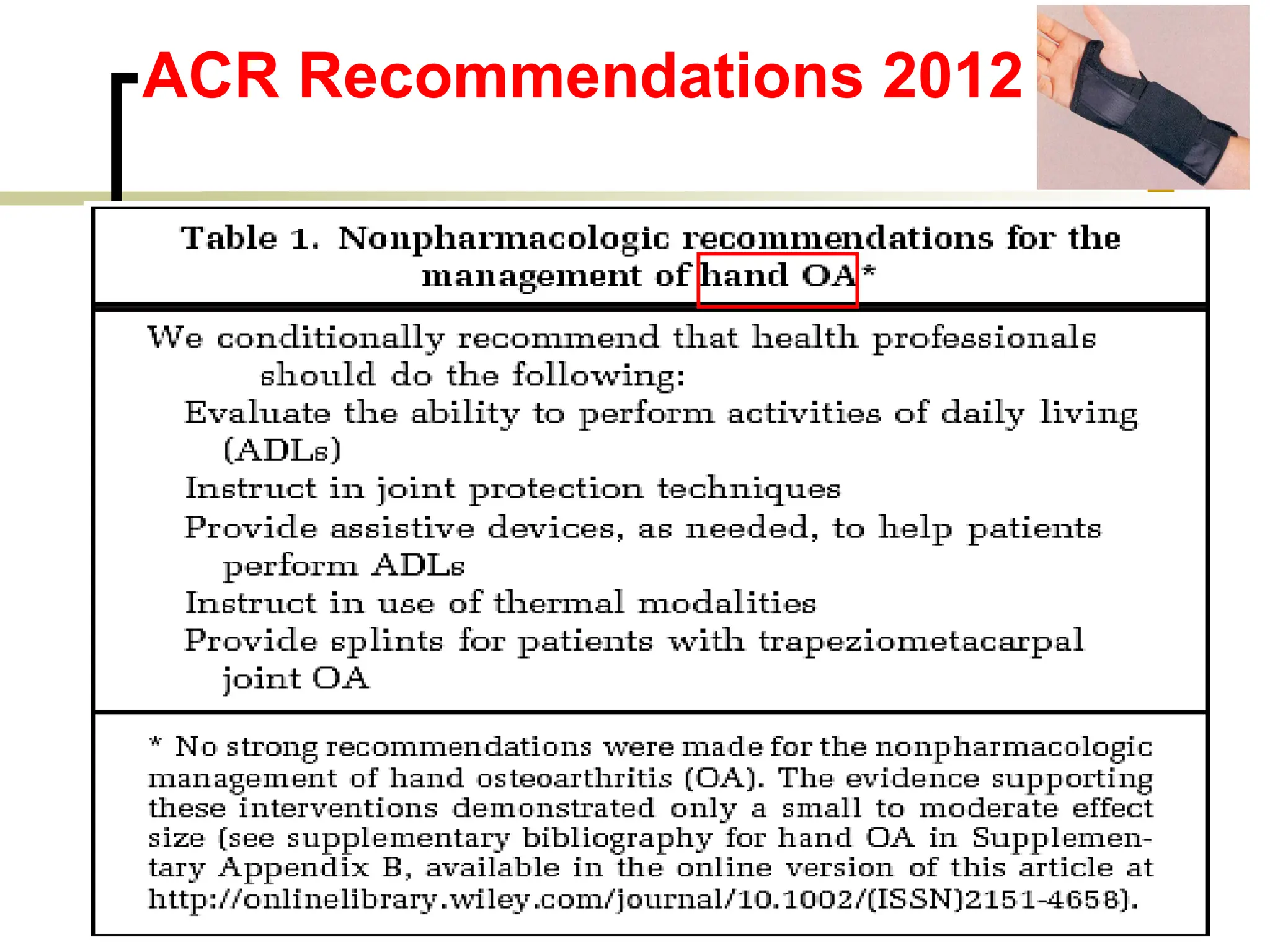

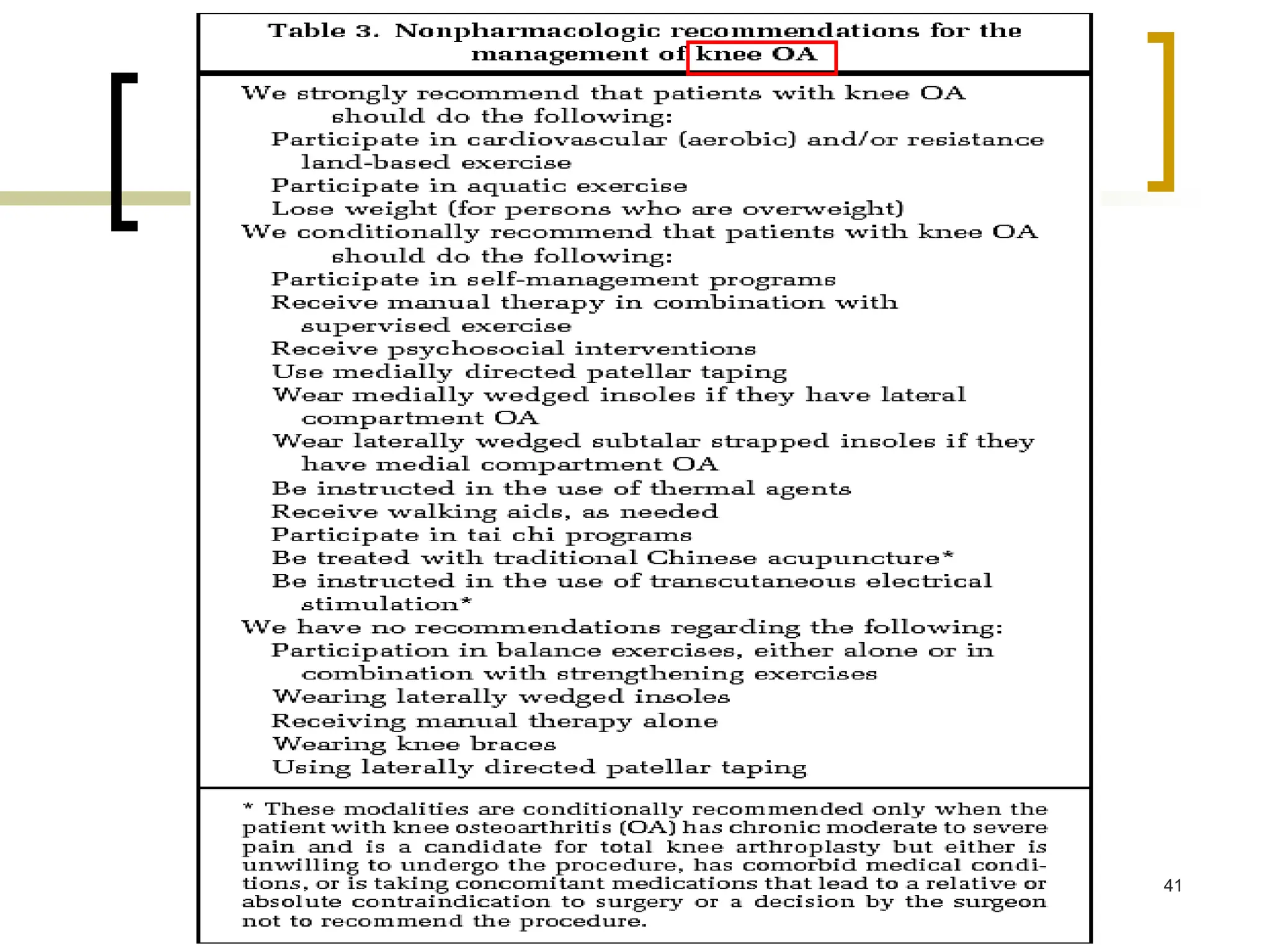

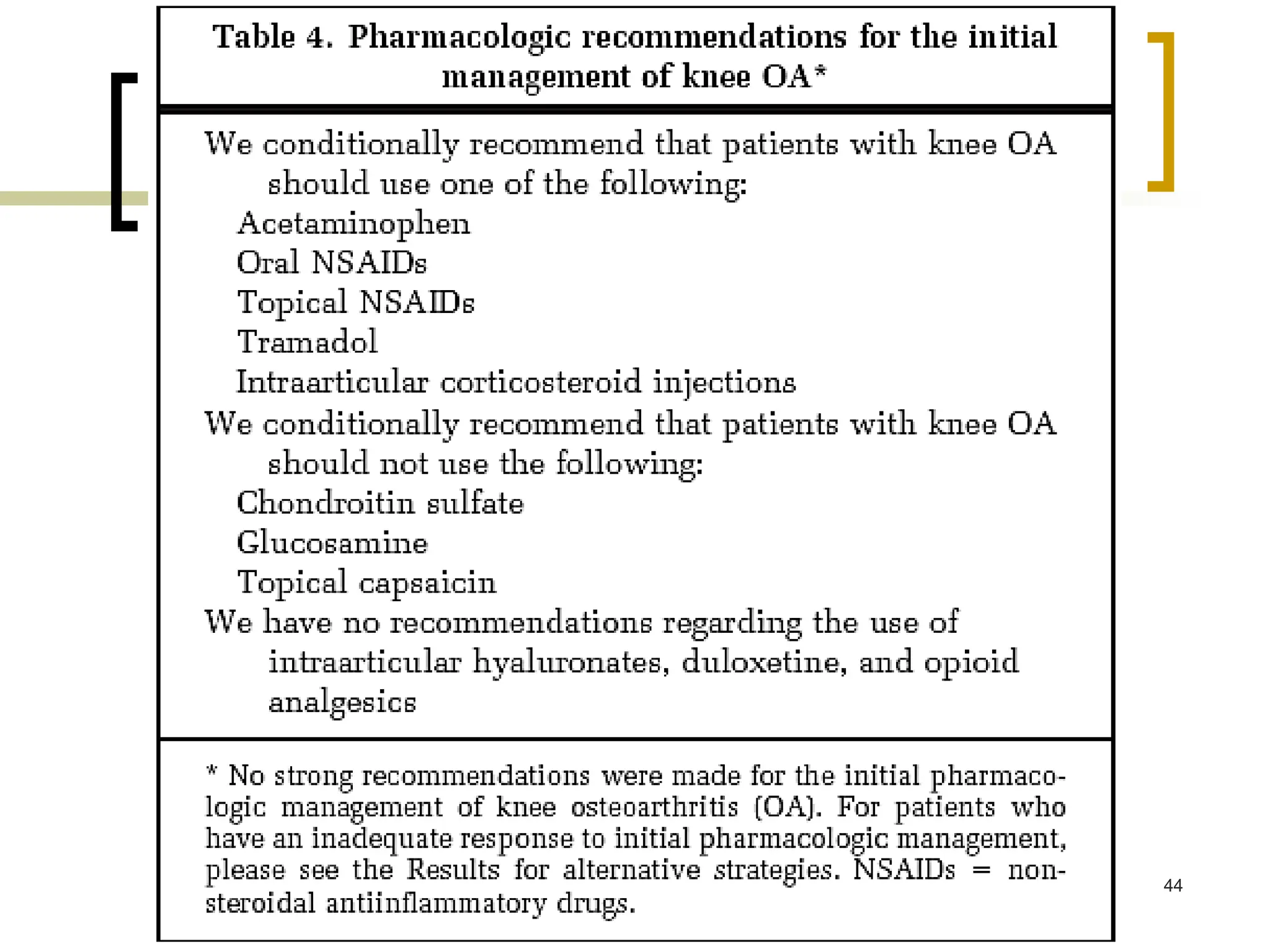

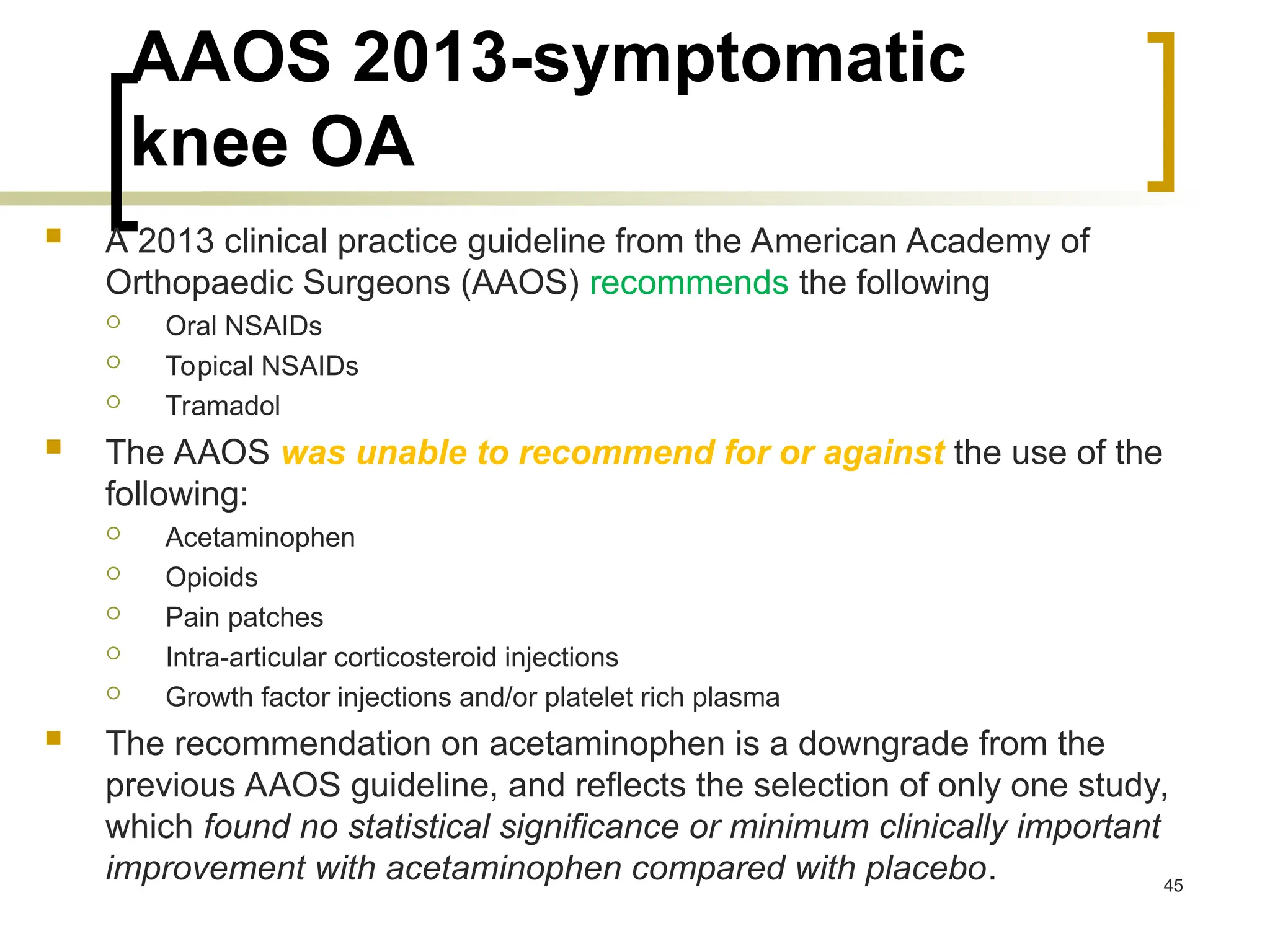

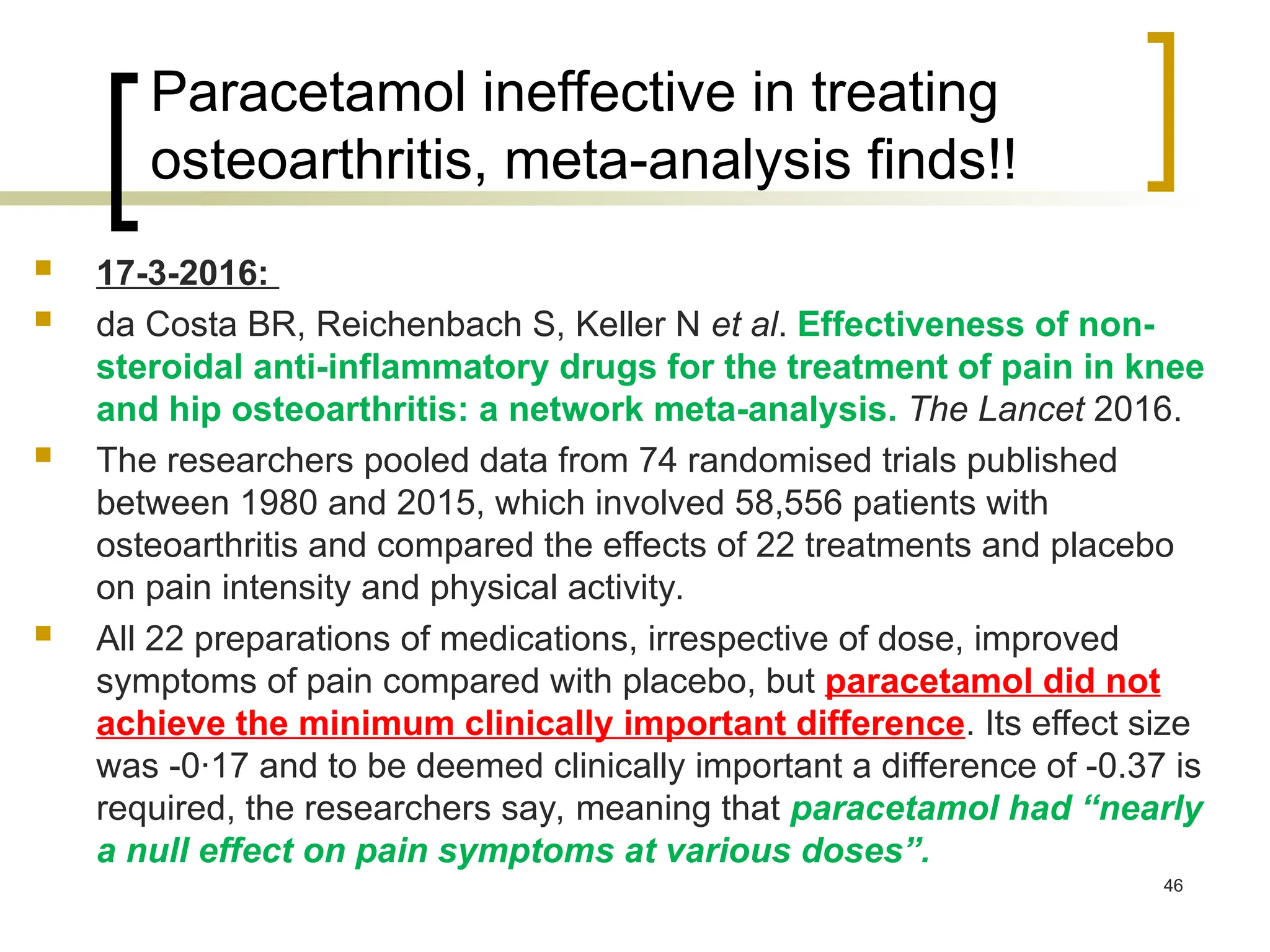

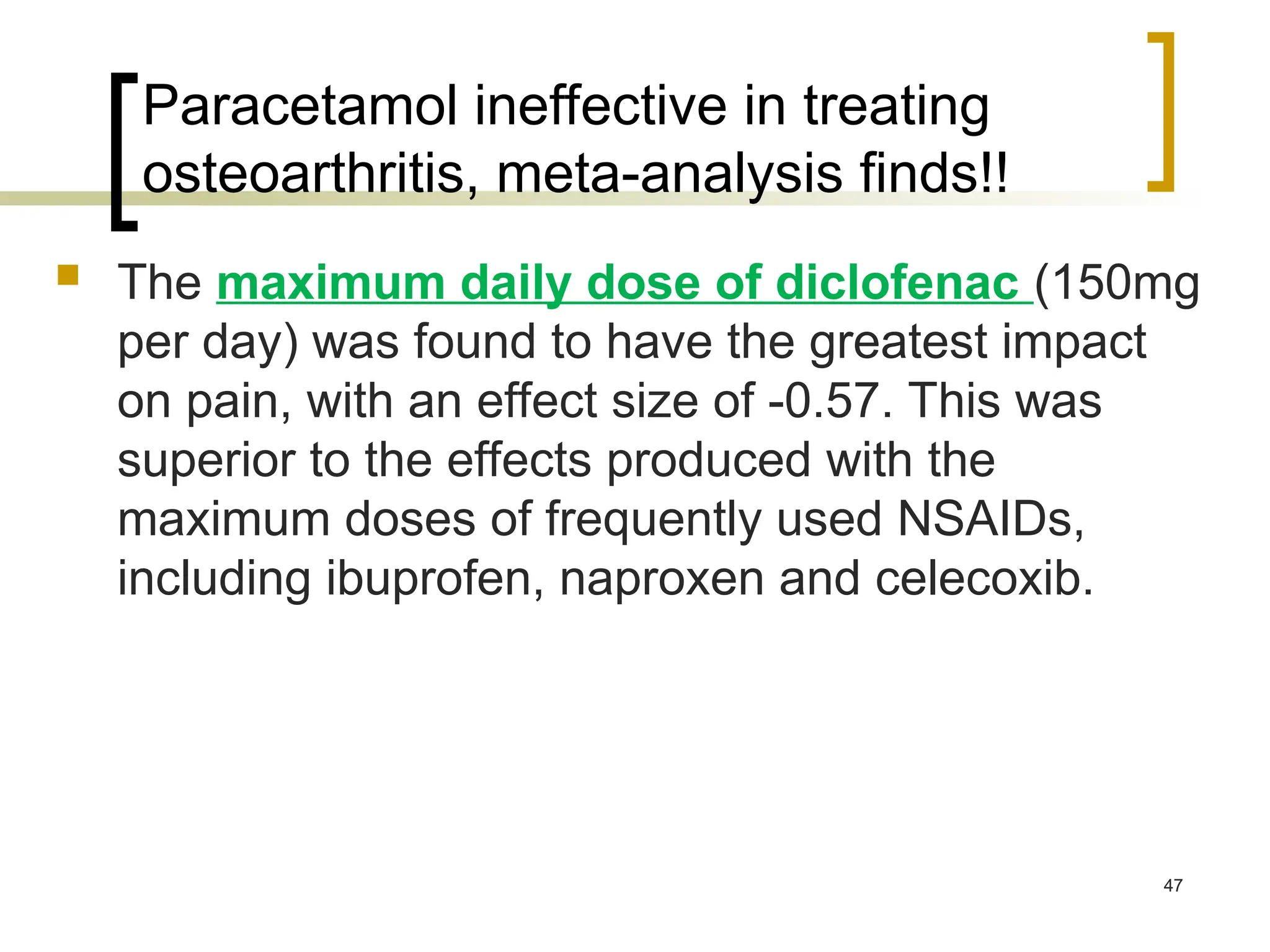

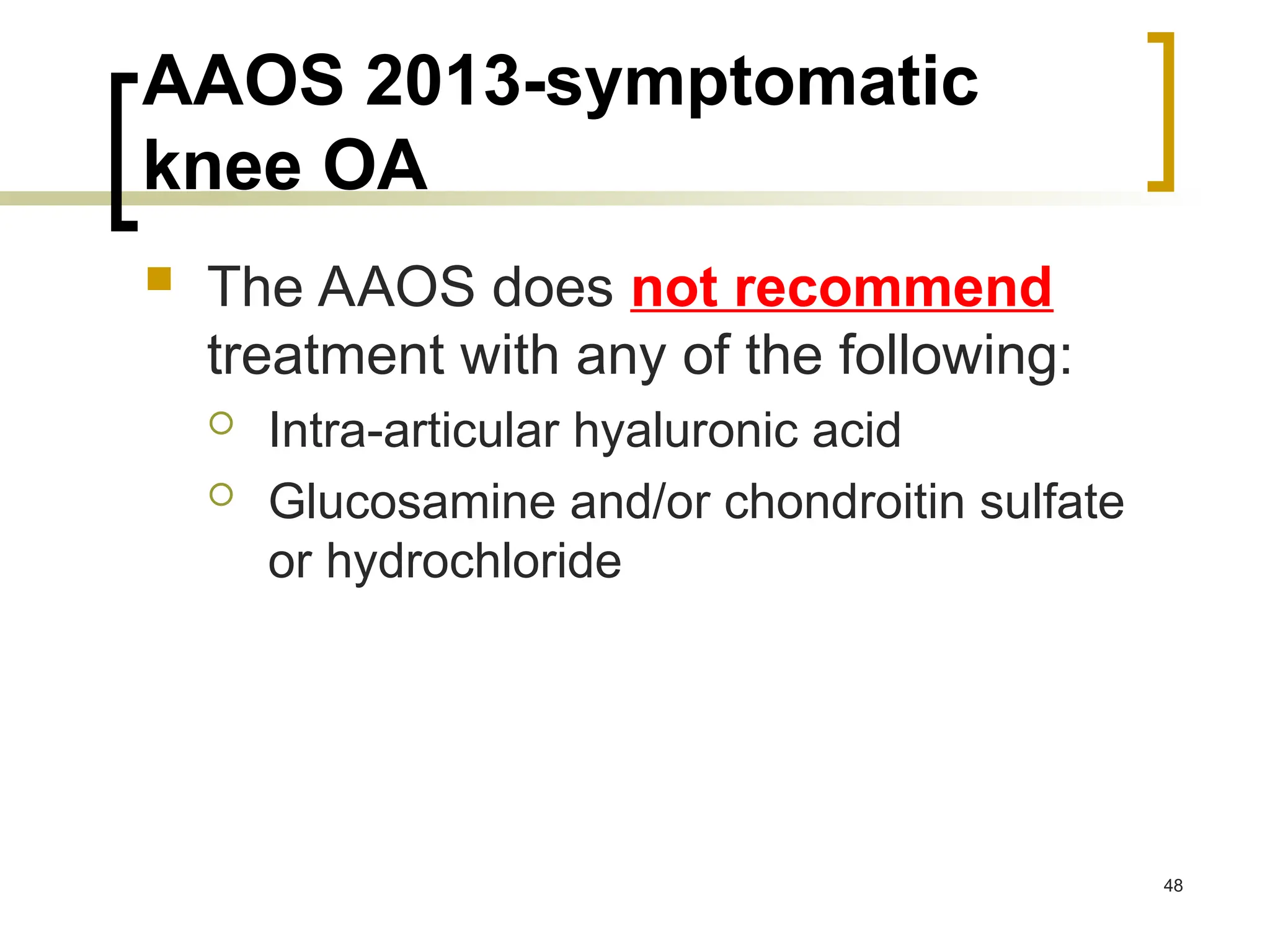

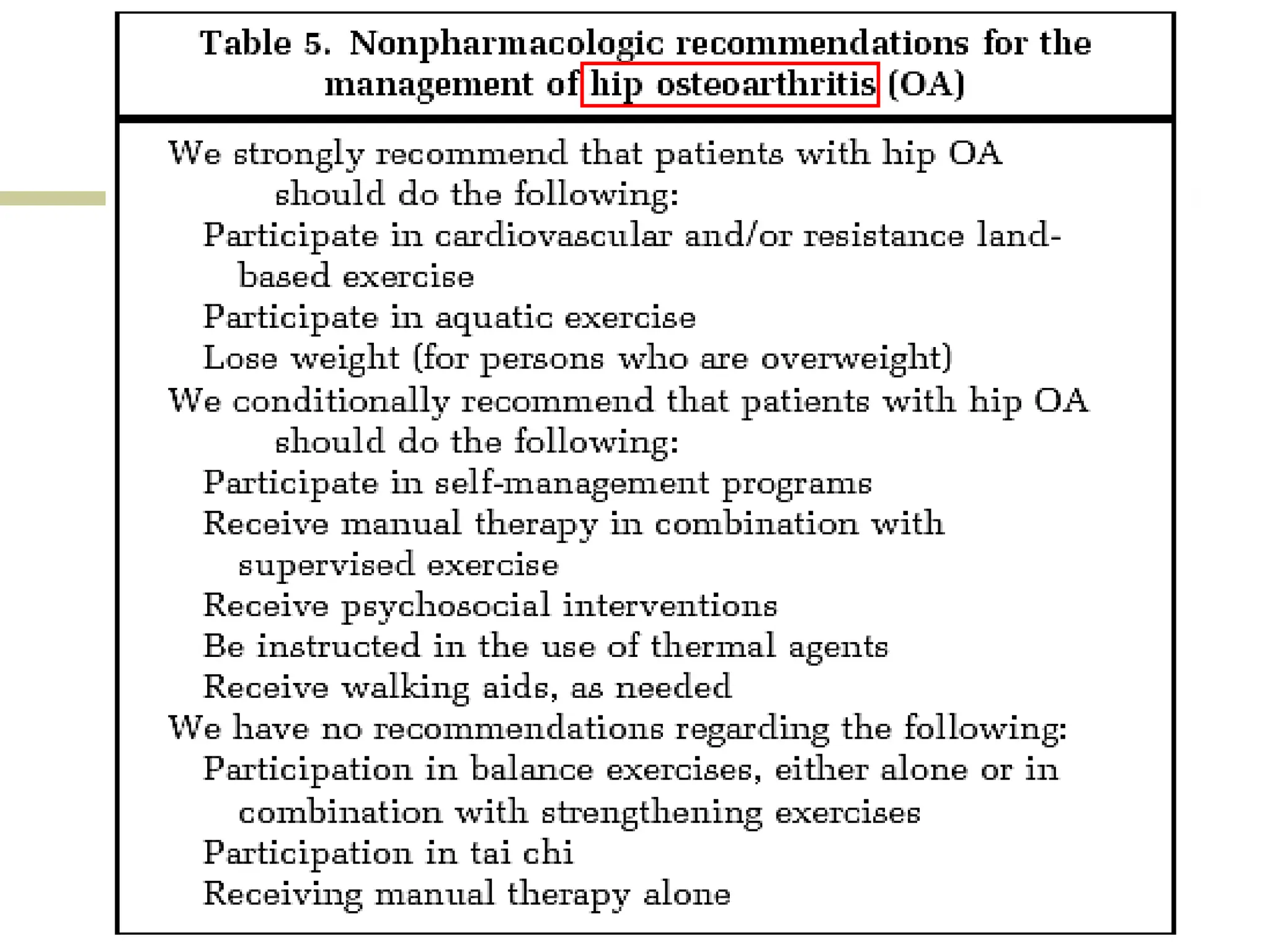

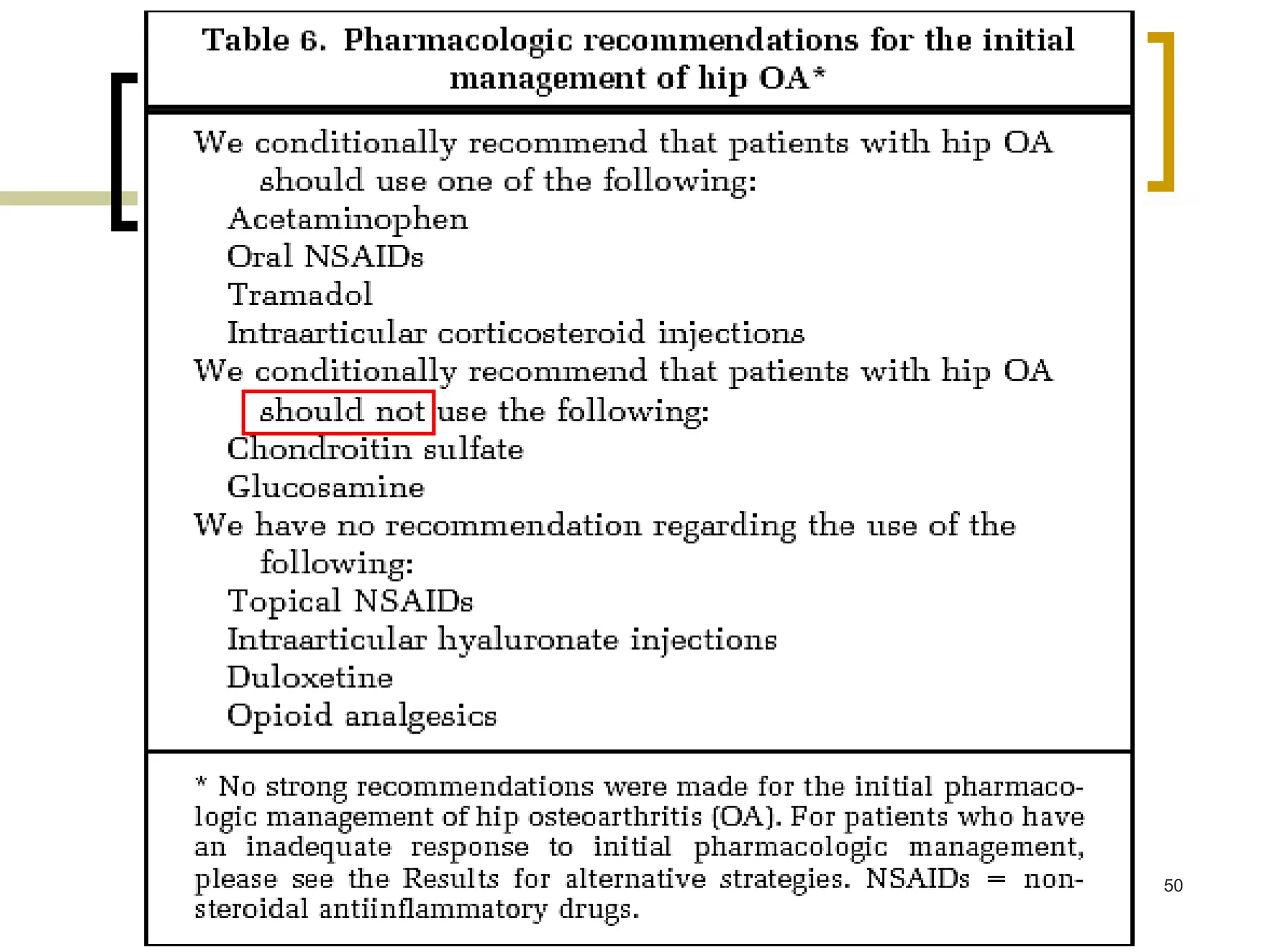

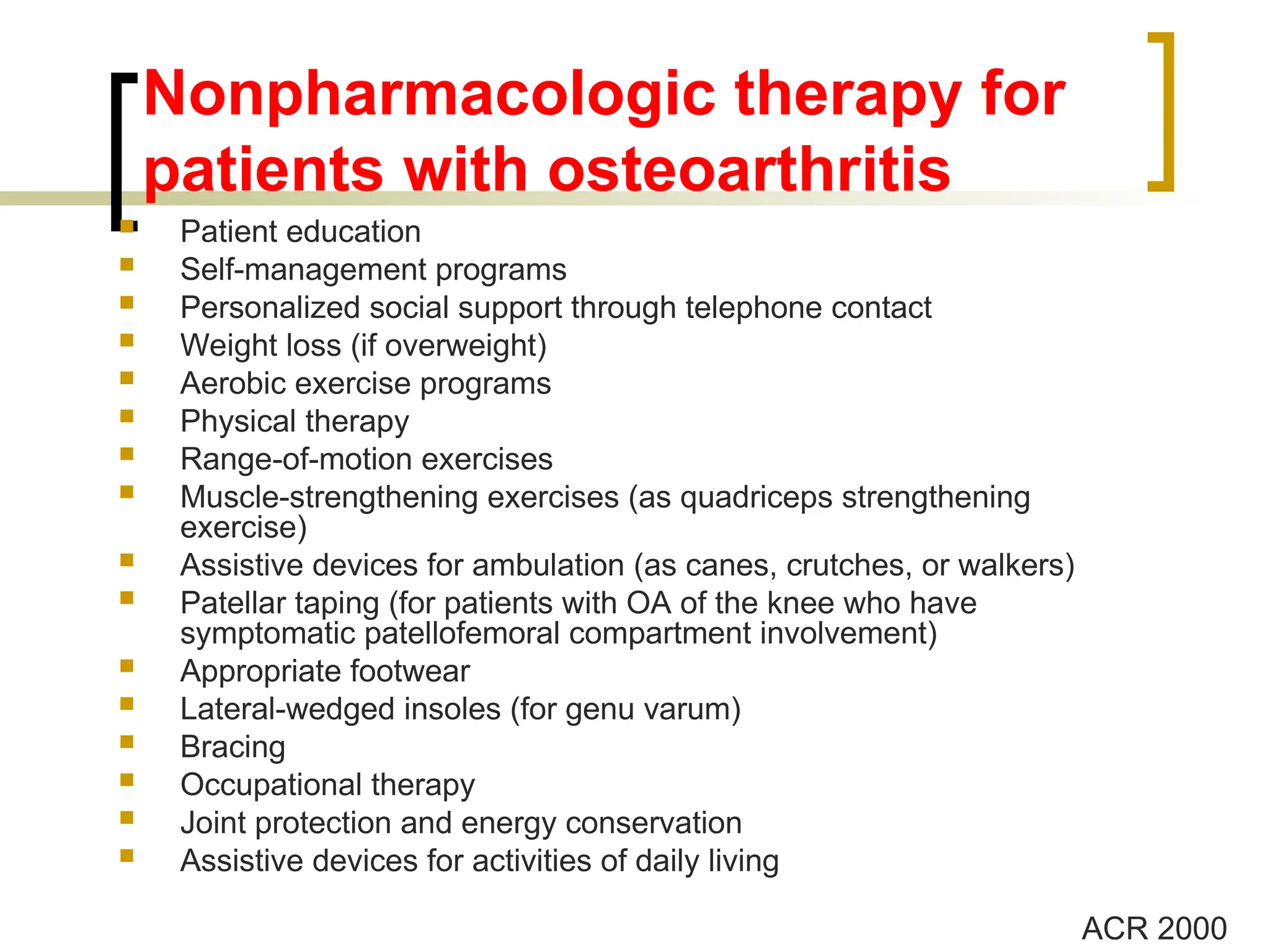

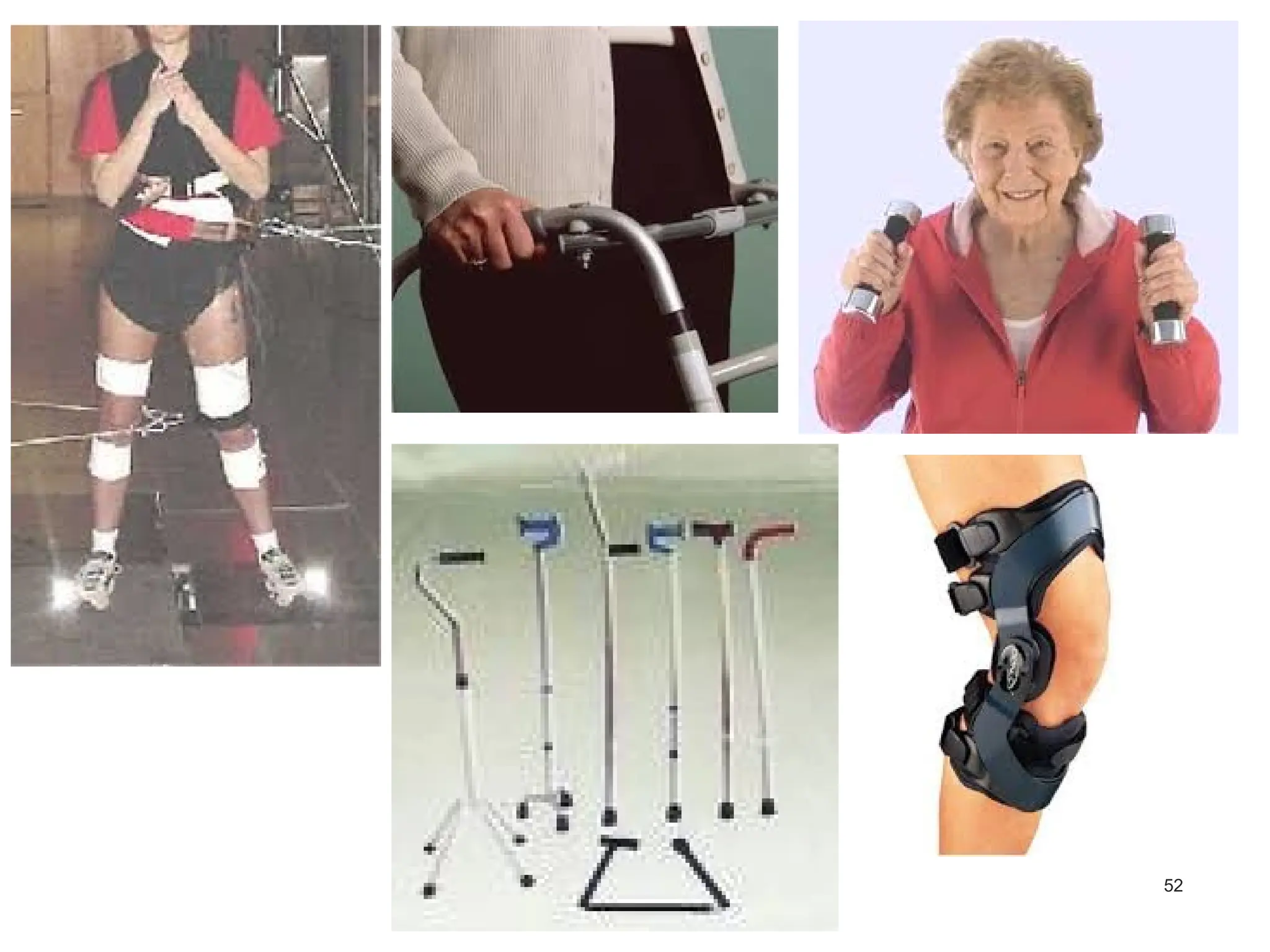

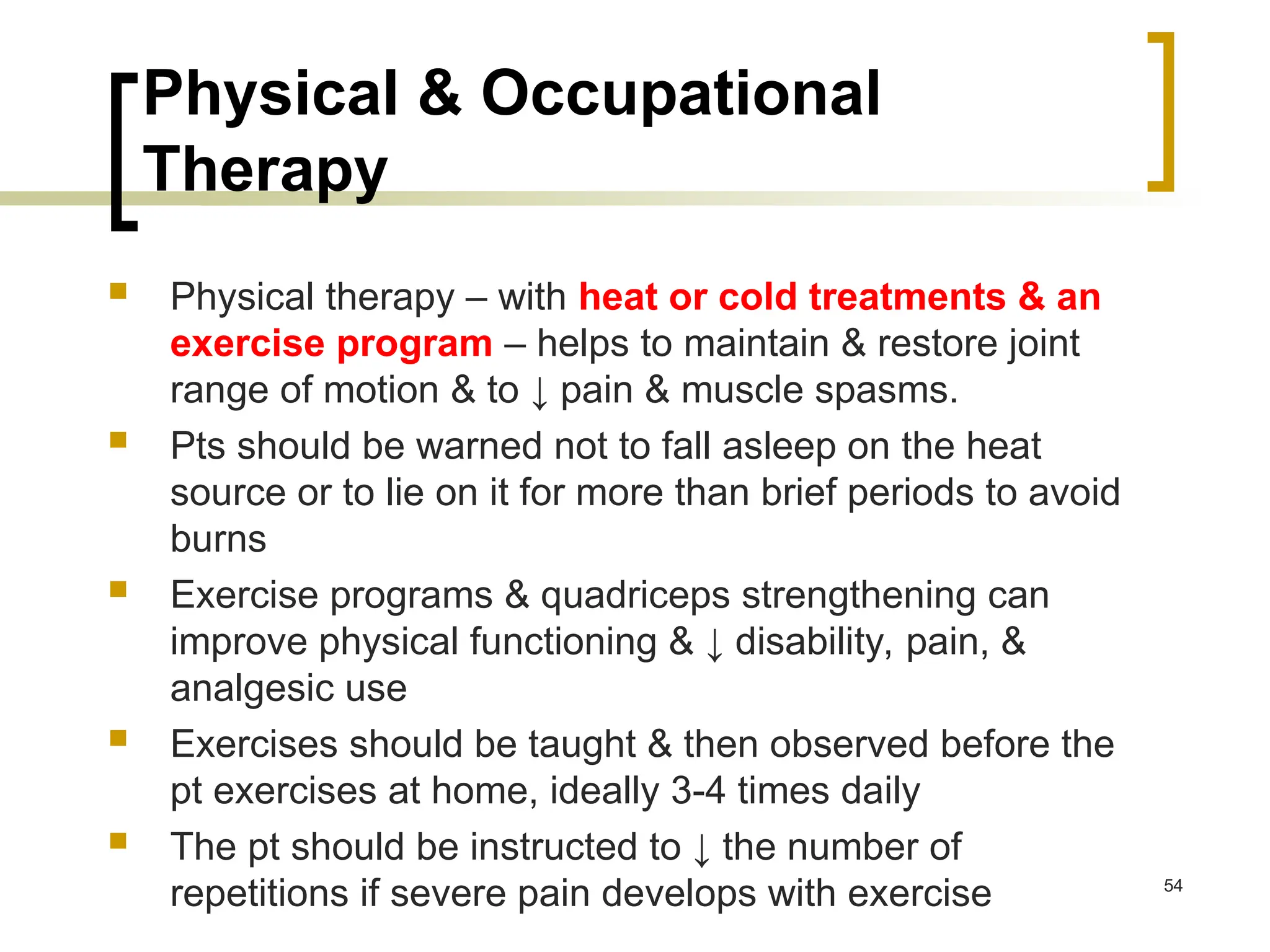

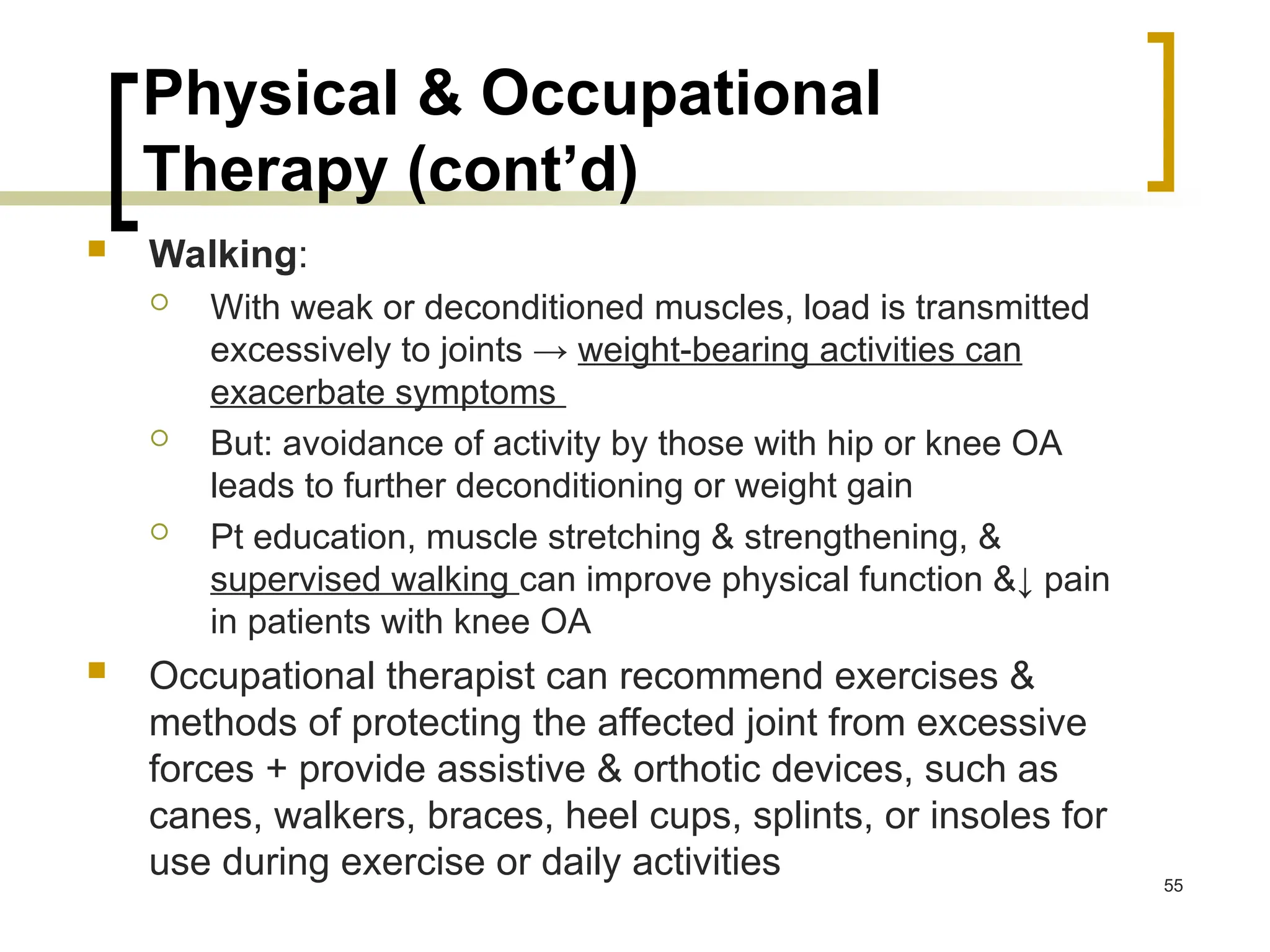

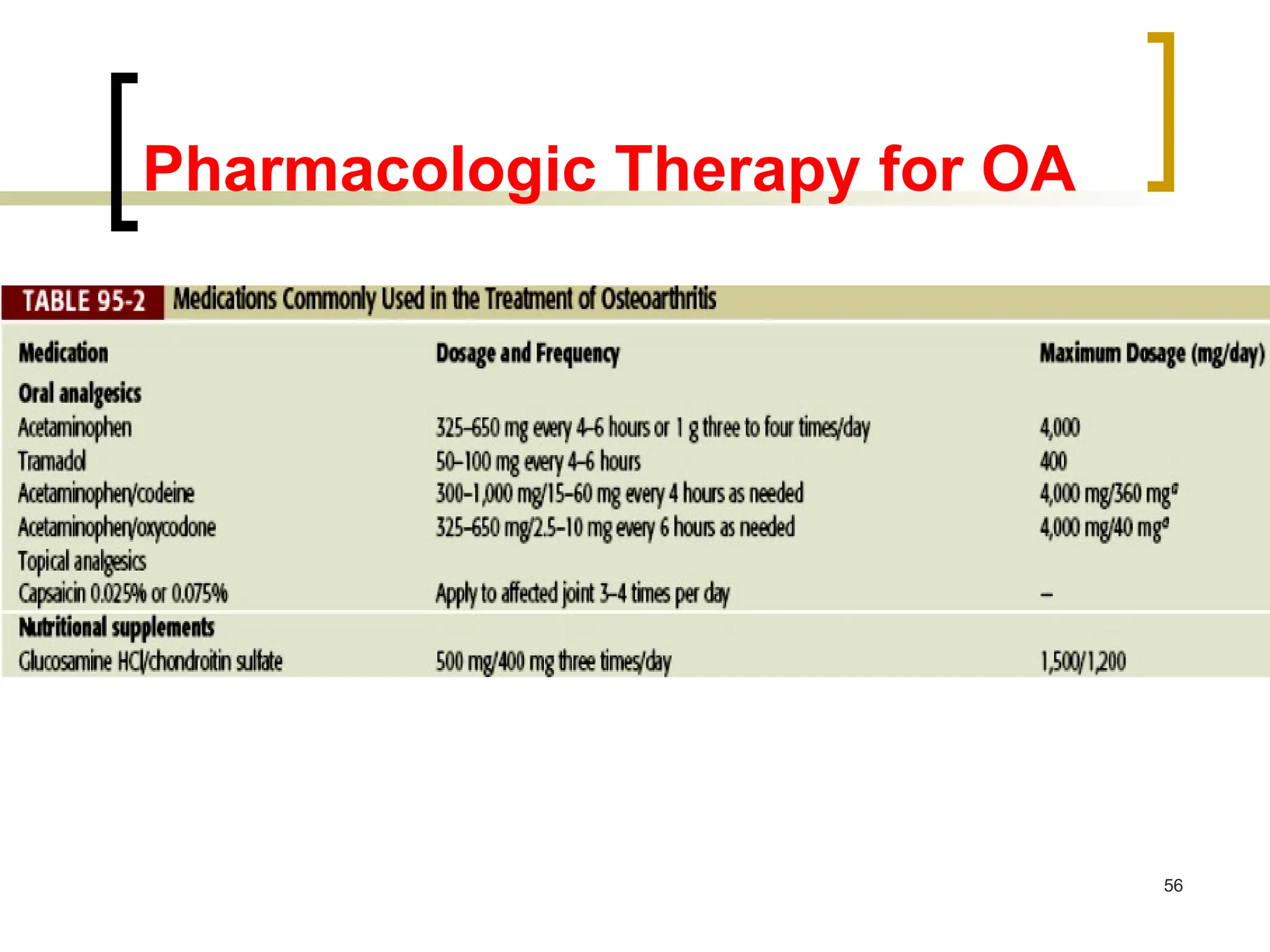

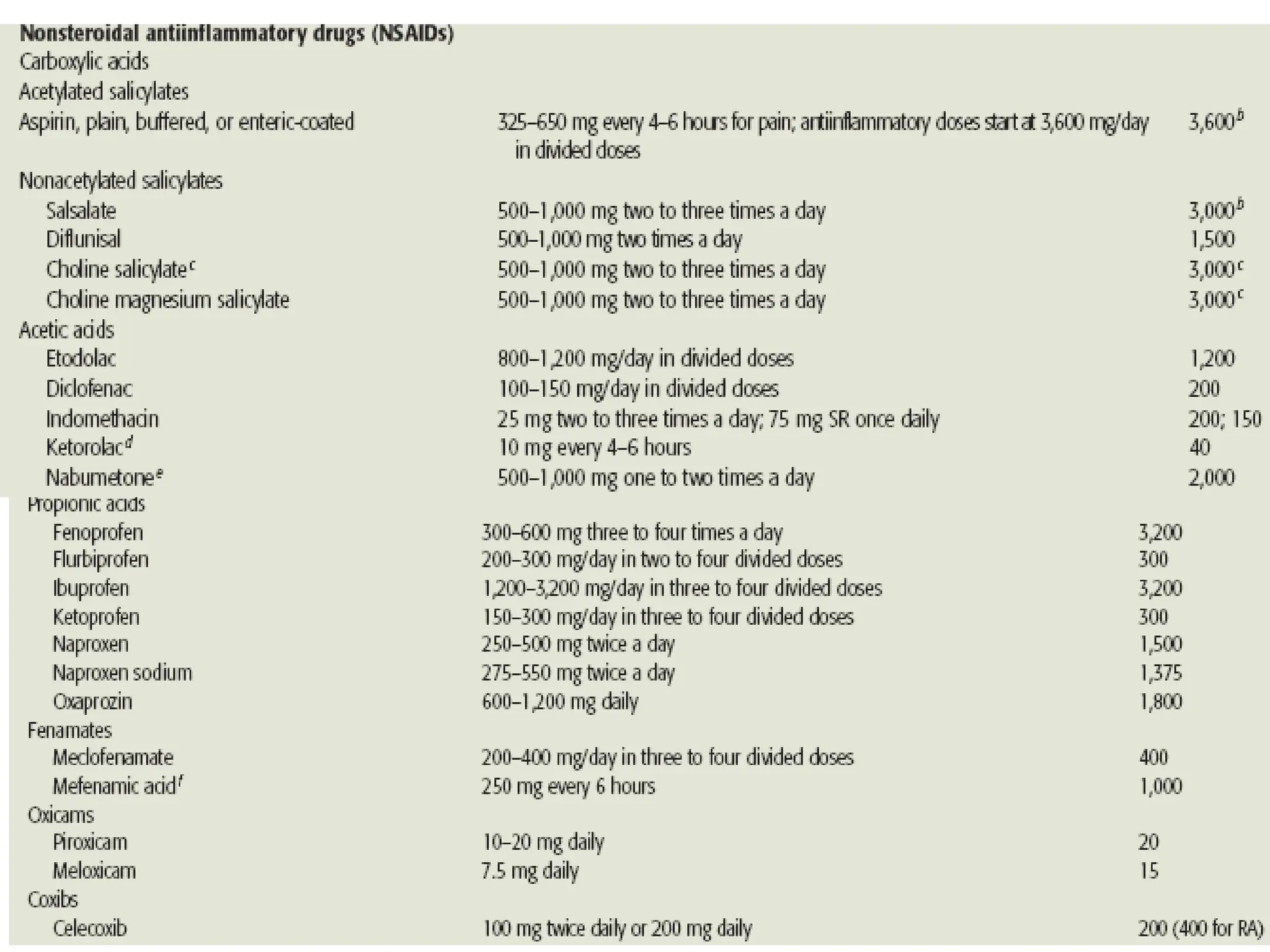

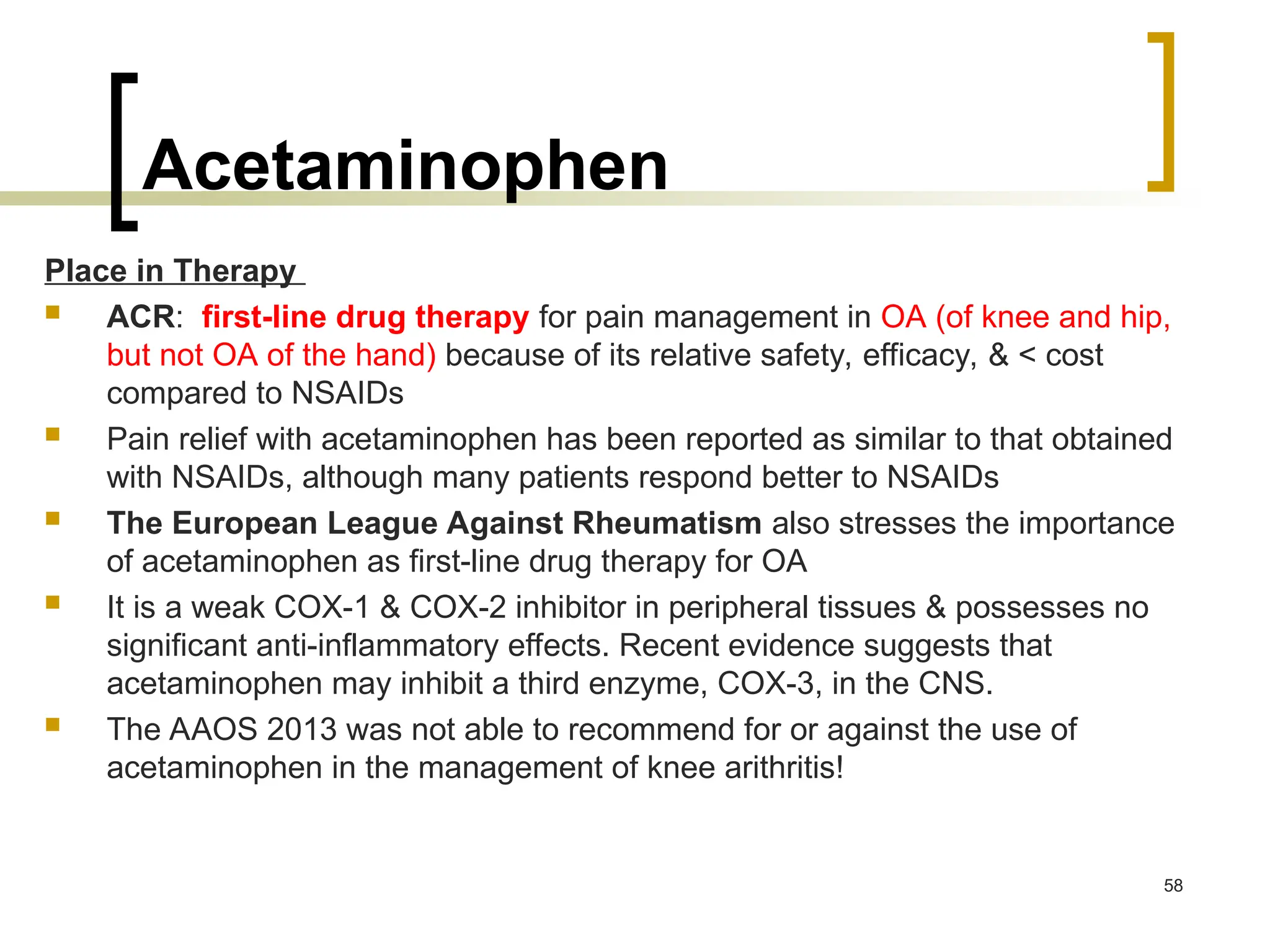

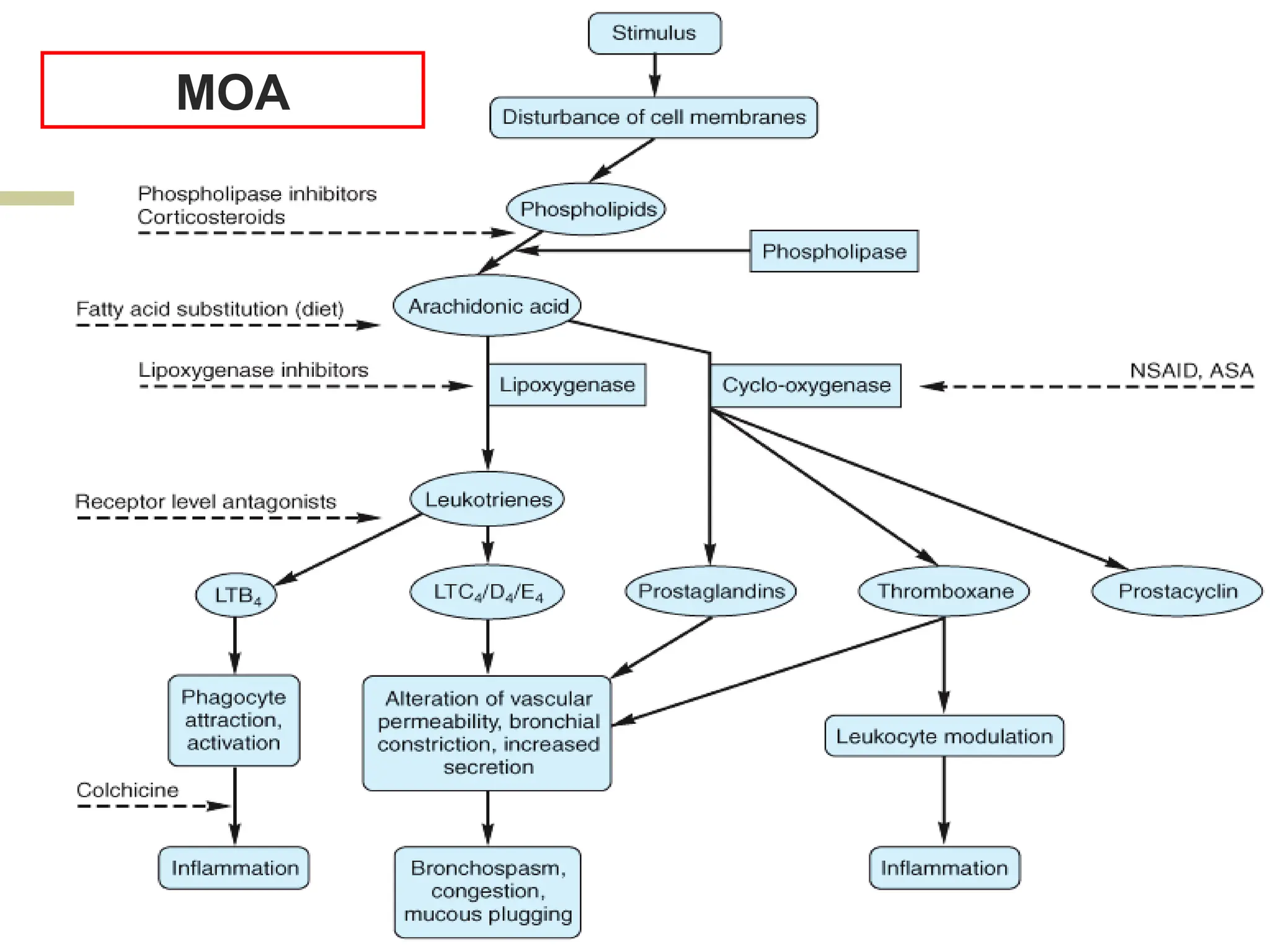

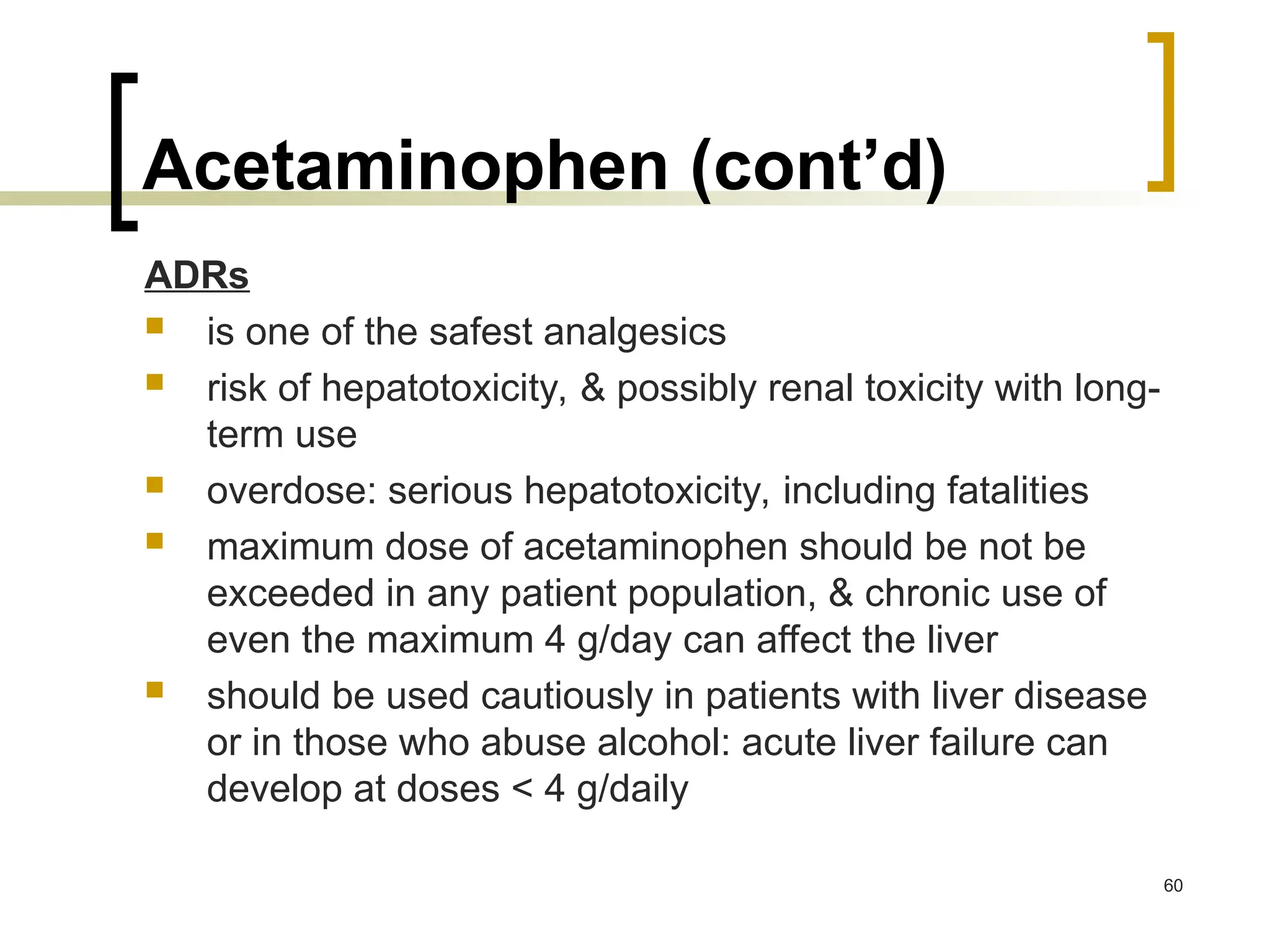

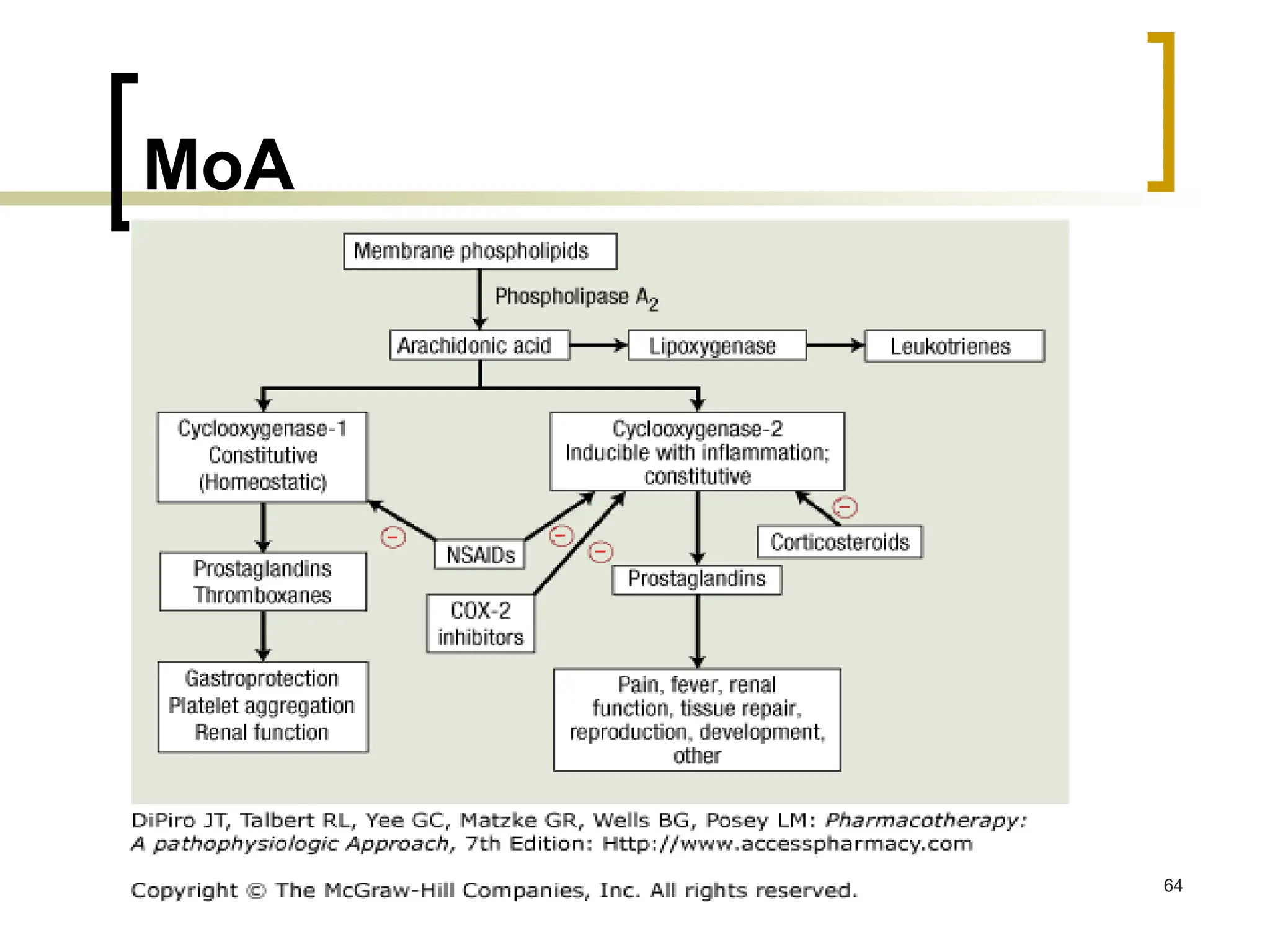

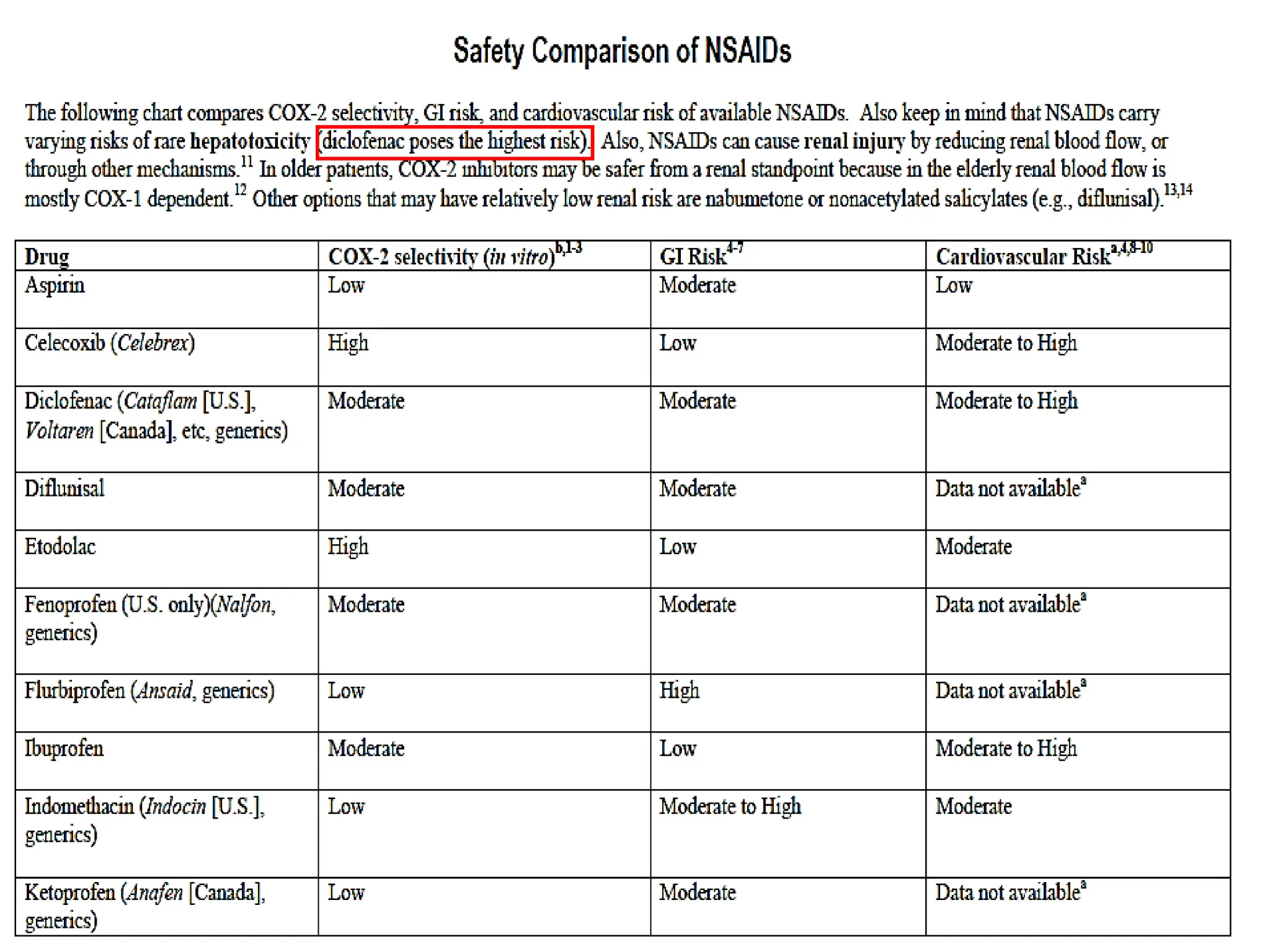

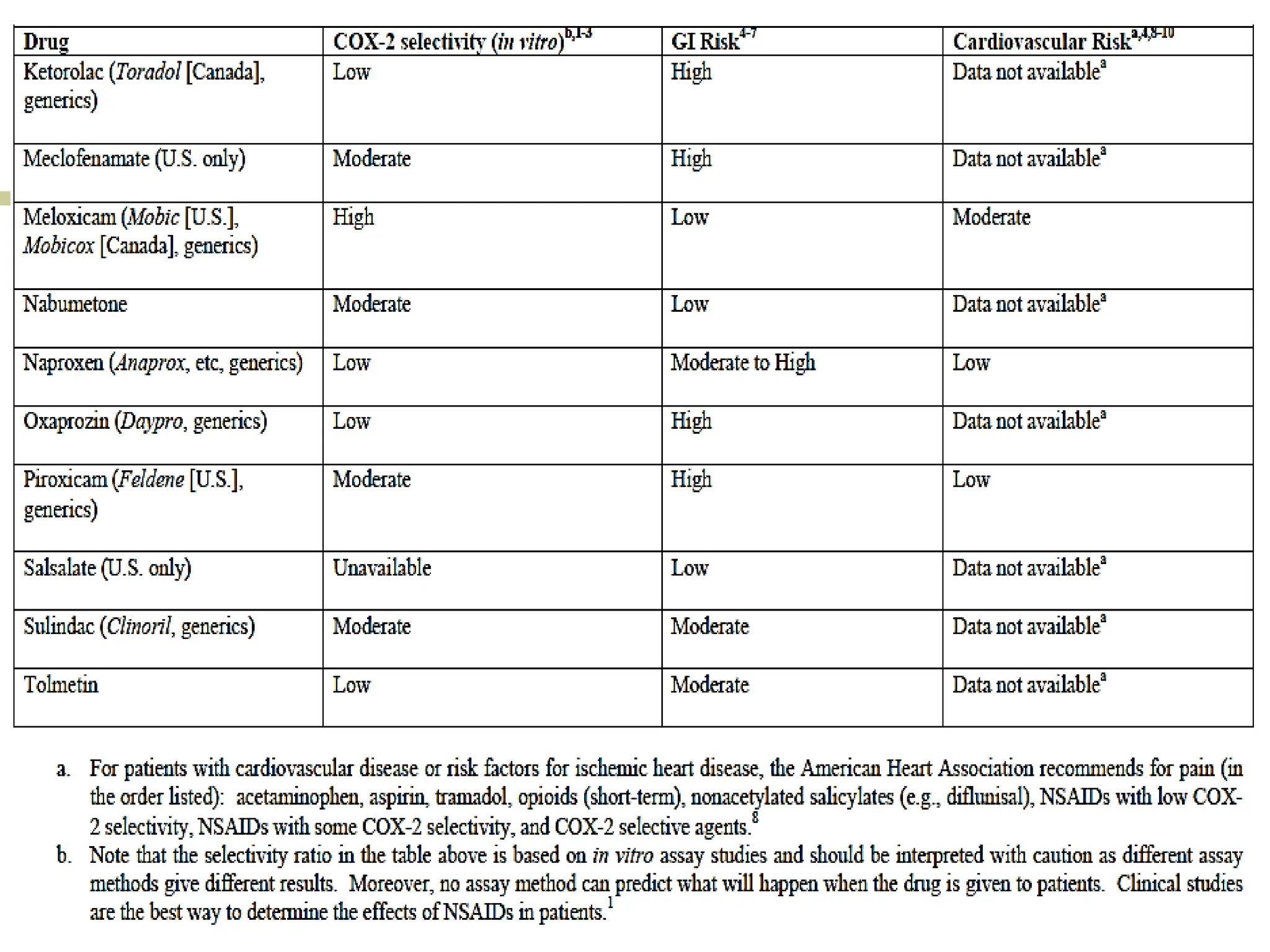

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a common degenerative joint disease characterized by cartilage degradation and bone overgrowth, leading to pain and stiffness, especially in the knees, hips, and hands. Although the exact causes are unknown, risk factors include aging, obesity, and previous joint injuries, with no cure currently available; management focuses on symptom relief through education, physical therapy, medications, and potentially joint replacement. Treatment recommendations suggest a combination of non-pharmacologic and pharmacologic approaches, with NSAIDs being commonly used for pain relief.

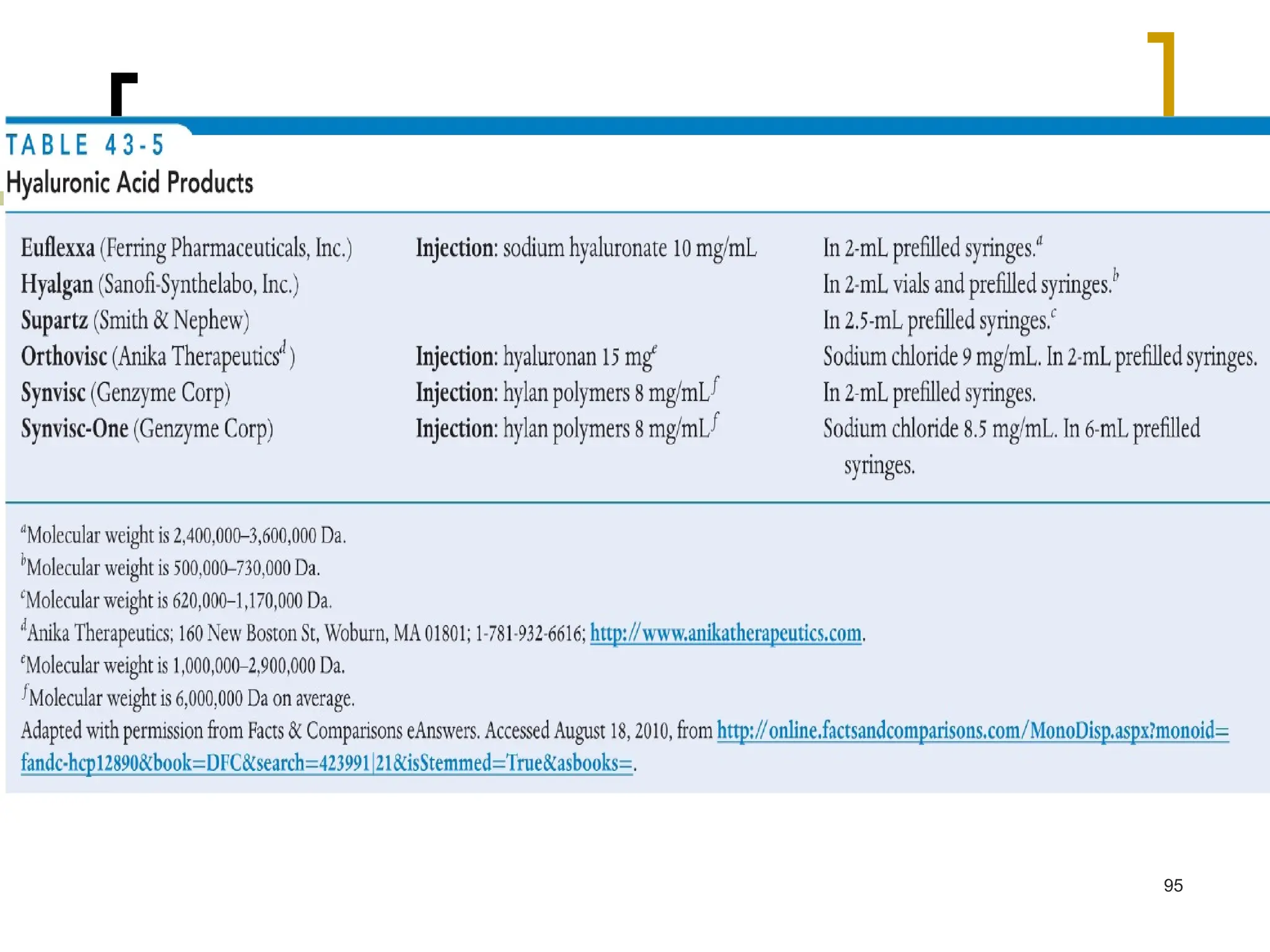

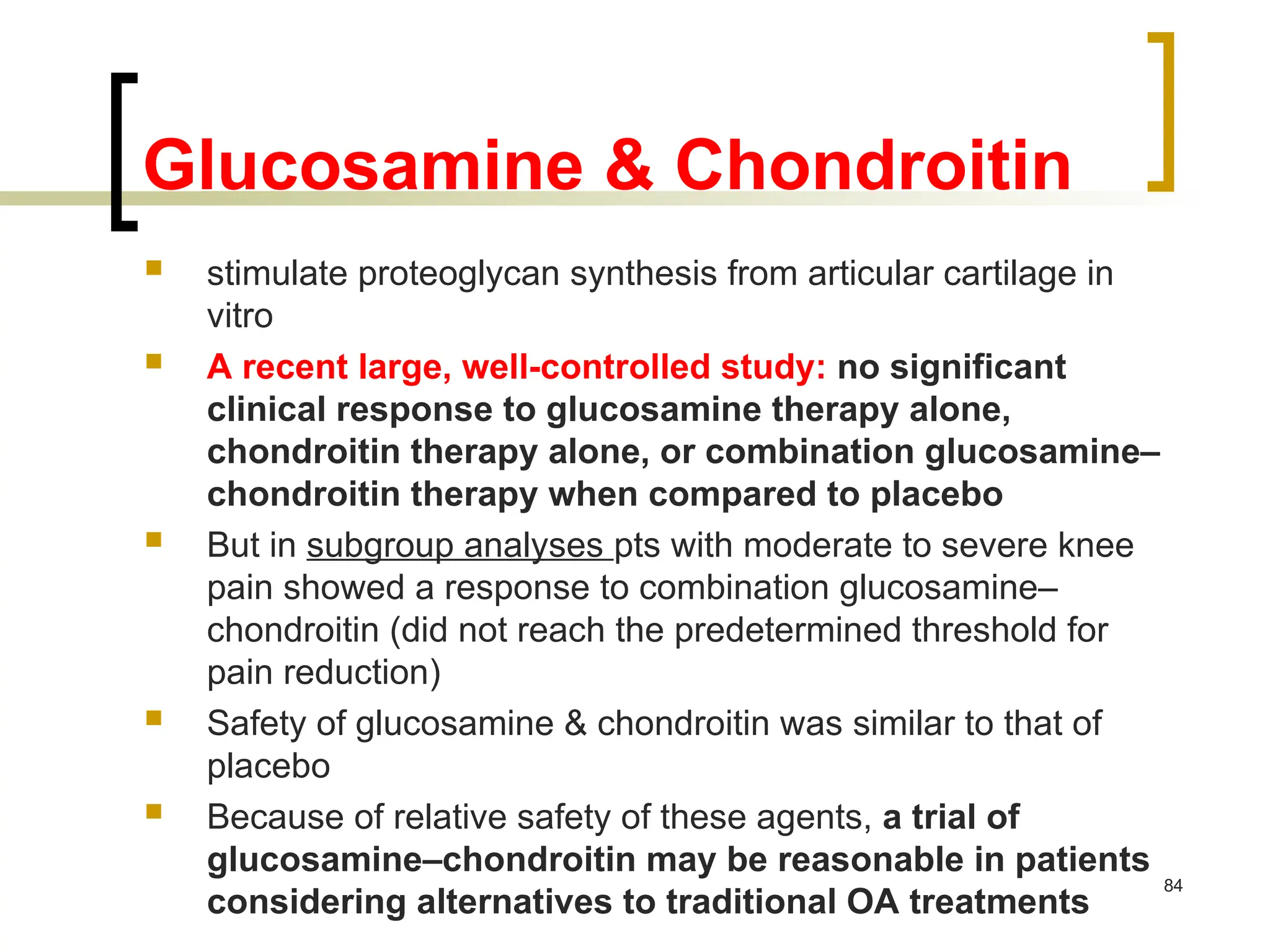

![NICE 2014 Update

Do not offer intra-articular hyaluronan

injections for the management of

osteoarthritis. [2014]

Efficacy is modest and inconsistent.

Prices of hyaluronan injections are

expensive.

94](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/6-osteoarthritis2017final-241019000400-2c281296/75/Topic-3-Osteoarthritis_2017_finalize-ppt-92-2048.jpg)